|

Summer

1999 (7.2)

Page

19

Rasim Babayev

(1926-2007)

The World

of Divs and Angels

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Rasim Babayev

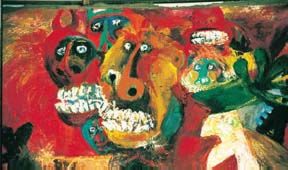

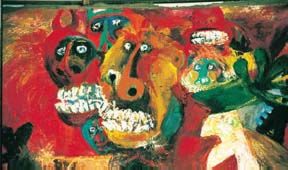

Many of Rasim Babayev's

paintings seem like they belong in a fairy-tale collection designed

to trigger nightmares. He's known for drawing many-fingered,

many-legged and many-headed horned monsters baring several sets

of teeth, which threaten tiny, helpless humans. The white teeth

stand out in stark contrast against dark purples, blues and splashes

of crimson. But these monsters, known as "Divs" ("devils"

in Azerbaijani fairy tales), are not just imaginary. Many of Rasim Babayev's

paintings seem like they belong in a fairy-tale collection designed

to trigger nightmares. He's known for drawing many-fingered,

many-legged and many-headed horned monsters baring several sets

of teeth, which threaten tiny, helpless humans. The white teeth

stand out in stark contrast against dark purples, blues and splashes

of crimson. But these monsters, known as "Divs" ("devils"

in Azerbaijani fairy tales), are not just imaginary.

According to Rasim, they symbolize totalitarianism, specifically

the terror of the Soviet system. Despite the ban on any artistic

expression that did not reflect "Social Realism", Rasim

managed to get away with depicting them on his canvases under

the guise of "Primitivism". In a recent interview with

our staff, he described the circumstances that led him to paint

Divs, and now to even include angels on his canvases, as Azerbaijan

begins its journey towards independence.

_____

I began studying in Moscow's Art Institute in 1949. When I was

a third-year student, I made a painting of my brother and a few

of his friends down by the sea. There was much that was different

about that work. The colors were not conventional; also, the

body lines of my figures were not realistic.

When I presented the painting to the Institute's Committee, they

looked at it but wouldn't give me a grade for it. Later, the

secretary came and asked me to pay a visit to Rector Madorov's

office. When I did, I found several other professors gathered

in his study as well. They reproached me: "What have you

done, Babayev? This is not what we call art. Why have you gone

down the wrong path? You studied so well your first year. You

were an excellent student-what has happened to you?"

One of the professors asked me: "Where could you possibly

have seen a sea that was this color?"

I replied, "I wonder if you've ever seen our sea?"

He said that yes, he had been to Baku and yes, he had seen the

Caspian Sea.

I told him, "But you haven't looked at our sea with my eyes.

If a hundred men describe a certain object, each one will describe

it in his own way."

I was asked to leave

the room and wait out in the corridor while they continued discussing

my work. Then Professor Nevejny came out of the study and tried

to console me: "Take it easy-things like this happen. I

know that the 1930s have had a negative influence on you [referring

to the Stalinist repression] and now you are being influenced

by the West. You'll soon get over it and forget about all these

things." I was asked to leave

the room and wait out in the corridor while they continued discussing

my work. Then Professor Nevejny came out of the study and tried

to console me: "Take it easy-things like this happen. I

know that the 1930s have had a negative influence on you [referring

to the Stalinist repression] and now you are being influenced

by the West. You'll soon get over it and forget about all these

things."

They were about to throw me out of the university. For some reason,

they didn't. After that incident, the professors picked on me.

Once the Rector told me, "You can't paint. You just spread

the colors around and don't actually show what you are trying

to represent."

More Trouble

When I was due to graduate, the Committee refused to give me

my diploma because they didn't like my final project, a painting

called "Fishermen." I had painted the fisheries I had

seen in Salyan [a region in Azerbaijan located on the northern

coast of the Caspian Sea]. They looked at the work and said that

they couldn't accept it because the people looked like Americans,

not Soviets. I told them that I had never been to America or

laid eyes on an American except in a few American movies. I was

supposed to get my diploma the following day, but they refused

to give it to me.

In 1964, an Artists' All-Union Congress was held here in Baku.

