|

Spring 2001 (9.1)

Pages

42-45

Alim Gasimov

Master of Mugham

by Betty

Blair and Pirouz Khanlou

More: Alim

Gasimov's Latest Concert in Tabriz

More: The

Poetry of Mugham

Alim Gasimov's (1957-

) career as a mugham singer nearly ended at age 14. He'll never

forget the humiliation he felt while competing in a local music

contest; when he started singing what he figured was mugham,

the audience started laughing at him. Alim stepped down from

the stage with tears in his eyes. Fortunately, he didn't give

up on mugham. Alim Gasimov's (1957-

) career as a mugham singer nearly ended at age 14. He'll never

forget the humiliation he felt while competing in a local music

contest; when he started singing what he figured was mugham,

the audience started laughing at him. Alim stepped down from

the stage with tears in his eyes. Fortunately, he didn't give

up on mugham.

Twenty-eight years later, in 1999, Alim won the prestigious UNESCO

Music Prize, one of the highest international accolades that

a musician can hope for. Previous laureates have included Dmitri

Shostakovich, Leonard Bernstein, Ravi Shankar and Nusrat Fateh

Ali Khan.

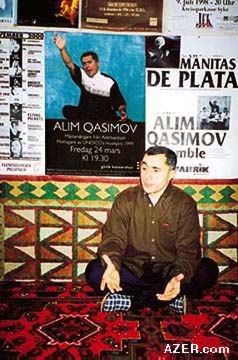

Left:

Singer and

UNESCO International music prize winner Alim Gasimov at home,

surrounded by posters of his mugham concerts.

As the foremost mugham singer in Azerbaijan, Alim has recorded

nine albums and lately has been featured quite frequently in

Azerbaijani newspapers and TV programs. He has performed in France,

the U.K., Germany, Belgium, Spain, Brazil, Iran and the United

States.

Alim is attracting many new fans to mugham. Russian-educated

Azerbaijanis and young people in general don't usually care much

for the mugham genre. Many prefer listening to Western pop music.

But surprisingly, they have been going to Alim's concerts and

buying his CDs.

Azerbaijan International is honored to have this chance to delve

more deeply into the world of Alim Gasimov. We talked to Alim

about how he puts his individual, innovative stamp on traditional

Azerbaijani music.

______

What is mugham?

To Azerbaijani singer Alim Gasimov, this traditional music is

"food for the spirit." "Mugham [pronounced moo-GAHM]

is something sent from God," Alim explains. "It was

created together with humanity. You can't create it anew."

More specifically, mugham

consists of Azeri, Persian or Arabic poems - mostly love songs

- set to improvised music. The lyrics are written down, but not

the music. Depending on the specific mode of mugham being played,

the improvisation traverses a designated number of tetrachord

sequences, for example, three tetrachords consisting of 2 half-steps

and one full-step, or vice versa. The improvisation for one mugham

may continue for 30 minutes to a few hours. More specifically, mugham

consists of Azeri, Persian or Arabic poems - mostly love songs

- set to improvised music. The lyrics are written down, but not

the music. Depending on the specific mode of mugham being played,

the improvisation traverses a designated number of tetrachord

sequences, for example, three tetrachords consisting of 2 half-steps

and one full-step, or vice versa. The improvisation for one mugham

may continue for 30 minutes to a few hours.

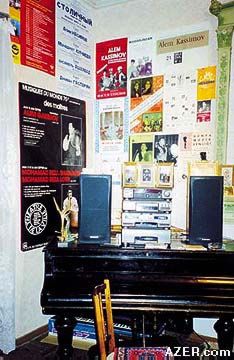

Left:

Alim Gasimov

has sung mugham in many corners of the world, as you can tell

from the concert posters that wallpaper his apartment.

Some people suggest that the word "mugham" derives

from the Arabic word "maqam", which refers to an official

meeting place where medieval caliphs and other Arabian dignitaries

gathered to hear tales and rhyming prose, and later music as

well.

In the early 20th century, Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov

identified seven main mughams (rast, shur-shahnaz, seygah, bayati-shiraz,

humayun, heyrati and chahargah) plus five secondary mughams.

Each mugham is said to be connected with a certain feeling or

emotion; for example, "seygah" represents grief and

"shur-shahnaz" stands for tenderness. But Alim claims

that mugham is not as simple as that: "You can't attach

strict theory to mugham," he insists. "For example,

some say that 'chahargah' reveals the spirit of fighting and

war. But I say that it reveals the feeling of spiritual elevation

instead."

Alim maintains that he doesn't have a favorite mugham modal form.

"I feel the nature, the character, the smell and the color

of each one. For me, each of them is like a human being with

its own personality. You have to understand them from within.

