|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

43-47

In Search of Peace for Nagorno-Karabakh

Interview with

U.S. Ambassador Carey Cavanaugh by Betty Blair

Left: U.S. Ambassador Carey Cavanaugh and

U.S. Ambassador William Taylor meeting with President Heydar

Aliyev. Cavanaugh is in charge of negotiations for Nagorno-Karabakh,

and Taylor administers aid to the former NIS countries. Left: U.S. Ambassador Carey Cavanaugh and

U.S. Ambassador William Taylor meeting with President Heydar

Aliyev. Cavanaugh is in charge of negotiations for Nagorno-Karabakh,

and Taylor administers aid to the former NIS countries.

The

conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh

is now entering its ninth year.

Among the long-range problems that must be resolved in the region,

there is no higher priority. Is there an end in sight to this

conflict that has killed tens of thousands of people and left

nearly one million Azerbaijani civilians homeless?

Though the conflict involves a rather small area in a mostly

mountainous region in the foothills of the Caucasus, the politics

are so complex that it now requires international cooperation

to resolve.

Betty Blair interviewed U.S. Ambassador Carey Cavanaugh to get

his perspective on this process. Cavanaugh is Special Negotiator

for Nagorno-Karabakh and the Newly Independent States (NIS),

representing the United States in its role as one of the three

co-chairs of the Minsk Group of the OSCE (Organization for Security

and Cooperation in Europe).

The Minsk Group is the official international institution commissioned

to seek ways to end the conflict. The Minsk Group, established

on March 24, 1992, consists of 13 of the 55 OSCE member states

from Europe, Central Asia and North America. The co-chairmanship

is led by three nations: the United States, France and Russia.

Other Minsk Group members include Norway, Austria, Belarus, Germany,

Italy, Sweden, Finland, Turkey as well as Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Recently Ambassador Cavanaugh initiated an Outreach Program to

meet with Americans who are concerned about these problems. Of

course, it's quite easy to find Armenians living here in the

United States, but Azerbaijanis from the Republic are few and

far between. Cavanaugh's office at the U.S. State Department

in Washington, D.C. was interested in finding ways to reach out

to the Azerbaijani community as well. That's when they contacted

Azerbaijan International magazine.

This interview took place on November 8, 2000. The discussion

that follows shows the depth of knowledge that Cavanaugh has

about the region, as well as his personal determination and commitment

to make a difference in the lives of the people whose destinies

have been shattered by this catastrophic war.

The question remains: Can peace can be attained? Can relationships

be healed and recreated between neighbors who used to share so

much together? Cavanaugh believes that peace is possible and

tirelessly pursues practical ways to rebuild trust and confidence

in a process that he's convinced "can't happen soon enough."

_______

Ambassador Cavanaugh, in your travels throughout the U.S.

as Special Negotiator for the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, I'm

wondering what concerns the American-Armenian community has about

the peace process in Nagorno-Karabakh? What are they saying?

These past several months, I've been trying to reach out to American

citizens about these issues. I believe it's important for them

to know what we're doing at the State Department on foreign policy

in areas that concern them. In terms of Nagorno-Karabakh, there's

significant interest among the Armenian-American community, the

American academic community and American business. I've spoken

to Armenian-American groups in California, New York and Michigan.

I've met with company representatives who are looking to invest

in the region and trying to find out what's going on there. I've

also addressed university audiences at Stanford [Palo Alto, California]

and Wayne State [Detroit, Michigan]. About 10 days ago, I spoke

at a Harvard [Cambridge, Massachusetts] seminar on the Caspian

region.

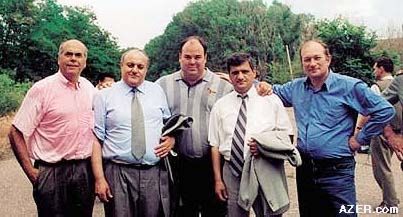

Above: OSCE Minsk Group co-chair

who are responsible for negotiations for Nagorno-Karabakh met

in "No-man's land" on the border between Azerbaijan

and Armenia with the respective governors of the regions. Left:

Russian co-chair Nikolai Gribkov, Armenian governor Armen Ghularian,

U.S. co-chair Carey Cavanaugh, Azerbaijani governor Avaz Orujov,

and French co-chair Jean-Jacques Gaillarde. Summer 2000.

What aspects of the peace process are they concerned about?

They want to know: How can it be moved forward? How can it be

resolved? There's a concern that it's very difficult for the

Armenian economy to normalize until there's a peace settlement.

