|

Autumn 1997 (5.3)

Pages 24-29

By the beginning of the 20th

century, the oil boom in Azerbaijan had reached its peak, and

Baku-once a sleepy medieval city-had become the center of an

oil industry, producing more than 50 percent of the world's supply

of oil. In this newly charged atmosphere, there was a rapid influx

of ideas from other countries, especially from Europe. For instance,

film enjoyed an early introduction to Azerbaijan, arriving there

just a few years after its invention in France. In the following

article, Asim Jalilov provides a sense of what has happened to

film in Azerbaijan as filmmakers sought to reflect a true slice

of life through the artistic form of motion pictures.

On May 14, 1916, Baku cinema goers were stunned by the premiere

of a movie entitled "In the Realm of Oil and Millions."

The film was based on a novel by Ibrahim Musabeyov and opened

at the "Biography," a very fashionable theater those

days.

In the story, a group of local men try to convince residents

that oil deposits worth millions literally lay at their feet.

To access it, one had only to pierce the road with something

sharp, such as a walking stick. The hero of "Realm,"

it turns out, ends up making a fortune on a field two steps away

from the corner of his house.

Left: From "Sevil," 1929. The film was directed

by A. Beynazaro and the screenplay written by Jafar Jabbarli.

The film deals with women's rights. It challenged women to take

off their veils. Left: From "Sevil," 1929. The film was directed

by A. Beynazaro and the screenplay written by Jafar Jabbarli.

The film deals with women's rights. It challenged women to take

off their veils.

The movie, a melodrama,

was produced at the local studio "Film." It astounded

moviegoers from all backgrounds, not because of any unusual special

effects, but simply because the filmmaker managed "to show

everything as it is," without artificial nuances. Up to

that time, audiences were mostly used to watching entertaining

pieces about life abroad-films based in countries like France,

Germany and England. "Realm" provided one of the first

opportunities for Azerbaijanis to see their own native city and

their own people in motion pictures.

The movie was an eye-opener. It showed a world of glaring diametrical

opposites, a bipolar society eternally divided between rich and

poor, strong and weak, where the interests of one group clearly

did not coincide with those of the other.

The most striking scenes showed sweaty, dirty laborers working

in filthy, polluted oil fields. For the first time a filmmaker

dared to show the truth, no matter how bitter it was. He challenged

the audience's feelings of sympathy while leaving the final judgment

up to them.

The trend toward realism continued in the movies that followed

as there were no restrictions concerning the filmmaker's choice

of topics. Problems began to arise, however, when the Bolsheviks

came to power in Azerbaijan in 1920, causing the collapse of

the short-lived independent Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan

(1918-1920) and the eventual establishment of Soviet Azerbaijan

(until 1991).

Movies for the

Masses

The Commissars who led the movement in Baku not only monopolized

the government and abolished personal property; they also interfered

with intellectual and spiritual spheres. Only two attitudes were

allowed: condemnation for everything connected with the past

and praise for everything related to a new set of values based

upon the Leninist interpretation of history. The slogan "Anyone

who is not with us, is against us!" won widespread acclaim.

The wave of nationalization affected everything, including cinema,

which Lenin deemed "the most important of all arts,"

since he believed they were the best way to propagate revolutionary

ideas to the masses.

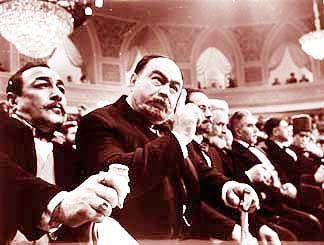

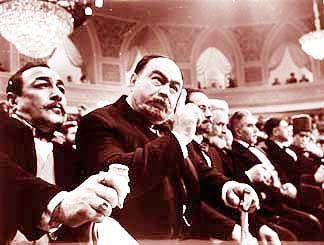

Left: From "26 Baku Commissars"

(26 Baku Komissary), 1966. Aghdar Ibrahimov directed the film.

The main figure (above) is Adil Iskandarov who plays Khachatorov.