If you have the capability to see them, you can follow them even

to the stars. Maybe this is what enables the spirit to transcend

the body. I believe in the spiritual world. I believe it never

dies.

"I want to see mugham as a world of spirits. The spirit

is incomprehensible, God is incomprehensible. It's not like mathematics,

where you have a formula like two plus two is four. That would

make it finite.I want to see mugham as something inexhaustible.

From this point of view, I don't want to say that 'seygah' expresses

grief, or 'shur' expresses tender feelings, and that's it. Mughams

express a myriad of complex feelings."

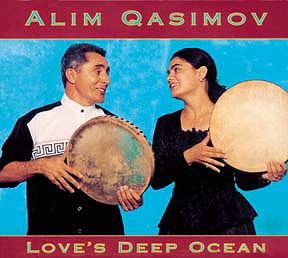

Alim Gasimov and his 21-year-old daughter Fargana have recorded

three albums of mugham music together.

Ancient Poetry

When deciding upon lyrics for mugham, Alim chooses ghazals (poems

with an Eastern meter) by classical poets such as Khagani, Fuzuli,

Shirvani and Sabir. "I used to choose the words that earlier

mugham singers performed," he recalls, "but I don't

do that anymore. I select the poetry myself now."

Alim has one condition for selecting a poem - it has to touch

him emotionally. "I read the poem and if it makes my heart

tremble, I choose it. Some poems are not accessible for me. I

don't get meaning from them."

Left: Alim Gasimov and his 21-year-old daughter

Fargana have recorded three albums of mugham music together. Left: Alim Gasimov and his 21-year-old daughter

Fargana have recorded three albums of mugham music together.

The

interpretation of these poems depends largely upon the listener.

For Alim, the poetry is about philosophical notions rather than

lyrical love. "You can say they deal with love," he

says, "but everybody interprets them in his own way. This

is very important in mugham; since the music is independent of

a strict framework, the poetry should be so, too.

At a young age, you might interpret the poems as talking about

love for a beautiful woman.

The older you grow, the more philosophy you see in them. An older

person, for instance, might interpret these poems from a Sufism

point of view."

Some of the poems are in Arabic or Persian, which means that

Alim doesn't know the meaning of every single word. "Maybe

I can't always identify the exact meaning of the words,"

he admits, "but I feel and understand by intuition what

they imply. Maybe it's even better that I interpret the poetry

myself. The word touches my heart and then 'lights a torch' there."

Modern Mugham

According to Alim, there is a huge difference in the way contemporary

singers do mugham as compared to earlier performers: "Mugham

performance has been changing throughout history. At the beginning

of the century, we had Seyid Shushinski and Jabbar Garyaghdioghlu.

Today we have our contemporaries. But I think today's mugham

is actually closer to earlier forms. Now we're singing more like

the mugham that was performed at the beginning of this century.

"Although one particular person may introduce a certain

improvisation, it can influence an entire generation. It's like

fashion - one person introduces it, but then it enters and affects

the performance of others."

Alim realizes that his style of mugham is not like that of his

contemporaries. "I may perform differently from others and

stray from the usual traditional patterns. For those who like

that, they might say, 'He's a breath of fresh air.' But others

criticize me and say that I'm destroying the tradition of mugham

performance."

Unlike other Azerbaijani mugham singers, Alim sits cross-legged

on the floor. Some Azerbaijanis don't like this, even though

it is an Eastern tradition to perform that way.

Alim also plays the gaval differently from most mugham singers.

The gaval is a tambourine - like percussion instrument that the

singer uses to set the tempo for the accompanying tar and kamancha.

"I never practice the gaval beforehand," Alim says.

"It just comes naturally. It comes from inside me. I don't

know how I come up with such rhythms. I don't calculate them

beforehand. In the past, I used to perform the traditional pattern,

but I wasn't able to continue it. It would have exhausted me.

I listen to my heart, and that gives the rhythm of the gaval

a certain freedom."

Besides the singer and his or her gaval, mugham also features

two more instruments: an 11-stringed tar and a three-stringed

kamancha. Alim is accompanied by two brothers from northwest

Azerbaijan, Malik Mansurov on tar and Elshan Mansurov on kamancha.

But he recently expanded upon this traditional grouping to include

a naghara (a metal-bodied drum), a clarnet and a double-reeded

balaban as well. The balaban is a pipe instrument that can produce

plaintive sounds much like the sustaining notes of a bagpipe.

The musicians in Alim's ensemble are relatively young. He selects

them because they don't play mechanically. "I think they

feel the same thing as me spiritually," he says.