So there's a lot of support for a resolution.

The other thing that you pick up from a foreign policy perspective

is their concern about Armenia's lack of relations and problematic

history with Turkey: How can that be dealt with? How can it be

advanced? In the past few months, there have been some major

issues on the question of the "Genocide Resolution"

that was passed by the International Relations Committee of the

U.S. House of Representatives.

In regard to Karabakh, Armenians understand the realities of

what President Aliyev [Azerbaijan] and President Kocharian [Armenia]

have been saying over the past year. These two leaders have had

several sessions of direct dialogue, which has altered the dynamics

of the peace process. They've made very clear their desire to

find a solution. I believe that they're committed to finding

a resolution to this conflict. And they've been telling their

people that to achieve a peaceful resolution, there have to be

serious compromises. This has been a common refrain for them.

I've heard those ideas expressed on the Azerbaijani side by

President Aliyev. But President Kocharian is saying the same

thing to his people?

They're both saying exactly the same thing. In the Armenian community

in the U.S., I've found a very solid understanding of that. They

realize that it's a difficult situation on the ground. If you

want to bring this kind of conflict to an end, then of course,

there has to be compromise. They're not aware of the exact details

that the presidents have been discussing. We, ourselves, cannot

disclose that either because of the delicacy of the negotiations.

But the Armenian-American Diaspora is supportive of the idea

that serious compromise must be made to find peace.

Let's talk about your work as Special Negotiator. First of

all, how long have you been at your assignment?

I've been the Special Negotiator for a little over a year now,

but I also worked on these problems in 1994-1996. After I finished

graduate school [University of Notre Dame], I taught International

Affairs in Ohio and joined the U.S. Foreign Service in 1984.

I started working on Soviet affairs in 1988 and was assigned

to Moscow in 1989-1991. Before the breakup of the Soviet Union,

I also traveled to the Caucasus. After its collapse, I was selected

to open up the U.S. Embassy in Georgia in April 1992 because

I had worked closely with Shevardnadze when he was Foreign Minister

in Moscow.

So you opened up the Georgia office?

While I was there, we bought the Embassy building, hired the

staff and set everything up. We also brought in several planeloads

of economic assistance. I did it all rather quickly because I

was en route to another assignment.

For at least 10 years I've been working, off and on, with issues

related to this region-peacekeeping and trouble-shooting, sometimes

in work related to Georgia; sometimes, Nagorno-Karabakh; sometimes,

Greek and Turkish problems and Cyprus. I was also in Switzerland

helping to resolve the problem of "Nazi Gold" and Holocaust

era assets. When that was wrapped up, I came back to work on

the Nagorno-Karabakh problem.

Do you speak Russian?

Yes. That makes things a lot easier. It gives you the ability

to have personal conversations without intermediaries, which

is important both with leaders and ordinary citizens.

Without all the acrobatics of translations that you have to

go through otherwise.

It also gives you the chance to establish a deeper personal relationship

with decision-makers, which I think is important in this kind

of work. Leaders need to be able to communicate well with you

and have confidence in you. This has certainly been the case

with President Aliyev.

What about the other two co-chairs [of the Minsk Group]? Of

course, the Russian representative [Nikolai Gribkov] speaks Russian.

The French co-chair [Jean-Jacques Gaillarde] does, too. In fact,

all three co-chairs speak Russian and all three speak English.

I'm probably the weakest when it comes to speaking French. I

speak some. Having worked before in Rome, however, I must admit

my French has a bit of an Italian accent to it.

The other two OSCE co-chairs started about the same time that

I did. This is normally a two- to three-year assignment, so there's

been periodic rotation.

I was wondering about the background of the U.S. situation.

How many ambassadors have represented the United States up until

now? As I understand, Ambassador Maresca started this back in

1992. [See Interview with Maresca in AI 4.1, Spring 1996.]

Yes, Jack Maresca was the first person involved with the Minsk

Group. At the time, he was also working on Cyprus and other OSCE

issues. I think the first full-time person was Jim Collins, who

did it for a short while before replacing Strobe Talbott as Ambassador-at-Large

for the NIS. Collins is now our Ambassador in Moscow. Then came

Joe Presel, Lynn Pascoe, Don Keyser and then me.

That's quite a few of you.

Well, it's a big conflict that has been going on for quite a

while.

Isn't it difficult when you have five to six different people

dealing with the same issue over just an eight-year period?

Not really because when Joe Presel was working on this, I was

working on it as well. So this kind of arrangement has been an

asset.

