|

Summer

1999 (7.2)

Pages

31-38

Javad Mirjavad

(1923-1992)

Emblazoned

by the Sun

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Javad Mirjavad Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Javad Mirjavad

Javad Mirjavad

rarely put his thoughts and feelings on paper with words. Usually,

they were emblazoned across canvases in passionate hues drawn

from the sun. Today, his paintings brighten museum walls in Baku,

Moscow, Paris, Rome and London, as well as the private homes

of such celebrated thinkers as Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Arthur

Miller and Chingiz Aytmatov (Kirghiz writer).

The following excerpts from his diary show how Javad's work evolved,

becoming increasingly influenced by African and Latin American

art. With vibrant colors and outbursts of emotion, his paintings

tantalize the senses, much like the foreign sculptures and paintings

he admired from afar.

Excerpts from his

diary

Heart

Attack. January [1983]. It seems to me that all the winds blowing

in the Absheron Peninsula Footnote 1 sift through the cracks in the walls and windows

in this hospital ward. Even the feelers on one of the cockroaches

are quivering as it meanders across the wall. At night the cold

wind howls like a ghost outside my window. It was on such a night

accompanied by such mournful wails that my birthday arrived:

sixty.

My eyes won't close

in sleep. Thousands of thoughts race through my mind. I have

no visitors. The whole world seems to have forgotten me. No one

needs me. Only my wife-the most pitiful and miserable creature

in the world-is standing watch day and night, guarding me from

the clutch of death. My eyes won't close

in sleep. Thousands of thoughts race through my mind. I have

no visitors. The whole world seems to have forgotten me. No one

needs me. Only my wife-the most pitiful and miserable creature

in the world-is standing watch day and night, guarding me from

the clutch of death.

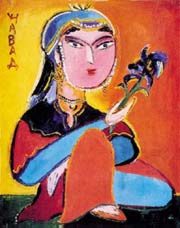

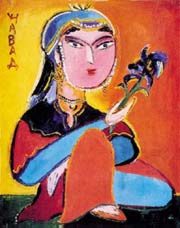

Above: Javad Mirjavad, "A

Girl With an Iris", from the series, "Improvisations

based on themes from Eastern Miniatures," 1986.

One day the Devil turned up on the ward. The first words he uttered

as he crossed the threshold were: "God bless you! You don't

look at all like a dying man." But I have died a thousand

deaths in my paintings-to die one more time seems so easy.

Here I am, lying in the filth of this ward. I am not complaining

and criticizing anyone-I've been a happy man. Dying was sure

to happen sooner or later. That's destiny.

The most important thing is that I've never betrayed my conscience.

And I never will. I've lived just as I have wanted to. I have

spent most of my life in nature, enjoying and loving everything

created by God. I've drawn my colors from the sun and copied

these blazing colors on my canvases. I've merged the spirit of

my heart and soul with these colors and produced a considerable

number of paintings. That same spirit continues to win the hearts

of viewers even now. . .

But no one seems eager to understand my works. The most troubling

thing is that they don't want to. People are sick. They want

to be spoon-fed. They need "art porridge" so that they

can swallow it easily, without effort. People do not understand

one another, so how is it possible for them to fathom the world?

. . .

The Devil said: "Do you believe all that nonsense? It's

all a fairy-tale, a legend-and an old and hackneyed one at that."

And I replied: "No, it's not a legend. It's truth. What

about Giordano Bruno [1548-1600] and Van Gogh [1853-1890] and

Arto, who are even closer to us? [Walt] Whitman [1819-1892] once

wrote: "Oh, cruel sun! If another sun like you didn't rise

inside me every day, you would have destroyed me!"

|

|

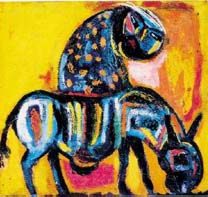

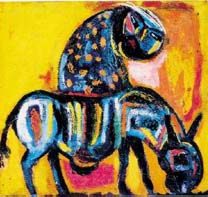

Left: Javad Mirjavad, "Watering

Place," 1986.

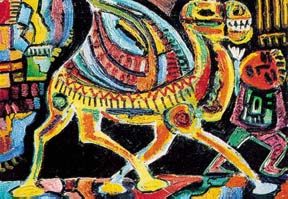

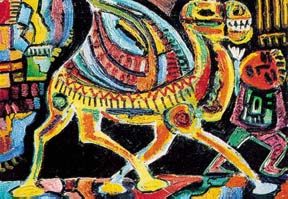

Right: Javad Mirjavad, "Caravan

Driver", from the series, "Improvisations Based on

Themes From Eastern Miniatures,"1986.

