|

Spring

1999 (7.1)

Pages

72-73

Independence

(1991-present)

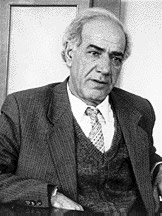

Sabir Ahmadli

(1930)

Voice From the Sea Voice From the Sea

(February

1990)

At midnight

on the eve of January 20, 1990, Soviet troops entered Baku and

attacked from all directions, including the sea. It was an unprecedented

attack by Soviet troops on unarmed citizens in Soviet Azerbaijan,

and it sent shock waves throughout the Republic (See "The

Russian Bear's Voracious Appetite," AI 3.1, Spring 1995). Azerbaijanis

now refer to it "Black

January".

There had been earlier attacks in other Soviet Republics but

never on the scale that took place in Azerbaijan. In 1986, Soviet

tanks attacked Almatai, Kazakhstan, and two people allegedly

died. In April 1989, an attack was made on Tbilisi, Georgia,

with official deaths stated at 16.

But in Baku under the pretense of "restoring order to the

city," the Soviet army entered the city and brutally attempted

to squelch the independence movement, which had been gaining

momentum. They mowed down everything in sight with their tanks

and submachine guns.

Peaceful demonstrators were shot in the streets. Tanks crushed

cars loaded with passengers still inside. A nine-year-old child

and her father, returning from a wedding, were shot while riding

the bus home. Even people looking out of apartment windows and

balconies were shot and killed. Unbelievably, soldiers opened

fire on ambulances.

Officially, 132 people died that night, but Azerbaijanis suspect

that the number was drastically underreported, perhaps by several

hundred. Nobody really knows how many victims died in "Black

January." Corpses were gathered before daybreak and hauled

off to ships until they could be dumped at sea.

Azerbaijanis, though still under Soviet rule, went into shock

and mourned for 40 days. The city was draped in black. Windows

and balconies were covered with black material; black strips

of cloth were tied to windows, car antennas and trees. Adults

boycotted their workplaces; children stayed home from school.

The nation writhed in pain-in essence, these were the labor pains

that would give birth to a new independent Republic. Even staunch

communists burned their Party membership cards openly.

Sabir

Ahmadli,

who was honored as an Azerbaijani People's Writer during the

Soviet period, heroically dared to publish the first literary

short stories about this crisis, even though the dissolution

of the Soviet Union would not take place for another 18 months.

This collection of short stories first appeared in the monthly

magazine "Adabiyyat" (Literature) and came out as a

collection of 20 short stories in "January Stories"

(Yanvar Hekayalari, Baku, 1992, 125 pages in Azeri Cyrillic).

Ahmadli's style could be described as surreal. In "Voice

From the Sea," a son, murdered on that chaotic night, describes

the events that surrounded his death as if he were writing his

mother a letter. All the while, his corpse, which had been disposed

of in the sea, floats around, bumped by seals.

_____

Dear

Mother,

First of all, hello. In case you're wondering about me, well,

I'm not so very far from Baku. I'm near the city of Darband.

1

The weather is cloudy and rainy. But don't worry, I'm not cold

at all. It's snowing at sea, but that makes no difference to

me. I'm not alone here, Momma.

It would be better if I told you everything just like it happened.

I know you haven't been able to sleep or rest. I know you've

been searching for me in all the hospitals and morgues in the

city. Not a single son would dare tell his mother the agonies

that I'm going to tell you. But I want you to know everything.

One moment...Oh, oh!

On the night of January 19th, that disastrous night, remember

how you didn't want to let me go out of the house? I tried to

reassure you that there was no need to be afraid, as I would

be with friends and they would feel hurt if I didn't go out with

them.

We were walking down Tbilisi Avenue, somewhere near Bilajari

Heights, when the army started attacking the city. We were among

the first to see the troops. Tanks descended on us. None of us

could understand what was happening. We thought they were simply

trying to frighten us-that once they reached us, they would stop.

The bullets of the soldiers streaming after the tanks seems to

be just flares...

One moment...Oh, oh! There are so many seals in the sea, Mother!

One just passed by, swimming towards another body.

Yes, mommy dear! A lot of young boys around me were killed. I

couldn't believe it. It was only when the bullets seared my own

chest that I began to understand. The tanks moved ahead, sub-machine

guns blasting steadily, mowing everyone down. Then more armored

vehicles appeared in the streets. The electricity suddenly went

out, leaving the carnage in total darkness. What was going on?

What had happened to my friends? I raised my head to see if I

could find them.

Left: Tens of thousands of people gathered

in Lenin (now Freedom) Square to attend the funeral of the victims

of Black January 20 (1990). Left: Tens of thousands of people gathered

in Lenin (now Freedom) Square to attend the funeral of the victims

of Black January 20 (1990).

Ambulances stopped nearby. Soldiers got out and  began

gathering the bodies that were lying in the road. There were

dark, bearded men among them. They were wild and frantic. They

began searching through all the shrubs and bushes. Whenever they

discovered anyone lying on the ground, they fired their pistols

and sub-machine guns again, killing those who had only been wounded

and making sure the dead ones were really dead. began

gathering the bodies that were lying in the road. There were

dark, bearded men among them. They were wild and frantic. They

began searching through all the shrubs and bushes. Whenever they

discovered anyone lying on the ground, they fired their pistols

and sub-machine guns again, killing those who had only been wounded

and making sure the dead ones were really dead.

I heard their voices, "Bistro ubrat! Chtobi do utra nichego

ne ostalos! Chisto!" (In Russian, "Take them away quickly!

Don't leave any evidence for the morning! Clear it away!")

They swept down and gathered us up, piling us inside the covered

vans and moving on. I didn't know our whereabouts in the city,

though I could tell that we were heading down towards the docks.