So there's overlap there?

Yes. For example, when I worked on these issues in 1994, in addition

to President Aliyev, I dealt with Arkady Ghukasyan, then "Foreign

Minister" of Nagorno-Karabakh, and now its leader.

I also dealt with Robert Kocharian, then leader at Stepanakert

[Armenian name for the capital city of Nagorno-Karabakh, which

Azerbaijanis refer to as "Khankandi"] and Vartan Oskanian,

currently Foreign Minister of Armenia. So I have long-term, established

relationships with all these players.

Is it a full-time job?

Very much so. It's a job that has me and the people in my office

on the road probably 50-60 percent of the time.

How is that? What does your job entail?

I should add that I'm responsible for trying to help resolve,

not only Nagorno-Karabakh, but also conflicts in Georgia. There

are two there: one in Abkhazia and the other in South Ossetia.

I also am involved with helping advance a settlement between

Moldova and Transneister, another breakaway region.

Actually, that's a major difference between myself and the other

co-chairs of the Minsk Group. They only deal with Karabakh. If

you ignore the heavy workload that this sort of arrangement requires,

I believe there are strong advantages to having one diplomat

handle all these conflicts together, instead of in isolation

- one by one. When they're handled together, it provides a broader

perspective. You also end up dealing with a wider variety of

players in Moscow. Effective engagement with Moscow is a key

factor in finding a solution to Karabakh.

In the United States, the broader portfolio also gives me greater

access to our own leadership, including Secretary of State Madeleine

Albright or Vice President Gore or even President Clinton, depending

on what develops in relation to the different conflicts.

I understand that Madeline Albright has been personally involved

with the Karabakh issue over the years. I know that she's met

with President Aliyev and President Kocharian on several occasions.

What do you feel her contribution has been in all of this?

She has made a very significant contribution. The NATO Summit

that took place in Washington in April 1999 on the occasion of

NATO's 50th Anniversary led to the convening of all the NATO

countries and all Partner for Peace Countries. Aliyev and Kocharian

were both there. What she did was basically put them in a room

and say, "Talk to each other," and then she left them

alone. That marked the beginning of their substantive dialogue

together, which has lasted now for more than a year.

So that was the first time that they had spoken together directly?

They had met together earlier in Moscow, but I don't think they

had had serious discussions. I think that when Albright brought

them together, that was the first time that they ended up sitting

down and seriously thinking about what they could do to come

up with a solution. Since then, she has met with them several

times and worked directly with them in trying to move the peace

process forward. And, I might add, so has President Clinton.

In what ways?

He has been particularly engaged since the two presidents began

their direct dialogue. He has had meetings with both of them.

He met them separately at Istanbul at the OSCE Summit, November

1999. He saw them again in Davos, Switzerland, January 2000,

although that was a brief encounter. Secretary Albright had longer

meetings with them there, but Clinton saw them as well.

More recently, he met them when they visited the United States.

Aliyev visited Washington in February 2000 and Kocharian followed

in June. Clinton focused on the peace process with both leaders.

More recently, both were in New York with Clinton in September

for the UN Millennium Summit. These were brief encounters. It

was also the last time that the two presidents met together.

[Since this interview, Aliyev and Kocharian met in Minsk (Belarus)

on December 1, 2000 for the CIS Summit (Commonwealth of Independent

States). They are also expected to meet again in Strasbourg,

France, in January 2001 when the two countries are admitted to

the Council of Europe].

When Aliyev and Kocharian meet together, are the OSCE co-chairs

present?

No. This is a direct dialogue between the two, which I believe

is the best way to find the basic outline for the solution. More

than anyone else, these leaders know what is acceptable and what

is not. They know what their respective populations are willing

to do and what it takes to bring about a settlement.

The Minsk Group co-chairs travel to the region frequently as

well as meet the presidents at various locations around the world.

Our work with them individually can help bridge differences as

they work on the peace process together.

I know that the negotiations are secret right now. Both leaders

are not saying what they're working on. But last winter (1999),

Aliyev told the Azerbaijanis: "I want people to know that

they shouldn't worry about this. It won't be implemented without

Parliament being involved or even a referendum."

That's true. Such a strategy is crucial. The peace agreement

must be acceptable to all parties. It has to involve serious

compromise. There's a desire that it be a peace that can take

effect quickly (if such can be achieved), and that it be very

straightforward and easy for people to understand.

