|

Summer 2000 (8.2)

Pages

72-73

Refugees and

Euphemisms

Forgotten

People - A Borderline Difference

by Richard

Holbrooke U.S. Ambasador to the United Nations

Published in The Washington Post, May 8, 2000; page A23

Reprinted with permission from the author, Richard Holbrooke

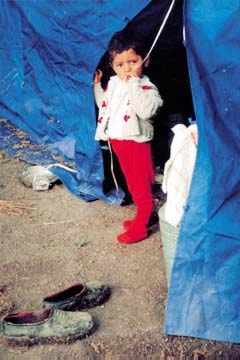

Above: Azerbaijan lost nearly

20 percent of their land to Armenian military occupation beginning

around 1992. As a result nearly 1 million Azerbaijanis have been

left homeless. A ceasefire has been in effect between Azerbaijan

and Armenia since May 1994. Azerbaijanis still want their land

back. Most people who were displaced still live under abominable

conditions. Photo: Oleg Litvin, 1993.

AI Editor:

The majority of Azerbaijan's refugees fall into the category

that U.S. Ambassador Holbrooke describes below. The U.N calls

them "IDPs" - Internally Displaced Persons. Somehow,

it doesn't sound as tragic as the word "refugees".

But hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis were forced to flee

their towns and villages in Karabakh and the surrounding regions

in the early 1990s when Armenians occupied their land by military

force. Helpless, they were left to fend for themselves and find

refuge in other parts of their native land - Azerbaijan.

The personal loss is indescribable. Most of them have lost all

of their personal belongings, their sense of belonging to the

land and community, the graves of their ancestors, their source

of income, their position and role in society. As Holbrooke points

out, they may even suffer more than "official" refugees

do simply because of the way the international community perceives

their situation.

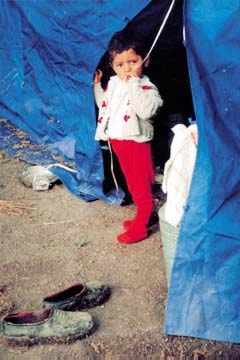

Above: Fleeing in 1993. Photo:

Oleg Litvin

_____

Imagine that you and your family are forced at gunpoint to flee

your home; or that your house is burned to the ground and you

have to go elsewhere for food, water and shelter. You wouldn't

care much where you ended up, as long as it was safe and you

got assistance.

But

there's a catch. If, in your flight, you crossed an international

border, then you became an official refugee, eligible for assistance

from the U.N.'s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). However,

if you stayed within your own country the UNHCR would not take

care of you. But

there's a catch. If, in your flight, you crossed an international

border, then you became an official refugee, eligible for assistance

from the U.N.'s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). However,

if you stayed within your own country the UNHCR would not take

care of you.

You might get some limited international aid, but not much of

it. Your fate would be left in the hands of your government -

even if that government's oppression was the very reason you

fled in the first place, or if the government was unwilling or

unable to allow access. You would be classified by the international

community as an "internally displaced person" - an

IDP - and pretty much ignored.

Of course, there is no real difference between an "official

refugee" and an internally displaced person - especially

to the victim. The sterile and bureaucratic initials IDP have

been enshrined in U.N. and international legal documents, but

they are a euphemism that allows the world to ignore an enormous

problem.

We're talking about a huge number of nearly forgotten people.

Today, there are at least 20 million internal refugees worldwide.

The number of "official" refugees, on the other hand,

has declined steadily since 1992 and now numbers about 11 million.

While both figures are disturbing, the trends clearly have reversed.

In Sudan, for example, nearly 4 million people have been internally

displaced; in Sri Lanka, more than 600,000; in Azerbaijan, more

than a half-million, many of whom live in railroad cars. According

to recent estimates, the Congo has more than a million internal

refugees.

As Julia Taft, Assistant Secretary of State for Population, Refugees

and Migration, has repeatedly noted, the number of internal refugees

has more than doubled during the past two decades. The rise in

these numbers represents a subtle but noticeable shift in geopolitics:

During the Cold War, refugees crossed borders to escape governmental

threats. But conflicts in the 21st century (Chechnya, the Congo,

Angola) are more fractured. Internal refugees in the Congo, for

example, are fleeing a multiplicity of armies from five countries,

as well as an even larger number of rebel movements.

The support the international community provides to such people

is woefully, horribly inadequate. While Sadako Ogata, the dynamic

head of the UNHCR, recently issued a more forward-leaning paper

on internal refugees that acknowledged the "uneven and in

many cases inadequate" response to this issue, humanitarian

aid donors continue to make far fewer resources available to

internal refugees than to others. Non-governmental organizations

and the Red Cross do give some assistance to such refugees, but

they cannot handle the situation alone. Moreover, the U.N. system's

reliance on what is called "coordinated" response all

too often turns out to be another euphemism - for ineffectiveness,

in this case. In bureaucracies, "co-heads" usually

means "no-heads." Victims fall through the cracks.

The primary mandate for internal refugees should be given to

a single agency, presumably the UNHCR. This suggestion has been

criticized by some in the international community as unfair to

other agencies, but no one should be defensive when it comes

to taking action. Criticism ought to be welcomed if it stimulates

reform.

The international community should consider proposals to meet

the following objectives:

- Designate a

lead agency for each internal refugee situation that arises and

clearly define that agency's responsibilities. In most cases,

it will be UNHCR.

- Have all U.N.

humanitarian agencies designate a single point of contact on

internal refugees.

- Keep better

track of these emergencies. For example, the U.N. Secretary General

should issue regular, comprehensive country-by-country reports

on the state of the world's displaced people and what the U.N.

is doing about them.

- Make it clear

that protecting and speaking up for internal refugees is just

as important as making such efforts for "official"

refugees. Unfortunately, some humanitarian and development agencies

still don't seem to see that as part of their mandate.

- Do more to

support the efforts of Francis Deng, the Secretary General's

Special Representative on Internal Refugees, who has played a

seminal and visionary advocacy role. Deng is a part-time, voluntary

employee who receives budgetary support for only a few trips

a year and is dependent upon other U.N. agencies for staff support.

If we can draw

the world's attention to the plight of these people; if we can

pressure governments to protect these innocent victims and secure

access for aid groups; and if we can design assistance programs

around the principles of predictability, accountability and universality

- then we will have taken a major step toward alleviating this

serious problem. We can ignore it no longer.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.2) Summer 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.2 (Summer 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|