|

Spring

1999 (7.1)

Page

76

Independence

(1991-present)

Saday Budagli

(1955- )

The Scoundrel

(1995)

"Nutty Salman," as some of his friends used to call

him, was pretty inept in life. Even though he felt so helpless

when others took advantage of him, one day he decided to say

and do exactly what he thought, with unprecedented results.This

story deals with the issue of rampant corruption in the society.

At

first, he used to just grumble a lot, complaining that we didn't

help him. That we didn't act like normal human beings. That other

storekeepers had people who delivered the goods to be sold. That

other storekeepers hired sales clerks to work at their stores. At

first, he used to just grumble a lot, complaining that we didn't

help him. That we didn't act like normal human beings. That other

storekeepers had people who delivered the goods to be sold. That

other storekeepers hired sales clerks to work at their stores.

He complained that he couldn't leave the store and had to close

it every time he went to get more goods. And if he did that,

he would have to carry the goods inside and then back outside

again for display.

Next he tried a different approach. "It's not my business,"

he said. "I earn enough to make a living. I'm just saying

this for your own good, you miserable ones. Don't you think it

would be better if you helped me and made some money instead

of just hanging around wasting your time? At least you'd have

money to buy cigarettes."

Photo: Saday Budagli

What's

the meaning of living any more? Are you going to find a son again?

Get married? Settle down? Why don't you just die, man!

Saday Budagli

(Addressed to an old refugee man, who was found dead a few days

later)

Finally, he started to hassle us. "It's your own business,"

he would say. "If you don't want to come, then don't. You're

not going to harm me by not coming. Sure, it's winter now, there's

no glass in the windows and the floor is bare concrete. But things

won't always be like this. They'll change as time goes by. Even

if they don't change now, there's still spring and summer. I'll

even put a fold-out bed here so you can stay here at night. Then

you can always gather here, fawning upon me and treating me nicely.

Don't worry-I'll find the appropriate thing to say to you at

that time."

I was one of those he accused of not acting like a "normal

human being." The only day I was free to go there was on

Sundays. Even then, if something else came up, I didn't go. Besides,

it had to be nice weather-it was impossible to be there during

cold weather. But soon, summer would come, and it wouldn't be

so bad to earn some money during my two months of vacation, just

like Salman had suggested. And the idea of getting away from

home sounded great.

That's why I didn't pay attention to Salman's rude words. I kept

my silence and when he insisted that I come, I muttered that

I didn't have enough time for my homework.

Salman had a ready answer. "If you studied hard, I wouldn't

even ask you to come  here.

But I know you. You don't want to work at all. If a person thinks

about tomorrow, then he needs to work, to wake up a bit early

and go to bed a bit late. You're spoiled: you've gotten used

to being supported by your parents. They feed you, give you a

little spending money, and so you pass your days this way. If

you continue this way, what will your future be? Do you think

that after graduating, the university will change you into another

person? Don't fool yourself. You're a bum here.

But I know you. You don't want to work at all. If a person thinks

about tomorrow, then he needs to work, to wake up a bit early

and go to bed a bit late. You're spoiled: you've gotten used

to being supported by your parents. They feed you, give you a

little spending money, and so you pass your days this way. If

you continue this way, what will your future be? Do you think

that after graduating, the university will change you into another

person? Don't fool yourself. You're a bum  now,

and after graduating, you'll become a now,

and after graduating, you'll become a

scoundrel."

Later, we laughed among ourselves at Salman's words. We even

chose a nickname for him-"Nutty Salman." When he wanted

to volunteer for the Karabakh war, my aunt went crazy, pretending

that she had become really sick, trying to make him change his

mind. But we considered Salman a hero. After five or six months,

he was wounded at the front and sent back to recuperate. He was

in the hospital for a while. Then my aunt prepared some papers

and managed to get some land for the store.

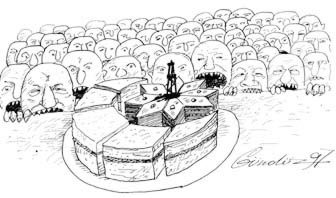

Sketch: Masses Greedy for Benefits

of Oil - Gunduz 1997

When Salman got out of the hospital, we were eager to hear about

his memories of the war, even more than seeing him. But it was

as if that bullet wound had made him lose his memory. He didn't

talk about the war. Whenever we insisted, he used to get angry

and say: "If you want to know about the war so much, then

why don't you go and see for yourself. Nobody is keeping you

here. Go and see it with your own eyes."

Even though his store was next to the bazaar, it wasn't very

visible and didn't do well. "It doesn't matter," said

Salman. "If one has good quality and sells it a little cheaper

than others, then he'll have so many customers that he won't

even have time to sit down and rest."

He made plans for his store, but they all required money. If

he could just save some more money, he would buy glass for the

windows, have the floor tiled and ask someone to make shelves

for the goods. He would buy a refrigerator, an air conditioner

and a tolerable car for transporting goods. But those things

were difficult to get for the time being; he needed some more

time.

