|

|

|

|

He's convinced that the ocean

was only a barrier to man as long as our ancestors were strictly

pedestrians, but it became a conveyor for cultural contact and

the growth of diversified civilizations from the moment the first

sea-going watercraft was invented. Heyerdahl accepts the "isolationist"

claim that cultural parallels are often due to the analogies

of man's need and nature, but he holds a "diffusionist"

view when it comes to explaining the concentrated clusters of

cultural identities and analogies which suddenly emerged in coastal

areas of the Old and the New World as shipbuilding spread from

the Middle East some five thousand years ago.

The question for Heyerdahl has simply become: "Where and

when did the 'zero hour' of civilized man begin?" (See Thor

Heyerdahl's article in this issue -"The Azerbaijan Connection"

in which he makes public for the first time, his "growing

suspicion" that the region of Azerbaijan may be one of the

important early dispersion centers.)

|

|

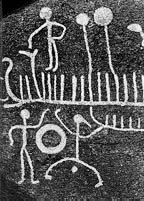

Above: Left:

Boat petroglyphs on rune

stone (Copenhagen National Museum). From Larousse World Mythology,

1965.

Above: Right:

Cane boat petroglyphs near

Fredrikstad, Norway. Photo: Jacqueline Beer.

Sails before Saddles

Heyerdahl is fond of

saying that "man hoisted sail before he saddled a horse.

He poled and paddled among rivers and navigated open seas before

he traveled on wheels along roads." Like a detective in

search of missing clues, Heyerdahl believes the search for mankind's

first vehicles - water craft - will take him back to the source

of civilization.

"I believe I've opened the locked door to the hidden evidence

that the vessels of antiquity permitted unrestricted voyages

in pre-European times and that there is a complex global root

relationship between all those rapidly growing civilizations

that suddenly grew up with evidence of advanced boat building

some 5,000 years ago."

Evidence for this comes from Heyerdahl's expeditions which all

were based on authentic boat designs, either found on petroglyphs,

etched or painted on ancient walls, burial crypts, ancient seals,

or from the memories of people who still use such craft.

Looking back, one would have hardly found the young Thor a likely

candidate for a career that would make him so vulnerable to the

world's largest bodies of water. Before "Kon-Tiki"

he had never sailed a boat, much less a raft. As a child he had

almost drowned in an accident.

Even now when Heyerdahl looks back on the oceanic voyages, he'll

admit, "There were moments during every one of my experimental

voyages that I was momentarily deadly afraid. Like seafarers

throughout the ages in similar situations, I felt I survived

through my faith in some superior invisible power. Gradually,

I got used to the friendly partnership between the dancing ocean

and its gentle playmate, our flexible, wash-through aboriginal

raft-ships. Of course, my closest friends worried about me, but

they knew I loved life and assumed I had founded my unshakable

faith in my scientific theories on solid facts."

Reed Boats Only

Look Fragile

Heyerdahl admits that

a single reed of papyrus seems so fragile that you could hardly

dare think about entrusting it with your life on a violent ocean.

But when reeds are harvested in the appropriate season and tied

together in bundles, he found they made a boat that was exceptionally

seaworthy, virtually unsinkable and safer than any canoe or ship

with a vulnerable hull. When breakers surge over a reed boat,

all the water which showered onboard disappears the same instant

through a thousand fissures.

Heyerdahl first became interested in marine migration after his

first visit to the Marquesas Islands in Polynesia in 1937-38.

Trained as a biologist at the University of Oslo, he had specialized

in studying animal and plant diffusion to Oceania. He noticed

that a number of the most important food plants cultivated in

aboriginal Polynesia, as well as the Polynesia dog, appeared

to have spread from South America prior to European arrival.

That's when he became suspicious of anthropological dogma which

insisted that the Peruvian balsa raft could not have floated

there in pre-Columbian times.

The Trans-Oceanic

Voyages

And that's when he set

out to prove that such migrations were possible. The quest would

take him on four trans-oceanic voyages over a span of 29 years.

The first was the balsa raft, "Kon-Tiki", (1947) which

sailed 4,300 miles from Lima to Polynesia. In 1969 he constructed

a papyrus reed boat, the "Ra" which crossed the Atlantic

via the Canary Current from Morocco, traveling 3,000 miles in

eight weeks and arriving within 600 miles of Central America.

