|

Summer 2000 (8.2)

Pages

36-39

Seaside Boulevard

A Glimpse

Back Through History

by

Fuad Akhundov

Photos: Azerbaijan National Photo and Cinema Archives

"The

Boulevard" is a promenade that runs parallel to Baku's seafront.

This area - popular for strolling and taking in views of the

Caspian - was recently named a national park. Its history goes

back more than 100 years, to a time when oil barons built their

mansions along the Caspian shore and when the seafront was artificially

built up inch by inch. "The

Boulevard" is a promenade that runs parallel to Baku's seafront.

This area - popular for strolling and taking in views of the

Caspian - was recently named a national park. Its history goes

back more than 100 years, to a time when oil barons built their

mansions along the Caspian shore and when the seafront was artificially

built up inch by inch.

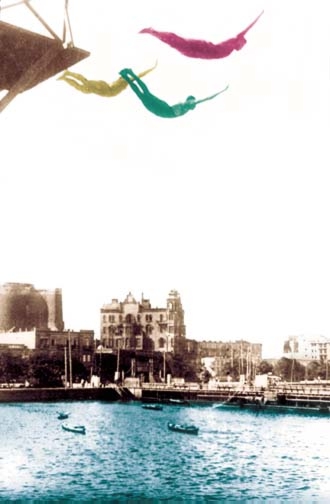

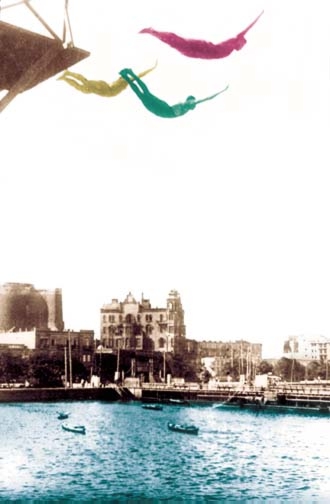

Left: Divers performing at

the Baku Bathing House, early 20th century.

_____

As of 1806, the Maiden's Tower was only 5 to 10 meters away from

the Caspian Sea. However, as the Caspian receded, the land along

its shore was reclaimed. In 1884, the double fortress walls along

the sea surrounding Ichari Shahar (Inner City) were demolished

and construction began on one of Baku's first major avenues,

the Alexandrovskaya Naberezhnaya (Alexandrian Quay), which is

now known as Neftchilar Avenue (Oilmen's Avenue). The avenue

was designed to connect the oilfields in Bibi Heybat (south of

Baku) to the oil refineries in Black Town (to the northwest).

Artificial Seafront

Until the early 20th century, the avenue had mansions on one

side and seafront on the other. There were no trees. Tons and

tons of fertile soil were imported to enrichen the soil quality.

Baku's Mayor, R. R. Hoven, supported by the richest industrialists,

passed a decree in the 1880s saying that all ships entering Baku

harbors from Iran had to bring fertile soil with them. In reality,

this was a kind of "tax" or "duty" imposed

for the right to use the harbor and load up with oil. Within

a very short time, enough soil was deposited, and the parks that

characterize the city's seafront today were developed.

Photo: The sea front before

the Boulevard Park was built up. Maiden's Tower is in background.

In 1900, the Municipal Horticultural Commission decided to plant

trees and shrubs along the seafront. Kazimir Skurevich, a Polish

engineer, designed a 20-meter-wide embankment, using vegetation

that would survive Baku's extremely hot, dry and gusty climate.

The project was placed on reclaimed land near the Mir Babayev

residence (now the SOCAR building).

Photo: Plan for the Boulevard

Park, pre-Soviet period.

The next campaign to improve the Boulevard was launched in 1910

by Mammad Hassan Hajinski, Head of Baku's Municipal Construction

Department. At his urging, the Duma (Municipal Parliament) passed

a resolution to allocate 60,000 rubles to improve the promenade.

Adolph Eykler, a German architect who had also designed Baku's

German Lutheran Church (kirke), was involved in the project.

Photo: Building up the seafront

which is now the SOCAR circle.

Bathing House Built

To select the best design for the Boulevard, Hajinski organized

a contest among the architects in Baku. However, since most of

the city's 30 architects were busy designing mansions for oil

barons, only three submitted plans for it. The winning design

was titled "Zvezda" (Star) and featured a bathing house,

luxurious restaurant and a dozen pavilions. The design specified

that wastewater would be collected in a separate manifold instead

of being discharged directly into the Caspian (which unfortunately

is the case today). Work was completed in 1911.

Photo:

Building

up the quay. Ships coming to Baku to purchase oil were obliged

to exchange shiploads of soil to help build up the sea front.

At the new Baku Bathing House, visitors could take a swim while

visiting the Boulevard. Unfortunately, this bathing house was

closed in the late 1950s due to poor maintenance and the bay's

polluted water.

Photo: Maiden's Tower and

the Hajinski residence (built in 1912).

The improved Boulevard stretched from what is now the SOCAR Circle

to the luxurious cinema, restaurant and the casino that was called

"Phenomenon", designed by Polish architect Joseph K.

Ploshko (1912). During the Soviet period, the casino was converted

to a Children's Puppet Theater, a function it still serves today.

Subsequently, the Boulevard was extended up to the Port Arrival

Station. In the 1980s, the region was more or less mismanaged

and, as is true with most public spaces, maintenance was neglected.

The situation further disintegrated as the level of the sea began

to rise so high that many of the trees and shrubs in the park

started dying off due to the salinity of the water. Now, once

again, the Caspian sea level is going back down. The fact that

the Boulevard has finally been given the status of a National

Park brings hope that gradually the Boulevard will become the

vibrant park that it was originally intended to be more than

a century ago.

Fuad Akhundov, history enthusiast

who wrote this article, specializes in the architecture of early

20th-century Baku. Deep appreciation is also extended to Shamil

Fatullayev, Director of the Institute of Arts & Architecture

at the Academy of Sciences. Photos are courtesy of the National

Archives of Photo and Cinema Documents.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.2) Summer 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.2 (Summer 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|