|

Spring 2001 (9.1)

Pages

68-71

Innovations

in Spoken Azeri

Sociolinguistically

Speaking - Part 9

by Jala Garibova

and Betty Blair

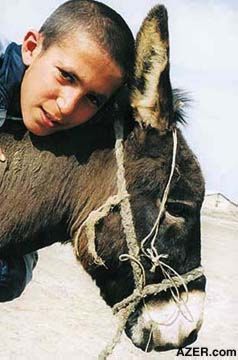

Photos of Refugee Children by Vugar Abdusalimov, UNHCR

With the collapse of

the Soviet Union in 1991 also came the end of the "information

blockade" - as Azerbaijanis often refer to it. The transition

period that followed has brought many new things, including basic

changes in infrastructure, the explosion of the Internet, exposure

to international media and the ability to travel to study and

tour distant countries. Since Azerbaijanis are being exposed

to so many influences, the Azeri language itself is changing. With the collapse of

the Soviet Union in 1991 also came the end of the "information

blockade" - as Azerbaijanis often refer to it. The transition

period that followed has brought many new things, including basic

changes in infrastructure, the explosion of the Internet, exposure

to international media and the ability to travel to study and

tour distant countries. Since Azerbaijanis are being exposed

to so many influences, the Azeri language itself is changing.

In this installment of "Sociolinguistically Speaking",

we attempt to "capture a moment in time" to describe

some of the most significant changes that we've observed taking

place in spoken Azeri today. Here we comment on some of the innovations

in language usage that we've observed in Baku. Since language

is such a dynamic phenomenon, six months from now, doubtless

there will be even more changes.

_____

Perhaps the most noticeable trends in spoken Azeri these days

can be observed in business offices, especially those where there

is considerable contact with foreigners. Even the etiquette of

something as simple as answering the phone is changing and becoming

more business-like and efficient.

In the past, the person picking up the phone would have likely

answered with a "da" ("yes" in Russian) or

("hello"

in Azeri). Today, there is a greater tendency to answer ("hello"

in Azeri). Today, there is a greater tendency to answer  (more polite form of "yes"

in Azeri) and then to add the company's name. More and more foreign

companies are adopting the policy of using Azeri when answering

the phone rather than their own native language (English, French,

German, etc.). This is a relatively new practice and unlike what

was happening when foreign companies first became established

in Azerbaijan in the early and mid-1990s. (more polite form of "yes"

in Azeri) and then to add the company's name. More and more foreign

companies are adopting the policy of using Azeri when answering

the phone rather than their own native language (English, French,

German, etc.). This is a relatively new practice and unlike what

was happening when foreign companies first became established

in Azerbaijan in the early and mid-1990s.

The person who answers the call is also likely to say,  , which roughly translates as

"Good all the time." This phrase substitutes for expressions

like , which roughly translates as

"Good all the time." This phrase substitutes for expressions

like  (Good morning)

or (Good morning)

or  (Good evening),

and is now being used as a generic greeting for incoming callers,

eliminating the need to identify the time of day. (Good evening),

and is now being used as a generic greeting for incoming callers,

eliminating the need to identify the time of day.

Unlike offices in the West, one shouldn't expect the person who

answers to say "How may I help you?", especially right

away. This could come off sounding rushed or pushy to an Azerbaijani,

especially to a caller who is not involved with the international

business community. Instead, after greetings are exchanged, the

person will often say " ,

which doubles for "Please" and "Go ahead"

(in a polite way). The phrase "How may I help you?" ,

which doubles for "Please" and "Go ahead"

(in a polite way). The phrase "How may I help you?"

may be used eventually,

but it's not typically used as part of the initial greeting. may be used eventually,

but it's not typically used as part of the initial greeting.

Caspian Bank, please / hello. Good all the time.

(Literally, Hello, we disturb you from AzFilm firm.)

Yes, please, how can I help you?

If the caller asks to

speak to a specific person, he or she might be surprised to have

to identify themselves, as is the usual practice in many Western

offices. This pattern is a newer development in Azerbaijani offices

and is not popular with some callers, especially if they are

from the older generation or hold a higher position than the

person they are trying to reach. If the caller asks to

speak to a specific person, he or she might be surprised to have

to identify themselves, as is the usual practice in many Western

offices. This pattern is a newer development in Azerbaijani offices

and is not popular with some callers, especially if they are

from the older generation or hold a higher position than the

person they are trying to reach.

One Azerbaijani woman who works at an international consultant

firm discovered that some people who call her are surprised and

a bit offended when the receptionist asks for their names. Recently,

one caller joked with her: "Are you the head of the office

nowadays? Is that why they wanted to know who I was?"

