|

Winter

1998 (6.4)

Pages

24-28

The Metamorphosis

of Architecture

and Urban Development in Azerbaijan

by Pirouz Khanlou

The

state of architecture in Azerbaijan today is one of dramatic

change and transition. Here architect Pirouz Khanlou describes

the path that architecture has taken throughout this past century

and where it is headed. The purpose of this article is not to

elaborate the history of Azerbaijan's architecture, but rather

to discuss its transformation and define some of its current

needs and problems. The

state of architecture in Azerbaijan today is one of dramatic

change and transition. Here architect Pirouz Khanlou describes

the path that architecture has taken throughout this past century

and where it is headed. The purpose of this article is not to

elaborate the history of Azerbaijan's architecture, but rather

to discuss its transformation and define some of its current

needs and problems.

How do you embrace

the future without discarding the past? This question brings

to mind the figure of the Roman god Janus, an astute personage

who is always pictured with two faces, looking forward and backward

at the same time. The month of January was named after this god

because he was identified with beginnings. Newly independent

countries like Azerbaijan need to adopt both profiles just like

Janus, as they look ahead to the prospect of the future while

at the same time not forgetting their past. The question is how

to transition to a free market economy while remaining integrated

within the cultural and historical framework of the past.

As an architect, I wonder how Azerbaijan will face the future

and its challenges and yet protect its own rich cultural and

architectural heritage. For instance, will it be able to preserve

the exotic medieval Inner City (Ichari Shahar) and Baku's 19th-

and early 20th-century center, which fuse a variety of European

styles (Neo-classical, German and Italian Renaissance Revival,

French Gothic, Art Nouveau) with Eastern styles (Safavid, Persian,

Cairo, Ottoman and Magrebi)?

Being the capital city, it is Baku that becomes the model for

the rest of Azerbaijan. Baku is perhaps the only true Eurasian

city on the world map, not only geographically but in its unique

ability to synthesize both European and Asian architectural styles

which are indicative of the mental synthesis that has taken place

in cultural and social realms as well. This uniqueness must be

maintained and fostered.

|

|

Left: The residence of the Sadigov Brothers

is one of many eclectic buildings based on an eclectic style

in central Baku. Here a French Islamic Magrebi style presents

an interesting design solution for a corner building. Architect:

Ter Mikelov (1911).

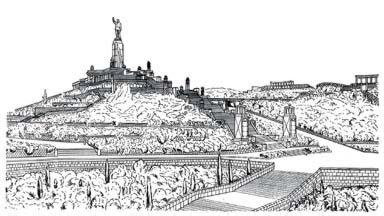

Right: Perspective of Kirov Monument at Baku's

summit (1951). It resembles an ambitious Stalinist Fascist architecture

with its grandiose scale overlooking the city. Kirov's statue

was pulled down when Azerbaijan gained its independence (1991).

Architect: L. Elin. |

Oil Boom

The turn-of-the-century Oil Boom triggered a "Big Bang"

in the architectural history of Baku. Before this time, Baku

had been only a sleepy little town that did not play a major

role in the region, especially compared to Tabriz (now Iran),

Tbilisi (now Georgia) and Istanbul (Turkey). Beginning in the

1880s, however, hundreds of new buildings and residences were

constructed, each more extravagant than the next, as Oil Barons

competed with one another to see who could create the most spectacular

building.

By the early 1900s, Baku had become a fully developed, sophisticated

metropolitan center in the Caucasus. Based on a well-planned

urban design, its municipal infrastructure included parks, streets,

public transportation, along with a safe water supply, sewage

and railway systems. There were numerous public buildings such

as schools, hospitals, opera and drama theaters, government buildings,

mosques and cathedrals. Perhaps most noteworthy were the elegant

private residences built by the oil barons. Baku's existing downtown

is a brilliant manifestation of this period. The industrial district

on the north side of Baku, familiarly known as "Black City"

(Gara Shahar), was characterized by the state-of-the-art petroleum

industry of its time, and included industrial buildings, refineries,

exploration facilities, a related manufacturing and transportation

system as well as housing for the workers.

The Oil Boom, based on private ownership and entrepreneurship,

came to a screeching halt when the Bolsheviks toppled the Democratic

Republic of Azerbaijan and took over Baku (April 1920). Thus

began a completely new era in the history of the country, affecting

every aspect of political, economic and social life, including

architecture. The luxurious residences of the oil barons and

other industrialists were seized and all personal belongings

were confiscated. Except for the grandest of buildings, mansions

were partitioned into apartments and assigned to numerous families.

