|

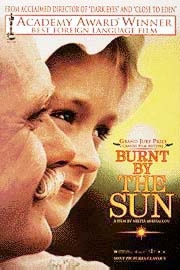

Summer 1995 (3.2) The Scorching

Sun by Betty Blair See Also:

It must be thrilling to be acknowledged internationally with one of the highest accolades in the film industry. What does winning this Oscar mean to you? When film director, Nikita Mikhalkov, went on stage to accept the trophy, if you recall, he took his eight-year-old daughter, Nadia, who had starred with him in the film. They asked what the Oscar meant to her and she replied, "Well, I hope, at last, that they'll buy me a bike!" I don't know exactly what my "bike" will be, but this honor is extremely important. We've always grown up with the idea that the Oscar is something extraordinarily unique - something very honorable. As a professional cinematographer, I feel a deep respect for this prize. Somehow, it seems that among Europeans there's always a feeling that the Oscar is much more difficult to win than, say, the Cannes Festival. Perhaps, it's because Hollywood is geographically further away that this perception exists. However, "Burnt by the Sun" took both awards this year - the "Grand Prix" at the 47th International Cannes Film Festival (May 22, 1994) and "Best Foreign Language Film" at the Oscars (March 27, 1995). That's an extremely rare combination. European cinema and American cinema are based on very different criteria. What is liked and understood in Europe may not be duly appreciated in the U.S. and vice versa. We're immensely pleased that the film won both prizes plus the "Prix du Jury Oecumenique" issued by the Prince of Monaco (May 19, 1994).

Did you expect to win? Up even until the very last

minute, I never expected it. Not at all. We didn't even bother

to take our cameras along. So when we did win, we weren't able

to take any personal photos. Last year we had also been nominated

for an Oscar for "Close to Eden" which everybody had

liked. Despite its popularity, it didn't win. So we didn't have

high hopes this year because not many people had seen our film.

Besides, there are always so many political reasons and nuances

why any film wins an Oscar. Sometimes, it's merely respect for

a specific actor, actress or director. And this year, there were very good films in the foreign category, especially Macedonia's "Before the Rain," and Taiwan's "Eat Drink Man Woman". So we were very surprised to win. Actually, this is the third time that one of Mikhalkov's films has been nominated for an Oscar. That's a rarity for a foreign director, though not so unusual for Americans. What exactly was your role in the creation of this film? I was involved from the inception of the idea, from the very first word right up to the very last moment. I was basically involved with writing and cinematography. Everything - all the dialog and all the scripted action - emerged from working together with Nikita. But the credit for transforming the written word from paper to action on the screen must be credited to the artistic ability of the director Nikita Mikhalkov. What were you trying to say in "Burnt with the Sun"? The story line focuses on Stalinism and its devastating impact on the life of an individual Bolshevik colonel. It's about Stalinist purges. The main image - the "Sun" - is Stalin. Totalitarian systems are "governable" or manageable only up to a certain point. Afterwards, they take on a life of their own, destroying not only those whom they were originally intended to destroy but their creators as well. Specifically, we had in mind the immense system of the Soviet Union. But you'll see that we're not blaming anybody. We're merely trying to show that everyone became a victim.

Were

you only addressing communism or did you have other systems in

mind? Could you have made this

film ten years ago during the Soviet period? What do you mean by that? These days, there is a rush

to destroy everything that relates to the past. But we must be

careful not to discard and purge everything. So many people are

cursing all the old idols-the exact idols that they used to worship.

I've never been a communist. So I'm quite removed from all this.

But I never try to blame or insult anyone who was, or may still

be, a communist. What is the creative process like for you? When it comes to films that

Nikita and I have worked on together, the ideas and concepts

emerge from the problems that we see occurring around us. We

spend a lot of time together, discussing all these issues. We've

worked together, on and off, since 1971. Eventually, we settle

on a problem and develop it together. So then, what do feel are the most pressing problems these days? Currently, we're living in a quiet period - more or less. It's time we got rid of these negative features and became human beings in the real sense of the word. Throughout the whole evolutionary period, mankind has been striving to find out how to become really human. This is where literature plays an immensely important role. Everyday of our lives is a struggle - a fight with our own nature. Everyday we have to suppress the evil within us. And yet, it seems, centuries will be required before mankind can achieve this ideal. What problems concern you most about Azerbaijan? I'm very much concerned about

what is happening in Azerbaijan. The ultimate question is whether

Azerbaijan can continue to exist as an independent state. There

are tremendous influences at work, pulling from opposite ideologies

and geo-political tensions. I'm absolutely convinced that there

are outside forces that wish Azerbaijan's annihilation as an

independent state. Fortunately, the standards of the international

community are placing restraints on these tendencies; otherwise,

we would have already been wiped out. What specifically are you referring to? There's a great latent struggle

going on. However difficult it might be, we can resist outside

influences. In reality, the only way to destroy us is through

internal dissension and disunity. There are enemies trying to

destroy us from within, and their success will depend on whether

we are able to forget our ambitions, claims - despite how justified

they may be. We must put them aside, at least temporarily. We

need to forget these things for the present and concentrate on

the one major problem - our mere survival as a single nation and

a single people. Back to you personally, how did you get into writing in the first place? By mere chance. It was purely

accidental. By training, I'm an engineer. I had been involved

with science for quite some time before I started writing. But

in our family there is an incredible regard and respect for the

written word. My older brother Magsud is known as a prose writer.

I wrote my first story when I was 23 in 1962. My own work in

professional writing began in 1966 when my first novel was published. Do you write differently now than during the Soviet period? I've always tackled subjects that were interesting for me and never forced myself. I abide by the same principles now as I did before. The very fact that the three previous parts of the novel that I have just finished were published ten years ago and the fourth part ("Solar Plexus") is coming out in Baku in two or three months proves that my writing remains the same. Are any of your works in English? No, not yet. Not that I know

of. Nikita and I have plans to publish the collection of our

joint screenplays in English - all four of them. From time to time,

my works have been translated in Russian by the Progress Publishing

House and some have been translated into some of the European

languages. What's happening with Azerbaijan's filmmakers these days? A couple of months ago, I was inside Baku's huge Film Studio but the building was nearly vacant. When it comes to cinematography,

unlike writing, you can't do it alone. It takes a lot of resources.

The industry is in a critical situation-primarily because of

economic need. Cinematography is a field that, to some extent,

depends on outside financing. We're trying the field in Azerbaijan.

We've finally succeeded in getting some money from the government

and plan to shoot two or three films in the near future. This

is a significant step forward. Recently, there have been some

commercial films shot by private studios which were not of the

best quality. The situation is difficult because it's not always

the most talented who succeed in getting financed. What about film in Azerbaijan? What do you see in the future? We have great aspirations. The

Union of Cinematographers, of which I am Chair, hopes to get

support to establish the Baku Annual International Film Festival

which would be sponsored by the Consortium countries. If we succeed,

it would be the first genuine international film festival as

it would be organized and managed not by one country but several.

We're in the process of organizing it right now and hope that

after about a year to get started. Such a festival would do wonders

to activate the cultural life of Azerbaijan. Back

to Index AI 3.2 (Summer 1995) |