|

Summer

1999 (7.2)

Pages

60-64

Fazil Najafov

(1935-

)

The Expressive

Magnificence of Stone

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Fazil Najafov Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Fazil Najafov

The haunting images

found in Fazil Najafov's Sculpture Garden invite you to speculate

on their ambiguous meanings. For example, his bronze sculpture

"Three Blind Men" (1979) shows three men clutching

onto each other, struggling to remain standing. Two of them stare

blankly up into the sky, oblivious to the sun above them.

The emphasis here is not on realistic detail-their clothing,

hair or anatomical correctness-is unimportant. Instead, Fazil

seems to be revealing something more symbolic. Perhaps, it was

the crippling blindness of living under a repressive Soviet government

(that would collapse 12 years later) or could it imply the blind

aspiration of our generation busily scurrying about not knowing

the direction of their own destination?

Fazil says that he based the sculpture on childhood memories

of blind men who used to wander along the streets praying. He

refers to this sculpture as one of his more "pessimistic

and sensitive" works.

In April 1999, we asked Fazil about what it was like struggling

to maintain his artistic vision, especially when confronted by

a Soviet government that strongly disapproved of such ominous

abstract images.

Fazil Najafov was an extraordinary

student at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow. For his final

art project in 1961, he decided to create a work specific to

Azerbaijan, something that reflected the life of the oil workers

in his country. His clay sculpture depicted an exhausted oil

worker leaning his tired body against a steel pipeline. The inspiration

for the sculpture had come from Fazil's visit to Oil Rocks, where

he witnessed the difficult conditions under which the oil workers

lived and worked. At that time, this small town built up over

the Caspian on wooden piers was hardly ten years old. Oil Rocks

was the first experiment by the oil industry for drilling offshore

for oil, not only in Azerbaijan but in the entire world. Fazil Najafov was an extraordinary

student at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow. For his final

art project in 1961, he decided to create a work specific to

Azerbaijan, something that reflected the life of the oil workers

in his country. His clay sculpture depicted an exhausted oil

worker leaning his tired body against a steel pipeline. The inspiration

for the sculpture had come from Fazil's visit to Oil Rocks, where

he witnessed the difficult conditions under which the oil workers

lived and worked. At that time, this small town built up over

the Caspian on wooden piers was hardly ten years old. Oil Rocks

was the first experiment by the oil industry for drilling offshore

for oil, not only in Azerbaijan but in the entire world.

When Fazil turned in his project, the authorities deemed it unacceptable

and "unprofessional". What they meant was that it was

too controversial-Soviet workers weren't supposed to look fatigued.

Labor was to be glorified, workers to be romanticized. The authorities

thought that Fazil's tired workers looked more like convicts

than contented workers.

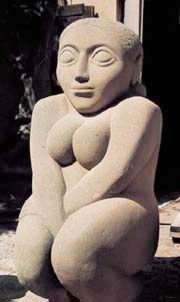

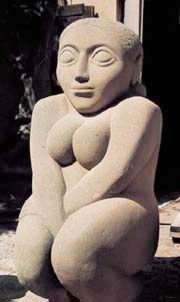

Fazil Najafov, "Morning", 2 x 1 x 1 m, stone, 1983.

He was ordered to destroy the sculpture and submit a different

work. He refused. They threatened him by saying that he wouldn't

receive his university degree, but Fazil wouldn't budge. They

gave him another chance to submit a different project, this time

suggesting that he create a small statue of a Pioneer (youth

group of the Communist party). They even offered him 2,500 rubles

for it. Fazil still turned them down and returned to Baku without

his degree.

The Purpose of

Art

This kind of treatment was typical for artists during Soviet

rule. Art was to be created for propagandizing the government's

goals. Many of Fazil's professors who disagreed with this concept

were fired. Fazil himself disagreed with the government's restrictions.

He recalls, "When we read in books and heard from others

about art from democratic republics, we saw that the purpose

of art was far different from what we had been taught."

Fazil Najafov, "Echo

of an Epoch," 85 x 65 x 45 cm, bronz, 1979. Fazil Najafov, "Echo

of an Epoch," 85 x 65 x 45 cm, bronz, 1979.

Fazil

came up against similar objections when he submitted a work for

an exhibition commemorating World War II which was held in Moscow

in 1965. Again, his work was rejected for being too "pessimistic".

