|

Spring 1997 (5.1)

Pages 30-37

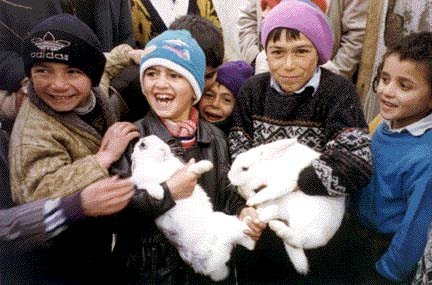

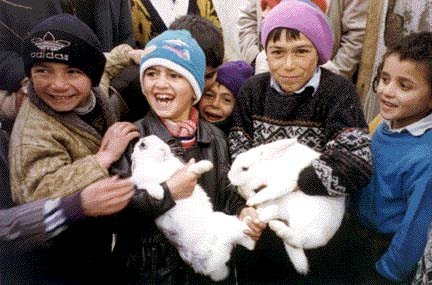

Kids at the Sabirabad #1

camp in Azerbaijan where 12,000 refugees live."Do you want

to see our rabbits?" they asked the journalists.

Photo: Blair (January 1997.)

The 2 1/2-hour drive from Baku

to Sabirabad is lonely and desolate. Pelican-like oil pumps slowly

work the barren land. Discarded pipes of all sizes lie abandoned

in the fields. Snow-covered mountains press down upon the horizon.

There are seven refugee camps in this region. Camp Number One

was once an empty field spread just beyond the railroad tracks.

It's located about four kilometers from town. A sign at the camp

entrance indicates there are several schools and a hospital on

the grounds. Recently, a mosque was built.

Photo: Elnur Babayev (1996) Photo: Elnur Babayev (1996)

The morning rains have

turned the paths into sludge-mud sucking at your heels. Around

12,000 Azerbaijani refugees live here. It's the largest of all

the camps by far. Typically, 4,000 to 5,000 people reside in

each camp. For many, this is the beginning of their fourth year

in Sabirabad.

The refugees live mostly in mud brick homes, whose single rooms

are covered with blue plastic tarps donated by the UNHCR (United

Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). They've built these

mostly by themselves to replace the worn-out tents they used

to live in. Additionally, most families have improvised some

sort of entranceway with reeds available in the nearby marshlands

to protect against the weather. It also serves as a place to

take off one's shoes before entering the main room-a practice

observed rather strictly. There are still some tents left from

earlier years, weather-beaten from the sun and wind. Most now

serve as adjuncts to the mud brick homes and are used for storage

or poultry coops. Chickens, turkeys and geese peck around in

the dirt.

Small limestone buildings are scattered throughout the camp which

serve as toilets. Each has four narrow compartments. There are

no doors, although a free-standing wall in front of the structure

gives some privacy. But far too many people have to share the

same facilities. As it is winter, the floor and foot grips are

covered with mud and excrement. A small twig broom leans in the

corner. There is no electricity for trips that must be made in

the night.

Interspersed throughout the camp are several outdoor mud ovens

for baking tandur-style bread. Women slap the dough against the

inner walls of the oven which is fired by burning twigs and dried

cotton plants. Bread is the sustenance of life in the camps,

so the light drizzle of rain and snow doesn't deter their efforts.

A few mud brick kiosks are set up to sell candy, soft drinks

and cigarettes. These simple shops provide the only outward signs

of economic activity. Ironically, the colors and slogans of foreign

labels make the camp seem less isolated.

Women walk around outside in housecoats. Boys dash back and forth

in mud-covered slippers or shoes which are usually several sizes

too large for them.

At one end of the camp is the distribution building of the Federation

(Red Cross and Red Crescent) which supplies the refugees with

food. Rations have diminished over the years. "Donor fatigue"

and too many other needy people in other parts of the world have

drained the limited funds. This month, each camp resident is

receiving five kilos of flour, one kilo of navy beans (rice is

substituted some months), 250 grams of black tea and one liter

of vegetable oil. That's all. No fruits or fresh vegetables.

No meat, although there have been occasions when canned meat

was included. And this month, no sugar.

About a dozen badly weathered tents serve as a school. Each tent

accommodates about 20 students at double desks. There is nothing

on the walls to stimulate learning. Nor are there any books,

resource materials, audio-visual aids, pads of paper or even

pencils stacked up anywhere. A few students are lucky enough

to have first-year primers in the new Latin alphabet which appear

very ragged from being handed down year after year. These rare

paperbacks are also much too basic for older students.

