|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

66-69

With Iron Will and Determination

Forging

a New Strategic Industry - Baku Steel Company

Interview with

Paolo Parviz

by Pirouz Khanlou

Paolo Parviz, one of the most successful

foreign entrepreneurs in Baku, has dared to undertake another

major project - construction of the Baku Steel Factory, a steel-melting

factory that will recycle Azerbaijan's wealth of scrap metal

into reinforcing bars and steel billets. Parviz, an Azerbaijani

who was born in Iran and educated in the West, has been active

in Baku since 1993. He was the driving force in establishing

the city's world-class hotel complex - Hyatt Regency, Park Hyatt

and the Hyatt Towers. Next, he got involved with bottling Shollar

water. His group's investment efforts - one of the first in Baku

- have paid off, not just monetarily, but also in the personal

satisfaction of creating something valuable for the country. Paolo Parviz, one of the most successful

foreign entrepreneurs in Baku, has dared to undertake another

major project - construction of the Baku Steel Factory, a steel-melting

factory that will recycle Azerbaijan's wealth of scrap metal

into reinforcing bars and steel billets. Parviz, an Azerbaijani

who was born in Iran and educated in the West, has been active

in Baku since 1993. He was the driving force in establishing

the city's world-class hotel complex - Hyatt Regency, Park Hyatt

and the Hyatt Towers. Next, he got involved with bottling Shollar

water. His group's investment efforts - one of the first in Baku

- have paid off, not just monetarily, but also in the personal

satisfaction of creating something valuable for the country.

This is the second time that Pirouz Khanlou, Publisher of Azerbaijan

International, has interviewed Paolo Parviz; the first time was

after the completion of the Hyatt complex. See "Welcome

Mat for Foreign Investment, " AI 7.3, Autumn

1999.

Well,

it looks like you're at it again. It seems you couldn't sit still

after completing this extraordinary Hyatt complex. Now you've

started another bold venture, totally different from before.

Why a steel melting factory? How did you get involved with this?

The answer is simple. It's a new, young country that is creating

a lot of opportunities for development and investment. I got

involved because I think there's an opportunity to create a steel

industry in this country. The raw materials are here. Some skilled

workers are here. Strategically, it's in a great location for

the markets. And basically, we have been greatly encouraged by

the President and the Prime Minister to create this industry.

As to not being able to sit still: one has to get up in the morning.

One always wants to do something. It really makes no difference

what you do during the day as long as you do it well. It's a

project.

The idea for building a steel melting factory came to me when

I saw all of this raw scrap material for a steel melting industry.

The idea just came from looking around the country. Needless

to say, there's a great deal of scrap around here because Azerbaijan

had been a landlocked country; they couldn't export it to other

countries that could melt the steel. So that was good fortune

for this country, and there is a considerable amount of scrap

for years to come, so long as it is not exported.

So that was the greatest incentive. If you want to create an

industry in any country, you start from the basis of having the

raw materials for it. That was at the heart of the decision-making

process.

Where does the scrap come from?

Used metal products. Old factories. Under the Soviet system,

they weren't very conscious of the environment. As cultured as

the people were, on the other hand, they were very casual when

it came to taking care of the environment. Recycling as it is

done in the West is still a new concept for former CIS countries.

Above: President Aliyev at

the Opening Ceremony of the Park Hyatt Complex in 1999. Paolo

Parviz proudly looks on.

The steel industry is a mother industry that will provide opportunities

for other people to buy liquid steel from Baku Steel Company

and make other products out of it.

Steel is a basic industry, just like oil is for the petrochemical

industry. Besides that, it goes a long way toward cleaning up

the environment in Azerbaijan. Once steel is used, for example,

in an old car, it's very difficult to get rid of. You can't bury

it. In the West, they recycle these things and make new steel

out of them. So this industry will serve the country from an

environmental point of view as well.

What is the background of steel melting or steel factories

in this country?

There has not been a steel melting factory here. There have been

a considerable number of machine shops for producing equipment

and pipes for the oil industry. But these were all Soviet-built.

Most have been closed down because the conditions have changed,

the markets have disappeared and there are higher expectations

for quality. So they've stopped. But there are possibilities

to rejuvenate some of these industries.

What is the background of the building where you've set up

the factory?

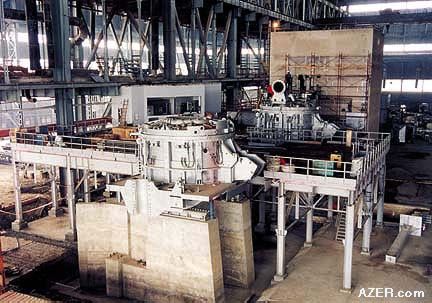

Above: Rebar manufacturing

section of the Baku Steel factory.

Originally, this building was intended to be a factory; it was

built in the 1980s to produce small airplanes. Then Moscow changed

its mind and decided to convert the factory to make large furnaces

for the entire Soviet Union. But it never really went into operation.

So we bought the factory, not for what it had been intended for

or for the equipment in it, but basically we bought the shell.

We needed a shell. Since all of these empty factories are here,

it would be silly to build another shell for a factory if you

can use an existing one.