Leonardo

da Vinci [1452-1519] once observed: "Millennia will pass.

Nothing will be left of us in this world except the legends that

they have made up about us!" May the legends of Prometheus

live long, but not those of Faust who sold his soul to the devil.

I feel very weak and exhausted after the heart attack. I can't

do a single thing by myself. I won't be able to return to my

former self. The premonition of death chases me. I fear lest

I should not have enough time to realize all the dreams that

I've been cherishing in my heart. It seems to me that I've been

searching for such ideas all my life. Now, finally, I realize

that I can finally paint them with all their nakedness and tenderness.

Now, even a minute wasted away without being devoted to art is

an ordeal for me. Bit by bit, gradually, I'll give up all my

doubts and my spirit will cool down-my spirit which has always

been as fiercely hot and turbulent as a volcano.

I must have been living with all these emotions inside me since

childhood when I used to walk barefoot in my grandfather's garden

in Fatmayi-a village near Baku. It was then that those senses

crept into my blood from the scorching earth of the sun's hot

summer rays and awakened my spirit. These senses grew together

with me and matured. I have carried them from my youth up until

today. Nothing can stifle these emotions inside me. That's what

has given me strength, bursting forth from my brain. Ever since

I realized that painting was my destiny, I have been working

day and night like a madman.

And now look at me-my feet are hardly able to hold me up. I pray

to God, beseeching Him to give me time to accomplish my final

works.

Life and Death

Is there another life beyond this one? Is there another world,

ruled by wisdom or manifested in some other shape? Do other worlds

exist? Everything is relative in life-the world that we can see

and the world that we cannot see. Maybe we return to this world

after our death. In fact, when it seems that we are acting against

our will, it is our memories that are ruling and directing us.

Our ancestors used to explain it perfectly.

I used to "see" one and the same dream repeatedly for

a long time:

there were mountain ranges running amidst the sea along the coast

where I grew up. But nowadays not even a small island exists

there. Recently I read in a scientific source that in the olden

days, this region was a junction for the two shores of the Caspian

Sea. Maybe I've seen it myself-not now, but in a previous life.

Maybe my ancestors had seen it and transmitted it to me through

their memories.

When I first saw one of my brother's paintings [Tofig Javadov],

I became overtaken by despair; it frightened me so-like a premonition

that some disaster was awaiting our family in the near future.

It was later that I named that canvas "A Note of Mourning".

Less than ten days passed before Tofig met his tragic death in

Moscow.2

The world is full of mysteries. And we, like those stone statues

on Easter Island, with eyes fixed eternally on the sky, search

for the key to all those mysteries in the profundity of our own

selves and in the depths of the universe.

We have become completely estranged from nature. We have forgotten

the language with which to communicate with it. We are all fumbling

about blindly. We seem to be constantly on the run in a senseless

way. All this is portrayed by Bosch [Hieronymus, 1450-1516] perfectly

on canvas and also in the book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible.

I remember once I couldn't sleep a wink the entire night, tossing

from side to side in my bed until morning. It was as if some

premonition had seized me. My heart was throbbing with an uneasy

anxiety as though it were whispering "Death, death!"

Not only my heart but everything around me was chanting that

one solemn word. It turned out that on that very night, my brother

lay drowning in his own blood a thousand kilometers away.

The rituals of Siberian shamans tell us more about life and death

than these primitive "realistic" paintings in our exhibitions.

Grasping the meaning and the subject matter of a painting, an

icon, a miniature or an Eastern pattern heightens one's imagination.

It intensifies one's insight of supernatural phenomena. The content

of certain architectural and sculptural monuments, the characteristics

of some metals belonging to the Asian continent, the method of

mummification-all this still remains a mystery.

Long, long ago, our ancestors passing through the Alaska Peninsula

laid the foundation of a great culture overseas. An Asiatic was

searching for the essence of life and he found it. And he could

encapsulate everything that he discovered into only one thing,

which later was named "art"-that is, music, architecture,

dance and poetry. They left us with wise sayings about eternity

and the ephemerality of life. A Turkish-Mongolian legend says:

May the words we utter

Be in harmony with our deeds.

May the Gods we create

Always bear witness to these things.