The main thing was to put the store in order and hire a salesman.

Then the place would become a real store and he would be a real

merchant. He would have enough money to procure goods for sale,

and his salesman would be busy selling them. Then he wouldn't

need mongrels like us hanging around.

But there were people who prevented Salman from achieving his

plans and schemes. After each of their organized "attacks"

on the store to take money or something else, he forgot the words

that he had said only a day or two earlier.

He used to swear at the store and at the person who had given

him their story. "What kind of life is this?" he would

say. "Let one or two come, but everybody seems to come to

my store and act as if I owe their fathers something. It's as

if I owned a bank. If I had made enough money, I would have put

the store in order. But I'm spending my entire day here making

very little money." He was talking behind their backs mostly,

but when he was face to face with them, he wouldn't say anything

and would try to accommodate them somehow.

"What can I do?" he would say. "I have no other

choice. They can do anything to me. If they set a newspaper on

fire and tossed it inside the store some night, what could I

do? Who would I complain to?"

There were also those who used to come to the store for just

a loaf of bread. Salman was never angry with them. He gave money

to some and goods to others.

We got used to Feyzi Kishi.1 He was a short, thin man

between 60 and 65 years old. He wore an army cap and jacket.

He used to come and stand silently near the electric heater.

Sometimes he would eat lunch with Salman. Feyzi Kishi was a refugee

from Karabakh. He had lost his entire family-his son, daughter-in-law

and two grandchildren-in the war. He used to spend his day in

the bazaar. He would bring water for one, carry goods for another.

He didn't expect anything in return but would take whatever they

gave him.

Feyzi Kishi knew that Salman had fought in Karabakh; maybe that's

why he used to hang around the store so much. Once he even tried

to get Salman to talk. He asked him in which part of Karabakh

he had fought. Salman quickly muttered that he had not fought

in his region at all. They never brought up the subject again.

Once I saw Feyzi Kishi laugh. He had learned that I was studying

at the institute and had asked me what I was going to become

after graduating. Salman answered for me. "After he graduates,

he'll become a scoundrel," he said.

Feyzi Kishi gave a chuckle when he heard this. He laughed: "Don't

talk like that. He looks like an intelligent boy." It was

the first time that I was not offended by Salman, because his

words made Feyzi Kishi laugh.

During my winter exams, I came to his store nearly every day

in order to gain Salman's favor. I held my books under my arms

and in order not to return home in the afternoon, brought my

own food. I used to have lunch at the store so that Salman could

leave the store when he needed to.

One day, Feyzi Kishi was sitting quietly near the heater. I was

reading my textbooks and not paying attention to him. When Feyzi

Kishi stood up to leave, Salman took a plastic bag and filled

it with various things so that he wouldn't leave empty-handed.

But Feyzi Kishi's hand remained outstretched. He asked for money.

Salman faltered and asked, "Why do you want money?"

Feyzi Kishi replied, "I need it."

"Why do you need it?"

"I just need it."

Salman turned and looked at me. He had a strange expression on

his face. It was as if Feyzi Kishi had just insulted him. "Why

do you need money?"

This time Feyzi Kishi didn't say anything more. He just shrunk

low where he was standing.

Salman couldn't hold still and bustled about. Then he stood in

front of Feyzi Kishi. He was still holding the bag.

"Why are you still alive?" he whispered.

I was afraid that Feyzi Kishi would start to cry any minute.

I muttered something to try to calm Salman down. But he didn't

hear me.

"What's the meaning of living any more? Are you going to

find a son again? Get married? Settle down? Why don't you just

die, man!"

Feyzi Kishi didn't raise his head. He left the store very slowly.

I couldn't maintain my composure. "You had no right to do

that. He's an old man"

Salman yelled at me: "Shut up! Everyone tries to act as

if they were nice people. If you don't like it, f- off from here."

I stood up, took my books and left. Two or three days later,

I went back as if nothing had happened.

One evening, the District Inspector appeared at the door. Immediately,

Salman started digging in his pocket for money [for a bribe].

But actually the District Inspector had come for something else.

He showed us Feyzi Kishi's photo. We learned that they had discovered

his dead body in the bazaar that morning and were trying to find

out where he lived. When the Inspector wasn't able to find out

any information from us and started to leave, he saw the money

that Salman was holding in his hand.

"I see you want to give me some money," he said. "Don't

be shy. Just give it to me."

Salman looked at me. "What are you going to be when you

graduate?"

"I'm going to become a scoundrel," I said.

Salman smiled. "Good for you. This time, you get the money."

I stretched out my hand to take it.

Footnote:

1 Kishi

is an expression of polite address or reference, meaning "man".

It follows a man's first name, in this case, meaning Mr. Feyzi.

Translated

by Vafa Mastanova

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.1) Spring 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.1 (Spring 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|