We felt that it had the infrastructure. The factory never really

functioned for the purpose it was intended to serve. It just

sat there. Basically, the equipment was dilapidated. After upheavals

and the breakup of the Soviet Union, while Azerbaijan was being

rebuilt as a new country, the factory workers (the few that they

had) didn't receive any wages. So they basically cannibalized

the factory and equipment and took out the motors or whatever

they could find - the copper and metal - and sold it.

The result was disastrous, as you have seen. The equipment that

was left was not useful to us. We took all of the old equipment

out and replaced it with steel melting equipment: a 260,000-ton

capacity rebar mill, which is a larger capacity than the country

needs at this time, but there are neighboring markets where we

can export the steel.

How large is the factory?

We have 50,000 square meters under roof, but the property in

total is about 40 acres.

Above: German-made hearth

for melting down scrap metal.

Is there any other factory like this in the region?

No, not within 1,200 km. There are factories in Iran and the

Ukraine. These are the closest ones.

Are you using local know-how and workers?

Yes, an investment in a basic industry like steel or oil, not

only creates jobs within your own company, but it creates jobs

for other people in many other industries as well. I was told

that our work in constructing this factory has resulted in jobs

in Baku for 18 different companies in addition to our own crew,

which includes approximately 500 workers right now for building

the factory. These 18 companies have sizable contracts with us

in helping to build the factory.

As I understand, in terms of the machinery in this factory,

you're building it yourself rather than importing it from the

outside.

In the steel industry, obviously, there's some sophisticated

machinery that we've brought in from Germany, Italy and the U.S.

But some types of simpler non-machinery equipment, such as platforms

and cooling beds - which are simple to make - are produced here.

They're bulky and heavy. You can't afford to bring them from

Europe.

We have our own engineers. We get the designs and build them

here. Again, this process has created jobs for all of these people

during these past two years.

Above:

Steel melting

equipment with cutting-edge technology imported from Germany,

Italy and the U.S. Much of the steel structure of the Baku Steel

Factory was built by local industrial crafstmen. December 2000.

You talked about meeting environmental standards in this factory.

Anyone who has been exposed to the West is very conscious of

high environmental standards. I think the countries of the former

Soviet Union are becoming conscious of that more and more.

You can't produce steel in Baku and generate smoke these days.

So what are you going to do? It isn't right or fair. We've invested

more than $2 million in equipment alone, just for filtering out

smoke to make sure this factory operates up to European standards

- the best of European standards. That means we don't create

any smoke.

This is probably the biggest investment in the non-oil sector

that is being carried out in this country.

Yes, it is. More than $80 million, in two stages.

How did you come up with the idea? Did you wake up one morning

and say: "My Hyatt project is done."

Yes, this country offers a great deal of opportunities. I've

always received encouragement from the leadership of this country

to work here. It's not just money - it's the feeling of accomplishment

here. Nobody needs me in America and Europe. But I can be a little

bit more useful around here. I'm thankful that they give me an

opportunity to do something, so that when I wake up in the morning,

I've got a project. It's not always easy, but it certainly beats

getting up in the morning and having nothing to do.

It looks like you love to tackle the "impossibilities".

I'm just like most people. I like a certain amount of challenge.

If it's easy, it's not fun. Building a steel industry in this

country - or in any country - is certainly not an easy thing

to do. There are a lot of hiccups. There are a lot of problems,

a lot of rules and regulations that you have to overcome. But

I think that once you gain the reputation in this country that

you are sincerely trying to do something, you get help. I don't

really have any complaints about any individual authorities.

In fact, they are helpful and they don't get in my way.

Sometimes, there are some impractical laws and heavy bureaucracy

that have been left over from the old days. This can be cumbersome

and create difficulties, but we overcome them. It's a young country,

so I expect these things, and I've gotten used to them. In fact,

if they were eliminated and everything was perfect here, I think

I would miss them because I'm so good at handling them now (laughs).

Above: Baku Steel Factory

is housed in what was intended to be a factory but never went

into production because of the collapse of the Soviet Union in

1991. The equipment, though never used before, had been vandalized,

and parts sold.

A lot of people complain about these old rules and regulations.

In all fairness, I have certain advantages. I'm Azerbaijani myself.

I speak the language. I feel closer to the people. I kiss a lot

of men with mustaches around here to get the job done, I can

tell you that. And then you have to do a bit of screaming, a

bit of fighting, a bit of loving and you move things along. I'm

familiar with the culture. I like this culture. We are one and

the same people. That gives me an edge over an American who might

be landing here. They have the cultural barrier to overcome.

You didn't grow up in this country. Most of your life was

spent in the U.S. and Europe. How did you bridge the gap so fast?

I really think that it's in your blood. As you get older you

get closer to your roots. I was born in Iranian Azerbaijan. I

have certain sympathies for Iran. And yet I have a greater sympathy

for Azerbaijanis within Iran because we are a slightly different

culture. A Sicilian living inside Italy feels closer to another

Sicilian than to a Milanese. A Texan feels closer to a Texan

than to a Bostonian. It's all part of human nature. You feel

closer to your own people.