Caspian Bank, please/hello. Good all the time.

Hello, May I speak to Farid?

Excuse me, who is asking?

New Words

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, both Azeri and Russian

have absorbed many neologisms-that is, new words or expressions.

Some foreign words, such as " and

and  (disco), were

already being used during Soviet times. Similarly, the word "super"

was already used in both Russian and Azeri, usually as a prefix

in words like "supermarket" and "superman".

"Super" is pronounced SU-pehr. (disco), were

already being used during Soviet times. Similarly, the word "super"

was already used in both Russian and Azeri, usually as a prefix

in words like "supermarket" and "superman".

"Super" is pronounced SU-pehr.

Newer additions to the language include "gym" and "club".

However, when Azerbaijanis speak of Baku's "Hyatt Club",

the vowel in "club" is pronounced like the vowel in

"clue".

Newer, upscale hotels like the Hyatt or ISR Plaza are referred

to as  , whereas Soviet-era

hotels like the Absheron and Azerbaijan Hotels are still referred

to by the Azeri word - , whereas Soviet-era

hotels like the Absheron and Azerbaijan Hotels are still referred

to by the Azeri word -  (literally,

guest house). (literally,

guest house).

Especially in the political and business spheres, both Azeri

and Russian have incorporated new words such as "visit",

"ex-President", "speaker" and "Parliament".

Sometimes these new words don't represent new concepts, but rather

reflect a new environment, such as a new type of office. Examples

of this include "manager", "file" and "folder".

In the business world, the English word "training"

is replacing the Azeri equivalent " or

or  (course), especially

when the training is in a brand new sphere - such as banking

or finance - or is being provided by an international organization. (course), especially

when the training is in a brand new sphere - such as banking

or finance - or is being provided by an international organization.

In Azeri, there is now a distinction between "expert"

and "specialist". An Azerbaijani who has knowledge

and experience in banking, business, finance or another new sphere

is called a "specialist", whereas a similar person

from overseas is more likely to be known as an "expert".

The phrase "busy season" is widely used in foreign

companies and is now appearing in both Azeri and Russian conversations:

A busy season should start in a week.

During Soviet

times, a person who was applying for a job would submit a document

called a  (autobiography).

Today, this document is still used for job openings in local

State enterprises; however, for foreign companies and some local

private enterprises, candidates submit a different type of document

called a "CV" (curriculum vitae). The word "CV"

has been borrowed and is now used extensively in both Azeri and

Russian, much more so than the word "resume": (autobiography).

Today, this document is still used for job openings in local

State enterprises; however, for foreign companies and some local

private enterprises, candidates submit a different type of document

called a "CV" (curriculum vitae). The word "CV"

has been borrowed and is now used extensively in both Azeri and

Russian, much more so than the word "resume":

Send your CV by the 15th of the month.

Sometimes the

word "meeting" ( in Azeri, "sobraniye" in Russian) causes confusion.

Employees of foreign companies often use this word to mean "discussion"

or "session". But many other Azerbaijanis are not aware

of this meaning; they still think of "meeting" in the

sense of a "crowd gathering", as in a demonstration

or protest. This latter meaning was often invoked during the

first few years of the Popular Front movement a decade ago. As

a result, some Azerbaijanis might misunderstand sentences such

as:

in Azeri, "sobraniye" in Russian) causes confusion.

Employees of foreign companies often use this word to mean "discussion"

or "session". But many other Azerbaijanis are not aware

of this meaning; they still think of "meeting" in the

sense of a "crowd gathering", as in a demonstration

or protest. This latter meaning was often invoked during the

first few years of the Popular Front movement a decade ago. As

a result, some Azerbaijanis might misunderstand sentences such

as:

I'm going to a meeting now.

We have a meeting at 2 o'clock.

More English

English words are popping up more and more in short phrases or

replies, such as "OK", "great", "bye"

and "cool".

I'll be waiting for you at 10 o'clock in front of our house.

"Wow" is beginning to be used by Azerbaijanis as an

exclamation of surprise or amazement:

I finished the translation of the book in a month.

H:

Wow!

"Ouch"

is sometimes overheard around children, especially those who

are learning English or who have been exposed to cartoons and

children's movies in English.

"Oops" sometimes replaces  (Azeri)

or "oy" (Russian) in the speech of both Azeri-speaking

and Russian-speaking young people: (Azeri)

or "oy" (Russian) in the speech of both Azeri-speaking

and Russian-speaking young people:

Oops, I did it wrong.