The other aspect that has been clear from the beginning is that

it cannot simply be a deal that the two presidents work out on

paper. It has to go back to the people. There are a variety of

ways that this can be done. One could be parliamentary involvement

or a referendum. The leaders have not finalized exactly how this

will be done, but I know they understand such a process would

give any final agreement the durability necessary to withstand

the passage of leaders.

Would both sides follow the same process in their respective

countries?

It depends on how the agreement is reached and also upon the

constitutional provisions in each country. For instance, if both

held referendums, which is possible, there might be slight differences

in how one country's constitution is set up to carry out a referendum.

The key is to have an agreement that the people themselves support.

Then it will take on a life of its own.

This group of co-chairs [U.S., Russia and France] has been

the negotiating body since 1998, right?

Yes.

As I recall, the chairmanship of the Minsk Group used to change

every year.

You're right. At one point, it was led by the Finns, then the

Swedes, then Russians joined as co-chairs. But this current arrangement

of a triple co-chairmanship seems to be the most effective.

What else does your job entail?

We have frequent contact with other leaders in the region both

directly and also with my counterpart co-chairs. Also, there's

quite a bit of engagement in Washington to develop policy and

work with the U.S. Congress to make sure that Senators and Members

are aware of our efforts and activities. There's also the Outreach

Program that I described earlier, which involves meeting with

Americans who are concerned about these problems. Finally, we

consult with other European countries and other international

institutions.

I should add that we often make tours in the disputed regions.

On one of our last trips, the Minsk Group co-chairs visited the

Azerbaijani city of Aghdam [now under Armenian occupation]. We

wanted to see the extent of damage that the war had brought and

begin to assess what would be needed to repair the city.

On that same trip, we went to Shusha and Lachin [other occupied

Azerbaijani towns. Shusha is in Nagorno-Karabakh. Lachin, close

to the Armenian border, is a small town through which Armenians

link to Nagorno-Karabakh].

We also visited two major refugee camps. We met hundreds of refugees

at Barda [in central Azerbaijan] where I made a presentation

and spoke to many of them individually so that they would know

what we were trying to do - that our goal is to find a genuine

solution so that they can get back to normal life.

We also went to the Bilasuvar camp, where the refugees have actually

been living in mud huts for the past seven years [as of December

1999]. Some of the children have lived their entire lives there

and are now in first grade. They've seen nothing else of the

world. When you visit camps like this, you realize first-hand

how difficult their life is.

Visiting the refugees helps us focus directly on the urgency

of a peace settlement so that it doesn't become an abstract political

concept. Our ideas are based on concrete human reality. A peace

settlement means rebuilding cities, resettling people and reestablishing

normality in their lives.

On our last visit in the region on July 4, we were concerned

that the cease-fire be maintained. Although the official cease-fire

has been in effect since 1994, still there are shootings that

end in tragic deaths along the line of contact every year.

During this past year alone, about 100 people have been killed

in these border disputes. So on this trip, we traveled to Kazakh,

a town in the northwest corner of Azerbaijan. Then we crossed

over into Armenia. We chose that region because quite a number

of people have been killed there. [The Minsk co-chairs did this

again at a different border crossing in December 2000 after this

interview took place.]

For example, a young Azerbaijani girl had recently been shot.

She was inside her home when a bullet came through the window

and killed her. When we talked to the local governor, he pleaded,

"How can we deal with this? What do I say to people when

these tragic things happen?"

People have also been shot on the Armenian side. Before we crossed

the border, we conferred with both militaries to facilitate our

trip. They had to clear mines. Then they laid down a telephone

line across the border so that we could communicate with the

other side to tell them that we were coming so that no one would

get confused and start shooting.

But we didn't make this trip alone. We invited the Azerbaijani

governor of Kazakh and the local military commander to come along

and meet their counterparts on the Armenian side. We arrived

in that "no-man's land" and stood around together for

the purpose of carrying on a concrete discussion: "What

can be done to reduce the civilian casualties?" It was a

wonderful experience. Both sides talked for hours [in Russian].

Very animated. Very heartfelt and emotional. Violations of the

cease-fire agreement is not an abstract issue for them; they

have to deal with it everyday and explain why these things are

happening.

Both Azerbaijanis and Armenians were concerned about the lack

of communication between the two sides, realizing that some of

these flare-ups were accidental and, therefore, could be prevented.

For example, a soldier might accidentally set off his gun, perhaps

just in the process of cleaning it or not handling it properly.

Soldiers on the other side hear those shots and retaliate. Then

the shooting continues back and forth until someone gets killed.