The movie is about the dramatic revolutionary events in Baku

in 1918. Left: From "26 Baku Commissars"

(26 Baku Komissary), 1966. Aghdar Ibrahimov directed the film.

The main figure (above) is Adil Iskandarov who plays Khachatorov.

The movie is about the dramatic revolutionary events in Baku

in 1918.

Echoing Lenin, one of the leaders of Azerbaijan at that time

wrote: "In the East, where people are used to thinking mostly

in images, the cinema is the only possible means of propaganda

that doesn't need any preliminary preparation of the masses."

In July 1920, barely two and a half months after the Soviets

occupied Azerbaijan, a decree was made to nationalize the film

industry. This decision politicized the entire creative process

and severely limited the choice of topics. It meant that filmmakers

had to follow government policy.

One of the veterans of Azerbaijani cinema, film director Tofig

Taghizade, born in 1919, observed: "Before the Soviets came,

seven or eight entertaining films had already been produced.

They were mainly comedies and melodramas. Though I'd rather not

discuss their quality, one of them ("In the Realm of Oil

and Millions") was quite serious. But with the arrival of

new power, the Azerbaijani screen reflected the headlines of

newspapers-such as "The Parade of the 11th Red Army in Baku,"

"'The Funeral of the 26 Baku Commissars" and other

similar titles.

A whole series of films about the Revolution [of 1917] followed.

In addition, there were films about women's emancipation and

the struggle against religious fanaticism. These revolutionary

movies were based on the same pattern, variations on the same

theme. Always central to the plot were workers or peasants from

remote villages, full of class hatred toward their exploiters.

The landlords and capitalists were depicted as being evil and

were often satirized. There were no nuances in the description

of the heroes or events. The characters were like pawns on a

chessboard-whites on the one side, blacks on the other.

But at the beginning of the century, the truth is that Azerbaijani

peasants were so backward and uneducated that they didn't understand

the nuances of what "class struggle" meant. The same

was true of Azerbaijani workers. They were too occupied with

their own everyday, mundane problems to think about destroying

the foundations of society. So the characters in these revolutionary

movies were quite exaggerated. Without a doubt, they misrepresented

the reality of the period.

I don't want to condemn the creators of these films. Obviously,

they either believed in what they were doing or, perhaps, didn't

have any other choice. They were obliged to deal with the system

and yet try to make a positive contribution in it.

Filming Between

the Lines

When I asked Tofig Taghizade whether some filmmakers tried to

step outside these boundaries, he told me he didn't remember.

"The rules of the game were very cruel, especially after

Stalin's 1937 repression when hundreds of thousands of Soviet

citizens, many of whom were only suspected of resisting the government,

were hauled off to labor camps in Siberia. Most of them never

returned."

What freedom of speech could have existed in this environment?

Even "Arshin Mal Alan" (1945) risked being stopped.

Based on a comic opera (1910) by composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the

film was attacked because of its "bourgeoisie inclinations."

(The events take place in the homes of a landowner and a merchant.)

In fact, the plot is actually not about wealth but rather about

finding a bride to marry. The only reason the movie wasn't banned

was that Stalin liked it himself. In fact, he honored Hajibeyov

with the Stalin Prize for it, making him the first Azerbaijani

to receive such an award.

|

|

Left: From "Gold Precipice" (Gyzyl

Uchurum) 1980. Directed by Fikrat Aliyev. Scene at a restaurant

in Paris. Jalil with his mistress.

Right: From "Sevil," 1970. Directed

by Vladimir Goriket. Left, Sevil (Valentina Aslanova) is insulted

by Balash (Hasan Mammadov). Original film in 1928 challenged

women to take off their veils.

I, myself, experienced

a few incidents with censorship while preparing the movie, "On

Distant Shores." The film was about an Azerbaijani WW II

hero, a secret service agent named Mehdi Huseinzade. Since the

movie was based on a true story, the script was based on historical

facts and documents. But the movie was stopped in Moscow at the

very last moment. The censors didn't like the fact that the hero

was Azerbaijani. "Are you saying that some southerner from

Azerbaijan won the war against the Germans?" they pressed

me. I tried to persuade them of the truth of the events, but

they balked and didn't want to allow me to release the film.