"The Language"

Since independence, the phrase "the language"  (as opposed to "a language")

has come to refer to the prestige of knowing English. (as opposed to "a language")

has come to refer to the prestige of knowing English.

I want my children to learn the language well.

To work at this job, you should know the language.

In the past,

Russian was "the language". Today, however, Azerbaijani

parents are anxious to have their children learn English. Many

families seek private English teachers, even though lessons may

cost between $5 and $20 each. If a family can't afford this amount,

the parents try to find less-expensive language courses, hoping

that English will jump - start their children's future educational

and job opportunities. Even older Azerbaijanis are eager to learn

"the language", perhaps to find a better job or to

emigrate.

Focus on Azeri

The Azeri language itself is becoming more prominent in Azerbaijan

as well, a change that is even noticeable among very young children.

It used to be that a baby's first words were in Russian: "mama"

(mother) and "papa" (father). Now they tend to be in

Azeri:  (mother) and (mother) and  (father). The words for "grandma" (father). The words for "grandma"

and "grandpa" and "grandpa"

have always been

in Azeri. have always been

in Azeri.

As is true of children all over the world, Azerbaijani children,

even those barely able to speak, somehow intuit which language

to speak to which person. They have a knack for knowing how to

code-switch. For instance, they know if their grandmother prefers

to speak Azeri rather than Russian, and will proceed to talk

with her in Azeri though others in the family might prefer Russian.

Azerbaijanis, including those who are basically Russian speakers,

are now more likely to begin and end their conversations in Azeri,

even when leaving a message on an answering machine, technology

that has only recently been introduced to Azerbaijan. Since some

people still have difficulty carrying out the entire conversation

in Azeri (as they have been educated in Russian), they often

use Azeri to say "Hello, how are you?"  and then switch to Russian to carry on the main conversation

and then switch back to Azeri to say "Goodbye"

and then switch to Russian to carry on the main conversation

and then switch back to Azeri to say "Goodbye"

This tendency even occurs among the members of the popular Azerbaijani

rap group Dayirman (see article about Dayirman in this issue). They

sing and "rap" in Azeri at lightning speed, but they

communicate with one another in Russian because that's the language

in which they were educated.

We've observed that Turkish people who are living in Azerbaijan

are making a greater effort to speak Azeri. Immediately after

independence in 1991, when Turks first starting arriving in Baku,

the opposite situation occurred. Azerbaijanis would try to modify

their Azeri to accommodate the Turkish language. Today, the tendency

is reversed. Many people from Turkey try to adapt their intonation,

accent, word choice and even grammar in accordance with Azeri.

Some Turkish people have even begun to use Russian words that

Azerbaijanis commonly use. For instance, many hairdressers in

Baku are from Turkey. When they address their clients, they use

Russian words for terms like haircut (strizhka), hairdo (ukladka)

and bangs (cholka).

Another unofficial "trend" is the tendency of purifying

the Azeri language, which means replacing Persian, Arabic and

sometimes even European words with words of Turkic origin. Such

words are being introduced into the Azeri language mainly through

the media; some have taken considerable time to gain acceptance.

For instance, the word  (before) has replaced

(before) has replaced  ,

which comes through Persian. ,

which comes through Persian.  (last

name) has replaced (last

name) has replaced  , which

comes through Russian. Other examples include , which

comes through Russian. Other examples include  (cooperation),

which has replaced (cooperation),

which has replaced  , and , and

(number), which

has replaced (number), which

has replaced  . .

Less Formality

There has also been an effort to get rid of some of the language

patterns from the Soviet period. For instance, before independence,

everything belonging to Russia or the Soviet Union was referred

to as "ours", since almost all property was state-owned.

For example, an Azerbaijani watching a Russian movie would say

in either Azeri or Russian: "This is our movie." It

would be rare for an Azerbaijani to talk this way today.

Formal interactions are starting to be replaced by more personal,

informal ones. A decade ago, Azerbaijani graduate students would

have addressed their professors as "Dr. So-and-so".

It would have been considered rude to call the professors by

their first name. Today, with Azerbaijani students returning

from studying abroad in high school exchange programs, especially

in the United States, it's not so unusual for students to address

professors on a first-name basis.

TV announcers are also less formal and tend to interact with

the audience more, most noticeably by speaking in the first-person

singular - "I", rather than the editorial "we".

In the past, TV announcers tended to say sentences like, "We

would like to acquaint you with the program for tomorrow."

Today, there is a greater tendency to say: "I would like

to acquaint you" Journalists are also encouraged to express

their opinions more openly, since they no longer have to represent

Party policy.

