|

Spring

1999 (7.1)

Pages

20-21

Oil Boom Period

in Azerbaijan

Husein

Javid

(1882-1944)

Husein Javid was one

of Azerbaijan's most gifted and esteemed writers of the 1920s

and 1930s. He is remembered for his poetic tragedies, especially

"Sheikh Sanan," a historical drama about an Azerbaijani

who falls in love with a Georgian girl named Khumar. At the time,

the idea of a high-ranking Muslim clergyman falling in love with

a Christian woman, carrying a cross and becoming a swineherd

was scandalous. Eventually, however, love and humanity triumph

over religious bigotry. Husein Javid was one

of Azerbaijan's most gifted and esteemed writers of the 1920s

and 1930s. He is remembered for his poetic tragedies, especially

"Sheikh Sanan," a historical drama about an Azerbaijani

who falls in love with a Georgian girl named Khumar. At the time,

the idea of a high-ranking Muslim clergyman falling in love with

a Christian woman, carrying a cross and becoming a swineherd

was scandalous. Eventually, however, love and humanity triumph

over religious bigotry.

In 1937, Javid was arrested by Stalin's regime on charges of

being a founding member of a counter-revolutionary group that

was organizing a coup. The accusations were false but impossible

to disprove, and he was sentenced to eight years of imprisonment.

He died in exile in Siberia in 1944, one year short of completing

his sentence. His reputation was not cleared until much later

after the death of Stalin (1953).

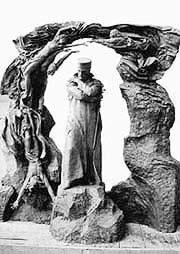

In June 1993, a statue to Javid's memory was erected on the grounds

of the Academy of Science in Baku. The immense sculpture was

designed by Omar

Eldarov

(now

a member of Parliament). In October 1996, Javid's

mausoleum

was

dedicated in the land of his birth, Nakhchivan - the non-contiguous

part of Azerbaijan separated from the country's mainland by a

small strip of territory, which the Bolsheviks gave to Armenia

in the early 1920s.

[See: AI 4.1, Spring 1996, "The Night Father

Was Arrested"

by Javid's daughter and sole survivor, Turan Javid, page 24.

Also "Aliyev

Memorializes Literary Giant" in AI 4.4, Winter 1996, page

37.]

Portrait: by Gunduz.

Photo: Statue to the memory

of Husein Javid at the Academy of Science campus in Baku. Sculptor:

Omar Eldarov. Photo: Statue to the memory

of Husein Javid at the Academy of Science campus in Baku. Sculptor:

Omar Eldarov.

Oil: the

Pros and Cons

Conversation Between Masud & Shafiga

Written before the Bolshevik Revolution (1912)

Even today Azerbaijanis

are quick to admit that oil is both curse and blessing to their

nation. Here, in a rather straightforward, didactic piece, Javid

points out the irony that a natural resource could bring so many

advanced conveniences to contemporary life but be so slavishly

hellish to produce. Many of the poet's arguments still stand

today despite the fact that he believed the future would reveal

solutions to these problems. Here, discussion centers upon the

harmful environmental effects and the abuse of human rights in

producing the oil.

The poem begins

with a discussion between a young couple, Masud and Shafiga,

who are looking for a park in which to take a romantic stroll.

Shafiga draws her friend's attention to the oil fields in the

distance and satirically points out that, indeed, there is a

forest in Baku - a forest of oil derricks.

People are always looking for

happiness in daydreams.

But Truth is more tears than smiles,

strange as it seems.

-Husein

Javid (Pre-Soviet)

Left:

Forest of oil wells outside Baku, early 20th century.

Courtesy Azerbaijan National Archives.

Shafiga:

Look!

As far as eye can see-a forest of enchantment!

Like a panorama viewed from a magic casement!

Do you see what I see? All that you said is untrue...

You told me-remember? If one searched the whole town through

One could not find a single park; there would not be one in sight.

But aren't those trees, after all, now dry,

Don't they prove you weren't right!

How's this for a view? How marvelous it seems!

You look, and the joy of Spring enters your heart. It's a dream.

Who could help being happy, walking through such a wood?

Why, good gracious, Masud! Doesn't it do your heart good?

(Her face darkens)

What a sarcastic laugh...such a frustrated expression!

What's on your mind, then? Talk, don't keep me waiting.

Masud:

Well,

what can I say? It's a very pretty picture you drew-

Everything's beautiful...love on earth: but too good to be true...

Not an everyday sight. The place makes a marvelous impact.

But your fantasy is a dream. It doesn't correspond with the facts.

People are always looking for happiness in daydreams.

But Truth is more tears than smiles, strange as it seems.

Take that cypress there, for example, it certainly draws the

eye:

But better take a good look at those towers like cypresses high.

They're not green, are they? But black as the soot from a stove.

A forest of dirty oil-derricks-grove after grove.

They are dark ranks of tombstones, alive with awful sound:

And what a foul, repulsive smell they spread here, all around.

