|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

50-55

Hands Tied

Denying

Aid to Baku - Section 907

The U.S. Embassy to

Azerbaijan

Interview

with Ambassador Stanley Escudero by Betty Blair

In 1991, the event that

the West had been waiting decades for finally happened - the

Soviet Union collapsed. Relieved that the Cold War was over,

the U.S. vowed to help the former Soviet republics make the transition

from centrally controlled economies to free-market systems supported

by democratic governments. And for the most part, the U.S. made

good on that promise, having set aside more than $8.3 billion

between 1992 and 2001 to help the Newly Independent States (NIS). In 1991, the event that

the West had been waiting decades for finally happened - the

Soviet Union collapsed. Relieved that the Cold War was over,

the U.S. vowed to help the former Soviet republics make the transition

from centrally controlled economies to free-market systems supported

by democratic governments. And for the most part, the U.S. made

good on that promise, having set aside more than $8.3 billion

between 1992 and 2001 to help the Newly Independent States (NIS).

However, in the case of Azerbaijan, interference by Armenians

living in the U.S. prevented the Republic from receiving support.

The U.S. Congress, bowing to special interests, has blocked direct

aid to Azerbaijan's government via Section 907 of the Freedom

Support Act.

Despite carve-outs that, since 1998, have allowed direct assistance

to Azerbaijan for democratization and humanitarian purposes,

the U.S. has allocated a relatively meager amount of aid to Azerbaijan,

as compared to the other Caucasus Republics - Armenia and Georgia.

Most of the aid that Azerbaijan does receive is administered

through U.S. non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Here Stanley Escudero, the U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan (1997

to 2000), speaks with Editor Betty Blair about the impact that

Section 907 has had on U.S. efforts to assist Azerbaijan. Escudero

elaborates on how restrictive this piece of legislation has been,

how it damages U.S. relations with Azerbaijan, and what it means

not to be able to fully assist the Azerbaijani government at

this crucial moment in history.

Above: America's hands are

tied because of U.S. Congressional legislature (Section 907 of

the Freedom Support Act) when it comes to directly helping the

Azerbaijani government find work out solutions to its major environmental

problems. Above: Factory in Sumgayit, an industrial hub of Baku.

This interview took place in the U.S. Embassy in Baku on September

19, 2000, just a few days before Escudero's assignment ended

and he retired from diplomatic service. He and his wife, Jaye,

now reside in Florida. In October, Ross Wilson assumed his duties

as the new U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan.

______

Let's start with the good news first and talk about the positive

ways in which the U.S. is assisting Azerbaijan in its development.

Considering the relatively small amount of aid that the U.S.

has allocated to Azerbaijan, which projects do you think will

make the greatest impact on the country-long-term?

Because I hope and believe that the refugees won't remain refugees

forever, I attach great importance to income-generation projects

and business development projects that assist refugees and other

Azerbaijanis in creating new wealth and in making a personal

contribution to the development of free-market enterprise in

Azerbaijan.

But beyond that, I'm convinced that the most important thing

that we do in Azerbaijan has to do with our student exchange

programs. The largest of these is the FLEX Program (Future Leaders

Exchange) which used to be called the Bradley Program. It was

established in 1992 right after the Soviet Union collapsed [1991],

when we opened all of the Embassies in the Newly Independent

States (NIS).

Above: Dead seal washed up

on beach at Dashlar Island because of oil pollution.

In Azerbaijan, the first exchange students left for the U.S.

in the fall of 1993, didn't they?

That's

correct. We've now sent in the neighborhood of 600-700 students

from Azerbaijan to the United States. These past several years,

we've been able to increase the number of FLEX students that

we've been sending to America. Sometimes, dramatically so. Competitions

administered by ACTR-ACCELS are held in each NIS country, where

students are chosen according to their ability in English. The

students go to live with American families throughout our country

and attend high schools for one year.

Then they return to Azerbaijan to pursue university studies here.

But they return with an extraordinarily different outlook and

an understanding of America that very few Azerbaijanis have because

they've spent a lot of time in intimate American settings. Their

young minds are like sponges that absorb everything they see

and experience. But not only do they bring back a greater realization

of what America is all about, they return with an awareness that

there are different ways of doing things.

They become sensitive to what makes the West more effective and

more efficient in the world today.