Two-hour shifts allow for three rotations a day. Teachers complain

about the dirt floors, the holes in the tents that leak during

rains, and the ever-present cold that numbs hands and feet in

the winter. Kerosene is so expensive that the school rarely has

access to it. And electricity is sporadic, at best. "Can't

you help us?" the teachers implore.

Left: A refugee woman reduced to gathering

dried sheep manure from the fields to warm her mud brick home

in Sabirabad camp.

Right: Kerosene for heating refugee homes is

very expensive in many refugee camps. In January 1997, the price

for less about two gallons of "neft" was about $1 in

the No. 1 Sabirabad camp. Most families have no income. Both photos: Blair (January 1997).

"At the end of this year, we'll go back"

Yadigar Maharramov (age

32) is a former driver, and his wife, Zamina Mammadova (age 31),

is a former school teacher. They have an 8-year-old son, Elshan,

and a 10-year-old daughter, Lala. They fled the town of Jabrayil

in late September 1992.

Behind the thin wooden door, their single room is small but tidy.

Twin-sized beds line the opposite walls, blankets pulled taut.

A kerosene stove dominates the middle of the room, and a television

sits in the opposite corner.

Despite the mud and bits of litter scattered outside, the place

is immaculate. A Federation calendar is tacked high on the wall.

Lala is one of the children beaming from the photograph.

Two little windows about 18" x 12" provide the only

natural light in the room. A naked light bulb hangs from the

ceiling. The camp now has access to electricity during the day-well,

sometimes. Until the refugees complained to the local government,

they had access only in the evening after six o'clock.

Zamina

keeps her glasses and plates in a low wooden bureau. As we enter,

she pulls several wooden chairs up to the table and immediately

starts organizing lunch. She knew we were coming. Suddenly, soup,

some stew with a bit of meat, bread and tea fill the small table. Zamina

keeps her glasses and plates in a low wooden bureau. As we enter,

she pulls several wooden chairs up to the table and immediately

starts organizing lunch. She knew we were coming. Suddenly, soup,

some stew with a bit of meat, bread and tea fill the small table.

Yadigar served two years in the army when the Karabakh war broke

out. At that time, the villages in and around Jabrayil were losing

10-15 Azerbaijanis a day from Armenian attacks. It was while

Yadigar was away that his wife and two small children had to

flee with Yadigar's brother.

"We knew we would have to leave," Zamina said. "We

knew because of what happened in Khojali where hundreds were

massacred in one night [in February 1992]. And when we heard

Shusha had been captured, we knew we were next. We simply drove

out of town following everyone else who was leaving. I remember

it was raining."

Zamina fled from the 3-room house Yadigar had built himself with

the balcony which overlooked the gardens and fruit trees. She

left behind everything she owned, including the livestock. She

had time only to grab her young children and some bedding.

When Zamina and the children reached the 25-kilometer "no

man's land" between the border of Azerbaijan and Iran, they

thought they would be safe. But the Armenian soldiers pushed

further. So she and her family, along with thousands of others,

were forced to cross over the Araz River into the unknown territory

of Iran. For the previous 70 years under Soviet rule, escape

across the wild, raging waters had always been considered extremely

perilous.

Fortunately, Zamina managed to cross by bridge. Those fleeing

on foot had no choice but to swim. Tragically, many drowned.

For those who did make it, the Iranian government cooperated

by transporting them 60 km further east and then back across

the Azerbaijani border into a safer region near Imishli. It was

there that the Iranian Red Crescent would soon establish tent

camps for nearly 50,000 Azerbaijani refugees.

Later, Yadigar learned that some fellow villagers who had been

taken hostage were forced to set fire to their own houses-after

being looted, that is. The whole village was destroyed. And then

the Armenians left. "No one lives there now," says

Yadigar.

There are about 60 villages in the Jabrayil region. The lower

villages were populated by Azerbaijanis, and the upper ones-about

15 mountainous settlements-by Armenians. "That's where the

attacks came from," says Zamina.

"Despite the fact that we lived in separate villages, the

Azerbaijanis and Armenians were very close to each other,"

Yadigar relates. "We could go stay with Armenians in their

villages, and Armenians could come stay with us in our villages.

After the war started, the Armenian villagers in our region would

often come to us and say, 'This is not our fault. We did not

want this war. The Armenian government and Russia started this

war.'"