Even though it had been praised in Azerbaijan, the Russian generals

on the committee of the Moscow exhibition objected, saying that

it would be a shame to exhibit such a work, since the Soviet

Union had been victorious in the war.

At that time, Soviet art was supposed to reflect only one kind

of "ism"-Social Realism. All other "isms"-Impressionism,

Expressionism, Surrealism and Modernism-were held under suspicion

and considered dangerous-like a ticking bomb ready to go off

at any time.

Artists who were willing to promote Communist ideology were courted

by the Soviet regime. Those who chose to erect monuments to past

and present Soviet leaders received awards and privileges, were

offered studios and honorariums and were assigned government

contracts. Accordingly, most artists chose to submit to the government's

mandates.

Exhibitions were planned around political themes, such as "We

Are Building Socialism," "Labor and Human Beings,"

"Lenin's Anniversary"-commemorating his 70th Jubilee

(date of birth), then his 80th, 90th and 100th. No artist could

stray far from the given theme and still expect to place his

work in the exhibition.

"Real"

Artists

In Azerbaijan, however,

the pressure on artists to conform was not as severe as it was

in Moscow. Since the professional level was lower, according

to Fazil, and there were fewer artists, it was easier for him

to make a name for himself as an artist despite not having the

government's blessing. Fazil says that the Soviet regime influenced

the great majority of Azerbaijani artists; only a few managed

to create what he would identify as "real art". In Azerbaijan, however,

the pressure on artists to conform was not as severe as it was

in Moscow. Since the professional level was lower, according

to Fazil, and there were fewer artists, it was easier for him

to make a name for himself as an artist despite not having the

government's blessing. Fazil says that the Soviet regime influenced

the great majority of Azerbaijani artists; only a few managed

to create what he would identify as "real art".

This alternate group of artists included such outstanding artists

as Fuad Abdurrahmanov, Javad Mirjavad and his brother Tofig Javadov

along with their cousin Rasim Babayev. Artists from the following

generation included Kamal Ahmad, Husein Hagverdiyev and Ujal

Hagverdiyev. As a rule, these artists were less respected and

less popular and often passed over, instead of recognized. Many

of these "underground" artists were not granted university

diplomas, another deterrent that held them back professionally.

Without his diploma but still determined to be an artist, Fazil

returned to Baku after his confrontation at the Art Institute.

He took part in various exhibitions and joined the USSR Artists'

Union. In 1969, he was allocated the studio space where he still

works today.

Recalling what it was like to make a name for himself in Baku,

Fazil says, "Though I was young, I was esteemed among the

professional artists. No matter what exhibition I offered my

works, they accepted them. Sometimes my works were even sent

to Moscow, which was considered very prestigious at the time."

Fazil Najafov, "Commemoration of Victims of World War

II, 25 years later," 3 x 1 x 1 m, 1965.

Abstract Motifs

One

of Fazil's first official assignments in Baku, a commission by

architect Yusif Gadimov, was the copperwork on the outside walls

of the House of Actors (1970). "The concept of this work

is intellectual since the House of Actors is an institution of

intellectual and thinking people," says Fazil. "There

were different motifs and forms in the work. I tried to express

something with movement and pantomime. I wanted to symbolize

these things." One

of Fazil's first official assignments in Baku, a commission by

architect Yusif Gadimov, was the copperwork on the outside walls

of the House of Actors (1970). "The concept of this work

is intellectual since the House of Actors is an institution of

intellectual and thinking people," says Fazil. "There

were different motifs and forms in the work. I tried to express

something with movement and pantomime. I wanted to symbolize

these things."

Apparently, Baku's art officials didn't understand Fazil's symbolism.

After the sculpture was erected, he was attacked for being "formalistic".

The sculpture was promptly removed and Fazil had to write an

"explanation" of what he had done. He was essentially

blacklisted and accused in speeches by high-ranking officials.

Fazil spent many of the following years in disgrace; even his

close friends avoided him. Later, at the Tbilisi Biennial Art

Exhibition in 1986, he was awarded the Grand Prize for being

the "Most Disgraced of the Most Talented Artists."

Fazil Najafov, "Stories of Life", bronze, 1987.

Happiness is exposed to the public; misery is hidden.

Fazil got into trouble because Soviet art was supposed to use

realistic forms, not symbolic ones. Artists who added abstract

notions to their works ran the risk of being considered "anti-Soviet".

