|

The Shirvanshah

Palace

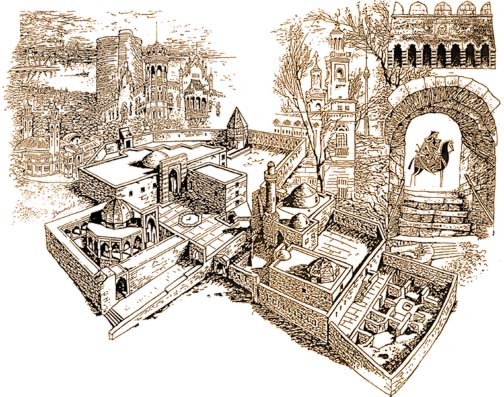

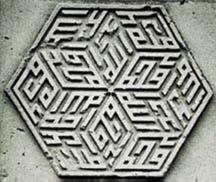

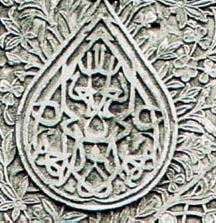

Ornamental designs found on the buildings of the Shirvanshah Palace. Left: A hexagon with six rhombuses inscripted in stylized Arabic with tenets of the Shiite Islamic faith: There is no other god but God, Mohammad is his prophet, Ali is the head of the believers. Right: A hexagon composed of 12 rhombuses with inscription from the Koran. Below: Drop-like medallion from the Royal Tomb with the name of the architect, Mohammad Ali, and the word for architect (me'mar) encrypted to be read in the reverse reflection of a mirror.  An Egyptian historian named as-Suyuti described the father in superlative terms: "He was the most honored among rulers, the most pious, worthy and just. He was the last of the great Muslim rulers. He ruled the Shirvan and Shamakhi kingdoms for 50 years. He died in 1465, when he was about 100 years old, but he had good eyes and excellent health." The buildings that belong to the complex include what may have been living quarters, a mosque, the octagonal-shaped Divankhana (Royal Assembly), a tomb for royal family members, the mausoleum of Seyid Yahya Bakuvi (a famous astronomer of the time) and a bathhouse. All of these buildings except for the living premises and bathhouse are fairly well preserved. The Shirvanshah complex itself is currently under reconstruction. It has 27 rooms on the first floor and 25 on the second. Like so many other old buildings in Baku, the real function of the Shirvanshah complex is still under investigation. Though commonly described as a palace, some experts question this. The complex simply doesn't have the royal grandeur and huge spaces normally associated with a palace; for instance, there are no grand entrances for receiving guests or huge royal bedrooms. Most of the rooms seem more suitable for small offices or monks' living quarters.  This unique building, located on the upper level of the grounds, takes on the shape of an octagonal pavilion. The filigree portal entrance is elaborately worked in limestone. The central inscription with the date of the Assembly's construction and the name of the architect may have been removed after Shah Ismayil Khatai (famous king from Southern Azerbaijan) conquered Baku in 1501. However, there are two very interesting hexagonal medallions on either side of the entrance. Each consists of six rhombuses with very unusual patterns carved in stone. Each elaborate design includes the fundamental tenets of the Shiite faith: "There is no other God but God. Mohammad is his prophet. Ali is the head of the believers." In several rhombuses, the word "Allah" (God) is hewn in reverse so that it can be read in a mirror. It seems looking-glass reflection carvings were quite common in the Oriental world at that time. Left: Entrance to the Turba of the Shirvanshah Palace. Photo: Blair Scholars believe that the Divankhana was a mausoleum meant for, or perhaps even used for, Khalilullah I. Its rotunda resembles those found in the mausoleums of Bayandur and Mama-Khatun in Turkey. Also, the small room that precedes the main octagonal hall is a common feature in mausoleums of Shirvan. The Royal Tomb This building is located in the lower level of the grounds and is known as the Turba (burial vault). An inscription dates the vault to 1435-1436 and says that Khalilullah I built it for his mother Bika khanim and his son Farrukh Yamin. His mother died in 1435 and his son died in 1442, at the age of seven. Ten more tombs were discovered later on; these may have belonged to other members of the Shah's family, including two more sons who died during his own lifetime.

Left: Hewn stone for the reconstruction of the Shirvanshah Palace. Right: The graceful lines in the design of one of the 15th century doors of the Shirvanshah complex. Photo: Left: Blair, Right: Litvin The entrance to the tomb is decorated with stalactite carvings in limestone. One of the most interesting features of this portal is the two drop-shaped medallions on either side of the Koranic inscription. At first, they seem to be only decorative.  Photo: The main Shirvanshah building has been under reconstruction for much of this decade. Photo: Blair The Turba is one of the few areas in the Shirvanshah complex where we actually know the name of the architect who built the structure. In the portal of the burial vault, the name "Me'mar (architect) Ali" is carved into the design, but in reverse, as if reflected in a mirror. Some scholars suggest that if the Shah had discovered that his architect inscribed his own name in a higher position than the Shah's, he would have been severely punished. The mirror effect was introduced so that he could leave his name for posterity. Remnants of History Another important section of the grounds is the mosque. According to complicated inscriptions on its minaret, Khalilullah I ordered its construction in 1441. This minaret is 22 meters in height (approximately 66 feet). Key Gubad Mosque, which is just a few meters outside the complex, was built in the 13th century. It was destroyed in 1918 in a fire; only the bases of its walls and columns remain. Nearby is the 15th-century Mausoleum, which is said to be the burial place of court astronomer Seyid Yahya Bakuvi. Murad's Gate was a later addition to the complex. An inscription on the gate tells that it was built by a Baku citizen named Baba Rajab during the rule of Turkish sultan Murad III in 1586. It apparently served as a gateway to a building, but it is not known what kind of building it was or even if it ever existed. In the 19th century, the complex was used as an arms depot. Walls were added around its perimeter, with narrow slits hewn out of the rock so that weapons could be fired from them. These anachronistic details don't bear much connection to the Shirvanshahs, but they do hint at how the buidings have managed to survive the political vicissitudes brought on by history. Visitors to the Shirvanshah complex can also see some of the carved stones from the friezes that were brought up from the ruined Sabayil fortress that lies submerged underwater off Baku's shore. The stones, which now rest in the courtyard, have carved writing that records the genealogy of the Shirvanshahs. The complex was designated as a historical site in 1920, and reconstruction has continued off and on ever since that time. According to Sevda Dadashova, Director, restoration is currently progressing, though much slower than desired because of a lack of funding. Seyran Valiyev and Fuad Akhundov both contributed to this article. The book "Baku" by Leonid Bretanskiy was also referenced (Iskusstvo (Art) Publishing House: Leningrad, Moscow, 1970). From Azerbaijan International (8.2) Summer 2000. © Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved. Back to Index

AI 8.2 (Summer 2000) |