|

Six Years and

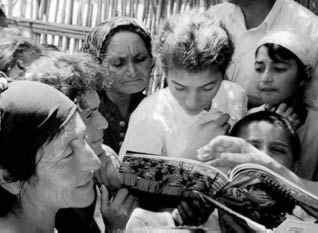

Counting Pari Guliyeva (1961- ) and her family fled their home in Zangilan near the Iranian border in 1993 after their village was attacked by Armenians. She and her husband Eyvaz Jamalov (1960- ) have lived with their daughter Khumar (age 13) and son Orkhan (age 9) in a refugee camp since October 25, 1993. In a recent interview, Pari described their perilous flight from home and told us what it's been like to eke out an existence, living in a refugee camp since 1993. _____

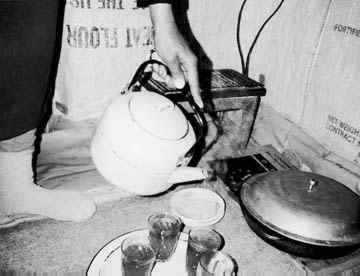

Life in the Camp I'm living in a refugee camp with my family now. It's the largest camp in the country-Sabirabad Camp No. 1. Nearly 10,000 refugees live here. We've been here since 1993 when they first started putting up the tents. Now most of us have managed to build rather crude mud brick huts with one or two rooms. The floor is earthen. We've covered it with plastic sheets and a blanket, but in winter, it's still so cold. In summer, it's exhaustingly hot in Sabirabad and our shelters have so little ventilation. It's like living in a desert. Then there's mosquitoes and malaria, which is indigenous to the region. It's so hard to live without running water and basic household items in the camp, especially since we were used to having our own kitchens and bathrooms. We cling to the hope that one day we will have a chance to breathe our native air again. My biggest dream in life is to bring up my children well, to give them a quality education so that they can be happy in the future, and to die in the native country where I was born. As I mentioned earlier, we fled our home without finding my husband. After two days of separation, we finally found each other again on the other side of the border in Iran. He had swum across the Araz River. To tell you the truth, I didn't recognize him-he had changed so much. He looked like a 60-year-old man. Somehow, he had suffered a severe shock. He had become mute, we suppose out of fear. He was unable to speak to anyone. We think maybe he had been beaten and tortured, but to this day he still can't tell us. After we came to the refugee camp, my husband had an operation and was in the hospital for five months. He has recovered a bit, but still he can hardly explain anything. When he gets nervous or excited, he panics and becomes mute again, unable to speak until he calms down. Barely Surviving Here in the camp, we have enormous problems. It's not an exaggeration to say that we are barely surviving. People in the camps are starving. Believe it or not, it's been worse this summer. In the past, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent used to help us. We used to receive 15,000 manats (about $3.50) per person each month. It wasn't even enough money to buy bread. But now the aid has diminished dramatically. It seems much of the international humanitarian aid is being directed to Kosovo these days.3 We used to be given oil and flour, too. There's a cotton field in Sabirabad where we go and work. Obviously, not all of the people in the camp can work there, even though they all need jobs. To qualify for such hard labor, you need to be young, healthy and lucky enough to find an employer who needs you. For all our hard labor, we barely get any money. Some people haven't even been paid by the local government since last year. But this year they promised to pay us a sack of wheat at the end of summer-that's all. Of course, some people aren't able to work. They wait for someone to give them at least a loaf of old bread. But of course, they're too proud ever to beg for anything from anyone. Everyone here knows everybody's situation since we live so close together and we all try to do our best for each other. For the past three years, we haven't eaten any meat. And there's been so few fruits and vegetables. You can't imagine the pain I feel as a parent when my children ask for something to eat, and I don't have anything to give them. This summer, our diet consists mostly of tomatoes-we eat tomatoes for breakfast, tomatoes for lunch and tomatoes for supper. Unfortunately, the difficulties don't end when you find a way to get the tomatoes. It doesn't take long to develop stomach problems when you're only eating tomatoes for every meal. They're so acidic. But what can we do? Those who don't manage to get tomatoes are starving. We don't know what tomorrow will bring. Each day gets worse and worse. We have just one hope, and that is that one day we will go back to our native land and begin our lives anew-the happy lives that we were living before all of these troubles started. Footnotes:

|