In 1971, Heyerdahl commissioned the Aymara Indians from Lake

Titicaca (Bolivia) to construct a second version of the reed

ship, "Ra II". This one crossed the Atlantic "without

loss or damage to a single papyrus stem" from Morocco to

Barbados in 57 days (two months). For Heyerdahl Mexico should

be perceived as only a few weeks away from Morocco-not centuries

or millennia as had been thought previously.

In 1978, his fourth expedition was of ancient Sumerian design.

The "Tigris", a 60-foot reed vessel, began its journey

at the convergence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and sailed

4,200 miles in 143 days (five months plus) out through the Arabian

Gulf eventually arriving at Djibouti at the entrance of the Red

Sea.

Pyramid Excavations

in Peru

Dr. Heyerdahl's most

recent project is directing archaeological excavations at Tucume,

Peru, South America's largest complex of pyramids (26 large pyramids

plus numerous smaller ones). Curiously, early art found on site

shows boats built of reed bundles as well as balsa-log rafts.

The Tucume Pyramid project is financed by the Kon-Tiki Museum

in Oslo in collaboration with the Peruvian government. Currently,

the archaeological team have interrupted major field operations

to publish their discoveries in a volume to be published by Thames

and Hudson (London) this spring.

The Peruvian Tourist Department has built a site museum in Tucume

to exhibit the archeology findings which include large pre-Inca

adobe reliefs of bird-headed men navigating among ocean fish

on reed-ships which depict a cabin on deck and rows of oars in

the water.

In the meantime, Heyerdahl has initiated a purely humanitarian

development project in the neighboring town of Tucume, named

"Tucume Vivo" in honor of the local village people

who are descended from the former pyramid builders. Its sponsors

(a private Norwegian welfare organization and the Norwegian government)

have equipped the town with running water, a sewer system, schools

and inventory, bridges, irrigation channels, dams against floods,

etc. Plans also include the construction of a technical school.

Heyerdahl has been criticized as being a showman and adventurer.

Since he does not act like a scholar in the conventional, traditional

sense of the word, his academic colleagues have often been disgruntled

and skeptical of his work. But Heyerdahl insists that his work

is based on solid research. Despite his successful voyages, some

people still find it hard to accept alternatives to the Trans-Bering

Straits Hypothesis for migration from the Old to the New World.

And some still can't believe that reed boats are seaworthy enough

to have made long ocean voyages prior to the European efforts

in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Environmental Concerns

Despite the fact that

Heyerdahl formally researches ancient history, he has always

advocated a deep concern for contemporary problems. When his

reed boats encountered oil slicks and chemical pollution spills

in the ocean in the late 60s, Heyerdahl was the first to send

a report to the United Nations and appeal to governments and

international environmentalists. He has since testified on ocean

pollution for governmental and scientific institutions in 23

countries, including the US Senate and the Soviet Academy of

Sciences.

Heyerdahl is convinced that if more money were spent on the environment,

there would be fewer wars. "History and archaeology both

show us that no progress in the quality or quantity of arms can

secure peace. It can only lead us into ever more horrible and

inhuman wars. Therefore, we should be spending more money on

research related to environmental protection of our globally

deteriorating planet than on arms to protect ourselves from each

other.

This is our only alternative; otherwise we will all sink together

by undermining the delicate and highly complex environmental

ecosystem, thus committing suicide by interfering with biological

recycling and hastening climatic changes."

By studying the past, by searching for missing gaps in the prehistory

of mankind, Heyerdahl is hoping to find links that tie humanity

together. It's his way of trying to persuade contemporary man

that we are really of one blood and, therefore, have even one

more reason to work together to preserve our future.

Further Resources

Dr. Heyerdahl's voyages are documented in various books and films-"Kon-Tiki",

"The Ra Expeditions" and "The Tigris Expedition".

The most famous expedition was Kon-Tiki, and Heyerdahl's book

describing the voyage has been translated into 67 languages while

the film was awarded an Oscar. As well, he has written Aku-Aku,

Fatuhiva, Early Man and the Ocean: A Search for the Beginning

of Navigation and Seaborne Civilizations and the Art of Easter

Island and The Maldives Mystery as well as several scientific

volumes and articles. The most recent biography is Thor Heyerdahl,

the Explorer, 1994 by J.M. Stenersens Forlag, Oslo.

From Azerbaijan International (3.1) Spring 1995.

© Azerbaijan International 1995. All rights reserved.

Back

to Index AI 3.1 (Spring 1995)

AI Home Page

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

Dr.

Thor Heyerdahl in Baku, November 1994. Book is Russian

Dr.

Thor Heyerdahl in Baku, November 1994. Book is Russian