|

Spring 2001 (9.1)

Pages

25-27

Resolving Nagorno-Karabakh

Can It Be Done?

by Yoko Hirose

Ms. Yoko Hirose (Master

of Law), a graduate student in the University of Tokyo's doctoral

program, was among the first four recipients of a newly established

grant - the Akino Memorial Research Project on Central Asia from

the United Nations University (UNU) in Japan. Ms. Yoko Hirose (Master

of Law), a graduate student in the University of Tokyo's doctoral

program, was among the first four recipients of a newly established

grant - the Akino Memorial Research Project on Central Asia from

the United Nations University (UNU) in Japan.

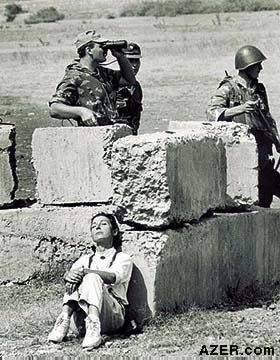

Photo:

In May 1994,

a ceasefire was signed between Armenia and Azerbaijan. But each

year, hundreds of casualties still result.

The first fellowships were awarded in 1999. This past year (February

2000 to March 2001), Yoko lived in Baku conducting research on

the topic of "The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: In Search of

a Peaceful Settlement of Ethnic Conflict in the Former USSR".

In April 2001, she returned to Tokyo for her new responsibilities

as Research Fellow for the Japan Society for the Promotion of

Science, Graduate School of Law and Politics at the University

of Tokyo. Here Yoko shares her insights into the conflict between

Azerbaijan and Armenia and what she thinks are the prospects

for reaching a peace settlement.

This past year, I have been living in Baku and conducting research

about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It's been so valuable to

interview scholars, journalists, politicians, diplomats, refugees

and students about their opinions related to the conflict, from

both the Azerbaijani and Armenian sides.

Azerbaijan's Stand

The Azerbaijani explanation of the conflict is basically as follows:

They consider Nagorno-Karabakh as part of their motherland, the

birthplace of brilliant artists, poets and composers. Now it

has fallen prey to Armenian nationalism; many Azerbaijanis have

been killed but the remainder have been driven out of the region

- their homeland. They consider their ancestors to be Caucasian

Albanians, who were the aboriginal inhabitants of the region.

Azerbaijanis say that historical documents prove that Armenians

were transplanted en masse to the region quite recently - only

2.5 to 3 centuries ago.

Azerbaijanis believe Armenians have no legitimate right to insist

on independence or in uniting Nagorno-Karabakh directly to Armenia

itself. However, Azerbaijanis are willing to allow some autonomy,

especially in the use of the Armenian language - not only officially,

educationally and culturally - but also in mass media.

Azerbaijanis told me that they used to get along well with Armenians

as neighbors. Proof of that reality is the considerable number

of couples who intermarried (usually Azerbaijani men with Armenian

women). But then this problem of land acquisition began to erupt

just as the Soviet Union was collapsing (late 1980s). Of course,

roots go back to the early decades of this century, even before

the Soviets took power. Many Azerbaijanis told me how Armenians

who had been living in Azerbaijan had suddenly disappeared without

even saying goodbye [1988-1991], even those who had been their

closest friends. Even now, many Azerbaijanis cannot comprehend

how attitudes changed so quickly and became so hostile.

Another important factor that duly affects the developments related

to war and its peaceful resolution center on the events that

took place in Sumgayit. Mystery and rumors still shroud the events

that took place there on February 28-29 in 1988, when 26 Armenians

were killed (along with 6 Azerbaijanis and 1 Lezgin), according

to the official count.

However, this doesn't stop the Armenians from using the outbreak

of violence in Sumgayit as their rationale for attacking and

seizing Nagorno-Karabakh. However, the Azerbaijanis posit that

the Sumgayit incidents were masterminded and instigated, not

by Azerbaijanis, but in a well-calculated plan carried out by

the KGB and Armenian terrorists.

While the KGB involvement will never be possible to prove, the

Armenian involvement is known - as the Armenian perpetrator and

murderer has actually been named - Grigoryan. They also believe

that President Gorbachev turned a blind eye or even helped to

facilitate the turmoil. More important from the Azerbaijani point

of view is that these events were triggered and clearly linked

to the murder of two Azeri youth (Bakhtiyar Uliyev, 16, and Ali

Hajiyev, 23) by Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh on February 24,

1988-assasinations that preceded the Sumgayit tragedy.

Regardless of how or why the attacks started in Sumgayit, Azerbaijanis

insist that most of them did not participate in these unfortunate

events, and that many of them even protected Armenians instead.

Had they not done so, they say that the Armenian casualties would

have been much higher. Azerbaijanis are angered that Armenians

use this situation as propaganda (often referring to it as "pogroms"

or "genocide") to rationalize and gain international

sympathy for their attacks on Nagorno-Karabakh.