Forms of Address

In English what do you call a person from Azerbaijan? At present,

there are at least three different ways: "Azeri", "Azerbaijani"

and "Azerbaijanian". In most cases, people in Azerbaijan

use "Azeri" to refer to a person and "Azerbaijani"

to refer to the language. Not many young people use "Azerbaijanian",

perhaps because it's so long and more difficult to pronounce.

However, each of the terms can refer to the person or the language.

When speaking to or about a woman, people in Azerbaijan are likely

to say  rather than rather than  , the older form. The word , the older form. The word  has always been used in Azeri

as a form of address to a woman, but it was not as widespread

as it appears to be today. The term is quite flexible and can

be used to refer to a young girl or an older woman, either married

or unmarried. It is usually combined with the woman's first name,

as in has always been used in Azeri

as a form of address to a woman, but it was not as widespread

as it appears to be today. The term is quite flexible and can

be used to refer to a young girl or an older woman, either married

or unmarried. It is usually combined with the woman's first name,

as in

During the Soviet

period, there was a greater tendency toward using the words  (teacher) or (teacher) or  (citizen). Informal words like "

(citizen). Informal words like " (sister) and

(sister) and  (aunt)

are still used quite frequently today to address a woman. (aunt)

are still used quite frequently today to address a woman.

The word  can also be used

alone when the name is not known. For instance, in addressing

a stranger, just like "ma'am" is in English. can also be used

alone when the name is not known. For instance, in addressing

a stranger, just like "ma'am" is in English.

Excuse me, ma'am, someone is calling you.

With the increased

usage of  , the word is also

beginning to be used in the narrative form: , the word is also

beginning to be used in the narrative form:

A lady told me this today.

Making Toasts

A crucial part of any Azerbaijani party, reception or dinner

is the series of toasts, given first to the honoree of the party,

then to the other guests. At these events, it seems that Azerbaijani

men have become bolder about complementing women when they address

or raise toasts to them. Expressions such as "this charming

lady"  or

"this beautiful lady" or

"this beautiful lady"  have become more common these days. In general, complimenting

women in public is not new, but it seems to be occurring more

frequently these days.

have become more common these days. In general, complimenting

women in public is not new, but it seems to be occurring more

frequently these days.

It's also common for toasts to refer to the Karabakh war, since

this is a topic that is on everybody's minds. Based on the recent

proposals from OSCE's Minsk Group for the resolution of the conflict,

many Azerbaijanis feel that the international community is putting

pressure on them to make the greatest compromise, not Armenians,

whom Azerbaijanis view as the aggressors in this war. Azerbaijani

toasts indicate that the general public is not willing to give

up Karabakh:

May we celebrate next year in Shusha [the major city in Karabakh,

considered the cultural heartbeat of the region].

I hope that next year this time we'll gather in Jidir Duzu/Isa

Bulaghi (famous places in Shusha) to celebrate.

Let's raise this toast to the liberation of Shusha/Karabakh.

I believe that this day will come.

Changes in Azeri

The Azeri language is dynamic, especially when it interacts with

other languages. As Azerbaijan undergoes social, political and

economic changes, its language will continue to be affected,

especially verbally. Some of these changes in verbal form will

eventually become new norms and standards for written Azeri.

Even though there is pressure on the Azeri language to "keep

up" with the new developments in the country, the Azeri

language is very rich and, therefore, does not need to invent

new words for all the new concepts that are being introduced

into Azerbaijan. For example, the word "scanner" is

borrowed because the concept behind it is new. But if a new word

appears for a concept that already exists, it seems irrelevant

not to use an existing word. The word "folder" (not

referring to a computer folder) doesn't have to be borrowed because

the Azeri language already has the word " ,

which can be used for the same purpose. ,

which can be used for the same purpose.

Changes in the Azeri language are to be expected; they make it

easier for Azerbaijanis to understand the rest of the world.

Fortunately, there seems to be little evidence that Azerbaijani

verbs are changing; they seem to be quite stable. The nouns are

showing the most modifications.

As in any language, verbs are the core of the system and carry

the greatest load in terms of maintaining its purity. If major

changes undermine the verb structures, the language itself could

be threatened. But that doesn't appear to be the case these days

at all with Azeri.

Jala Garibova has a doctorate in

linguistics and teaches at Western University in Baku. Betty

Blair is the Editor of Azerbaijan International. The entire

series of "Sociolinguistically Speaking" may be accessed

at AZERI.org.

______

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.1) Spring 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.1 (Spring

2001)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|