|

Winter 1996 (4.4)

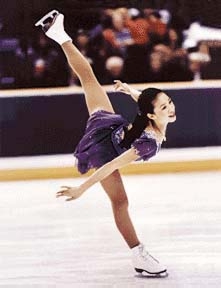

The orchestral works of Azerbaijani composer Fikrat Amirov are often heard in Baku's ornate Ballet and Opera Theater, the Philharmonia, and the Republic Palace. But lately, Amirov's music has found a new venue and is being discovered by an entirely new audience. Sixteen-year-old Michelle Kwan, a Chinese-American from Los Angeles and winner of the 1996 World Championship Figure Skating Competition, is skating to Amirov's music in competitions all season as she prepares for the 1997 World Championships to be held this March in Lausanne, Switzerland. We found Michelle's choreographer, Lori Nichol, in Toronto, Canada, and asked how she had chanced upon this composer who is highly esteemed in Azerbaijan, but is known so little beyond the borders of the former Soviet Union.

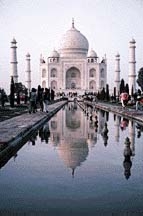

Photo: The Taj Mahal inspired Michelle Kwan's latest choreography. Courtesy: Archives of the Consulate of India, Los Angeles. "Very few orchestral pieces are left that play well in a huge arena filled with 20,000 fans," observes Nichol. "You need something dramatic and full of energy that commands attention and yet fulfills all the other requirements of the program, as well. We thought the Amirov piece could do it." It's no exaggeration that Nichol listened to hundreds and hundreds of symphonic pieces this past year before coming across Amirov's "Gulistan." Nichol, who has created hundreds of programs, is always in search of new music, convinced that fresh ideas and fresh interpretations give the skater an "edge" in competition. That's why she devotes nearly the entire year to listening to symphonic music to find the pieces she thinks will choreograph best. "I have a strong memory for steps that I've choreographed in the past. When I hear a piece of music that I've worked with before, it's very hard for me to mentally erase the original movements that I've come to associate with it. That's why I like the challenge of identifying new music." Michelle's coach, Frank Carroll, judges music in terms of whether or not it is memorable. "When the event is over, I want people to go home humming the melody or, at least, having it play over and over in their minds." No doubt, he's counting on the subconscious power of the music to influence the judges over the duration of the season. Carroll should know what works. From his training camp at Lake Arrowhead in the San Bernadino Mountains east of Los Angeles, he has trained numerous skaters who have gone on to become national and international champions. But there's more to choosing music for the ice than mere personal preference. Rules of competition place severe restrictions on the selection process. For starters, vocal music with lyrics or words is not allowed. A new rule, however, passed in June 1996, permits music that uses voices as instruments. It was a lucky break for Nichol as she wanted to choreograph Amirov's ballet, "The Arabian Nights," for another young skater, Jere Michael, who is trying to qualify for the U.S. National Championships. Nichol found the music to be "absolutely gorgeous," and was so glad the rules had been changed so that she could develop it. But the greatest restrictions have to do with the duration of the piece. Competitive skaters perform two programs. The Short Program cannot exceed two minutes and 40 seconds. Eight separate elements-spins, spirals, footwork and double- and triple-rotation jumps-must be performed in that brief time. The Free Program can extend to four minutes and 10 seconds for women. This program gives skaters a chance to highlight the movements they do best. Michelle does seven triple-rotation jumps, two double axles, as well as spins, steps, and freestyle moves that she thinks best exhibit her artistry and flexibility. The Free Program counts for two-thirds of the total points of the combined performances. According to Nichol, the music has to build at precisely the right moments-both in terms of tempo and crescendo. But that doesn't mean that a piece will work well if it's all "vivace" or "presto." Typically, music is chosen which has a change in tempo or, at least, a pause to give the skater a chance to catch her breath. And a piece must always resolve itself in a climax within the given time frame. With all these requirements, it's no wonder that skaters settle for pieces that have been used over and over again, such as "Romeo and Juliet" by either Tchaikovsky or Prokofiev, "William Tell Overture" by Rossini, Hungarian Dances by Bartok, "West Side Story" by Bernstein or other pieces by Rachmaninoff or Chopin. Finding Music

After making her selections, she places up to six CDs into the built-in CD player in her car, and listens all the way back home to Keswick. She quickly scans past the material she know won't work. "I'm probably a hazard on the freeway, with a baby in the back seat and me, listening so intensely to music. I've missed my exit more than once," she confesses. Soon after Nichol found the Amirov piece, Michelle flew to Toronto, and the two tried the music out on the ice. "Sometimes, you hear a piece in the comfort of your studio and it sounds wonderful, but then when you try to skate to it, it simply doesn't work," says an experienced Nichol, who won second place in the 1983 Professional World Championships. But Michelle loved the Amirov piece immediately and found it exotic and mysterious. The next task was to begin the long and arduous task of editing. The "Gulistan" piece at 16 minutes in length was considered quite long to edit down to a mere four minutes. Nichol found herself listening to the entire production over and over again. "It's a tough job when you're trying to stay true to the composer's original intentions. Our goal is to maintain the essence of the piece and truly reflect the spirit of the composer, while at the same time support the technical aspects of skating as well."