But Yadigar says he understands why his neighbors suddenly turned

either nationalistic or passive. "Perhaps, it really was

not their fault. They were terrified of being killed. They were

forced to fight against their Azerbaijani neighbors or else they

would have been killed, themselves."

Yadigar's family moved to the camp in Sabirabad almost four years

ago. Two years later, they moved out of their canvas tent and

into the mud brick home which Yadigar built.

"It's so abnormal, the life here," says Yadigar. "You

can't work. Only a very few children go to school. There's no

oil or fuel to heat them. If it rains, everything gets dirty

and muddy. The roof always leaks."

According to Yadigar, the monthly rations have become smaller

and smaller. The informal system of relatives helping relatives

that enables many in post-Soviet countries to survive does not

play out here because everyone's relatives are also refugees.

The local government gave families 23 liters of kerosene, 2.5

kilos of flour and two boxes of detergent. But that was three

years ago.

Of the 12,000 refugees here, only a few are employed. The Federation

bought some land from the local government and has hired some

refugees to work in the fields. They can earn around 70,000 manats

($18.50) a month. Yadigar was hired by the Federation as a driver

after earning a reputation repairing and maintaining the Toyota

LandCruisers driven by the Federation's staff. He is one of the

lucky ones. "My salary just about covers my needs,"

he says, without disclosing the amount.

Some bartering goes on, according to Yadigar, as well as some

stealing of flour or shoes. But like back home, neighbors watch

out for one another. An additional problem is that the family

unit has become fragmented because so many men are in the army

or elsewhere in cities seeking employment. Says Yadigar, "Much

of the responsibility lies on the shoulders of women who have

no means to support their families."

Yadigar says he could forgive the Armenians if they stopped occupying

the land with their military forces. He would even welcome them

again as neighbors. He reminds us that this is not the first

conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, referring to 1905.

"History gives us hope. Without hope, life would be impossible."

Yadigar believes his children will one day return to their land-"with

America's help," he adds. "They're young. They'll be

able to go back to their homeland again. We always keep telling

them that at the end of this year, we'll go back. Everything

that we're connected to is in Jabrayil. We've left our cemeteries

there-our parents' and relatives' graves. Jabrayil is our motherland.

We constantly dream about going back."

Yadigar and Zamina's children, like most of those we saw at the

camp, appear healthy, happy and loved-quite a parental feat under

the circumstances.

Newborn Brings

Uncertainty

Rana Aliyeva

(age 26) is a high school graduate married to Azer Aliyev (age

27), a former factory worker. Their son Ilham was born on February

26, 1997, three days before our visit.

Rana

gave birth in the small mud house which she shares with five

others: her in-laws, her husband and two children. The baby is

wrapped tightly in a beige and blue-striped blanket, as swaddling

is the tradition. The small room is crowded with relatives and

friends. The midwife sits on the bed beside Rana, who is breast-feeding

the infant. She has been attending the young mother for almost

two weeks. Rana received no professional prenatal care. Delivery

conditions were poor-dirty and cold. There was no electricity

and no running water. As if to add emphasis, the lights go out

while we're talking. No one bats an eye. Azer, her husband, embarrassed

by all this women's talk, stands with his back to the group because

there is no other room to disappear into. Rana

gave birth in the small mud house which she shares with five

others: her in-laws, her husband and two children. The baby is

wrapped tightly in a beige and blue-striped blanket, as swaddling

is the tradition. The small room is crowded with relatives and

friends. The midwife sits on the bed beside Rana, who is breast-feeding

the infant. She has been attending the young mother for almost

two weeks. Rana received no professional prenatal care. Delivery

conditions were poor-dirty and cold. There was no electricity

and no running water. As if to add emphasis, the lights go out

while we're talking. No one bats an eye. Azer, her husband, embarrassed

by all this women's talk, stands with his back to the group because

there is no other room to disappear into.

Azer receives 90,000 manats (about $22) a month as a wounded

Karabakh veteran. His parents each get 20,000 manats ($5) a month

in pensions. The family also receives some rations, but complains

that it is far from adequate. "Some days, there is not enough

bread to feed the children," Rana says.

Rana is originally from Tbilisi,

Georgia. In 1991, she married Azer who is from the Fuzuli region

fairly close to Azerbaijan's western border with Armenia. They

fled their village on September 23, 1993. Rana said the attack

came very suddenly while she was eating lunch. It was cold and

raining. They were terrified of being taken hostage. Azer was

in the hospital, so she and the children fled to Iran alone.