This is no forest cool, with flowers and grass-all is bare and

harsh.

If you go closer, you will see there's only an evil marsh.

You won't even find water that's fit to drink. It's pure hell.

Black, ugly pools all over from these ever-spouting wells.

And what you call a forest...stinks to high heaven! Nothing grows.

It kills a man, chokes him to death: and no one cares or knows.

Those working here lose all their strength and forfeit all their

health:

And from the workers' sweat and toil-why, others grow in wealth,

And fatten on the poor fools' patience, utter lack of rights.

On the workers' faces you can read their fate, their plight.

Among the bored-wells, blackened with smoke....

That's a lovely view!

Yet they keep hoping sometime things will change, a new

Life will dawn, and fortune's smile will beam at long last.

Oh, what dreams they have! What sorry, ridiculous dreams!

And what they don't endure for all those dreams. If you but knew

just what their life is like. I wish you'd look, and look anew!

What you would see you could not bear, from tears your eyes would

grow red-

And that is how these human souls must earn their daily bread.

Shafiga:

No, oh no! I don't want to look. Come, let's go away.

Masud:

But why? Won't you tell me why, my darling? Why not stay?

Shafiga:

Need you ask why? Bend down and listen how my heart races:

You'll know then how I feel. I did not know all this deceit.

Look at me! Now I see here only cruel catacombs.

How can I bear to look, unmoved? While it's still light, let's

go home.

Now I shall think only of the needy, the strangers and the sick-

Who come to work here for a crust of bread...and are foully tricked.

Why, our parts give only bitter fruit to these unfortunates.

I'm sorry for them. Such cruel labor brings no benefits.

If you think of their immense labor, the pay is very slight:

On their bent backs the sun burns down in spite.

They are black with oil. They keep on coming...here awaits

Them only a hard life. Even death may be their fate.

They all have mothers, wives, and children, a home-

Who wait for their return, with eyes turned ever on the road.

Sad and lonely, hungry families in some far off land

Expect them back...today, tomorrow...just as planned

In vain. The workers' eyes will close upon the world. They won't

survive.

And could you call this life, even if some do stay alive?

They live as if in mourning-live on hope, on hope alone.

They all have sunken chests; half-naked, skin and bone.

So they live today; and so tomorrow, if, at all-

Backs bent, up to their knees in mud, until their final fall.

The slimy holes and oil-filled pools will form their graves:

Fate itself prepared such bogs for all these sorry slaves.

Such is life, hard life; and, somehow, people drag it out.

I wonder how many souls have died on these derrick torture-racks?

Some with smashed ribs, or hands, or broken backs...

No matter where they come from, here they are all equal:

One end is sure-a bitter cruel death will be the sequel.

No, no, I won't go closer. My pity knows no bounds-

I feel that trouble haunts each derrick, waits all round.

The workers have tormented faces: there's no joy here, or peace...

Only a torrent of black oil, and faces dark with grease.

Yes, these are ranks of tombstones, not cypress trees:

A forest, but a dead one, no grass, no green-I weep

That some, such torment sow; and others, suffering reap.

Masud:

Upon this question, angel mine, you've made a slight mistake.

You have the right idea, love, but I wouldn't have you make

It out that all the world is pain and grief; with no delight.

Homes now have light and warmth; and all our world's more bright.

The black oil gushing from these wells is a mighty force:

For people's happiness, it has become a living source.

This is gold, real treasure, flowing from these fields.

Just think what these wells mean, and what they yield:

They are man's new idol, and the road to riches pave-

The country without them practically faces the grave.

The cities grow in splendor, and in social eminence-

A broader, happier life will come from this magnificence.

The fine statues, the beauty, improvements that come on the scene,

In town all you've felt or heard about or ever seen

Is the proud product of these wells-so evil-looking here...

Now do you understand? You know what it means, my dear?

Shafiga:

Better than you, perhaps. It is clear, some will have splendor,

Live the rich life of the well-to-do big spender-

And never know grief or sorrow, or deepest poverty.

Well, let them have it, their full life. But here is misery.

All these needy creatures slaving among the oil wells-

Let them swallow and choke on this gas straight out of hell?

Let them fade from day to day until at last they die?

The question is: Why? Why must they live like pigs in a sty,

In damp sod dug-outs, through the hottest sun or pouring rain?

Then where is justice, and where is truth? You think it is humane?

Masud:

It's a complex question, and one most difficult to solve;

I haven't the strength to do it. Yet we should involve

Ourselves. To find the answers in our day

Is quite beyond us. But these questions will not stay

Unanswered, as sure as there's a sun in the sky-

To all the questions in our hearts, the Future alone can reply.

Translated by Gladys Evans for "Azerbaijanian Poetry-Classic,

Modern and Traditional," edited by Mirza Ibrahimov. Progress

Publishers: Moscow. No date (probably late 1970s).

From Azerbaijan

International

(7.1) Spring 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.1 (Spring 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|