We hope this instills a desire to see their own country improve

and adopt some of these methods and systems. Sometimes this makes

for problems. Their families don't always understand their new

way of thinking. And, of course, as young people, they aren't

usually able to immediately replicate the experiences they've

had in the West, so there is often a period of readjustment for

them, which can be frustrating.

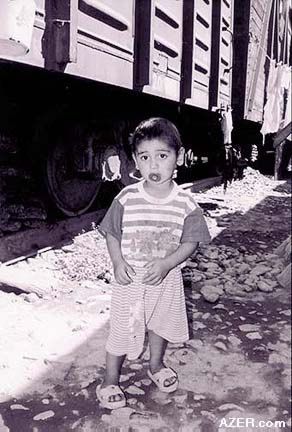

Left: Despite U.S. law prohibiting direct

aid to the Azerbaijani government, the Clinton Administration

managed to create exceptions so that humanitarian aid could be

directed to refugee projects. This young refugee girl, leans

against the ladder leading up to the railway box car where she

has spent all her life growing up. There are hundreds of young

people like her. Saatli. Photo: UNHCR, Vugar Abdusalimov. Left: Despite U.S. law prohibiting direct

aid to the Azerbaijani government, the Clinton Administration

managed to create exceptions so that humanitarian aid could be

directed to refugee projects. This young refugee girl, leans

against the ladder leading up to the railway box car where she

has spent all her life growing up. There are hundreds of young

people like her. Saatli. Photo: UNHCR, Vugar Abdusalimov.

In addition to the FLEX program, we have university and graduate-level

study grants such as the Muskie Program. One of these, the Harvard

MBA Program, was inaugurated just this past year.

As Azerbaijan develops and prospers, it will inevitably have

to mesh with the international community. These young people

- graduates of these programs - will be on the cutting edge of

that process. We think that, over time, these young people will

be the "movers and shakers". They will become the technocrats

who help with the "nuts and bolts of change".

It's not just the individual student who benefits directly

from these programs. The entire family benefits - parents, brothers,

sisters and relatives.

That's certainly true. In fact, one of the phenomena that we've

seen repeated time after time is that brothers and sisters of

graduates apply for these programs as well, and I should add,

successfully so.

But now let's focus on some of the things you can't do in

Azerbaijan because of the restrictions on aid imposed by the

U.S. Congress. Of course, one could argue that no country that

comes to rely heavily on foreign aid will develop much on its

own. Each country must find ways to develop independently. Take

a look at Armenia, a country whose population is barely half

that of Azerbaijan's, but which has received perhaps five times

the amount of U.S. government aid. Yet Azerbaijan's economy is

far more developed than Armenia's. What are some of the ways

that 907 has hampered your efforts at the U.S. Embassy in Baku?

There are many ways. In fact, 907 has essentially retarded the

development of the cooperative relationship that ought to exist

between the United States and the government of Azerbaijan. In

other NIS countries, we have a very wide range of programs directly

with the governments. We assist them in the creation of, the

reform of, or the development of a wide range of institutions

and practices that will better enable them to prepare themselves

for participation in a free-market world. But in Azerbaijan,

we work under very heavy restrictions.

For example, Section 907 has prevented us from helping Azerbaijan

develop a coherent and effective tax collection system. Furthermore,

it has, until quite recently, prevented us from getting involved

to help change Azerbaijan's judicial system or to reform a variety

of laws that would facilitate democratic practice. It continues

to prevent us from helping Azerbaijan change its commercial code.

Section 907 prohibits the U.S. from providing direct aid to Azerbaijan's

government, even to support educational endeavors such as reprinting

text books. As the law stands, the U.S. could not even provide

funding or expertise to help rewrite and republish world history

texts from a non-Soviet point of view. Azerbaijan is the only

Republic of the 12 former Soviet republics that has been denied

direct aid, as a provision to the Freedom Support Act passed

in 1992. The exception was brought on by Armenian activists who

fund the election campaigns of U.S. members of Congress.

Govermental officals both in Azerbaijan and the United States

who understand the effect of these unfair laws insist that such

legislation is detrimental to development in the entire region

and even has long-term negative effects on neighboring Armenia.

Above: Baku State University

as a government institution cannot receive U.S aid, nor can elementary

school kids who attend public schools (below).

Meaning what?

Meaning

the laws that govern commercial activities in Azerbaijan. It

prevents us from assisting Azerbaijan in developing the more

transparent, investor-friendly climate that is necessary for

Azerbaijan to attract foreign investment, especially in the non-energy

sector. The development of the non-energy sector is absolutely

critical to the success of this country because it will be the

non-energy sector and the intelligent use of oil revenues that

will prevent Azerbaijan over time from experiencing the devastating

problems that afflicted other petro-states of the 1970s.