Improvisation

At its heart, mugham is about improvisation - an ocean of musical

and emotional possibilities. "You swim and swim and it never

ends," Alim explains.

He believes that improvisation means choosing a way of life -

a way of living in mugham. "For example, when you go to

a birthday party, you take a gift. But not everybody takes the

same gift. One person can take a bunch of flowers, another, a

box of chocolates, somebody else creates a painting. Through

mugham you convey certain feelings. Improvisation is selecting

a way to convey those feelings."

As with other types of music, practicing is still crucial for

this improvisation. "The pieces we perform are not simple

songs," Alim points out. "We have to practice and practice.

And what's more, every time we practice, we find more nuances.

This is also how improvisation works."

Listening to Mugham

Mugham is not an easy genre to understand, especially for a non-Azeri

speaker. For those who are new to mugham, Alim suggests listening

for the following things: "First of all, pay attention to

the timbre and quality of the singer's voice as well as the emotions

it produces. Also, make sure to pay attention to the improvisation

and the range of the voice."

For Alim, it's actually easier to sing mugham for foreigners

because they are less familiar with the genre. "When I'm

performing abroad, I feel more comfortable," he explains.

"In Azerbaijan, something keeps me from throwing myself

into my own world. Here, the audience knows 90 percent of what

I sing. And there are professionals in the audience, which places

a huge responsibility on me to meet their expectations. I feel

I have to measure my every step."

Starting Out

Alim discovered the world of mugham as a child, when he began

singing for his own enjoyment. He grew up in the town of Shamakhi,

100 km northwest of Baku. "I had no idea that I would become

a singer," he remembers. "Nobody in my family influenced

my career, at least not directly. My father has a good voice,

but he's not a professional." Alim's father occasionally

sang at Azerbaijani wedding parties, where musicians will often

sing or perform for hours at a time.

While Alim's parents recognized that he had musical talent, they

were too poor to buy him a musical instrument. Instead, they

did the next best thing. "My father killed one of his goats

and took the animal's stomach membrane and stretched it across

a frame to create a frame-drum for me," Alim recalls.

It soon became clear that music was more than just a hobby for

Alim. "Actually, I didn't have any other choice besides

music," he confesses. "I didn't have any other talent,

and I couldn't see myself doing anything else. I was faced with

the harsh reality - either singing or nothing."

Alim does admit, though, to qualities within his mother and father

that have influenced his path. "My mother is very energetic,"

he says. "She's a woman who sparkles. My father has a beautiful

voice, but he sings only for himself. He's quiet and calm. So

I guess I took my mother's energy and my father's voice. For

me to have been born, they had to be together. That was God's

will. Whatever has happened in my own life has been shaped by

destiny. I am being led by destiny, I feel this."

When asked about other interests and passions outside of performing

mugham, he admits, "I can't find comfort anywhere else or

in anything else. I get bored quickly. I guess it's fair to say

that my only world is music."

Soviet-Era Mugham

Alim studied at Baku's Asaf Zeynalli Music College from 1978

to 1982. His teachers included Seyid and Khan Shushinski, Zulfu

Adigozalov, Hajibaba Huseynov and Agha Khan Abdullayev. At age

25, in his second year as a professional mugham singer, Alim

won Azerbaijan's Jabbar Garyaghdioghlu Singing Competition.

During the Soviet period, when Alim was studying music and beginning

to make his way as a professional singer, the official attitude

toward mugham was not very supportive. According to Alim, the

Soviets treated mugham as an unimportant folk art: "Mugham

was performed just to show that we Azerbaijanis had this relic

in our history. The Soviets wouldn't allow long performances

of it. Of course, certain singers tried to protect mugham even

under these restrictions."

Back then, it was unusual for a musician or any other person

to travel outside of the Soviet Union. "If someone made

a trip," Alim says, "there would be announcements on

TV and articles about it. People were very excited about journeys

and tours, and everyone would come out to see that person off.

But these days, it's not such a big deal. We come and go and

hardly anybody knows about it."

The Next Generation

Today Alim and his wife, Tamilla Aslanova, live in an Oil Boom

residence that dates back to the early 20th century and has been

carved up into many apartments, as was the custom during Soviet

times. Their living room with its high ceilings is literally

wallpapered with large posters from Alim's many performances

around the world. Tamilla serves as his manager and helps to

document events and maintain the scrapbooks of his performances.

They have three children: a son, Gadir, and two daughters, Fargana

and Dilruba. Fargana, who is now 21, has been performing mugham

with her father for the past five years.

"When Fargana was as a baby, she used to cry a lot,"

Alim recalls. "I would sing mugham to calm her down. Once

she started talking, I taught her ghazals [poetic form used in

singing mughams]. I could see that she had potential in her voice,

and that's when I started teaching her to sing."