In our language, the word "rassam" (painter) means

a person who can foretell the future. A painter ranks art, his

creative activity, higher than life itself. Art always precedes

science, opening up broad horizons for thinking and enabling

people to understand themselves and their surroundings. It helps

them to see realities that escape the normal glance of the naked

eye. An artist is a prophet. Painting is not a profession; it

is a gift, given by God.

I completely share the opinion that man is responsible for everything

that happens in his life. Man is a victim who, with his death,

makes up for everything in the interminable progress of life.

Again, let me refer to the Turkish Mongolian legend about Gesser

Khan:

Our muscles are a long way

From the joys of life

But nearer than the delight of death.

We start by crawling on a carpet. It is at that time that the

rich variety of colors and the ornaments of carpets become engraved

in our minds, leaving traces on our memories. Who knows, maybe

our way of thinking as artists is shaped from that time?

Painting teaches me to realize the essence of life. Painting

is both insanity and consciousness at the same time. These two

notions, of course, contradict each other-but only at first.

One more thing-a painter needs a long life, but that's an absurd

idea because an artist expends his life, bit by bit, in his works.

He gradually comes to discover certain realities, and thus consumes

his life in his paintings, living in them. The flames in the

painter's heart, which consume him, light the world which in

turn surrounds him.

Influence of Cezanne

Cezanne

led me by the hand to great art. I found well-constructed color,

form and space in his system. With his analytical style, he made

the world more real to me. He didn't substantiate matter-he personified

it. He gave breath to it by revealing its structure. He could

take a common object, penetrate its essence and reveal its relation

to life. Cezanne's constructivism proceeded from the Renaissance

classics' multi-perspective. His color nuances, as Van Gogh put

it, were like Wagner's rich palette of sound. Cezanne

led me by the hand to great art. I found well-constructed color,

form and space in his system. With his analytical style, he made

the world more real to me. He didn't substantiate matter-he personified

it. He gave breath to it by revealing its structure. He could

take a common object, penetrate its essence and reveal its relation

to life. Cezanne's constructivism proceeded from the Renaissance

classics' multi-perspective. His color nuances, as Van Gogh put

it, were like Wagner's rich palette of sound.

In those years, Impressionists were not on display in the museums

of the Soviet Union. I went to the Director of the Hermitage

Museum in Leningrad [now St. Petersburg] and told him that if

he didn't allow me to see Cezanne's works, I was going to kill

him. And so I was shown the works.

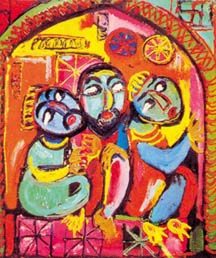

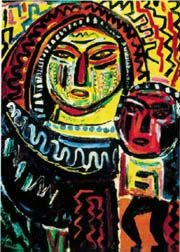

Art:

Javad Mirjavad,

"Madonna", 1987.

Thirty years later, I met Piotrovsky in Baku at an archeology

symposium. He knew about the incident. As he didn't have enough

time to visit my studio, I showed him some photos of my paintings.

He went into raptures and exclaimed: "Babylon! Babylon!

It's great art! It's as great as the pyramids of Egypt. It wasn't

in vain that you aggravated the entire Hermitage!" The incident-like

a page in our lives-reduced us to laughter when we recalled it.

African Art

In 1955, for the first time in my life, I saw a reproduction

of African sculpture [Javad was 32 years old at the time]. I

had never seen such plasticity before-measuring systems opposing

each other, such outbursts of feelings and such strange combinations

of different materials-wood, wisps of grass, natural hair, glass,

bone and fabric. For instance, a human figure carved from ordinary

wood was decorated with glass eyes, natural human teeth, pieces

of cloth, making it look rather extraordinary and mystic-like,

rather Sufi-like, existing as a work of art independent of anyone

or anything in this world. It had a life of its own. The aesthetics

of this extraordinary form of art shook me, dwarfing everything

that I had learned from classic European art, which took its

sources of cultural tradition from Mediterranean cultural aesthetics.

To become more familiar with African culture, I often frequented

the public library in Moscow and read many books. But even all

this did not satisfy my thirst. I arranged to go to Leningrad

to visit the Museum of World Ethnography. There I saw African

figures carved from wood, Benin's bronze heads, women's faces,

plainer than reality and women's eyes-wide-open in amazement,

or was it horror? I couldn't keep myself from touching them.