Since 907 has been interpreted quite strictly, we have been unable

to provide Azerbaijan assistance in the control of narcotics

traffic. That remains the case, even though the authorizing language

that creates counter-narcotics assistance programs contains what

is called a "not-withstanding clause", meaning that

this kind of assistance may be provided to countries "not-withstanding

any other piece of legislation". One would think that such

clauses would enable an override of the 907. But the law has

been interpreted otherwise. I think that interpretation may change

soon.

There are other American assistance programs whose enabling legislation

includes "not-withstanding clauses" - the Peace Corps,

for example. Nevertheless, there is no Peace Corps in Azerbaijan.

I hope that, too, will change soon, and that the Peace Corps

will come to Azerbaijan. The Peace Corps has a proud global history,

and there is an opportunity in Azerbaijan for the Corps to make

important contributions to national development, especially in

areas such as English-language teaching and small-business development.

But with respect to our direct relationship with the government

of Azerbaijan, the very fact that 907 even exists is, for them,

an extraordinary and confusing humiliation. Azerbaijan is the

nation in this region whose interests most closely parallel those

of the United States. It is a nation that desires to be close

to America.

When you speak about the "region", how wide is your

reach?

Well, I'm referring to the Caspian basin and, of course, to the

South Caucasus. Azerbaijanis find it very difficult to understand

how the United States, which is generally regarded as a fair

and just country, could pass such a piece of legislation. Furthermore,

they find it even more difficult to understand how the United

States could maintain it year after year.

So how do you explain it to them?

Well, I explain it as a function of domestic American politics.

Do you see any possibility that it will change?

When there is a settlement in Nagorno-Karabakh, of course, it

will change. It's also conceivable that there could be some more

"carve-outs" - some other exemptions created. But I

don't anticipate that the Congress will repeal Section 907, no.

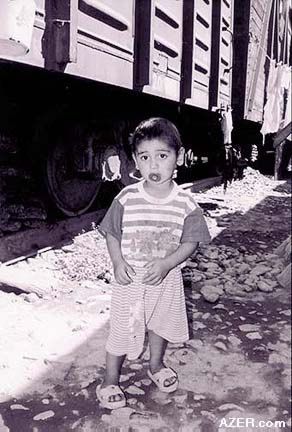

Left: Life in a railway box car is all this

refugee child has ever known. Of all the temporary shelters that

refugees have found to live in, these are considered among the

least desirable. They're too hot in summer and too cold in winter,

with no windows to provide light or ventilation. Saatli. Photo:

UNHCR, Vugar Abdusalimov. Left: Life in a railway box car is all this

refugee child has ever known. Of all the temporary shelters that

refugees have found to live in, these are considered among the

least desirable. They're too hot in summer and too cold in winter,

with no windows to provide light or ventilation. Saatli. Photo:

UNHCR, Vugar Abdusalimov.

Simply because some Congressional members are being funded by

Armenians?

There is no countervailing Azerbaijani lobby. Political realities

in the United States are such that the Congress will respond

to domestic constituencies, especially wealthy, well-organized

ones.

But that's corruption, isn't it?

Some people would call it that. Others describe financial contributions

as a form of free speech and insist that the current level of

influence of special interest groups in the United States is

nothing more than the American political system at work.

Azerbaijanis often say that it's not the money so much as

the lack of integrity that bothers them most. They say: "We

really depended on the United States to be just and true and

honest. We were the victims of this conflict and now they're

punishing us. The aggressors are the ones being rewarded."

Well, again, I can certainly understand why they would feel that

way.

There's also another aspect of U.S. aid that I find very problematic.

On the one hand, the U.S. recognizes that Karabakh is still part

of Azerbaijan, as does the rest of the international community,

with the exception of Armenia. On the other hand, it denies direct

aid to the Azerbaijani government while giving aid to Karabakh,

which is now populated only by Armenians, since all the Azerbaijanis

were forced to flee their homes and villages. It seems like such

a contradiction and so unfair.

The Congress

earmarked $20 million to be spent in Nagorno-Karabakh over a

three-year period. That's an extraordinary amount of money if

you consider that there are only 100,000 or so people in all

of Nagorno-Karabakh. [The Azerbaijani government estimates that

there are approximately only 40,000 civilians, all of them Armenian,

living in Nagorno-Karabakh]. But again, this is a function of

domestic American politics.