Editing was a tedious job that took weeks. "We must have edited about 20 different versions from beginning to end before we were satisfied." After that, Nichol and Kwan began to choreograph. Amirov's piece is defined as a "symphonic mugam" (pronounced moo-GAM) in the spirit of traditional Azerbaijani music. "We had a lot of difficulty trying to figure out what 'mugam' meant. We took it to a music professor, we called friends, and we asked people with music degrees, but no one could give us a meaningful answer. In the end, we followed our own intuition. We felt that simply enjoying the energy and passion of Amirov's piece was more important than being able to describe it theoretically." Next, because the music had such depth, they felt they should develop a story line. "It just seemed to be saying something to us, so we took artistic license and created a love story," Nichol says, reflecting on the creative process. It turns out that her intuition was right. "Gulistan" means "place of flowers or flower garden," and "Bayati Shiraz" is the name of one of the classical modes of mugam which is very popular in Azerbaijan. This specific mode is made up of musical intervals that are believed to inspire feelings of well-being, passion and love. The CD liner notes indicate that Amirov had been influenced in his composition by the poetry of the Persian writers Hafiz (13th century) and Saadi (16th century). Unfortunately, no mention is made of the specific poems. The Taj Mahal Story Line Listening to it for the zillionth time, Frank finally said, "Well, what about the Taj Mahal?" Could they choreograph the piece to personify the splendor of this beautiful architectural monument? But the Taj Mahal is in India, not Azerbaijan. They wondered if they should dare such a combination. "We both love the Taj Mahal even though we've never been there," says Nichol. So she headed to the library in search of more information. She discovered that the monument was completed in 1643 after 22 years of construction. The council of architects involved was quite cosmopolitan for its day, including experts from India, Persia and Central Asia. Shah Jahan had dedicated the Taj Mahal to the memory of his wife, Arjumand Banu Begam, who had died in childbirth. She was often called "Mumtaj Mahal," which translates as "Chosen One of the Palace." Finally after much searching, Nichol found a quote describing the memorial: "Both inside and out, the marble reflects the light and mood of the changing day. Dazzling at noon. Warm and glowing at dusk. Soft and ethereal in the moonlight like the varying moods of a beautiful woman." And based upon that description, Nichol and Carroll created the choreography-the imagery of the sun as it shines against the white marble of the building casting various shadows and creating different moods. The artistic movement climaxes in the evening when the story reveals the spirit of Mumtaj rising out of the crypt, searching through the halls of the mausoleum for her husband and then dancing with him. Then, just before the sun rises for a new day, she disappears in despair back into her grave. According to Nichol, so many details have gone into choreographing this piece, even down to the smallest rippling movements of the body and facial expressions. The performance is filled with such subtleties. "Part of what I'm trying to do in the choreography is to touch the hearts and imagination of people," Nichol confides. "That's what Michelle is trying to do, too. We're trying to give a gift to the people who are watching. And if, in the process, we're able to attract attention and focus upon a culture such as Azerbaijan's that is relatively unknown, because of our choice of music, well, then, that's an added bonus!" "But I hope we haven't offended Azerbaijanis by having chosen a story line based on the Taj Mahal. It all somehow felt so relevant-the majestic, rich music personifying such an extraordinarily beautiful monument." According to Nichol, Amirov's "Gulistan" is extremely powerful music and, therefore, requires an extremely adept and powerful skater like Michelle to perform it. "The music is so strong that if the skater isn't exceptional, it would make her look weak." "The performance is over so quickly," she observes. "I don't think people can really comprehend the complexity and difficulty of Michelle's performance-perhaps not even some of the judges. I think you would have to get a video of her performance and play it over and over again, slowly, to really comprehend the level of difficulty at which she is performing. She's really phenomenal!" Michelle is busy now perfecting the Amirov piece, which she will perform in at least three more competitions, culminating in the World Championships which are being held in Lausanne, Switzerland, March 17-23, 1997. So far she has won first place in all three competitions in which she has participated. Still to go are the Ultimate Four on December 22, the U.S. National Championships from February 10-16 (televised) and the Champions Series Finals from February 27-March 1 (televised).

Current information about Michelle Kwan is available at Web site<http://turnpike.net/~adweb /kwan/index.html>. Fikrat Amirov's "Gulistan Bayati Shiraz" is available as a CD on the Olympia Explorer Series Label, OCD 490. The performance was conducted by Azerbaijani Yalchin Adigezalov with the Moscow Radio & TV Symphony Orchestra in Moscow in 1993. From Azerbaijan

International (4.4) Winter 1996. AI Home | Magazine Choice | Topics | Store | Contact us |