Such incidents have been triggered by something as simple as

the accidental firing of a round, and there's been no mechanism

in place to tell the other side, "A guy dropped his gun

and it went off. Don't worry!"

So we arranged for the telephone line that was set up for our

visit to be kept in place. If that kind of incident occurs again,

then one side can immediately telephone the other side and say:

"It's nothing. It was an accident."

Sometimes even goats, sheep and cattle wander into the cease-fire

zone and step on land mines. An explosion goes off. Everyone

gets frightened, wondering if someone is trying to sneak across

the border. But again, such fears could be allayed simply via

the telephone. So we left that telephone line, and now we're

in the process of getting radios. Last week while there in Azerbaijan

and Armenia, we spoke about this with the two Defense Ministers.

OSCE will provide radio units for both sides all up and down

the border so that the troops will be able to communicate with

each other.

The other thing that we did on this last trip was to look at

some of the economic development projects that need to be done.

We went to the Red Bridge - the bridge connecting Georgia with

Azerbaijan. We wanted to see how to enhance some of these transportation

links and roads, because these same road links used to go from

Kazakh [Azerbaijan] to Ijevan [Armenia].

Also when we were in Kazakh, farmers pointed out that they used

to sell their produce in Armenia. In fact, there used to be an

active railway line between the two regions. While in Armenia,

we tried to figure out what would be needed to put the railroad

back in place, as sections of the track have been removed so

that it's non-functional today.

But if there were a peace settlement, it's clear that all these

countries will need to work together for the economic prosperity

of the entire region. We're looking at what could be done to

reestablish the economic infrastructure once a peace settlement

is put in place.

The logical transportation link from Azerbaijan to the West also

goes through Georgia and Armenia. The logical links for Armenian

trade include Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey.

Also on that trip, we went to Stepanakert to see the pipeline

that used to bring natural gas from Baku to Karabakh en route

to Nakhchivan [Azerbaijan].

What about the problem of water? When I was in Kazakh in 1994-95,

there were a lot of vineyards that had totally withered and dried

up because the Armenians had stopped the flow of water from the

dam on their side of the border.

Water problems is another area that we've been looking at. Cooperation

on water projects would benefit both sides. Some of these projects

could be put into place even before a peace settlement is completed.

But so many of them depend upon a final resolution. You can do

a little but, absent a solution, it's hard to do the things that

are seriously needed. I think that's what the two Presidents

are realizing. We have to find ways to break this impasse in

order to build the foundation for the future in this region.

The unresolved conflict in the region today places restraints

on everything else that the people and the leadership would like

to undertake. It's clear that Armenia wants to develop its economy.

It's clear that President Aliyev wants to develop a full economy

- not one that relies only on oil and gas - but one that has

a whole variety of sectors, which guarantees that everybody will

be included in the economic development. But the way to secure

economic development requires a peaceful resolution of the conflict

and the re-establishment of economic infrastructure as well as

the return of nearly a million refugees back to their villages

and towns. So every path leading to the future takes you back

to the absolute necessity of finding a peaceful solution.

Can you tell me a bit about what you saw when you went to

Aghdam? That city used to have a population of about 90,000,

I believe.

It was a significant city, and a significant amount of destruction

has occurred there. That trip led to our organizing a conference

in Geneva of nearly 20 agencies last May because we realized

the scope of what is needed for reconstruction. It's enormous.

We brought together UN agencies, independent agencies, the International

Red Cross, groups like the World Bank and European Union. We're

now starting to plan how we would handle implementation of the

peace - specifically, how we would handle economic reconstruction

of the region and resettlement of the refugees.

You don't displace a million people without stupendous repercussions.

It's going to take an enormous reconstruction effort. I must

say that we were very pleased to see the positive response from

the international community. They are willing to help if a solution

can be found.

But right now, it seems as if humanitarian aid is dwindling

for Azerbaijani refugees.

There are always competing demands on the international community

when it comes to aid for refugees, especially given what is going

on these days in the Sudan and the Far East. But if a peace settlement

can be found, many agencies will do what they can to be involved

with its implementation.

But tell me more about your trip. What was Shusha like?

Shusha is in better shape than Aghdam, obviously. There's much

more of the city left there. It's not fully inhabited. The mosque

is being repaired and renovated now.

And Lachin. There's a road now that the Armenia Diaspora has

built that runs through it connecting Karabakh to Armenia.

The road has been refurbished. It's a very small town.

Every so often, I hear about discussions about land swaps. Can

you talk about that?