My primary concern with 907 is that it is an attempt to impose

unilateral sanctions on Azerbaijan-a strategy that is almost

always a mistake in foreign policy. Moreover, in this particular

situation, the legislation does not reflect the conditions on

the ground. It simply does not reflect the history of the Nagorno-Karabakh

issue. Instead, it shows the influence of the Armenian lobby

in the United States and the influence of campaign financing

on decisions made by the Congress. This is a particular problem

in our country right now, and it is only one example out of many.

Have you addressed Congress about these things? The State

Department seems to know the issues.

The State Department would gladly repeal this legislation if

it had the authority to do so. And no, I have not addressed the

Congress directly on this issue. Congress has not requested my

opinion.

Can you elaborate a bit more on some of the other activities

that you haven't been able to carry out because of 907? Like,

for example, English books? Has it been difficult to bring textbooks

here?

Well, if we

wanted to support a program that would assist Azerbaijan in the

reconstruction of its educational system, or in the provision

of modernized textbooks that deal with, let's say, world history

from a non-Soviet point of view, we would not be able to do it

without a specific exemption from 907.

Such a program would require offering them to the Azerbaijani

school system, which, of course, is part of the government of

Azerbaijan. Therefore, we couldn't do that. It wouldn't matter

if the books were in the English language or in Azeri. We are

able to obtain waivers for certain programs, but these waivers

must be requested and justified on a case-by-case basis.

For example, there are the partnership programs between Azerbaijani

schools and American schools, funded by Public Diplomacy and

other similar programs. I don't have the list at my fingertips,

but the point is that each one of them requires an individual

waiver that may not be granted, and which in any case adds to

the overall administrative workload for the assistance programs.

Section 907 prevents us from doing many of the things we should

be doing to advance American interests in Azerbaijan and to assist

Azerbaijan in developing towards prosperity and continuing stability.

For example, we can't sit down with Customs officials and devise

U.S.-funded programs to help them reform their customs structure

in a way that would make it friendlier to American business.

Because of the critical importance of an investor-friendly business

climate for American and Azerbaijani interests, we encourage

the American Chamber of Commerce (AmCham) to do this.

Fortunately, they've been quite successful and have enjoyed close

cooperation with the Azerbaijani customs department, but this

has been an ad hoc effort that should support and supplement

but not substitute for the carefully planned reform programs

that USAID has developed in other NIS countries.

Unfortunately, with 907 in effect, we are unable to fund needed

programs such as customs reform in Azerbaijan. Both American

business and our national interests would benefit from the development

of an investor-friendly climate here.

What about medicine?

That falls into the category of humanitarian assistance. We have

undertaken fairly extensive health programs, particularly those

involving the health of lactating mothers and children's health

programs. Those types of programs began with refugees but have

not been limited to that population.

Anything that can be considered humanitarian aid can be funded

under Section 907 as currently amended. Of course, in light of

the number of Azerbaijan's refugees and internally displaced

persons (IDPs), which is the largest per capita of any nation

in the world [approximately 1 million refugees in a population

of 8 million people], there is a need for far more assistance

than is allocated.

In time, that need will diminish as Azerbaijan develops its oil

and gas resources and acquires the capacity to better respond

to its own refugee problems. But that time will not come for

several more years. The inadequacy of our assistance levels is

especially glaring when compared to the much larger amounts given

each year to the other two South Caucasus nations of Georgia

and Armenia, which benefit from Congressional earmarks.

Earmarks?

An earmark is a decision by the Congress to designate specific

amounts of money to be appropriated under a particular bill.

For example, in the case of the Freedom Support Act, "x"

number of dollars are appropriated for Armenia, Georgia and the

Ukraine. After the earmarks have been subtracted, the remaining

funds are divided up among the nine other countries competing

for them, which is an allocation made within the State Department.

This is what Bill Taylor's office does. [See interview with Ambassador

Taylor in this issue.]

What about help in terms of educational processes, like providing

access to computers so that students and faculty can become more

informed?

Well, it depends on whether the assistance is going to a private

institution or a governmental one. If you look, for example,

at Western University in Baku, you'll see that we've helped set

up a fairly extensive computer center that is connected to the

Internet. We funded that. But Western is a private university.