When I ran into the Institute's Rector who had come from Moscow,

he paused and told me, "If my memory serves me right, you

have yet to receive your diploma." I admitted that he was

right - no, I didn't have my diploma. By that time I had become

an official member not only of the Artists' Union in Azerbaijan

but of the Artists' Union of the USSR as well, so he suggested

that I go and pick up my diploma. But I told him: "You can

keep my diploma. I give it to you. I don't need it anymore."

And I didn't.

When I first started studying art, I didn't understand the deficiencies

of the Soviet system. It was as if I was wandering in a daze.

In 1950, as a first-year student in Moscow, I visited the Pushkin

Fine Arts Museum nearly every day. There the works of world-renowned

artists such as Rembrandt, Gustave Courbet, Michelangelo and

Rafael inspired me tremendously. Of course, many of the works

were copies, although there were some originals as well. Still,

it was a revelation to me to see them.

But later that year a very strange thing happened: the museum

was closed in preparation for Stalin's 70th Jubilee [birthday

celebration]. The museum's art was replaced by an exhibition

displaying the personal gifts that Stalin had received. This

absurdity angered me and I trace my awakening and the beginnings

of my protests against the Soviet system to that event.

After I left the university, I worked in Moscow for a year, but

soon realizing that Moscow was not the right place for me, I

returned to Baku.

20th Century Art in Azerbaijan 20th Century Art in Azerbaijan

During the 20th century, Azerbaijani art has been influenced

by various schools of art. At the beginning of this century,

two German artists came to Baku - Otto Schmerling and Rotter.

They did graphics plus a lot of other work for Molla Nasraddin,

a magazine of political satire [1906-1931].

Azim Azimzade, the man for whom the major art school in Baku

is named, was also creating at the time. He was a great artist.

I only had the chance to watch him draw once - it was on TV.

His method was amazing. He drew one line, and then another. After

two to three lines, an image appeared of a woman wearing a chador

[veil]. Even though Azimzade never received any special training,

he was considered one of the founders of formal painting in Azerbaijan.

Then there was Bahruz Kangarli. He was an educated artist, having

studied at the Tbilisi Academy. There were also a lot of Russian

and Ukrainian artists in Baku (Gerasimov, Plaksin, Karganov,

etc.)

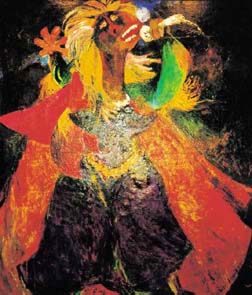

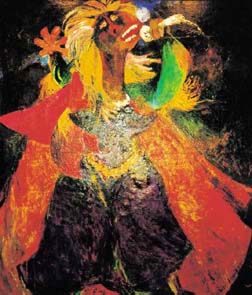

Rasim Babayev, "The Opera Singer", 82.5" x

73.5", oil on canvas, 1953. Courtesy: private collection

of Farhad Azima of Kansas City.

In the 1930s, an art college was established in Baku upon the

initiative of Azim Azimzade. Its graduates included outstanding

figures such as Tagi Tagiyev, Kamil Khanlarov, Boyukagha Mirzazade,

Mikayil Abdullayev, Sattar Bahlulzade, Maral Rahmanzade, Vajiha

Samadova and Rustam Mustafayev.

Some of them continued their education at the Moscow Art Institute,

for example, Bahlulzade, Rahmanzade, Abdullayev, Tagiyev, along

with Baba Aliyev, Aliagha Mammadov, Yusif Agayev and Alakbar

Rezaguliyev. (Some of them had their education interrupted because

of the war.) At that time, famous artists such as Favorski, Istomin

and Grabar taught there.

In turn, the graduates from that Institute brought the traditions

of Russian art to Azerbaijan. Mainly, art was developing in the

direction of Social Realism. But there was still some influence

from Russian avant-gardism.

Avant-Gardism

Russian avant-gardism

was itself a very interesting phenomenon. I would not say that

it emerged in the Russian culture naturally. It wasn't "cooked".

It came as a revolution rather than evolving out of the culture.

When I was in France visiting the Museum of Impressionist Art,

I studied the trends in French art during the 18th and 19th centuries

and realized that they were linked continuously in their development

like a chain. There was a succession. In Russian art, it was

more like an abrupt jump. Russian avant-gardism

was itself a very interesting phenomenon. I would not say that

it emerged in the Russian culture naturally. It wasn't "cooked".