The glory of the past was reduced to "communal dwellings."

Left: General view of industrial

developmentBalakhani in the "Black City" of Baku

of early 20th century.

Right: Yesterday's dream (1963): a socialist

mass housing development in Micro Region No. 1, Baku. Today's

reality: poorly maintained apartment complexes. Ganjlik region,

Baku.

|

|

Soviet Planning

The

decade between 1920 and 1930 could be called the "Decade

of Transition". Russian intellectuals and the avant-garde

were excited about the Socialist Revolution and were in search

of a New Soviet Man and a socialist society. Naturally, these

mainstream revolutionary movements influenced the new Soviet

Republic of Azerbaijan. At this time, New Economic Planning (NEP)

was implemented. City planning was organized primarily by Moscow,

and local architects and urban planners were influenced by Modernists

such as Le Corubsier (projects like "unit d'habitation")

and especially Constructivists like Moises Ginsburg.

Between the 1930s and mid-1950s, Baku, like many other Soviet

cities, was given a Master Plan. This period can be categorized

as the Stalinist period, during which large-scale buildings of

solid quality and construction were erected. Many public buildings

and infrastructure projects were undertaken at this time such

as the Ministries building and numerous apartment buildings.

Many of these housing projects were based on typical socialist

planning in which the massing was organized around communal gardens.

Between the late 1950s and the mid-1980s, there was a special

emphasis on housing. Many large-scale housing projects were completed

in Baku and other Azerbaijani cities. They were characterized

by central socialist urban planning under the concept of "Ideal

Communist City Planning." Micro-regions (suburbia) and satellite

cities such as Sumgayit were built in Baku's outer limits. In

general, this period is marked by large-scale mass housing projects,

wide avenues, standardization of building design and construction

method and the introduction of prefabricated construction elements.

These projects reflect the era in which they were designed and

constructed-such as the Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev periods.

Left: Azerbaijan International Bank and ISR

Plaza adjacent Fountain Square which have just been completed.

Right: An example of poor eclectic design

which has no relevance to its context in downtown Baku. Caricature

of Persian architecture.

Collapse Collapse

From

the early 1980s until the collapse of the Soviet Union in late

1991, the Soviet bureaucracy, crippled by an economy that was

nearly bankrupt, proved incapable of continuing its ambitious

city planning and urban development projects. Tragically, it

could not even maintain its existing buildings and aging infrastructure.

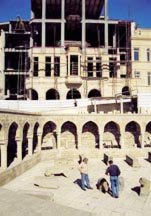

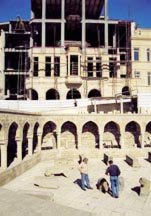

Photo: New development in the "Inner

City" behind a medieval courtyard.

A primary reason for this collapse was that Soviet technology

had become hopelessly outdated. The West, spurred to sudden growth

by developments in the computer industry, went through what amounted

to a second industrial revolution, whereas the Soviet Union fell

behind. Soviet products could no longer compete on the world

market because they were built with technology from the 1970s.

Huge Azerbaijani factories such as the ones in Sumgayit became

good for nothing more than scrap metal.

The Perestroika and Glasnost phases of the Gorbachev era played

an important role in opening up the Soviet Union to the outside

world. In September 1990, the SSR Azerbaijan hosted the First

Azerbaijani Business Congress in Baku, attracting several hundred

business representatives, companies and entrepreneurs from all

over the world. For the first time since the collapse of the

Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan (1920), this marked an independent

effort by Azerbaijanis to connect to the outside world. It is

interesting to look back now and realize that many of these same

businessmen have returned to Azerbaijan to initiate new projects

and bring foreign investment to the country.

|

|

Left: Azerbaijan

Press House influenced by Constructivist architecture style.by

S. Pen (1934).

Right: Constructivist design

proposal for a cultural center in the Bailov region. Architect:

L. Vesnins (1937). |

New Momentum

In 1994

with the signing of the "Contract of the Century,"

as Azerbaijanis dub the contract with AIOC, a new stage of development

for Azerbaijani business began. As Western oil companies began

to establish offices in Baku, there was an urgent need for modern

strategic service industries such as telecommunications, transportation,

banking, insurance and hotels. It became crucial to make the

country "business-able." Since late 1995, many major

commercial and residential construction projects have been initiated.

Some have already been completed, while others are still under

construction. This renewed development is somewhat reminiscent

of the Oil Boom of the late 1800s-after nearly 80 years, a new

energy is being pumped into the architectural development of

the country.