You will also note that there is no similar American-provided

computer center at Baku State University, even though BSU is

a much larger university. Since it's an official government university,

we can't provide them assistance because of the restrictions

imposed by Section 907.

Also on the education side, we run health education programs

that are administered by NGOs within the refugee camps and villages.

What about agriculture? That's a huge area that needs to be

developed.

I agree. But again, we cannot work directly with governmental

structures. We are working with individual farmers, particularly

in regard to individual animal husbandry. In several parts of

the country, we've set up a farmer's credit association in conjunction

with veterinarian services to help maintain healthy livestock.

The credit association helps the farmers pay the vet's bills

and also serves as a forum for information exchange and livestock

service. Eventually, it will probably evolve to include a leather

tanning operation. We also help Azerbaijani farmers learn better

how to produce and how to market.

We are just about to launch such a program in Zagatala, in the

western part of the country. This is a lovely area! It's particularly

fertile country, somewhat mountainous, but it also includes a

broad, fruitful valley area that enjoys good water drainage from

the Caucasus. Farmers in that region raise mulberries, hazelnuts

and wheat. They breed cattle and produce leather, meat and dairy

products. They cut timber from the mountains. They used to have

a sizable cement factory there during Soviet times, which could

profitably be rehabilitated to satisfy the growing regional market.

So it was a very productive region in its day, and its economy

could be stimulated again. I hope that our programs will catalyze

this process. It already enjoys some cooperation with TACIS [a

European Union program that provides technical assistance].

What about science, scientific investigation or exchanges

like that?

This would be more difficult for us because it would require

cooperating with the Academy of Sciences. Again, the Academy

is a governmental structure and thus off-limits under the strictures

of 907.

Looks like the assignment here in Baku "ties your hands"

a lot.

Section 907 ties our hands, yes. Because of 907, the U.S. Ambassador

in Azerbaijan is required to achieve America's goals with one

hand tied behind his back. It certainly makes the job challenging-no

doubt about that.

But also, when you get U.S. NGOs involved, for example, instead

of carrying out the task directly with Azerbaijani personnel,

a lot of money ends up being eaten up just administrating these

programs. Of course, one could argue that somebody has to organize

these programs. But there's a big difference in funding American

administrators who have to fly back and forth to do the job,

compared to funding Azerbaijani administrators. To me, it looks

like you end up turning somersaults to do things that could have

been done more directly and more cheaply if you didn't have these

restrictions.

I have never actually addressed administration as a function

of cost. But certainly there would seem to be additional administrative

costs involved in dealing through a number of NGOs, rather than

directly through the Azerbaijani government if only because the

government's administrative costs are funded by itself.

What other areas are affected by 907? Oil, of course, is usually

taken care of by the oil companies themselves.

The U.S. government doesn't get involved in financing the oil

and gas development of the country. As you can see, the companies

are quite capable of financing their own activities - more so

than we are. We do provide political support and assistance for

American companies, however, and are prepared to provide quite

a bit more in matters involving pipelines.

Energy development in the Caspian basin is not the subject of

this interview, but I'm sure you are aware of the strong U.S.

commitment to multiple energy export routes from the Caspian

to market and especially to the Baku-Tbilisi-Jeyhan Main Export

Pipeline (MEP).

The U.S. government is prepared to offer substantial financial

support for this line. For example, the Trade and Development

Agency (TDA) is prepared to finance pipeline-related feasibility

studies.

In Ankara, we've set up an unprecedented form of cooperation

between TDA, OPIC and EXIM Bank, which we call the Caspian Finance

Center. Its purpose is to assist in financing worthwhile projects

for the development, primarily, of energy in the Caspian basin

area, and we are looking into pipelines now - where EXIM can

finance aspects of pipeline construction that involve American

materials, or OPIC could provide risk insurance, and TDA can

do feasibility studies.

That doesn't mean that we're going to finance the construction

of the pipeline. That would be done commercially by the companies

because frankly, that in itself is a test of whether or not the

pipeline will be a commercially viable entity. And if it isn't

commercially viable, neither we nor the companies would support

it.

What about the environment?

Provision of U.S. assistance to protect the environment in Azerbaijan

is also precluded by 907.

Can you give some examples of how it has hindered some projects

that you might have liked to be involved with?

The government here has its own environmental structures. For

example, they are trying to start a government-sponsored Environmental

University. University officials have asked us for assistance,

but we can't help them.

Were it not for 907, we would certainly consider their request.

