|

|

|

|

No Guidelines Today

Now there is no Party

or State Resolution in regard to art and literature. The democratic

aesthetic has been developing for centuries-since ancient Greece-and

still exists today. We also rely on our own traditions in aesthetics,

literary and critical thought. Before the State used to interfere

even with our classical works. Publishing houses were required

to cut sections from works when they didn't conform to "Soviet

reality." The classical "divans", for example,

contained certain sections called "minajat" where the

poet addresses God at the conclusion of the work, and another

section called "qasida" where he praises the Prophet

Mohammad. These sections were eliminated from the works of Nizami,

Fuzuli and other classical poets, despite the fact that they

were penned centuries earlier.

When I published the "Memoirs" of my father, they took

out the chapter dealing with the Noruz holiday (Spring-March

21st). I petitioned the Department of Ideology of the Central

Committee of the Soviet Party only to be told that Azerbaijanis

had only one holiday-the Great October Revolution. I had no choice

but to publish the book without that section. That was 1960.

My father felt a lot of pressure as a writer and for no serious

reason. People used the word "angel" when they referred

to him. No writer celebrated his Jubilee as young as 40 [usually

Jubilees begin at 50 or 60]. But my father was so dearly loved

by his students that they carried him in their arms from his

home to the Jubilee Hall. Actually, I think his "angel"

character saved him from the Stalin Repression in 1937 because

he had been a member of the Musavat Party which was the leading

part of the Azerbaijan Republic in 1918-20 which opposed the

Soviets. Most party members either escaped abroad when the Soviets

came in 1920, or they were captured and exiled in Siberia. Also

my father had written about 10 articles in the spirit of pan-Turkism.

But it was when his brother, Akhund Talib Yusufzade, left for

Turkey that he began feeling pressured.

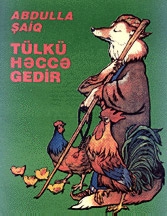

My father was a great educator and teacher. In some of his works

written for children, we see motifs that can be appreciated by

grown-ups as well. For example, in his work "The Fox Goes

on a Pilgrimage" ("Tulku Hajje Gedir") the cunning

fox becomes the symbol of the two-faced representatives of religion.

Did he really intend such works for children or for grown-ups?

I think both. Ten years ago they created an animated version

of this story but soon the film was forbidden. Why? Probably

because some leaders recognized themselves.

Trends Today

It's very difficult

to say what is happening in Azerbaijani literature today. It

takes considerable time to assess the literary process. It's

difficult to see these changes when we are in the middle of them.

Ten years from now, we'll look back and assess this period more

accurately.

Generally speaking, I'm not aware that there is as much literary

talent today as there was during the Soviet period. But there

are still fine works being produced by writers such as Sabir

Ahmadli, Isa Husseinov, Yusif Samadoglu and others.

Movlud Suleymanli's work, "The Mill" marks the beginning

of a surrealistic trend in Azerbaijani literature. In this work

you find an analytical approach along with metaphoric expression.

All the problems of the village become evident through the conversation

of the people sitting together at the old village mill.

Today is a very difficult period for writers, scholars and other

professionals in the arts; they don't yet feel stability and

certainty. Nor have they been able to find their places in the

market economy. For example, up until recently, I had always

worked in the Academy of Sciences. My salary was sufficient to

live quite well and even to travel on holidays every year. But

now I have to supplement my salary by teaching at one of the

private universities. At the age of 72, this is the only way

I can earn a living for my family.

The Writer's Union no longer takes care of its writers. It used

to be that they would assist in getting works published, help

writers get apartment and funds. The building used to be alive

with intellectual discussion. But most writers don't expect anything

from them any more. Writers who manage to publish anything today

do it through their own personal relationships.

The main problem of Azerbaijani literature is that it has always

focused on people and their relationships to society. During

the Soviet Period, writers had to conform to the Soviet system.

You had to describe his "happy" life in the Soviet

society. They wanted all the writers to develop what they called

"the realistic style."

But a writer like Samad Vurgun was romantic. He was born that

way, it was his nature. How could he have been a realistic poet?

Let me give you an example of how such writers managed to succeed

under such restrictions. My father had an epic poem, "Gochpolad,"

which described the national liberation movement in Azerbaijan

in the 18th century.

Back in 1937-38, he submitted the poem to one of the magazines

which promised to publish it, but only after a year. It was Vurgun

who advised my father to add a line using Stalin's name. My father

was shocked. How could he add the name of Stalin when the poem

was set in the 18th century? Eventually, he found a way to do

so and the poem was published immediately. You see what kind

of things were happening? Sometimes, I feel ashamed of the things

that we had to do in the past. But we did it to survive.

Samad Vurgun wrote 18 poems about Stalin. He saved himself and

he also was able to help his people to a certain degree. Had

he not done so, could he have spoken out against the Russian

alphabet in one of the Supreme Soviet meetings? Could he have

criticized the frequent alphabet changes in Azerbaijan? You have

to understand the context in which we lived and worked, then

you'll understand our pressures and predicaments and why our

new-found freedom is so valuable to us.

Talibzade is an Academician at Azerbaijan's Academy of

Sciences and one of the best-known literary critics in Azerbaijan.

For more than 50 years, he has been working at the Nizami Institute

of Literature and has authored approximately 30 books and 300

scholarly articles. His father was Abdulla Shaig, a famous children's

writer (1881-1959). Jala Garibova interviewed Talibzade for this

article.

From Azerbaijan

International (4.1)

Spring 1996.

© Azerbaijan International 1996. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 4.1 (Spring 1996)

AI Home | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us