|

Winter

1999 (7.4) Sing Tar, Sing Ramiz Guliyev

(1947- ) is unequaled as a tar player in contemporary Azerbaijan.

This past year, Ramiz was onstage, playing as usual: eyes shut,

tar clutched against his chest, totally concentrated on the music.

Suddenly, the instrument snapped and broke - right in the middle

of a concert. It came as a shock, but no one was actually surprised

because Ramiz always plays with such intensity.

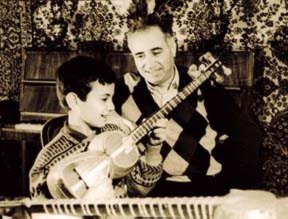

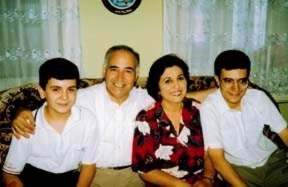

Photos: Performing tar duo at the Third International Film Festival in Baku (October 1999). Ramiz Guliyev (left) and his son Ayyub (right). The Gara Garayev Chamber Orchestra accompanied them. Teymur Goychayev, conductor (background at right photo). When Ayyub was very young, it became obvious to his father that he, too, was interested in the tar. "When he was born, I understood that he was a very intelligent child because he was very naughty and mischievous," says Ramiz. A mystery soon developed in the Guliyev household. When Ramiz would come home from work each day, he could sense that someone had been touching his tar. Sometimes the case was left half-closed or the tar wasn't in the exact position where it had been left. His wife insisted that she hadn't touched it, but recalled that Ayyub, 2, would often go into that room and become very quiet. Ramiz soon realized that it was his son who had been opening the tar case. Hoping not to get caught, the child had sensed when his father would be returning home and tried to remember to close the case, but sometimes he forgot. Soon Ramiz found an antique baby-sized tar and started teaching Ayyub how to play. Ayyub has since grown up to become an accomplished tar player just like his father. The two of them often perform duets together at some of the most prestigious concerts in Baku. For example, in 1997, when the world-famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich returned to his native Baku for his 70th birthday, Ramiz and Ayyub were invited to play at his Jubilee concert. Their performance was so extraordinary that the cellist invited them to perform at his birthday celebration the following week at the Music Conservatory in Moscow. Starting Out  Photo: Ayyub Guliyev competing in the Annual Tar Competition at the Music Academy where he took First Place, 1997. But Ramiz already had conceived of an alternative. "We had a beehive," he says. "I promised my father that if he bought me the tar, I would learn to play it 'sweeter than honey'. So dad gave in, sold the hive and I got my wish - a new tar." Ramiz began studying at the music school in Aghdam in the late 1950s. His teachers realized that he was a promising student and pushed him hard, insisting that he stay long hours after class to tutor other students. They threatened that if the other students didn't do well, he would get a bad grade, too. At 14, Ramiz joined the Shur Ensemble that was invited to perform in Moscow and various regions of the Soviet Union. Then he went on to study and graduate from Baku's Music Conservatory (now Academy). Today Ramiz heads the Department of National Musical Instruments at the Academy, which includes 30 professors and approximately 100 students. He has written several authoritative works describing the techniques of tar playing, as he feels it's his duty to future generations. Many books and materials are imported for students of Western classical music, but so little material exists for those studying traditional instruments. "If there are no materials," Ramiz says, "the art can't develop. I take the works of Azerbaijani and foreign composers and edit them for tar, kamancha and other traditional instruments." He's especially proud of his three-volume set for tar and piano, which includes 100 pieces by Azerbaijani composers. Despite the scarcity of textbooks, Ramiz says that the quality of playing in Azerbaijan has reached a very high level. More than 20 concertos exist for tar, written by composers such as Haji Khanmammadov, Said Rustamov, Suleyman Alasgarov, Tofig Bakikhanov and Jahangir Jahangirov. Love Affair with the Tar  "There are two kinds of performances, one stemming from improvisational playing, the other from note-reading. It's very difficult to excel at both. You need to be able to speak the language of each genre. If you're playing Verdi, Beethoven or Mozart, then your instrument must express that language. When you switch to traditional mughams, an improvisational language, it requires an entirely different thought process. One's inner world, one's feelings, the left hand, the right hand, the mind, the soul - they're all inter-related. Leave one element out and the mugham performance suffers. Photo: The Guliyev Family: Ayyub, Ramiz, Hokuma and Emin in 1997. "Always you have to make your instrument be subordinate and obey you. It's has to be afraid of you. You have to carry on a dialogue with it." Ramiz speaks about the task of the performer in front of an audience. "If you can manage to amaze the audience, then you're really a good musician. There are so many kinds of people and so many audiences. A performer has only a few moments to gather all those people together and immerse them into the world of music. A truly great musician can succeed in making people, even those unfamiliar with the genre, fall in love with his works." Passing the Torch Whereas Ramiz had a lot of obstacles to overcome, Ayyub has benefited from his father's encouragement and mastery of the instrument. Ayyub remembers writing out a practice schedule for himself and asking his father to practice with him and give him a grade. When he was seven or eight years old, he started writing music for both tar and piano. "They were short pieces and not very professional," Ayyub admits, "but I took such an interest in doing it." In 1997, Ayyub won First Prize at the National Competition of Traditional Instruments at the Academy of Music. He also was honored with President Aliyev's Golden Book of Young Talents, which means that he receives a $250 stipend from the government each month, a substantial sum given that governmental salaries are usually less than the equivalent of $50. Ayyub's talent and hard work have earned him early admission into Baku's Academy of Music - a rare privilege that had to be approved by Azerbaijan's Minister of Education. This enabled him to skip his final year (Grade 11) at Bulbul Music School. At age 15, he studies music history, harmony, sight-reading and mugham at the Academy. He's pursuing a double major in tar and conducting. Ayyub admires conductors such as Eugen Mravensky, Claudio Abbado, Herbert von Karajan and Bernard Haitink. His all-time favorite is the Azerbaijani conductor Niyazi (1912-1984), who is considered to be the founder of the conducting school in Azerbaijan. Ayyub appreciates Niyazi's unique talent in synthesizing Azerbaijani national music with Western symphonic music. [See "Niyazi: The Maestro" in AI 5.4, Winter 1997.] Double Play Ayyub began performing tar duets with his father when he was just seven years old. Their first duo appearance was with the State Chamber Orchestra named after Gara Garayev. They performed two works by Azer Rezayev: Gaytaghi (an Azeri national dance) and Dushunja (Meditation). Ramiz says it was hard to prepare for the performance. After the concert, some friends who didn't know much about music congratulated Ayyub for doing half of his father's work. "They had no idea how difficult it was for us," he recalls. Despite the effort, Ramiz is glad that he and his son have continued to play duets together. "I think we did the right thing by playing together," he says. "It's as if we are united through this dialogue of instruments. Without even looking at Ayyub, I can feel how he wants me to play the music, and once I play it, I get the response from him that I want. We understand each other perfectly. Music is spiritual food. It's impossible to become satiated. I always hunger for more. When we perform together, we're in an entirely different world." Ayyub agrees, adding, "The depth of feeling is impossible to describe in words. You just have to feel it - especially on Eastern musical instruments." Recordings of

Ramiz' tar performances are available on the CD Anthology, "Classical

Musical of Azerbaijan" on the Concerto and Chamber Orchestra

volumes, produced by Azerbaijan International, sponsored by Amoco

(1997). To hear the samples go to "Music". |