Behind those prominent eyes, I saw man's passionate eagerness

to burst forth beyond his physical confines, to free himself

and merge with the universe. There I also saw the stone statues

of the Oceanic countries, Siberian masks used in shamans' rituals,

Burmese figures, three meters in height, and examples from the

school of Indonesian painting. At that time, an exhibition of

Tibetan icons also opened in Leningrad.

It was as if, finally, I had found myself in a mysterious world

of colors, for which I had been longing for thousands of years!

I went out and bought watercolors and paper and started working.

For days, I worked from morning till night, making sketches,

going through about a hundred pages of Whatman paper.

I returned to Moscow from Leningrad and again headed down to

the public library. There I viewed reproductions of Ajantan's

frescoes [Buddhist rock-cut cave temples and monasteries in western

India], and Central Asian as well as Southeast Asian samples

of art. Again more faces and images. About that time, there was

an exhibition of Mexican art in Moscow. I became fascinated in

their ancient stone sculpture and in the work of contemporary

artists Tamayo [born 1899] and Sikeyros.

Breaking from Tradition

Then I returned to Baku. Again, back to the village of Buzovna

near Baku. I was completely alone for ten years. That's when

I decided to break from European tradition completely. It seemed

all dried up and emaciated and no longer satisfied me. I started

to destroy my paintings and by the time I finished, not a single

canvas was left. I was 35 at the time. I remember thinking that

when Van Gogh had been my age, he had already created all of

his works and was already dead. But I had done nothing yet and

it frightened me. I became very depressed.

I had started painting as had others, early in my youth. So when

I destroyed all my paintings, I had already produced some good

works but not even those were spared from the fire.

I'm not sorry for having destroyed them, though it was wrong

of me. I only regret that I destroyed a different style that

I had created.

Deep passions desperately tore at my inner world affecting my

psyche. I remember walking around like a madman. I had grown

into someone impossible to get along with. To calm myself down,

I often thought of what Van Gogh himself had said, "An artist

is a saint, but at the same time, he's somewhat of a rabid dog."

This process-or metamorphosis-or conversion-must be familiar

to every creative man.

Gobustan

Like all of mankind, I began my path in art from nothing. Gobustan-the

residence of primitive man from the Paleolithic, Mesozoic and

Neolithic periods-became the starting point of my path (1956-57).

Frankly speaking, I didn't so much like the carvings that I saw

in Gobustan; they had looked so much better in reproductions.

But the fear of wild animals, drawn by primitive man, produced

an impression of physical strength.

The site itself was fantastic-mountains and rocks of various

shapes that had undergone tremendous transformation by the winds

even before history had been recorded. I've tried to portray

the spirit of those rocks, volcanoes and mountains, and the dynamic

naturalness of their form. Personally, I've always viewed nature

as the primordial form of existence. I have even felt resentful

that primitive man seemed indifferent to nature.

It was the primitive arts of Gobustan that laid the foundation

of the Middle Ages miniature and plastic arts in terms of its

forms, composition and harmony. I was particularly impressed

by the art of the Neolithic period and those of periods closer

to us. The culture of those ages is very well represented in

the region of Azerbaijan. The primitive artist, not deprived

of the Sufi and abstract way of thinking, skillfully used stone

to create brilliant forms.

While in Buzovna, I produced some women's images on large wooden

boards using tar and enamel. Sometimes I would model different

pictures on a sandy surface, cover them with tar and then decorate

them with pebbles, wood and metal. Sometimes, I would mold various

figures from cement. It was abstract art and did not bear even

the slightest resemblance to European abstract art. I had made

them in nature in the open air in the midst of a strong impulsive

storm of emotions. All those works contained a monumental form

and rich color scheme.

It's a great pity that these works didn't survive-except for

three of them. The boards couldn't bear their weight and broke

while they were being transported to another place. The paint

on some of them cracked and came off, and the tar spoiled the

paint and sometimes cracked and peeled. Some of them were too

heavy for us to carry while moving from one place to another.

As it was impossible to lift them, we buried them and I drew

a map to mark the spot where they were hidden. But alas, I lost

the map. Thus, the destruction of those works was brought about

by my poverty.

The vivaciousness of youth gives rise to the crazy impulse to

perceive everything, to comprehend everything and to taste everything.

Sometimes it is our inexperience that causes us to rise up and

rebel against all the things that seem unfair and unjust in life.

But as time passes and we become more mature and wise about life,

through experiences-both painful and fortunate-we gradually come

to realize that it is not the world that is imperfect or impotent

in the face of the inexplicable mysteries of the universe, but

it is our knowledge that is not profound enough to perceive these

mysteries.