A neighbor happened to be driving by in a truck and picked them

up. Otherwise, they would have had to continue on foot.

"We didn't take anything," Rana said. "Only the

children." She has two children now, but lost her 3-year-old

soon after arriving in Sabirabad. Her son had been weakened by

the coldness of the flight, and Rana had had no money for medicine.

Rana's midwife, who has a basic medical license, also does gynecological

work in the camp. Back home, she averaged around 170 deliveries

annually. Last year, she helped deliver more than 30 babies in

the camp. "In my experience, I'm proud to say, I haven't

lost a single child," she boasts. "But in the hospital,

they die." The cries of Rana's newborn are a constant reminder

of the clouded, uncertain future.

The midwife feels bad that the problems inherent to a refugee

settlement are spilling over to the local population. "It's

crowded here. There's malaria, flu and tuberculosis. But it's

not our fault. We're all victims of this war."

Obviously, Rana and her family's primary wish is to return home.

But their second wish? "To have good conditions here,"

says Rana. "The children can't study, can't go to school.

They're growing up uneducated. It's a terrible tragedy for us."

How does everyone keep from becoming depressed or going insane?

"Hope," the midwife says. "And President Aliyev.

Because of his political skills, he has interested other countries

in Azerbaijan. Because of him, the world now recognizes Azerbaijan

as an independent country. He knows that the only way to solve

this conflict is through peace."

Unspoken Horror

Pari Guliyeva (age 34)

is a former kindergarten teacher. Her husband used to be a laborer

and tractor driver. They fled Zangilan with their two children-Khumar

(age 11) and Urkhan (age 7)-in 1993.

The room is immaculate. There are no chairs, so we sit on the

floor on pillows. There's one bed and a brightly painted wooden

marriage chest. Khumar's family also crossed the Araz River into

Iran. Her uncle had picked them up on a tractor. Khumar was 7-years-old

at the time. They stayed three days in Iran and then 15 days

in Imishli before coming to Sabirabad. They slept in the fields,

and when it rained, they found shelter underneath the tractor.

"I was so scared that they would take me as a hostage,"

says Khumar. "They captured my father. He got very sick.

He was in the hospital for five months. He can't speak now."

Khumar's father, separated from his family, swam across the Araz

River to Iran. He has suffered severe shock. His family believes

he was beaten or tortured as a hostage. Four years later, he

is only now beginning to regain his ability to speak. He is not

at all himself, and this is very disturbing to young Khumar.

"She always cries when she thinks about her father,"

says Pari.

Khumar used to receive good marks in school back home, but rarely

attends classes now. The school has little heat or electricity.

The shame factor plays a role as well. Khumar and her younger

brother Urkhan are embarrassed because they don't have good clothes,

school books, pencils or book bags. And yet Khumar still dreams

of becoming an educated professional. "I want to be a doctor

so that I can help sick people," she says.

Pari's family built their mud home themselves. Khumar helped

pour and shape the bricks. Her regular chores include fetching

water from the pump and washing clothes. She likes to knit and

has made several pairs of woolen socks. And she enjoys singing

and dancing. She followed us all day through the camp, delighted

by our presence.

Lingering Images

We visited others whose

stories are much the same - the trauma of flight, the struggles

of survival, the psychological displacement that affects everything

they think and do.

The children are mostly in good spirits. The resiliency of youth

constantly amazes you. Bright smiles flash across their faces.

But on those of the older people, particularly the mothers, their

pain is deeply etched. No matter how hard they try to smile,

their eyes tell a different story.

Climbing into a warm and dry car to leave the refugee camp weighs

down upon your conscience. So many images flash back through

your mind - so many contradictory feelings. You are treated like

a hero for making the day brighter, but you know you are not.

You agonize over your inability to soothe and comfort. Pulling

away from the camp, you try to cast a sympathetic glance toward

the men standing silent as stones, staring without expectation.

A grinning child runs alongside you, his slippers barely staying

on his feet. From the back window of the car, the smiling eyes

and waving hands soon blur into one mass of suffering, but you

know within each mud brick room, the pain is solitary and unique.

Caleb Daniloff, Ruth Daniloff, Khumar Husseinova and Betty

Blair contributed to this article.

From Azerbaijan International (5.1) Spring 1997.

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 5.1 (Spring 1997)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|