Many people in Baku said that they don't hate Armenians as people;

they want to build good relations with them, if possible. However,

they disagree with the actions of the Armenian government in

general. They strongly believe that Nagorno-Karabakh belongs

to Azerbaijan and should remain so. Many adamantly oppose making

any concessions to gain peace.

Refugees' Perspective

Azerbaijani refugees (of whom there are nearly a million) are

much more emotional and unrelenting toward Armenians. They say

that even though they had not shown any prejudice against Armenians

before the conflict began, Armenians took their motherland away

by driving them out and killing them. They believe that Armenians

were motivated chiefly by selfish interests.

The Azerbaijani refugees insist that they should be allowed to

return to their villages and towns in Nagorno-Karabakh and the

outlying regions that presently are still under Armenian military

occupation. They visualize international peacekeeping forces

being stationed to guard what could potentially be a very volatile

situation.

If such a peace plan were to be agreed upon, Azerbaijanis say

that they would allow Armenians to use Lachin as a corridor to

link the isolated enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh directly to Armenia.

Fast or Slow

The Azerbaijani newspaper Zerkalo recently conducted a poll of

nearly 5,000 Azerbaijanis, asking if they thought a peace settlement

would be reached within five years: 61 percent agreed, 38 percent

disagreed. But my own research would indicate that most Azerbaijanis

are not optimistic about a quick solution. Many people say that

it will be impossible to reach a settlement soon, because the

memories of the Armenian invasion are still too painful and fresh.

Too many people have been killed, pushed off the land and still

nearly 20 percent of Azerbaijan's territory is under occupation.

That's the Azerbaijani perspective. But I was eager to find out

first-hand how the Armenians felt about the situation, so in

the last two weeks of January 2001, I traveled to Armenia.

My journey was via Georgia, where I found that the youth are

really proud of their country and have extremely negative feelings

toward Russia and Armenia. They feel that Russia has treated

Georgia very badly, especially in regard to the visa regime that

has recently been imposed, the Russian military bases that are

still operating in their country despite promises of closure

and Russia's support for separatist regions of Abhazia and Ossetia

inside Georgia.

The youth say that they won't yield to pressure from Russia and

are ready for fight for their motherland. For them, the problems

of Abhazia and Ossetia, both of which are at a stalemate right

now, are extremely serious situations.

Georgians fear a second Karabakh on their territory and are concerned

that Armenia might use military force to claim pockets of land

where Armenians comprise the majority-just as they did in Azerbaijan.

Georgians also have very strong feelings against Armenians. For

example, when I brought Armenian cognac to a dinner hosted by

my Georgian friends, most of the guests wouldn't drink it because

it had been produced by "the enemy". The Georgians

are sympathetic with Azerbaijanis and hope that the Nagorno-Karabakh

conflict will be settled peacefully.

Armenian Attitudes

Then I traveled on to Yerevan, where I stayed in a dormitory

at the University of Yerevan and talked with many Armenian youth.

I was shocked by the hateful attitudes that I found in Armenia.

From childhood, they are taught to hate Azerbaijanis and Turks

(these two nations are the same in their minds). I found Armenians

to be very narrow-minded, nationalistic and unwilling to make

compromises. I am so sorry, I came across no exceptions.

They told me that there is no need for a settlement, because

Nagorno-Karabakh (and even Nakhchivan) should belong to them.

I asked them, "If Nagorno-Karabakh should be yours, then

what about the six surrounding regions of Azerbaijan that are

still being held as a buffer zone by Armenian military forces?"

They replied that those regions should also belong to them since

they won the war.

I found that many of them despised ex-president Ter-Petrossyan,

describing him as "weak-kneed" because he had tried

to find a way to compromise and enter into peaceful relations

with Azerbaijan. Many held the current president Kocharian in

high esteem because he is from Karabakh and has very strong feelings

against Azerbaijan. When I tried to introduce the Azerbaijani

perspective, they got very angry and insisted that I had been

cheated and tried to explain the truth that they believed.

It is very regrettable situation. I think that it will be very

difficult for peaceful relationships to develop in the Caucasus

for a long time. It may even take a century to settle this conflict,

because the ill feelings run so deep on both sides. In Japan,

our older generations still have very intense feelings against

the United States because of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima

and Nagasaki in 1945. Japanese youth, on the other hand, appreciate

and like the United States and are eager to study English.

In the Caucasus, it is the youth who will have to make peace

and develop this area. I know it will really be difficult, but

I hope and expect that it will eventually happen. Also, I'm convinced

that another factor is essential if peace is to be established

in the region. The international community must take a neutral

position and earnestly seek to cooperate in its settlement. So

far, this does not seem to have happened, as the major players

(Russia, France and the United States as co-chairs of the Minsk

Group of the OSCE - Organization for the Security and Cooperation

in Europe) generally have expressed a solution that tilts in

favor of Armenia.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.1) Spring 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.1 (Spring 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|