Rooted in the Land

For me, the Absheron Peninsula, especially the part known as

Gobustan, is a sacred place-a kind of shrine. I'm not saying

this because it is the place where I first opened my eyes to

see the sky. Nor is it because in this small area, you can find

sea, mountains, deserts, volcanoes, temples and ancient graveyards

[Sufi Hamid cemetery] in harmony with each other. Once a Mexican

archeologist reported on this theme and observed: "One can

sense hope for life in those graves, even after death."

Those words are very close to the spirit of my memories about

Absheron. Primitive man lived here and left us pictures for us

to remember him by. But in addition to all this, the most important

thing about this land is its unconquerable spirit. I've roamed

all around and know every inch of this land. It is this land

that has made me an artist and given me patience, fortitude and

loyalty. It is this land that has forged me into the artist that

I have become.

Zardusht [founder of Zoroastrianism, 628-550 B.C.] used to live

here. He left us with songs, tales, stories and legends saturated

with his wisdom. Our people, generation after generation, have

been brought up and educated in this heritage. These people have

always concerned themselves with everything happening in this

world. These people have never stood by and just watched while

important things were happening.

I remember one summer in my childhood, my grandfather, brother

and I were walking to a village. The weather was very hot, as

is usual at that time of year. The vacant fields around us stretched

endlessly. Though we caught a glimpse of a cart in the distance,

it soon disappeared behind the hills. We had walked a long way

under the red, hot, scorching sun when suddenly we saw some watermelons

lying in the middle of the road. We were puzzled. How did these

melons, enveloped in what seemed to be a flaming light, appear

there when all around us was nothing but the throbbing heat?

My grandfather said that the cart owner must have had something

to do with it-that it was his handiwork. Seeing us in the distance,

he must have left the watermelons on the road to make the children

happy.

I will never forget the warmth, the color and the taste of those

watermelon slices that my grandfather cut for us. Nor will I

ever forget that cart owner-even though I have never seen his

face.

This is the first, and most likely the last time that I will

take up my pen to create "literature". Honestly speaking,

this work is not for me.

There is a legend in Ramayan about people gathering wheat left

after it has been harvested. The legend says that these people

gradually melt into the horizon, merging with the sun. In the

end, they themselves turn into the sun. Of course, this is all

meant to be symbolic.

My art is polyphonic-polysemantic and multi-colored. This all

proceeds from my healthy way of thinking and perhaps, from perceiving

the world as a more beautiful place than it actually is. My art

consists of ardent power to perceive the integrity of life and

a healthy bio-psychology. I've always longed to reach the depths

of knowledge so that I might realize something out of these mysteries

of the universe that are beyond human understanding.

Footnotes:

1 Absheron Peninsula is the region where Baku is loca-ted.

The peninsula is sometimes referred to as the head of the eagle

on the Azerbaijan map. As it is surrounded by the Caspian Sea

on three sides, the winds can be ferocious and hence the word

for "Baku" meaning "wind beaten".

2 Tofig, Javad's brother, had poor eyesight and walked onto

some train tracks and was killed in Moscow by an oncoming train.

3 Gobustan is about an hour's distance west of Baku. It identifies

the region where there are ancient cave drawings that date back

at least 5,000 years.

Javad's wife

may be reached in Baku at (99-412) 39-68-24.

Translated

from Azeri (Cyrillic) by Tamam Bayatly from the journal Ganjlik

(February 1988, 21-24).

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.2) Summer1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.2 (Summer 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of

Cezanne

led me by the hand to great art. I found well-constructed color,

form and space in his system. With his analytical style, he made

the world more real to me. He didn't substantiate matter-he personified

it. He gave breath to it by revealing its structure. He could

take a common object, penetrate its essence and reveal its relation

to life. Cezanne's constructivism proceeded from the Renaissance

classics' multi-perspective. His color nuances, as Van Gogh put

it, were like Wagner's rich palette of sound.

Cezanne

led me by the hand to great art. I found well-constructed color,

form and space in his system. With his analytical style, he made

the world more real to me. He didn't substantiate matter-he personified

it. He gave breath to it by revealing its structure. He could

take a common object, penetrate its essence and reveal its relation

to life. Cezanne's constructivism proceeded from the Renaissance

classics' multi-perspective. His color nuances, as Van Gogh put

it, were like Wagner's rich palette of sound.