As I've said, we've been very straightforward with the presidents,

promising not to talk about any details of what they discuss.

That means we can neither confirm nor deny anything. I think

it's important that both sides are willing to compromise and

find a bolder solution than the kind that the Minsk Group had

offered in the past.

A solution that is encompassing enough so that 25 years from

now, we aren't faced with it all over again.

I think they're committed to that. No one wants a settlement

that won't work. The idea of getting a peace deal that would

only last a year or so makes no sense at this point. You want

something that is definitive enough that people understand it

and support it. Also, you need such an agreement to garner support

from the international community and attract money to get things

fixed. No one wants to invest in economic reconstruction and

then have it destroyed in renewed conflict.

Can you tell me a little bit about the Lisbon Summit [OSCE

Conference in 1996]? The principles that were set out and agreed

upon by the OSCE at that time, are they still in effect?

Certainly. The main point became "respect for territorial

integrity". Territorial integrity is always part of the

discussions going on, not simply as it relates to Nagorno-Karabakh

but also to the situations in Moldova and Georgia. I think what

is important though is not so much to focus on things like-saying,

"We insist on territorial integrity," while someone

else says, "No, we demand self-determination." Rather,

peace will come by focusing on the practical aspects of what

would be a realistic solution.

There are ways to find solutions that do not pose problems for

either "territorial integrity" or "self-determination".

It may call for some creativity, but I think there are ways to

bridge these gaps.

Let me ask you about Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act.

The fact that U.S. funds are going directly to the Armenian government

but not the Azerbaijani government because of Congressional restraints,

do you believe this "ties your hands" in terms of being

perceived as a fair and honest broker in these negotiations?

I think Azerbaijanis understand.

What makes you feel that way?

Mainly the interaction that I have with President Aliyev.

But the people in the street don't necessarily have the perception

that the U.S. is fair.

Yes, some people on the street might not understand. It's hard

to convey that we are fair because it raises for them the basic

question: "Why is there open assistance on the one side

and these restrictions on the other?" But in our work in

facilitating peace, I think they understand that we really are

an honest broker.

So how do you fit your busy schedule and all this work into

your family life?

The pace of work and the amount of travel required in this job

create a lot of pressure and take a real toll on normal family

life. My boys, for example, are six and 12; sometimes it's quite

upsetting for them. Every time they turn around, they see me

flying away. I spent the Fourth of July in the Caucasus. And

then Halloween. I came home for Thanksgiving and virtually the

next day I flew off to Europe to deal with these problems. My

wife has to carry on life almost like a single mother. In the

end, I think they all understand the importance of this work

but, I'll admit, it's hard.

If you were trying to guess when peace might come between

Armenia and Azerbaijan, what would you predict?

I would say, "Not soon enough!" Having seen the suffering

and needs on both sides, I think the sooner it comes, the better,

because it is desperately needed. It's impossible to say when

the leaders will find a package that works. It depends so much

on their ability, their political support and courage. It's not

unfair to say that some of these steps toward peace that these

political leaders must take may be the most difficult decisions

of their careers, requiring enormous courage.

This is a very unique moment in history because of the dissolution

of the Soviet Union. Do you feel like you're a different person

because of your involvement in these Nagorno-Karabakh negotiations

these past few years? Are you, for example, a different person

today than you were 10 years ago?

Yes, I think in many ways, I am. I've seen a lot of suffering,

but also I see the progress that can be made. This is a very

unique job. It's challenging. Sometimes the task is daunting,

but it comes with enormous opportunities for success in creating

peace.

It's not like being involved in business and going out to sell

something. It's not like any other job. Success here affects

millions of people. A solution brings more than a million people

out of camps and back to their homes. So it's rewarding, but

it also carries an enormous responsibility. It gives you some

sense of the responsibility that the leaders of these countries

carry on their shoulders. Although I've visited these refugee

camps and seen these people and talked with them, the respective

leaders have to deal with this all the time. In this position,

you end up engaging in a level of policy that can have an enormous

impact.

Someone pointed out to me that the work of a peace negotiator

is, in essence, God's work. In the Bible in the book of Matthew,

it says, "Blessed are the peacemakers." It would be

hard to find a nobler profession than this. The stakes are so

high. The rewards are so valuable. How could such work not change

you?

An OSCE office was established in Baku on November 16, 1999;

and in Armenia on July 22, 1999.

For more information about the mission and activities of the

OSCE, visit Web site: : www.osce.org.

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

Karabakh

Conflict

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|