We would also develop proposals on our own for USAID-funded programs

to assist Azerbaijan in the cleanup of the many toxic areas left

behind by the rape of the Azerbaijani ecosystem perpetrated by

the Soviet Union.

And we would probably propose ways to help them protect the endangered

Caspian sturgeon, which is the basis of their caviar industry.

But 907 will not permit us to do any of this. As you well know,

we all live on the same small, interdependent planet, and when

the environment is neglected, everyone suffers.

A wide range of environmental questions is being addressed by

this government as they routinely begin to clean up. They're

trying to ensure that the companies that locate here adopt and

adhere to environmental standards that are internationally recognized.

They want to protect their habitat at the same time as they develop

it. We have a lot of expertise on this subject in the United

States. We could provide them with advisors, information and

assistance, but we simply are not permitted to do so.

What about cultural projects?

Again, if it has anything to do with the government, it would

be impacted by 907. And then there's the whole question of our

relationship to the Azerbaijani military. Often, the United States

has a wide variety of assistance programs for militaries in other

countries. Some are lethal, some are non-lethal.

In this particular case, we have a two-fold problem. On the one

hand there is 907, and on the other, there is the fact that Azerbaijan

is still technically at war with Armenia. And so, even if it

were not for 907, we would be constrained by our general policy

of not militarily assisting states that are in a state of conflict.

We don't assist Armenia either, of course, when it comes to matters

related to the military.

Of course, there are cooperative programs under Partnership for

Peace (PfP) that are offered equally to both countries and to

all other PfP members as well. This is a NATO program to which

most of the former Soviet states, including Russia, belong. Because

it is funded by NATO, Azerbaijan's participation is not precluded

by Section 907. But I can assure you that none of our aid is

directed to the Armenian military.

But what about the patrol boats that will be coming to Azerbaijan

soon to use for guarding against narcotics trafficking?

We're not giving them to the Azerbaijani military - we're providing

them to Azerbaijan's maritime border guards, that is, their Coast

Guard.

Isn't that governmental?

Yes. But we're doing it on the basis of an exemption, a "carve-out"

from 907, that permits assistance in counter-proliferation activities.

Provision of the patrol boats is part of a very specific, very

narrowly focused assistance effort that will help Azerbaijan

control its territorial waters and prevent passage of weapons

of mass destruction, fissile material and other precursors of

weapons of mass destruction. The program can have no impact on

Armenia because, of course, Armenia has no coastline on the Caspian.

Let me make clear that American aid is carefully controlled.

A lot of people think that when it comes to international aid

that we just sit down and write a check to the government, and

then they go carry out the programs. In fact, Israel is the only

country in the world for which that level of cooperation resides.

With other countries, we agree on programs, we establish programs,

but we control the expenditure of the funding and we don't actually

give money. We provide advisors, we provide training, and sometimes

we provide "aid in kind", but we don't actually give

the countries direct funds.

Before we conclude this interview, I would like to re-emphasize

the importance of assistance to the development of a vibrant

and self-sustaining private sector in Azerbaijan - assistance

that is prohibited by Section 907.

It is absolutely vital to enhance and accelerate the transition

between the kind of controlled economy that Azerbaijan inherited

from the Soviets and the kind of free-market, investor-friendly

economy that Azerbaijanis would like to develop. In fact, they

must develop it, and they can develop it.

With the support of American USAID assistance programs and in

cooperation with Western business, it's vital to create an indigenous

middle class and create new wealth. Over the next 10 years or

so, Azerbaijan will become a very wealthy nation through the

development of its vast energy resources. The trouble with developing

a country solely on the basis of oil and gas rents is that the

money only extends to about 30 percent of the population at very

best, leaving a substantial majority outside of the umbrella.

If you don't have other development in the non-energy sector,

then you won't have a non-energy tax base, leaving the national

budget seriously over-dependent on a single sector of the economy;

plus there will not be sufficient employment outside the energy

sector. This, in turn, means that the majority of the population

won't be able to deal with the inevitable inflation that will

come about when a lot more money appears in the economy.

Very quickly, a situation develops in which there are oil-based

"haves" and non-oil based "have-nots". In

other countries, this sort of imbalance has led to severe political

consequences. This skewed situation is not something that Azerbaijan

wants for itself. It's something that the government is aware

of; they understand the risk and are taking steps to try to head

off this kind of problem. The United States could help them with

this - and we would like to help them with this-but we can't.