Military helicopters circled above. Two tankers were anchored

nearby the bridge. Other military vehicles followed us. Their

"freight" was being transferred to the ships immediately

in order to make way for more vehicles that followed.

Mother, one momentso many seals are swimming around me here in

the sea!

They took us aboard the Hydrograph tanker. The plan had been

highly masterminded. This time they had stretchers. Again they

checked us, shining lights into our faces, right into our eyes.

Bending down, they tried to find out if any of us were still

breathing, but they rarely fired their pistols, as they didn't

want to attract attention. They were saving their bullets. Seagulls

were flying all around. On board, they covered us with canvas.

Many of us were tied with rope and carried down into the cargohold

of the ship.

The ship moved away from the pier. It was already dawn. They

knew they had to leave, but they didn't know where to go; they

started getting worried. The Caspian Coast Guard was not allowing

the military ships to leave the bay. Oil tankers cut off their

escape and blockaded the bay. They began communicating by radio.

We could hear everything from where we lay in the icy, steel

hold. We could hear the Soviet military forces ordering the Caspian

Coast Guard to open the way immediately.

But they refused, insisting that they must inspect the ships.

"What are you taking away?" they demanded.

"We're taking the families of our military men," came

the reply. But the Caspians insisted on checking the military

ships before they would allow a single one to leave the bay.

For three days, the Caspians held the military ships at port,

not allowing them to enter the open sea. On the third day, a

special Deputy Commission arrived and came out to the "Sabit

Orujov" tanker 2 where we were being

kept. Even the Commission wasn't allowed to check the military

ships that moved in closer, threatening our ship. "If you

don't open an exit, we'll open fire!"

The Caspians stood determinedly, "Your ships are full of

corpses. During the night, when the army burst into the city,

you carried those you murdered down to the piers. Now, you want

to cover every trace of your crime." The gun turrets of

the military ships took aim at the Caspian ships.

On the morning of January 22nd (the third day) all the Caspian

ships began blasting their horns. Their bleak mournful cries

could be heard throughout the entire city. That's when they were

burying the victims, Mother! The words of the Koran were being

read. The voices penetrated even into the prison holds of the

ships. On hearing that the victims of this event were to be buried

up on the hill overlooking the city, someone mumbled, "If

we could only be buried there, too, I wouldn't complain."

The fourth day, the military ship opened fire on the Caspian

ships. Our ships answered. But the civilian ships could not withstand

the torpedo attack. Holes appeared in many tankers; some of them

caught fire. The blockade had been broken.

Our tanker headed out to the open seabut wait, Mother, one moment.

Be patient, Mother, oh, how many seals there are in this sea!

Even white ones...3

We sailed all night. At dawn, the ship's cranes began their work,

lifting the cargo out of the holds. The bundles were carried

to the edge of the boat. "Raz! Dva! Vzyali!" (One,

two, heave away!) and the corpses were thrown into the sea. Afterward,

body parts-arms, legs, heads-followed.

It was great torture! As if it wasn't enough what they had done

to us, in addition to kicking us and shouting, "Vot vam

Shahidlar Khiyabani!" (Here's your "Avenue of the Martyrs!")

Then we saw helicopters circling above us, Mother. Had they come

to help us? They swooped down nearly touching the waves. Their

doors opened and more men were pushed into the sea. They had

no parachutes and so they soon disappeared into the waves, never

to reappear. Oh, they weren't men of airborne troops, they were

ours. But they were brought by helicopters. Mother, it was if

the entire sea had turned into a vast graveyard, from Astrakhan

in the north to Lankaran in the south.

My dearly beloved Mother! Do you remember, one evening my sisters,

you, and auntie from the neighborhood were sitting with us? It

was spring; our exams had already begun. I told you my wish.

I told you how I wanted to go to Odessa and enter the Sea Academy.

You didn't approve. "You must stay beside me, my sweet one,"

you had told me. "You're the only brother of five sisters,

you are the only man of our house."

Now look at my fortune, Mother. It's the first time I've acted

against your wishes. Now I'm a sailor, Mother; I'm sailing. We

sailed for five days, then we were thrown into the sea. Some

in Shah-dili, others in Turkan, not far from Baku. You know the

sea doesn't keep corpses; it always washes them ashore.

The Turkan fishermen saw them. The villagers understood. The

fishermen surrounded us with their boats. But the coast guard

cutters were keeping close watch. The fishermen and the things

they saw just disappeared.

Just one moment. Oh, how many seals are here in the sea!

It is snowing here at sea. Spring is coming. Snow is falling

on my head. It's very stormy near Darband. But neither snow nor

wind can hurt us. The waves can't drown us, nor can the hurricane

silence our voices.

Along the cliffs, the Darband lighthouse shines brightly. I'm

sailing towards the shore embraced by the waves. If God so permits,

the citizens of this old Azerbaijani city will see me and if

they do, I know they'll save me.

Kiss my sisters, don't wait for me.

Your sailor son,

February 1, 1990

Footnotes:

1 Darband, an ancient Azerbaijani city where many

Azerbaijanis still live, is located north of Azerbaijan's present

border in the Russian Federation of Dagestan. Up

2

The "Sabit Orujov" is the triple-decker ocean liner

that served as the headquarters for the Caspian Coast Guard.

It was so heavily damaged during the January 1990 events that

it is no longer considered seaworthy and lies anchored at shore

next to the Terminal Port across from the Absheron Hotel where

it has been converted into a restaurant and bar.Up

3

White seals are a rare kind of seal in the Caspian Sea. Up

Translated

by Zeydulla Aghayev

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.1) Spring 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.1 (Spring 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|