|

Summer

1999 (7.2)

Page

11

Editorial: Colors

of the Century

An Artistic

Perspective

by

Betty Blair

As many of you know,

the drive between Baku's airport and the city itself can be rather

disconcerting. For miles, you pass nothing but desolate landscapes

with soil so saturated with oil that nothing grows. Rusty "nodding

donkeys", like mindless robots, stand isolated and neglected,

forever pumping that black sticky oil from the belly of the earth.

More than once I've asked myself, "What am I doing in this

God-forsaken place? Is this the "real Azerbaijan"? As many of you know,

the drive between Baku's airport and the city itself can be rather

disconcerting. For miles, you pass nothing but desolate landscapes

with soil so saturated with oil that nothing grows. Rusty "nodding

donkeys", like mindless robots, stand isolated and neglected,

forever pumping that black sticky oil from the belly of the earth.

More than once I've asked myself, "What am I doing in this

God-forsaken place? Is this the "real Azerbaijan"?

This past year, a considerable number of foreign journalists

from major media have traveled this same route on assignment

to this "exotic", little-known, often mispronounced,

dot on the world's map. They "parachute" in to Baku

for a few days, hang out at the foreign pubs, and spend most

of their time with others who speak their same language. In the

blink of an eye, they're heading back home, story in hand, assignment

complete, eager to move on to the next reality. In the name of

"objective reporting", their analyses usually turn

out to be as superficial as the thin film of dirt that settles

everywhere over the city everyday.

Such an approach to news could be viewed as the flip side of

the same coin that Soviet officials imposed on Art policy for

most of this century. Both deal primarily with the illusion of

physical appearances.

While international

journalists tend to paint a picture of desolation, misery and

depression with little hope of recovery except through the great

panacea of oil, Social Realism mandated that artists paint life

full of eternal optimism, images of courage, confidence and determination.

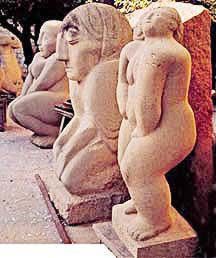

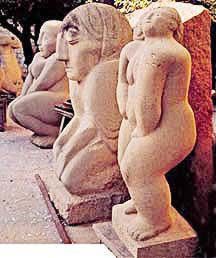

Photo: Works by Azerbaijani

sculptor Fazil Najafov.

Azerbaijani sculptor

Fazil Najafov (page 60) was not the only art student denied a

university degree from Moscow for challenging this vision of

the socialist system. His final project in 1961 depicted exhausted

oil laborers leaning up against a pipeline. But Soviet workers

weren't supposed to look fatigued. Labor was to be glorified

and work romanticized, and Fazil returned to Baku empty-handed

without a diploma. Azerbaijani sculptor

Fazil Najafov (page 60) was not the only art student denied a

university degree from Moscow for challenging this vision of

the socialist system. His final project in 1961 depicted exhausted

oil laborers leaning up against a pipeline. But Soviet workers

weren't supposed to look fatigued. Labor was to be glorified

and work romanticized, and Fazil returned to Baku empty-handed

without a diploma.

Of course, as in every population on earth, there were, still

are, and always will be, those who succumb to the gods of ideology,

whether it be despotism, tyranny, commercialism or whatever.

After all, artists need to eat just like the rest of us. That's

why countless paintings were dedicated to the glories of the

proletariat in the Soviet republics. In Azerbaijan, they took

the shape of sinewy, tough oil workers and sun-toughened collective

farmers.

In this issue "Colors of the Century - An Artistic Perspective",

we've left out most samples of Social Realism with the one exception

of Tahir Salahov, an immensely gifted artist, who found ways

to paint in a realistic style without always making everything

"rosy".

Here we've focused primarily on major personalities who have

given modern art its distinctive Azerbaijani signature. Unlike

writers who were killed for their quest for freedom, dissident

artists were simply ostracized and their works simply not included

in exhibitions [See Century of Reversals, AI 7.1]. And so artists

of conscience suffered from not being assigned projects - no

work, no bread - and were left at the mercy of the good will

of othersalong with cheap cigarettes and too much alcohol. It's

our great loss that most of these extraordinary artists did not

live to celebrate their 70th birthday.

Starting in the late 1950s and 60s, what is now referred to as

the "Absheron School" formed the ideological basis

for Azerbaijan's modern art movement. East from Baku on the peninsula

that comprises the "eagle's head" of Azerbaijan's map,

there is a small village called Busovna where this movement got

started in a run-down dilapidated cottage. Javad Mirjavad was

its driving force.

The movement was given birth while he was studying in Leningrad.

Javid had learned that numerous paintings from European Impressionists

and Post-impressionists, along with the African and Mexican works,

were not exhibited at the Hermitage Art Museum but kept in their

storehouses while the KGB "kept tabs" on anyone showing

too much interest in such approaches to art.

One day Javid decided to approach the Director of the Hermitage

determined to get a look for himself. As the story goes, he first

went out and "got himself tipsy" and then half jokingly,

half seriously, threatened the Director: "Either you give

me permission to go into the storerooms or I'll kill you."

The Director understood Javid's passion and replied, "What's

the use of killing me, just go and sit there as long as you wish."

And so for several months, Javid explored the storehouse, marveling

at the works that were denied the public.

Transformed by what he saw, Javad set fire to all of his own

works, destroying everything (see page 31). Then, he returned

to Azerbaijan to start anew. Gorkhmaz Afandi, Kamal Ahmad, Rasim

Babayev, Hamza Abdullayev, Fazil Najafov and Farhad Khalilov

were among those who followed him over the course of several

years.

The Absheron School has its own distinct characteristics. Works

are passionate, provocative, often enigmatic, and always highly

political. They are deeply infused with strong colors emblazoned

by the harsh rays of the Absheron sun. Forms are exaggerated

and works aren't necessarily "pretty"; they bite and

kick and scream in their attempts to counter the Establishment.

This is the legacy that young artists who paint and sculpt in

Azerbaijan today have been influenced by.

In our modern world of satellite communication in which we have

instant access to view events happening even in remote places

on the other side of the earth, one might ask whether we need

artists anymore. In past centuries, much artwork was descriptive

of customs and traditions. But now with such a proliferation

of recording equipment, both oral and visual-tape recorders,

cameras, videos, scanners and the Internet - who needs artists

anymore?

The genuine Artist would reply, "You need me because I show

you things invisible to the naked eye - both beautiful and hideous.

I bring perspective, social and psychological context and interpretation.

I dream of how things could be and at the same time I writhe

in pain at the wrongs and evils of our day." And it is exactly

for this reason that we need artists just as much as they need

us.

It's no secret that Azerbaijanis artists are struggling these

days just as everyone else in the Soviet Republics who are trying

to make the transition into the world market economy. It's for

this reason that we've included the artists' contact numbers

here, hoping that some art lovers will initiate relationships

and friendships. If you don't know Azeri or Russian, find a friend

to make the initial contacts for you. You'll be deeply enriched.

In the meantime, we'd like to challenge journalists and visitors

alike who suddenly find themselves landing at Baku's Airport

to check out the country's "invisible" landscapes -

as envisioned by its painters and sculptors, its writers, dramatists

and musicians. If you're really determined to understand this

country, don't take all your clues from the desolate landscape

that lines the route between the airport and your five-star hotel.

From Azerbaijan

International

(7.2) Summer1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.2 (Summer 1999)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|