It came as a revolution rather than evolving out of the culture.

When I was in France visiting the Museum of Impressionist Art,

I studied the trends in French art during the 18th and 19th centuries

and realized that they were linked continuously in their development

like a chain. There was a succession. In Russian art, it was

more like an abrupt jump.

Beginning in 1910, two Russian Maecenases - Shukin and Morozov

- went to Europe and bought a lot of artwork by artists such

as Modigliani, Picasso, Cézanne and Monet. The Russian

school, including avant-garde artists such as Malevich and Kandinsky,

was deeply influenced by these new trends.

Rasim Babayev, "Refugees in their Home", 90 x 90

cm, oil on canvas, 1992. Note the artist's depiction of the refugees'

isolation, anonymity and confinement in their new reduced status.

The multiple feet on each figure reflect the literal translation

of the word, "refugee"- which means "runner"

in Azeri.

The emergence of avant-gardism appeared suddenly in Azerbaijan's

art just as it did in Russia. Artists representing avant-gardism

were not consciously doing it-they just did it because they liked

it. There was no philosophy behind their work. (Art with philosophy

behind it didn't emerge in Azerbaijan until after the war.) This

avant-garde trend was quickly transformed into Social Realism.

New Generations

My art

education began in Baku in 1945 prior to my going to Moscow.

Those of us artists who were against the system formed a group

that included Ernest Neizvestny, Kalinovsky, Monashkina, Gorkhmaz

Afandiyev, Tofig Javadov and his brother Javad Mirjavad. That

was the beginning of our "dissidence". We all gathered

around one single idea, it was the idea that we all disagreed

with the Soviet school of art-that is, Social Realism.

At the time, we were being trained by teachers who had been educated

in Russian art schools. The characteristic feature of the Russian

school was "draw what you see". There was a photo effect

in all of the works. Plus the themes were almost always ideologically

motivated: collective farms, Oil Rocks (the piers built out over

the Caspian off Baku's shore to extract offshore oil), plants,

factories, etc.

Our generation did not agree with this ideology. It showed in

our works, most of which were influenced by Cézanne. We

deviated from the photo effect in both form and color.

In the 1950s, I began working with Javad Mirjavad and his brother

Tofig Javadov in Buzovna [a district in Baku]. The Artists' Union

was suspicious of us. They wondered what we were doing, why we

hung around together so closely. They wanted to disband our group

and get us to join the Union. We were considered dangerous. (We

were not officially told this, but that was the rumor that was

flying around.)

Another group of dissident artists returned from Moscow during

the 1960s, which included Gorkhmaz Afandiyev, Nazim Rahmanov,

Kamal Ahmad and Hamza Abdullayev. They returned to Baku during

the period known as "the thaw"-Khrushchev's era, when

there were not so many restrictions on artists as Stalin had

imposed. These young artists came to Buzovna frequently. It was

like they were being spiritually fed there. They made their living

from orders by the government-doing placards and posters and

such things-but that was just to earn money. I remember that

it was during this time that Togrul Narimanbeyov began his creative

works.

Primitivism

After living in Buzovna

for a while, I couldn't work with Javad and Tofig anymore because

we disagreed so much about colors. I would say, "We have

to put this color here," but Javad would say, "No,

another." So in May 1958, I decided to head for Shaki, a

charming town and one of Azerbaijan's most ancient communities.

It's located in the foothills of the Caucasus, about a five-hour

journey west of Baku. After living in Buzovna

for a while, I couldn't work with Javad and Tofig anymore because

we disagreed so much about colors. I would say, "We have

to put this color here," but Javad would say, "No,

another." So in May 1958, I decided to head for Shaki, a

charming town and one of Azerbaijan's most ancient communities.

It's located in the foothills of the Caucasus, about a five-hour

journey west of Baku.

Rasim Babayev, "Divs", 1981-82.

I was very impressed by the Shaki Khans' Palace there [built

in 1762]; it became like a new art school for me. It was there

that I got to know myself-I finally understood who I was, where

I had come from and why. The Shaki Khans' Palace is a pure Azerbaijani

school-there is Azeri philosophy inside it. I stayed there for

six months.