For the most

part, construction and development has been so rapid that legislation

has not been able to keep pace, especially in terms of municipal

ordinances such as city zoning and building codes (regulations),

and the establishment of various architectural commissions and

other appropriate governing bodies. The Soviet regulations of

the past no longer apply or fulfill the needs of the present

day, and new laws have yet to take their place. There are no

systematic rules and regulations that apply to modern construction

technology or fulfill present needs for contemporary building

and development.

Right now with the new privatization, rules and regulations are

interpreted individually. To prevent this, Baku city needs to

have a working plan-checking system, clear zoning definitions

and a building inspection system that is fairly and correctly

implemented.

This is a determining moment in Azerbaijan's history. So many

changes are going on that the transformation seems quite overwhelming.

Baku was not designed to handle this much growth. At the same

time, it cannot inhibit growth, nor should it. It is time to

deal seriously with these issues so that Baku's appearance will

be protected and the health, environment, safety and well-being

of its entire population will be guaranteed.

|

|

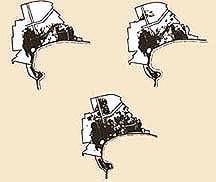

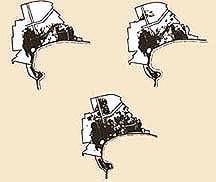

Baku in 1806. 1822. 1854. 1878 |

1898. 1918. After 1918 |

A Master Plan

Baku

needs a revised Master Plan. The most recent one was introduced

in 1984 after 12 years of deliberation. It was supposed to be

completed by 2005, but quickly became outdated in 1991 when Azerbaijan

began its path from a centralized state economy to a market economy.

An independent country with a new governmental structure and

a new privatized market economy requires a service sector, including

banking, insurance, transportation, shipping, airports, terminals,

business and commercial projects, housing and mixed-use developments.

This infrastructure requires many new buildings: hotels and restaurants

for the tourism industry, shopping centers, business centers,

communication centers, sports facilities, conference centers,

etc.

A new Master Plan must address the needs of a market-based society,

especially needs created by economic and population growth. For

example, in Baku there are still no guidelines in place regarding

parking requirements in new buildings, not even high rise buildings.

The concept of parking inside a building is still so new that

one city building official recently told a foreign developer

that it was dangerous for cars to be parked in garages underneath

the building! With the recent multiplication of cars in Baku,

traffic and parking is already an issue, and will soon become

a more serious problem.

Petroleum

office building influenced by the modern movement (1952). Petroleum

office building influenced by the modern movement (1952).

Internal Refugees

The tragic displacement of nearly one million internal refugees

due to Armenia's occupation of close to 20 percent of Azerbaijan's

territory has exacerbated the situation. Baku alone has seen

an influx of 200,000 to 300,000 refugees, stretching the city's

infrastructure beyond its capability. Ten years ago, the population

of Baku was less than 1.5 million; today it is closer to 2 million.

In addition to the fact that these people need jobs, the strain

on public services is unprecedented.

Nearly every

section of the city, some more frequently than others, has to

cope with the sudden interruption of utilities, whether it be

water, gas or electricity. This is the norm rather than the exception.

There are immense plumbing problems as faucets run and cannot

be shut off. The city's sewage system was not built to handle

its present load. Streets are in disrepair and filled with treacherous

potholes. Telephones are still far from adequate, even though

immense improvement has taken place since 1995.

Left: General view of industrial development - Balakhani

in the "Black City" of Baku of early 20th century. Left: General view of industrial development - Balakhani

in the "Black City" of Baku of early 20th century.

Zoning

Well-thought-out

zoning codes need to be studied and implemented so that they

will regulate commercial, high-density and low-density residential

areas as well as hospitals, schools and agricultural areas in

an appropriate manner. For example, in the Inner City, office

buildings and companies have already invaded a historic residential

area.

Building Codes

Well-developed, modern building codes and regulations need to

be implemented along with a fair but strict inspection system.

Currently, there is no systematic plan-checking protocol that

guarantees that building codes and regulations are followed before

a building permit is issued. Outdated Soviet-era building codes

don't take into account appropriate building safety requirements

or new kinds of construction technology.

Transportation

Baku

needs a safe, reliable transportation system that incorporates

public transportation such as the Metro, tram and bus systems

as well as private vehicles. In 1995, the worst Metro accident

in world history took place in Baku when a fire broke out in

a subway car during rush hour. More than 300 people lost their

lives in the nightmarish scenario that followed, as passengers

were trapped and suffocated in the train cars. Other aspects

of the city's public transportation system are also in desperate

need of repair. Buses are dilapidated and need maintenance. Tram

cables often slip off of their electric wires, resulting in traffic

jams and delays. These systems need to be studied and updated

and put on regular maintenance programs.

