|

Voices from

the Ages

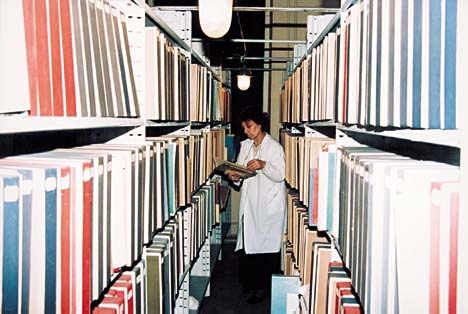

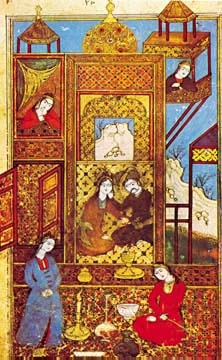

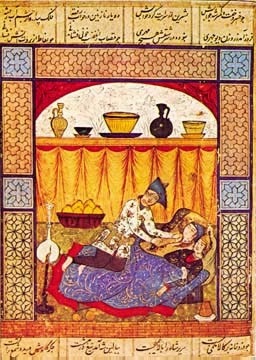

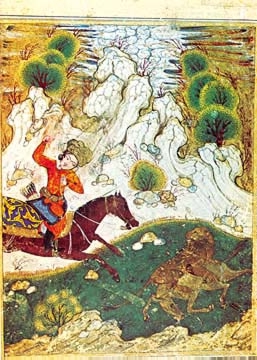

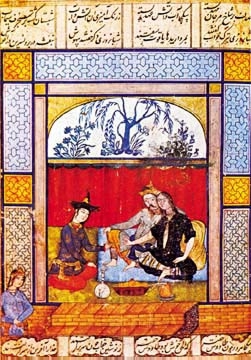

Rare art miniatures preserved at Baku's Manuscript Institute. Left: Miniature from Nizami Ganjavi's "Seven Beauties" (1636). Right: Miniature from Nizami Ganjavi's "Khosrov and Shirin" (1636). Many of the ancient manuscripts found at the Institute came from the private collections of Azerbaijan's most prominent 19th- and early 20th-century thinkers, including Abbasgulu agha Bakikhanov, Mirza Fatali Akhundov, Abdulgani Afandi Khalisagarizada, Husein Afandi Gaibov, Bahman Mirza Gajar and Mir Mohsun Navvab. It continues to collect manuscripts, rare books and historical documents from all over Azerbaijan.

Left: Miniature from Nizami Ganjavi's "Seven Beauties" (1636). Right: Scene from Nizami's "Khosrov and Shirin" (1636). The Institute is located in the former Alexandrian Russian Muslim Female Boarding School, which was built by Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev between 1898 and 1901. This was the first girl's school in the Muslim East. The building was designed by Polish architect Joseph V. Goslavski (1865-1904), who also designed Baku's City Hall and Taghiyev's private residence, which now serves as the Taghiyev Museum housing the National History Museum collection.