At the time, the palace was in very bad need of repair: it had

no ceiling, the murals were spoiled and children were building

fires inside the building. Later, it was repaired, but during

my stay, I managed to copy nearly all of the murals. The primitivism

in my works originates from there, from those medieval paintings.

Then I returned to Baku and began working with Javad again. He

was a close friend of mine, even though we quarreled from time

to time. I had known him since childhood. Javad was a bit older

than I was. We used to wander all around the city together. We

walked all over the Absheron Peninsula from Gobustan to Sumgayit.

As with many other artists, Absheron has deeply influenced my

work.

The Div

Then I began working in another direction. In the early 1960s,

I was asked to illustrate a book called "Jirtdan."

That was where I met the Div. ["Jirtdan" is one of

Azerbaijan's most popular fairy tales. It features a small boy

who outwits an evil "Div". In the book, the Div is

a hairy, frightening monster who loves to eat children. See "Children's

Folklore," AI 4.3, Autumn 1996.]

After that, the Div became a symbol of evil in my paintings-the

symbol of dictatorship. This Div began to develop gradually;

it became the many-headed Div, the many-handed Div, the many-legged

Div and so on. The symbol of the Div appears again and again

in fairy tales and folklore. This Div still appears in my work,

since dictators still exist in the world today.

What else do I paint besides Divs? In 1990, I had an operation

and was kept under sedation during the procedure. While I was

asleep, I dreamed of angels. Yes-two white, real angels. Now

these angels appear in my work.

When I compare the past and today, I can say that back then I

could never have imagined that someday I would be painting angels.

We used to be under so much pressure that I dedicated all my

works to the collapse of the Soviet Empire. Today we have no

such pressure. In the past, any works that were against government

policy were never allowed to be exhibited.

Appeasing the KGB

In 1976, I had a personal

exhibition in Moscow. When I went to the area where the exhibition

was to take place, I saw a man with dark glasses standing in

front of my paintings, looking at them. I discovered that he

was a KGB agent who had been sent to look at my works and decide

which ones should be taken away. In 1976, I had a personal

exhibition in Moscow. When I went to the area where the exhibition

was to take place, I saw a man with dark glasses standing in

front of my paintings, looking at them. I discovered that he

was a KGB agent who had been sent to look at my works and decide

which ones should be taken away.

When I realized that the opening of my exhibition was deliberately

being delayed, I asked what was wrong. I was told that there

had been some confusion, and that someone from the Artists' Union

would be contacting me. So a guy came over to me (by the way,

I knew him well; he was a good art critic). He told me that I

had to take away nine works including the ones entitled "Idiot,"

"Aggression," "Hysteria" and "Extremists".

Rasim Babayev, "Camel", 59 x 84 cm, pastel on paper,

1989.

Farhad Khalilov (now President of the Artists' Union in Azerbaijan)

was there with me. He objected: "Oh, no, we won't take them

away." (Farhad was also one of those against the system.)

But I realized that unless I took them away, they wouldn't open

the exhibition. So I complied.

Before those works were taken away, I told the art official,

"If the mighty Soviet state is afraid of these little works,

then take them away." But he ignored my words. I had organized

40 works for the exhibition; nine of them were excluded.

I used to wonder why so many artists immigrated to Paris, but

then it became clear to me. It was because art was more independent

there-far removed from politics. Politics doesn't oppress art

there-something quite different from what we were experiencing.

During the Soviet period, we had to rise against the system in

order to make art independent from it. Today, art is free and

independent. If someone is a genuine artist, he can take advantage

of this freedom. Being an artist is like being a volcano, if

you're able to erupt, then do it; if not, then keep silent.

For more

photos of Rasim's work, see "Rasim

Babayev"

[AI 3.1, Spring 1995], AI

covers for 4.3 (Autumn

1996)

and 6.2 (Summer

1998)

as well as the illustrations in Vagif Samadoglu's article "The

Sixties: A Roadmap to Independence" [AI 6.1, Spring 1998].

Rasim Babayev's studio is near the Hyatt Regency. He can be reached

at Tel: (994-12) 38-47-82 (studio) or 38-22-87 (home).

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.2) Summer1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.2 (Summer 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

20th Century Art in Azerbaijan

20th Century Art in Azerbaijan