Would you encourage others to come here?

If it were easy and perfect, everybody would be here. It's difficult

- that's why everybody isn't here. That's the disadvantage. But

if you have the guts to come here, you can be first. Then you

get a better return on your investment, and you have an opportunity

to build something.

So would you even encourage people who don't have any background

to come here?

Absolutely. Come here. Be patient and put up with some of the

difficulties. This country certainly needs more investing workers

than Parviz in this town. I wish there were 200 of us. I wish

there were a thousand of us here to help to build the economy.

Then we would all benefit. People need jobs, and we need to develop

this economy as quickly as possible.

You've worked in a number of countries - the U.S., Europe,

the Middle East, Africa. Do you find these people are different

from those in other countries, especially those in developing

countries?

Well, I have my own definition for the former Soviet Union. There

are developed countries like the industrialized nations of Europe

and the United States. And then there are the underdeveloped

countries, like in the Middle East and Africa. But when it comes

to the former Soviet Union, I call it "mis-developed".

They were extremely advanced in certain areas - they were the

first to go into outer space. On the other hand, they were extremely

weak in the consumer product industry.

There is education; there is culture. The education level in

Azerbaijan is higher than in Iran and Turkey. But because of

the system, the initiative was not there. Decision-making was

centralized. They've always made collective decisions. Everything

was collective, including decision-making. When everything is

collective, it's inefficient.

How does that affect your work today?

I go beg. I go from Ministry to Ministry. I go to the Prime Minister's

Office. They are kind enough to receive me. I move my own papers,

because I can't work at their pace. When you undertake a project,

timing is crucial because you can lose your shirt in it.

In capitalism, the investor must make a return on his capital

or else he goes bankrupt. In the Soviet Union, there was no such

thing as bankruptcy, except that the whole country went bankrupt.

There was no such thing as individual bankruptcy; it was a collective

bankruptcy. They all went bankrupt together - everything.

What difference do you see now with individual workers, given

these Soviet hangovers from the past?

They are very good people. They are very appreciative of having

jobs. I think we treat them decently. We pay them better wages

than anybody else in town. They work hard. We're happy with them.

How would you compare this project with the Hyatt complex?

What are the differences? What are the similarities? Because

that, in itself, was also a major pioneering project.

Different businesses have different difficulties. But a project

is a project. When you wake up in the morning wanting to do a

job, it makes no difference. You solve the problem of the day.

There are no standard problems. If there were, there wouldn't

be any problems, would there? If we knew what the standard problems

were, there wouldn't be any because the geniuses of the world

would have eliminated them. No matter how many problems you solve,

there is always a new one.

But this is life. That's what human beings are marvelous at-we

solve the problems as we go along, and we create some if we don't

have any.

Do you get tired of resolving these problems?

Of course, I get tired. But I go to bed and sleep well and get

up in the morning. You get addicted to solving problems. In fact,

if I don't have any, I create some myself. Your total nervous

system gets used to solving problems.

You've played an important role in this country, being part

of the development of this country after it gained its independence

[1991]. How do you see the future of this newly independent country?

You need a sense of history before you can pass judgment about

the present or the future. If you take a look at when you and

I first came here seven years ago, there were no shops. There

was no bread.

There really weren't even any stores - just a few government

shops that were mostly empty. If you take a look at what has

been achieved in the last six years, it's amazing. Today, you

can find anything in this town. In other words, the shop-keeping

economy started only about seven years ago when they didn't even

have any bread available in the morning. This is a monumental

achievement.

If somebody had told you seven years ago: "We plan to open

15,000 shops in Baku," you would have said: "Oh my

God, forget it! How can you open 15,000 or 20,000 shops in five

years? Impossible."

But this is a perfect illustration. If you give liberty to people

and stability to the society, people solve their own problems.

The government didn't build these 20,000 (or however many) shops

that exist today. The people did.

Shops opened. Bazaars opened. You can find whatever you want

in this town today. All the leadership has to do is to create

enough stability and security for people to open shops and do

the job. This is a perfect example of what happens when people

have the chance to solve their own problems.

In Baku, you can find everything: clothing from Italy, Europe,

whatever you want. The people did this. That's why the old system

didn't work. Everybody sat on their hands and waited for the

government to do it.

How do I see the future in this country? As long as there is

political stability, people will find a way. The laws will change;

the bureaucracy will become less cumbersome. But it takes time

to transform a country from a state-controlled Communist-Socialist

system of economy to capitalism. Even if you change the laws,

a great deal depends on the mentality. Naturally, the bureaucracy

doesn't want to let go because the government has always controlled

the power.

In democracy and capitalism, the power is supposed to be in the

hands of the people. It takes time for that to develop. In a

person's lifetime, five or ten years are a long time. But in

the life of a country, ten years is nothing. Considering the

achievements that have been made these past six or seven years,

I would say it's because of the political stability that the

leadership has created in this country. And that's why I'm very

optimistic.

Do you have any plans to retire?

No, I'm too busy to retire. I don't have time. I'm having fun

doing these things. Retiring for me would be like queuing up

in line to be hauled away. So no, it's not on my agenda.

______

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|