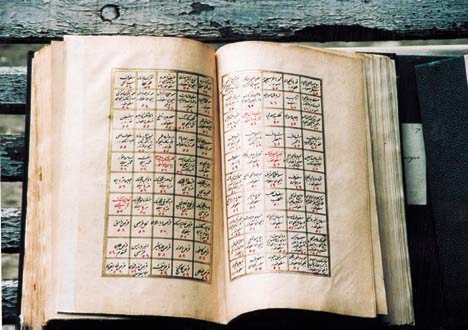

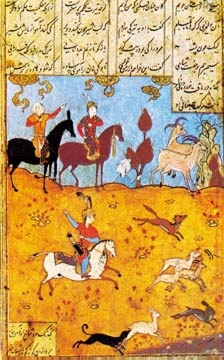

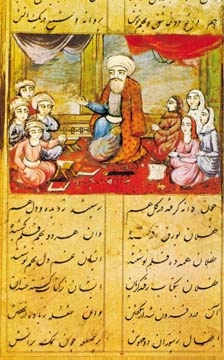

Left: Miniature from Amir Khosrov Dahlavi's "Eight Paradises" (1579). Right: Miniature from Nizami's "Leyli and Majnun" (17th century). In 1918, when Azerbaijan became independent, Taghiyev gave the building to the government of Azerbaijan to be used for ministers' offices. In 1920, after the Red Army invaded Azerbaijan, the Bolsheviks turned the building into the headquarters for the Worker, Peasant and Soldier Deputies. After that, it housed the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Azerbaijan Republic (the governing body of Parliament). Since 1950, the building has housed what is now called the Institute of Manuscripts.  Tribute to Nizami Tribute to NizamiOne of the Institute's greatest treasures is a complete manuscript of "Khamsa", a collection of poems by the 12th-century Azerbaijani writer Nizami Ganjavi, who is often referred to as Nizami. Right: Portrait of Mehmet II (1480) by Sinan bey. The power of aromatherapy recognized centuries ago. The manuscript was copied in 1636 by Dust Muhammed ibn Darvish Muhammed Darakhtichi. This version is unique in that the copyist, after finishing his work with the manuscript, borrowed the oldest "Khamsa" manuscript available and used it to write exhaustive margin notes in his own copy of the manuscript. The text is written in the nastalik Arabic script, a popular style of handwriting that was developed in the 15th century. Even if you can't read the manuscript, it is gorgeous to look at. The title of each poem is decorated with bright colors and graceful golden ornaments. There are 11 miniatures in it belonging to the Isfahan miniature school. The earliest-known miniatures for Nizami's "Khamsa" appear in 15th-century manuscripts. In this period, Nizami's stories were illustrated by artists from the miniature schools of Shiraz and Herat. In the 16th century, Azerbaijani miniatures laid the foundation for the Tabriz miniature school. Important artists included Sultan Mohammad Tabrizi, Agha Mirak, Mirza Ali, Muzaffar Ali and Mir Seyid Ali. The Institute of Manuscripts has many other ancient books that are decorated with miniatures, including: "The Garden of Truth" by Sana'i (painted in 1625), "The Eight Paradises" by Amir Khosrov Dehlavi (1579), "The Seven Beauties" by Nizami Ganjavi (1636), "Divan" by Urfi (17th century), "Divan" by Hafiz Shirazi (1584), "Laili and Majnun" by Maktabi (17th century), "Nushafarin and Govhartaj" (1829), "Divan" by Amir Shahi (1573) and "Divan" by Mohammad Fuzuli (17th century). These colorful miniatures show various scenes of hunting, listening to music, dancing, eating, gardening, fighting and love, as well as natural landscapes, flowers, gardens, nightingales and flowering apricot trees. The most famous miniatures, found in Nizami's "Khamsa", portray the love stories of Leyli and Majnun and Khosrov and Shirin. (For images and more information about the Romeo-and-Juliet-like story of Leyli and Majnun, see "The Man Who Loved Too Much: The Legend of Leyli and Majnun," by Jean-Pierre Guinhut, in AI 6.3, Autumn 1998, page 33.) Scenes include: "Beggar Woman Brings Majnun to Leyli," "The Meeting of Leyli and Majnun," "Leyli Visits Majnun in the Desert," "Khosrov Sees Shirin Bathing" and "Khosrov and Shirin Listen to the Girl's Tales." The miniature named "Hunting" shows how the shah and his huge band of raiders tracked large herds of game (gazelles, deer and wild horses). Medical Manuscripts The most influential medical manuscript housed at the Institute is a 12th-century copy of Avicenna's "Canon of Medical Sciences." Avicenna (Abu Ali Ibn Sina) (980-1037) was born in Bukhara, in what today is Uzbekistan. He did much of his medical observation later on in Persia. The "Canon", written in 1030, is an encyclopedia of medical knowledge considered to be the single most famous book in medical history. The Institute's version of the manuscript was copied in 1143, a little more than 100 years after the text was written. It is one of the oldest Avicenna manuscripts in the world and is considered to be the most reliable. In the 12th century, the "Canon" was translated from Arabic to Latin by Gerard of Cremona (1140-1187) and used as a medical textbook in European universities. The book was held in such reverence that Michelangelo was recorded as saying: "It is better to be mistaken following Avicenna than to be true following others." Ancient Eastern medical texts like the "Canon" emphasize preventative medicine and recommend avoiding the overuse of animal fats. Herbs and aromatherapy were considered to be an important part of staying healthy. Unfortunately, much of the knowledge found in these texts has been lost or forgotten. For instance, out of the 726 medicinal herbs mentioned in Avicenna, only 466 are known to grow in Azerbaijan today. Of these, 252 are not being used for any modern medicinal purpose. Another important Persian medical manuscript found at the Institute is "Souls of Bodies" (Arvh al-Ajsad) by Shamsaddin ibn Kamaladdin Kashani. This medical encyclopedia was copied at the end of the 17th century on high-quality European paper with filigree. In his volume, Kashani gives an exhaustive explanation of all kinds of medicine and diseases, from the simplest to the most complex. Before writing the book, Kashani carefully studied the works of his predecessors, including ancient and medieval physicians like Hippocrates, Galen, Zakaria Razi, Ismayil Gurgani and Ibn Baitar. His encyclopedic work is of great importance because it lists manuscripts that are not registered in any known and published catalogues or reference books in the world manuscript depositories. Rare Texts Law is the subject of a 15th-century text by Mohammad bin Abubakr ash-Shafi. In "Irshad al-Muhtaj ila Sharh al-minhaj," Abubakr provides one of the largest and most popular commentaries to a work on Muslim law known as "Minhaj at-Tlibin." This latter work was written by a famous 13th-century lawyer named Imam Muhiaddin Abi Zakariya Yahya bin Sharaf an-Navai ash-Shafii. The Baku manuscript version of "al-Irshad" is of great interest because it was handwritten by the author himself. His inscription allows us to put an end to inaccuracies in some catalogues and sources concerning the author's name and the title of his work. Another rare work that deserves special attention is "Kitab at-Tanjim", a 15th-century Azerbaijani manuscript on astrology. The author, an Azerbaijani scientist named Hoja ibn Adili Ibrai, provides information about the various signs of the zodiac, the influence of the stars and planets on human destiny and the casting and reading of horoscopes. The manuscript shows that the Azeri language was already very well developed by the 15th century. Even then, it had terms for expressing specific astronomical, astrological, geographical, philosophical and ethical notions. These few ancient texts that I've mentioned barely scratch the surface of what is available at the Institute of Manuscripts. There are also old lithographs, such as "Gudsi Canon" by A. A. Bakikhanov (Tiflis, 1831), "The Tatar ABC Book" by Mirza Kazimbey (Kazan, 1839), "Mother Tongue" by Hasan ibn Mehdi (Tabriz, 1894), "Muntakhabati-Turki" by Mirza Shafi Vazeh (Tabriz, 1855), "Collection of Verses by Famous Caucasian and Azerbaijani Poets" (Leipzig, 1867), "The History of Dagestan" by Mirza Hasan al-Gadari (St. Petersburg, 1894) and "The History of Azerbaijan" by Hasan Bakharli (Baku, 1921). The Institute also has a large collection of newspapers and magazines from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. These publications describe historical events as they happened: the Revolution in Russia, the first declaration of independence in Azerbaijan, the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict, the British army's arrival in Baku, the invasion of Russian troops in Azerbaijan, the Stalinist Repression, the various alphabet transitions and the development of industry and education in Azerbaijan. Istiglaliyyat

Avenue #8 (Independence Avenue) For more information

about Farid Alakbarli's study of ancient medical manuscripts

found at the Institute of Manuscripts, see the article "The Medical Manuscripts of Azerbaijan," by Betty

Blair, AI 5.2, Summer 1997, page 51. Back to Index

AI 8.2 (Summer 2000) |