Fargana recalls: "I remember my father saying to me, 'When

you grow up, we will sing together.' Then in 1996, he took me

to one of his concerts in Germany. Everything started from there."

Surprisingly, the two of them don't practice very much together,

even though Fargana lives at home with her parents. "We

understand each other very well," Alim says. "We don't

need to practice together a lot."

When Fargana decided to study music at Baku's Music Academy,

Alim began teaching there. "I want Fargana to be more educated

than I am," he explains. "I'm more experienced in music

than she is, but she has a stronger theoretical base than I do.

Now I'm trying to pass my experience on to her.

"We have wonderful teachers of mugham here in Azerbaijan.

But many of them can't perform it. They know theory brilliantly.

As for me, I have to admit that I don't know theory. My knowledge

and feelings come from the singing and performing of mugham itself.

Actually, I don't accept too much theory in mugham. Somehow I

feel that it takes away from the spontaneity of the spiritual

world."

When asked about Uzeyir Hajibeyov's influence on mugham, Alim

says he sees him as a great personality: "I don't think

I should express opinions about him. I haven't read his book

['Principles of Azerbaijani Folk Music', which is even available

in English]. The musical theorists should speak about this, not

me."

UNESCO Prize

Alim won the UNESCO Music Prize in 1999, which he says was a

complete surprise: "Actually, I didn't believe it when they

told me I had received it.

"I think of the UNESCO prize as a reward for my dedication

to art," he continues. "I've never deceived anyone

when it comes to music. Maybe in life, I've made mistakes, hurt

people or told lies. But my attitude toward my art has always

been very sincere, very genuine.

"What I mean by that is that I have never treated music

as a source for gaining an audience. I've always sung the way

I felt - the way I wanted. I could have changed my direction

to fit my audience, but I haven't. I've always sung and acted

independently - the way my heart wanted. As Fargana reminds me,

I've always sung the same way, whether there were three people

in the audience, or a thousand.

"Sometimes my relatives tell me to relax, not to knock myself

out so much, not to kill myself at concerts. I nod in agreement

with them, but when it comes to the actual performance, I never

manage to restrain myself. Unless you sacrifice yourself for

art, it doesn't come alive for you."

Music and Mysticism

Alim's singing is marked by extreme intensity and concentration.

"When I sing, it seems like I leave the physical world,"

he explains. "I feel myself entering a different world,

a spiritual world-as if there is no materiality. I feel so good

and comfortable there; I would love to stay there forever. But

unfortunately, when I finish singing, I suddenly return to this

world.

"Sometimes this feeling just comes - it's not dependent

upon whether I want it or not. I understand that you have to

be so pure, so clean and so honest to gain access to this other

world. Somehow it seems to border between life and death as we

know it. There have been several times when I have felt myself

on that borderline.

"I don't know if this can be traced back to roots in Sufism,

to Nasimi Mansur Hallej, for example, and his conviction that

you can forget your physical existence and act 'outside your

physical being.'

"To tell you the truth, I am almost unaware of the world

of Azerbaijani philosophers. For whatever level I have attained,

I have reached it on my own experience. Maybe I'm lucky that

I'm unaware of these things on a theoretical basis; maybe that

makes it more natural for me. Somehow I just seem to intuit these

things.

"Actually, human beings are amazing, they spend their entire

lifetimes on a journey discovering themselves. Suddenly you find

yourself doing something that you don't expect of yourself, meaning

that you don't fully know yourself. I'm constantly at war with

myself, as if there is another 'me' inside of me."

Alim believes that mugham can have a purifying effect on both

the singer and the audience. "It cleanses you from inside

and makes you purer," he explains. "It makes you pay

attention to the eternal things in life. I believe that mugham

has tremendous power - I'm convinced it can even prevent criminals

from committing crimes. There's no place for hatred in your heart

when you listen to mugham. It works upon your soul.

"Sometimes young people come up after a concert to thank

me. That's like giving me wings. I feel so elated when I can

awaken such feelings in people while they are still young; mugham

is not an easy genre for young people to understand.

"When I see my audience taking a trip into a spiritual realm

together with me, I feel happy. This is the greatest reward in

my life."

Alim Gasimov's latest CD, entitled "Love's Deep Ocean"

(no Azeri title), features him and his daughter Fargana;

the album was released in Frankfurt by Network Medien. In the

near future, samples of Alim and Fargana's music may be heard

at Azerbaijan International's Web site at AZER.com. Click on MUSIC. Jala

Garibova also contributed to this article.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.1) Spring 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.1 (Spring 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|