I finally succeeded after contacting some influential people

that I knew personally.

Unfortunately, the destiny of all films from the 15 republics

was in the hands of Moscow censorship. To get film approval took

months, sometimes years. Everything was centralized. Films were

allowed to be shown only after the process of "purification

from ideological ambiguity." Even those movies which had

been made according to very high levels of professionalism were

not able to escape; often, realities were replaced by contrived

situations and events.

One famous Russian actor recently talked about his experiences

on a television interview. "It was the post-war years in

Russia. Life in the country was extremely hard. People were hungry,

almost everything had been destroyed. But we were making a film

showing happy faces as if life were a paradise. Once while we

were taking a break from filming, a local citizen, an old woman

dressed very shabbily, approached me. Looking at the expensive

shirt I was wearing, she asked, 'Whose life are you telling about?'

And I replied 'Ours.' And she looked at me and said, 'You're

too young, and, besides, you're lying,' and then she walked away."

A New Generation A New Generation

Photo: From "Last Mountain Pass"

(Akhirinji Ashirim) 1971. Directed by Kamil Rustambeyov. Left,

Hasan Mammadov as Abbasgulu bey with Hamlet Khanizade as Talybov.

During the "Khrushchev thaw" after the death of

Stalin, a new generation of filmmakers emerged. They were progressive-thinking

artists who resisted dogma. They included names like Magus and

Rustam Ibrahimbeyov, Rasim Ojagov, Anar, Eldar Guliyev, Ogtay

Mirgasimov and others. All of them had graduated from the Moscow

Institute of Cinematography.

In 1979, the steady, predictable course of Soviet cinema was

disrupted by a film called "Inquisition" (Rustam Ibrahimbeyov

and Rasim Ojagov). This landmark film was based on a psychological

drama. The hero, Seyfi, is an honest magistrate who looks for

evidence to prove that the responsibility for a certain crime

lies with the rulers of the society, somewhere in the government.

The plot develops to show that the man accused of committing

the crime is actually the victim of it himself.

Left: From "Interrogation" (Istintag), 1979.

Directed by Rasim Ojagov, screenplay by Rustam Ibrahimbeyov.

Elena Smitnova as Ayan. Left: From "Interrogation" (Istintag), 1979.

Directed by Rasim Ojagov, screenplay by Rustam Ibrahimbeyov.

Elena Smitnova as Ayan.

When the film appeared,

there was a huge uproar, not only in film circles but among the

general society as well, especially among party officials. The

regime wouldn't tolerate any ideological deviation, especially

one critical of the law. The creators of the film were trying

to penetrate this forbidden sphere. In their film, they challenged

a society that worshiped false values and who allowed a double

standard of moral and social justice to exist.

It was difficult to get permission

to screen the film. Naturally it was the Party representatives

who resisted the most, along with the office of "ideological

customs" in Moscow. But times were changing.

The opinion of Heydar Aliyev at the time proved very helpful:

"Let them know that there is corruption and bribing going

on in Azerbaijan. The more we hide it, the worse it will become."

Nevertheless, the film was forbidden in certain regions of the

USSR.

Rather ironically, "Inquisition" was awarded the top

prize at the 13th All-Union Film Festival in 1980. A year later

it won the USSR State Prize.

Today's Azerbaijani filmmakers continue the quest to present

reality as they understand it. As Rustam Ibrahimbeyov says, "there

have always been people who have felt the necessity of change

earlier than others. Such people are essential for society. Nothing

is more important than human initiative and the freedom to create...To

find and support such people is the great task of both literature

and art."

Asim Jalilov is a screenwriter and journalist living in Baku.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(5.3) Autumn 1997.

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 5.3 (Autumn 1997)

AI Home | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|