|

Winter

1999 (7.4) Famous People:

Then and Now

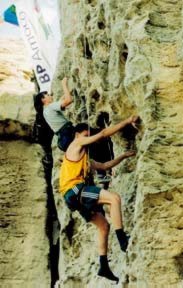

Above: Haji Khanmammadov at age 16 in 1934 and in 1997 Haji Khanmammadov (pronounced ha-JI khan-mam-MA-dov) was born in Darband (now part of the Republic of Dagestan in Russia). He studied composition under Gara Garayev at Baku's Music Conservatory, graduating in 1952. He is known for being the first person ever to write a concerto for the tar, an Azerbaijani traditional stringed instrument. Khanmammadov's music is available on CD from the AI Store, see Classical Music of Azerbaijan (6 volume set). To hear it, click below: Haji Khanmammadov Concerto for Tar and Orchestra (Ramiz Guliyev, Tar) What experiences and interests in childhood would you say shaped your life and career?  In 1932, tragedy struck and my life turned upside down. The Soviets arrested my father and uncle just because they were rich. Father was sent to prison in Darband and my uncle was exiled to Siberia. My mom was left alone to raise five children. After the arrest, one of our neighbors, an old woman, told me: "Get away from here before it's too late. Once they start, they never stop." I wondered where to go and she suggested: "Go to Uzeyir Hajibeyov, the composer of the musical comedy known as 'Mashadi Ibad' (If Not This One, That One). I hear that he's a very kind person. Maybe he will help you." Photo: Free-climbing event for youth sponsored by BP/Amoco, 1999. And so, at the age of 14, my mother gave me money for a train ticket to Baku. Of course, it was difficult for her to let me go off on my own to an unknown city, but there was no other choice. So I bought a ticket and headed to Baku. When the train arrived at the station, I didn't know where to go. Our neighbor had told me to look for Uzeyir Hajibeyov at the Music Conservatory. I got on a tram and asked for directions. When I approached the building, I could hear someone practicing a piano inside. "Uzeyir Hajibeyov is sure to be here," I told myself. At that time, the Music Academy was located at the Music School named after Asaf Zeynalli. Hajibeyov was head of the Traditional Instruments Department. The rector was an Armenian, Anushivan Tergivondian. I went inside and asked directions to Hajibeyov's office. They pointed to the second floor so I went upstairs and knocked at the door. Hajibeyov invited me in. "Muallim (Teacher)," I told him, "I would like to take tar lessons." Hajibeyov wanted to test my innate ability in music. So he played some notes on the piano and I sang them back to him. Then Hajibeyov told me to come back in two weeks and he would try to figure out what to do. I didn't get up to leave and Hajibeyov asked me where I was staying. I explained that I had just come from the railway station. "I don't know where to go from here," I told him. Hajibeyov was very kind. He handed me some money, but seeing me redden, he said, "Don't be embarrassed. Take it. I'll help you, don't worry." So I took the money and he organized a room for me at the school's dormitory. Two weeks later I returned as he had requested and saw a long line of young people waiting to be tested. When my turn came, I went inside and after passing the test, Hajibeyov offered that I should study violin. But I told him that I already knew how to play the tar, but simply that I didn't have one with me. Then one of the other boys lent me a tar so I could demonstrate how I played. Hajibeyov recognized my passion for the instrument and I was enrolled in tar classes with Said Rustamov, who was performing tar in the National Orchestra at that time. I even received a scholarship. Several years later, in 1935, Hajibeyov came to me and offered me a chance to play tar in his opera "Koroghlu" (Son of a Blind Man). The opera turned out to be successful. In 1938, we performed at Azerbaijan's Cultural Festival held in Moscow at the Bolshoi. Stalin liked our performances and even came to see "Koroghlu" and "Arshin Mal Alan" (The Cloth Peddler) two times. When World War II broke out in 1941, Hajibeyov realized that most of his talented students would be drafted and sent to the front. For example, Fikrat Amirov, a student at the Conservatory who later went on to become a distinguished composer, did get called up and soon was severely wounded and had to come back to Baku to recover. Hajibeyov tried hard to keep us at the Conservatory so he organized a special program for composing patriotic war marches figuring that his students wouldn't be sent to war if he could prove their usefulness as composers for the war effort. If Hajibeyov hadn't done this, we might not have had such great composers in Azerbaijan. In 1942, I composed my first song, "Gozal Pari" (Beautiful Fairy). Of course, I first showed it to Hajibeyov. I was so happy that he liked it. The song was performed at the Festival of Transcaucasus held in Georgia that same year. In 1944 we went to Tabriz to perform. While there, Hajibeyov decided to establish a Philharmonic orchestra. So in 1946, when it was ready, I was appointed as artistic leader and Ali Tuda was its director. Hajibeyov died a few years later, in 1948. In 1947 I returned to Baku to the Conservatory. Gara Garayev and Jovdat Hajiyev were both teaching there at the time. I decided to concentrate in two major areas - composition and orchestration - and ended up studying for five years under Garayev's supervision. During my final year, Garayev challenged me to write a tar concerto for my diploma work. He told me, "We've never had a concerto written especially for tar. Why don't you do that for your diploma project?" And so I worked very hard and finished a year later. Garayev liked it and I was happy to be the first person ever to write such a piece. That was 1952. I had to defend my work in front of experts from the Moscow Music Academy. They liked it, too. How was your own childhood different from that of kids growing up today? There's a big difference between the youth of my day and those growing up now. In the past, children showed more respect for teachers, as well as for adults in general. We used to think that teachers were great people. If children don't have this kind of respect, then they won't show an interest in pursuing their education. They won't want to study or learn anything new. In my childhood, children worked harder - they wanted to reach higher levels by studying and working. In comparison, I think today's kids are lazy. But I think many of these problems are due to the economic difficulties in our country. The youth go to the university but after graduating, they can't find any jobs. Why should they study if they aren't appreciated? But they should never give up - they must struggle in life just like we did when we were their age. What advice would you give to young people as they enter the 21st century? They should study more and more to get familiar with new things. They shouldn't be lazy. They should use every moment wisely. What would you say is your greatest achievement in life? What do you want to be remembered for most? I did all that I could for my nation. I wrote five concertos for both tar and symphonic orchestra (1952, 1966, 1973, 1984). I also wrote a concerto for kamancha and one for harp and stringed orchestra. I wrote two musical comedies: "One Minute" (1961), which was in Azeri and "All Husbands Are Good" (1971), which was in Russian. I composed hundreds of songs, most of them sung by the late Shovkat Alakbarova. I especially like to compose music for Mikayil Mushvig's poems (Mushvig was arrested and shot in 1937 during the Stalinist repression), which seem to be like music in themselves when you read them.

|