Traffic

Traffic

patterns need to be studied and systematized. Baku was planned

during the Soviet period when private ownership of cars was rare.

Most people relied upon public transportation, as ownership of

cars was restricted to government officials and extremely privileged

Party members. These days, however, cars are widely available.

During the past five years, the private use of cars in Baku has

increased at least twenty-fold. Consequently, the desperately

outdated traffic system does not work anymore.

For example, there is no system for making left turns or U-turns

in the city. Instead, one has to drive to a roundabout that may

be miles away. Most city streets are based on a one-way system,

but not in a consistent, predictable pattern of alternating streets.

There is an enormous amount of redundant traffic movement, which

results in street congestion, pollution, wear and tear on the

streets and vehicles as well as waste of fuel-not to mention

the amount of time that is lost. This is especially true in central

Baku and the Inner City.

Historical Buildings

Azerbaijanis

also need to have a better understanding of the architectural

structure of their historical buildings. In many old buildings,

columns are three feet or more in diameter. There have been occasions

when contractors thought that they could hack away at the outside

of the column to decrease its size, not realizing that the strength

of the column is in its outer concrete rim, not in the center,

which is usually filled with loose debris and rubble. Such ignorance

can cause entire buildings to collapse. Not long ago, a column

in one old building was removed, causing the entire building

to collapse into tons of debris.

Conservation

Conservation

and renovation regulations should be passed and strictly enforced;

otherwise, the beauty and uniqueness of many of Baku's older

buildings will be at risk. Of course, this threat is nothing

new, as the Soviets were notorious for dividing beautiful mansions

into numerous one- and two-room apartments, giving residents

no choice but to share kitchen and bathroom facilities.

Inner City (Ichari

Shahar)

The

development going on in the Inner City should be re-examined.

The narrow lanes and alleys of the Inner City were primarily

designed for pedestrian use. In a few places, camel caravans

and horses could navigate the area. Now, because of a lack of

zoning regulations, nearly a dozen international companies have

moved their offices inside the 12th-century citadel walls, simply

because management was intrigued by the exotic location. As a

result, there are frequent traffic jams.

First, the Inner City should be preserved to maintain the pulse

of the vibrant residential community that has lived there for

many generations. Large corporate offices should not be allowed

in the central part of town. Second, the outer edges of the Inner

City should be developed to attract tourists with gift shops,

restaurants and other sites. Of course, there are many gray areas

when it comes to conserving buildings. Inevitably change will

and should result simply because building materials are different

today from what they were 100 years ago.

Training of Architects

Today's

architects, planners and engineers need to be trained for the

future. Azerbaijanis are at an extreme disadvantage, as their

knowledge has become obsolete. Examples such as the unfinished

Baku airport (Bina) and the old Moscow and Karabakh hotels illustrate

that local architects don't understand the basic principles of

airport and hotel design.

Architects need to be retrained. Exposure to the outside world

is essential. Architecture schools in Azerbaijan would benefit

tremendously from new curricula, architecture books and journals,

exchange programs, seminars, visiting professors and relationships

with international institutes. Students need exposure to architecture

in other countries, which of course means traveling there. Architects

also need to have exposure to the latest concepts set forth in

international architectural books and journals.

Personal Responsibility

So far,

I've discussed issues that must be implemented on a governmental

level. Now I would like to mention the necessity of adopting

a new mental attitude. With personal ownership comes the necessity

of personal responsibility. In the past, Azerbaijanis took care

of the interiors of their apartments, assuming that the government

would maintain the exterior. In other words, they compartmentalized

ownership between the individual and the state. If something

belonged to the state, they ignored it, or even abused it. This

kind of mentality has to change.

In a market-based

society, communities come together to make decisions about how

their environment should look and be maintained. Azerbaijanis

are still struggling with this concept. For even a simple decision

like maintaining a public stairwell in an apartment building,

neighbors are still floundering, not knowing how to organize

themselves to agree upon a plan of action. Individuals must learn

to participate in the decision-making process, and not just assume

that someone else will take responsibility for the things that

need to be done.

Mechanisms need

to be created to incorporate input from the community into the

existing environment. In this way, systems can correct themselves,

and development can move ahead. Problems that we can't anticipate

today will be handled wisely and in due course if there is a

systematic framework for addressing them.

From Azerbaijan

International

(6.4) Winter 1998.

© Azerbaijan International 1998. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 6.4 (Winter 1998)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|