For instance, one of Fazil's bronzes entitled "Stories of

Life" (1987) holds controversial layers of meaning that

may not be so obvious at first glance. The sculpture depicts

two themes: on the top level, he depicts family members all smiling,

content and lovingly embracing each other. The lower part of

the sculpture reveals hidden, grotesque faces and relationships

that are never exposed to the world. The work depicts a family,

but could it not also represent larger institutions and nations?

Soviet Legacy

The constraints imposed by the Soviet government on artists have

been far-reaching. It's true that during the Soviet period, many

individuals did get the chance to study and pursue careers in

art. Today there are more than 800 sculptors and painters in

Baku but few among them, according to Fazil, are "real"

artists. "Without contracts from the government, most Azerbaijani

artists have no means of support. In the past they were used

to fulfilling the orders that they were assigned, but many of

them don't know how to do anything besides that. The human initiative

and creativity that Soviet system snuffed out has been slow to

reemerge," Fazil observes.

"For artists in Azerbaijan today, it's as if an army general

commanded his soldiers to take off their heavy shoulder straps

and cumbersome waist belts and begin to move about freely. It's

as if he told them: 'Go and do what you are able to do,'"

says Fazil. "If you're an artist capable of doing something,

if you're someone who really comprehends what art is all about,

you'll be able to achieve something. Those who can't are in an

awkward situation. Unfortunately, in the meantime, many artists

have succumbed to the whims of commercialization to satisfy the

wishes of potential customers-not all artists, of course. There

are still those who create real art."

Despite these current economic difficulties, Fazil says that

he prefers the current situation. He has managed to sell some

of his works to foreigners, but admits that he doesn't earn any

more money today than he did prior to independence. "The

difference is that now we have the freedom to work and create

as we want to. Now we can express our thoughts freely."

With an eye to the future, Fazil concentrates on his favorite

medium-stone. "I have always been sensitive to stone. It

seems that I understand the nature of stone and, in turn, it

understands me, too. Stone retains the memory of millions of

years, guarding the secrets of time deep inside it. With stone

you can create something monumental, something eternal; you're

not dealing with cardboard. In a single word, I love stone. I

like bronze, too, but nothing attracts me as much as the expressive

monumental silence of stone."

For more

photos of Fazil's sculptures, see "Fazil Najafov: Frozen

Images of Transition" [AI 3.1, Spring 1995]. His studio

is located at Ashug Juma Street, 851/52. Home Tel: (99-412) 61-53-49;

Studio: 66-71-09; Fax: 93-12-76.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.2) Summer1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.2 (Summer 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of  Fazil Najafov was an extraordinary

student at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow. For his final

art project in 1961, he decided to create a work specific to

Azerbaijan, something that reflected the life of the oil workers

in his country. His clay sculpture depicted an exhausted oil

worker leaning his tired body against a steel pipeline. The inspiration

for the sculpture had come from Fazil's visit to Oil Rocks, where

he witnessed the difficult conditions under which the oil workers

lived and worked. At that time, this small town built up over

the Caspian on wooden piers was hardly ten years old. Oil Rocks

was the first experiment by the oil industry for drilling offshore

for oil, not only in Azerbaijan but in the entire world.

Fazil Najafov was an extraordinary

student at the Surikov Art Institute in Moscow. For his final

art project in 1961, he decided to create a work specific to

Azerbaijan, something that reflected the life of the oil workers

in his country. His clay sculpture depicted an exhausted oil

worker leaning his tired body against a steel pipeline. The inspiration

for the sculpture had come from Fazil's visit to Oil Rocks, where

he witnessed the difficult conditions under which the oil workers

lived and worked. At that time, this small town built up over

the Caspian on wooden piers was hardly ten years old. Oil Rocks

was the first experiment by the oil industry for drilling offshore

for oil, not only in Azerbaijan but in the entire world.

One

of Fazil's first official assignments in Baku, a commission by

architect Yusif Gadimov, was the copperwork on the outside walls

of the House of Actors (1970). "The concept of this work

is intellectual since the House of Actors is an institution of

intellectual and thinking people," says Fazil. "There

were different motifs and forms in the work. I tried to express

something with movement and pantomime. I wanted to symbolize

these things."

One

of Fazil's first official assignments in Baku, a commission by

architect Yusif Gadimov, was the copperwork on the outside walls

of the House of Actors (1970). "The concept of this work

is intellectual since the House of Actors is an institution of

intellectual and thinking people," says Fazil. "There

were different motifs and forms in the work. I tried to express

something with movement and pantomime. I wanted to symbolize

these things."