|

Autumn 1998 (6.3) "Mother-of-All-Books" by Anar

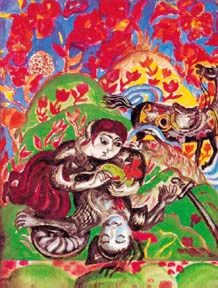

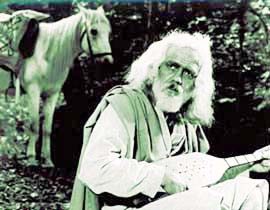

Every nation has at least one "mother-of-all-books," a work that reveals the identity, values and character of the people who live there. For example, there's the Odyssey and the Iliad (Greek), Kalevala (Finland), Shahnameh (Iran), Manas (Kyrgyzstan), Mahabharata and Ramayan (India), Igor (Russia), Song of Roland (France) and others. In each case, such a book illustrates the nation's struggles, rules and laws, as well as its spirit. It tells the nation's people where they came from. This book for Azerbaijan is the Dada Gorgud epic (or Dede Korkut, as it is sometimes spelled). For an Azeri to enter the world of Dada Gorgud means to enter ancient, yet familiar, territory. Its historical events, geographical names, tribal and family names and traditions are well-known to us. The book also raises questions for us about our language, words that are still in use as well as those which have since disappeared. However, with the exception of some bygone words and phrases, the language of "Dada Gorgud" is our native language, the language of the Azerbaijani Turks. The Book's Origins Turkish scholar Orkhan Shaig Koklay, who published a complete version of "Dada Gorgud," asserts that "the Azeri background is obvious in the Dresden version of the book." (He's referring to the "Dada Gorgud" manuscript now found in The Royal Library of Dresden. There is only one other known manuscript. It is in the Vatican library.) Unfortunately, there are no original manuscripts of Dada Gorgud in our own archives. Photo: Scene from Dada Gorgud. Mother tending her son who was unintentionally shot with an arrow by his father. Artist: T. Narimanbayov. The epic of Dada Gorgud is the most important proof that the Azerbaijani Turk nation has lived on its lands since ancient times. This is important to point out because there are still some people who doubt or, worse yet, deny this fact. As mentioned earlier, there is a close relationship between the language of the book and today's Azeri language. This proves the ancient connection of the Azerbaijani people to their land - they are not newcomers to this region. One of the most important questions related to this book, perhaps the most important one, is the question of its age. This matter relates to more than just literature. It relates to the question of when the tribes mentioned in the book first considered Azerbaijan to be their motherland. The text of the book shows that these tribes considered themselves to be the most ancient population on this land. Much of the book's material dates back to the time before Islam came to the region (7th century). Although the book itself may have been set down in written form at that time, its roots, some of its motifs, characters and story lines, plus the whole spirit of the epic, go back to ancient times. One piece of evidence is the references to the ancient Turkish god Tanri (heaven, sky) who is invoked, rather than the Muslim Allah. British scholar Geoffrey Lewis writes: "The history of this epic is very ancient. These works were created much before the rise of Islam and they express the lifestyle of nomadic Oguz" (Turkish tribes). Dada Gorgud's Role There is a measure of ambiguity in this title. Does it mean a book written by Dada Gorgud, or a book written about Dada Gorgud? Dada Gorgud is the book's narrator but he is also one of its main characters. As a sage and a storyteller, he seems to have lived longer than many of the people who are protagonists in his story. His most important function is at the end of each story where he makes a moral statement to summarize the plot. Dada Gorgud is not only an important character in the book - he is its primary author. Usually, "The Book of Dada Gorgud" is considered to be a collection of folklore. It makes more sense to talk about Dada Gorgud as the first creator of a written work in our literature. He took legends and characters that had been known since ancient times and adapted them for his own audiences. For example, in the eighth story there is a one-eyed figure named "Tapagoz" who bears great resemblance to the Cyclops of Greek mythology.

The stories are written in several different genres. For example, "Basat and Tapagoz" is a fairy tale about a one-eyed monster. "Dali Domrul," on the other hand, is more of a philosophical poem. The stories about Gazan Khan and Beyrak read like realistic novels. The parts dedicated to Bugaj, Imran, Yeynay and Seyray are shorter novellas. And the selection about rebellion within the tribes takes on the form of classical tragedy. Some of the stories are told so vividly that it's almost as if they were scenes from a movie. Take, for example, the book's first story, which tells about Bugaj, a young boy who goes hunting with his father, Dirsa Khan. Tricked by his advisors, the father shoots an arrow at his own son: "As the boy was hunting for a gazelle, he passed in front of his father. Dirsa Khan took out his bow - the bow that had been blessed by Gorgud - mounted his horse, aimed his arrow at the boy and shot it. The arrow hit the boy right between the shoulder blades and red blood started flowing. Bugaj grabbed his horse by the neck and fell to the ground." This scene is so cinematic that it's almost as if a film director already has his camera angles outlined for him. There's the initial wide-angle view of the boy hunting the gazelle. Then there's the shot of Dirsa Khan getting on his horse, preparing his bow, and shooting at his son. The camera follows the path of the arrow until it hits the boy; blood spurts from the wound. In the final shot, the boy wraps his arms around his horse and collapses to the ground. When Bugaj doesn't return, his mother starts to worry and goes to look for him: "She reaches Gazilig mountain, so cold that its ice never melts...She sees a black raven fly to that mountain, sit there, then rise again. Bugaj's mother pulls the bridles of her horse and moves toward that place." This image of the worried mother looking up at the raven and the mountains is a classical cinema shot. It turns out that the boy is severely wounded, but not dead. The raven sees the spilled blood and wants to land on Bugaj, but the boy's two dogs protect him. Bugaj's mother rescues him, and he is eventually reconciled with his father. Memorable Characters Beyrak exhibits many other human qualities. He is unselfish. When he helps some merchants escape from an attack, he leaves without taking any gifts in return-he doesn't even mention his name. Beyrak is loyal to his friends, willing to give away his last shirt to help them. He's also loyal to his bride-to-be. While in prison, he resists the advances of another woman. He's also a bit boastful, as is shown when he shows off at another man's wedding. In the last story, Beyrak is killed by his father-in-law because he would not join the rebellion against his khan. He remains a loyal subject even unto death. Treachery is a persistent theme in "Dada Gorgud." Especially tragic is the story of infighting within the tribes, as friends fight friends and nephews fight uncles. Beyrak's fate is recalled in Dada Gorgud's mournful benediction to the story: "Where are the valiant princes? Where are those who say that this world is mine? Fate took some of them, the soil hid some. Who is this empty world for? The world to which men come and leave, the world whose latter end is death? Welfare, old age, everything ends with death, everything ends with parting." But in the midst of all this tragedy, Dada Gorgud concludes his stories with hopeful blessings. For instance, at the end of the first story, he says: "Let your mountains live, strong and black! Let your lakes be full of water, let your trees be green! Let your horse always be good for you! May hope always be with you! May you have wings to fly! May you always have fire and warmth for your house!" Dada Gorgud's words, Dada Gorgud's conversations, Dada Gorgud's blessings which have come down through the centuries and millennia are even more important for us today - more valuable than ever. Anar, President of the Writer's Union, is one of Azerbaijan's most profound and recognized writers. He is especially familiar with the stories and themes of Dada Gorgud having written the screenplay for film (1975) and written a book about the topic (Moscow, 1988). From Azerbaijan International (6.3) Autumn 1998. Back to Index

AI 6.3 (Autumn 1998) |