What would

be your advice to the new Ambassador in terms of 907? [Ross Wilson's

credentials as the new U.S. Ambassador to Azerbaijan were presented

in October 2000 after this interview was made].

I have held discussions with Ambassador Wilson and will do so

again when I go back to Washington before he comes out here.

We've talked about the problems that we are discussing here today

as well as other issues of the U.S. - Azerbaijan relationship.

He is well-versed on Azerbaijan both by virtue of his experience

as principal deputy in the bureau responsible for the nations

of the former Soviet Union and in the extensive preparations

required of all new ambassadors. I have every confidence that

Ross Wilson will make a superb ambassador, and I would not presume

to advise him further on how he should do his job.

It's too bad that 907 exists here, because when the Soviet

Union collapsed, I think the Azerbaijani people reached out to

embrace America. But as the years have passed, they're becoming

more hesitant and less trusting of the United States because

of this Congressional legislation.

I think that's true. I can understand the Azerbaijanis' difficulty,

particularly since we would like to cooperate more closely with

them as well. I think they aren't sure if they can trust us as

an honest broker. Always in the back of their minds is this nagging

question of whether they can truly consider us their friend if

this rather obvious legislative bias in favor of their regional

enemy continues to remain in effect.

For the United States, a stable, prosperous, democratic Azerbaijan

is key to the achievement of our policies and the protection

of our interests in the Caspian basin. But 907 takes away many

of the tools that we need to help Azerbaijan move toward those

goals. Yet for Azerbaijan, attainment of those goals is not fore-ordained.

Azerbaijanis live in a very dangerous neighborhood and need international

assistance to strengthen their position. If Azerbaijan fails

to succeed, the United States will fail in the Caspian basin

as well.

As I have often said, Azerbaijan is the keystone in the arch

of policy success for America in the Caspian. Without a successful

and cooperative Azerbaijan, there will be no East-West Energy

Corridor, no revived Silk Route, and no hope for stability in

the South Caucasus. A necessary step towards that stability is

the peaceful, negotiated settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh question.

It's no secret that the Armenian economy is in deep trouble,

and that at least half of the population of Armenia has emigrated

since independence. This is not the result of the Nagorno-Karabakh

war. After all, the Armenians won the conflict; it is they who

occupy one-fifth of Azerbaijan's territory, while none of their

territory is being occupied by Azerbaijan.

Nor is it the result of the "blockade" which has to

rank among the least singularly ineffective strategies in foreign

policy. The fact is that a great deal of trade passes between

Turkey and Armenia via Georgia and Iran.

At the same time, gasoline is cheaper in Armenia than in Azerbaijan.

Armenia, unlike Azerbaijan, is in a position to export electricity.

Armenia's weak economic state stems, in my view, primarily from

its lack of resources or markets for its Soviet-era industries.

The future of Armenia's economic advancement will be driven by

its participation in the economic development of the South Caucasus

region, and that development is driven by Azerbaijan and the

energy-producing nations of the Caspian basin. But until the

Nagorno-Karabakh question is resolved, Azerbaijan will not permit

Armenia to become a transit route for energy pipelines. Nor will

Armenian industries be revived to support oil and gas development.

Nor will Baku agree to the establishment of U.S.-funded regional

development schemes for the three South Caucasus nations.

The saddest thing about 907 is that it benefits no one in the

South Caucasus - not Azerbaijan, not the United States, not even

Armenia. The truth is, everyone loses. Even Armenians, who initiated

this law in the U.S. Congress denying aid to Azerbaijan, are

victimized by the continued imposition of 907.

Neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia can fully develop economically

until there is peace in Nagorno-Karabakh. There are many obstacles

to such a peace, but I can assure you that the problem will not

be resolved as long as 907 bars the way. Along with Russia and

France, the U.S. plays a broker's role in attempting to facilitate

a settlement. [The U.S. is a co-chair of the Minsk Group of OSCE

- Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe]. But our

task would be far less onerous and more likely to succeed if

907 did not cause the parties to question the capacity of the

United States to act as an honest broker in this affair.

The Clinton Administration has consistently opposed 907 and has

often called for Congressional repeal, without effect. I do hope

that the next Congress will be prevailed upon to repeal the effects

of 907, or that the next President will find it possible to waive

it.

We need to clear the decks - to untie my successor's hands so

that he and the foreign policy community in Washington can join

with the governments of the region in unfettered pursuit of our

many common interests.

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|