|

Spring 2001 (9.1)

Pages

20-24

Signals of Change

TV Debates

Between Azeris and Armenians

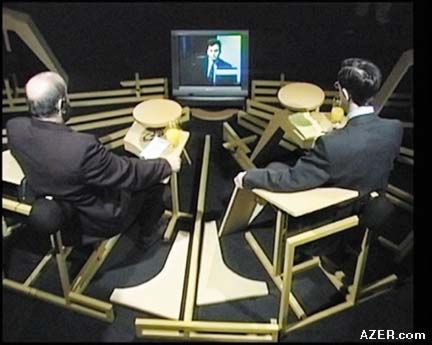

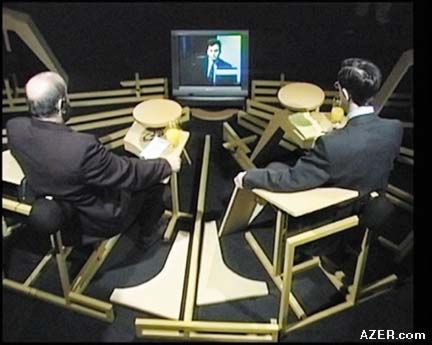

Photo: Taping of the TV program, Firing Line,

which aims to foster dialogue between Azerbaijanis and Armenians

about the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Inside the Azerbaijani studio

where Moderator Khayal Taghiyev (right) and guest view screen

with Armenian moderator Artyom Erkanian. The weekly program is

pre-taped and broadcast simultaneously in both Azerbaijan and

Armenia.

Back

in the 1980s when the Cold War was raging between the world's

two superpowers - the United States and the Soviet Union - an

experimental television program linked studio audiences via satellite

in both countries facilitating dialogue. Talk show hosts Phil

Donahue (U.S.) and Yuri Pozner (USSR) moderated the program.

The impact extended far beyond the two studio audiences as millions

of viewers in both countries began to see a human face on what

their own countries had portrayed as "the enemy". Consequently,

the program went a long way to ease tensions between two conflicting

powers.

The legacy of this daring experiment can still be felt today

in Azerbaijan and Armenia. The players have changed, but tensions

and distrust between the two countries, recently at war with

each other, is still high. The program called "Firing Line"

("Atash Khatti" in Azeri), is moderated by Khayal Taghiyev

and his counterpart in Armenia, Artyom Erkanian.

The program brings together experts - artists, politicians, economists

and others - from both sides to talk about issues related to

the Nagorno-Karabakh war. We asked Khayal to explain how the

program began and how it is fostering communication between the

two countries.

_____

The conflict that broke out in 1988 between neighboring Azerbaijan

and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh, a mountainous region inside

Azerbaijan of which the majority of the population is Armenian,

left thousands of military personnel as well as civilians dead.

A cease-fire was declared in May 1994, but the conflict is far

from over.

Left: Azerbaijani host Khayal Taghiyev. Photo:

Arzu Aghayeva. Left: Azerbaijani host Khayal Taghiyev. Photo:

Arzu Aghayeva.

Three

major issues have yet to be resolved: (1) the return of seven

districts located outside of Karabakh, which Armenians militarily

occupy, (2) the resettlement of nearly 1 million Azerbaijani

refugees back into these regions that are currently occupied

by Armenians, and (3) the status of Nagorno-Karabakh in relationship

to political rule.

Amidst this atmosphere of waiting and delays has come a breath

of fresh air - a TV program that links both sides in an ongoing

discussion. In each program, well-known experts from both countries

discuss issues related to Nagorno-Karabakh and the war. The program

is conducted in Russian, the language common to both countries,

which lived under Soviet domination from 1920 to 1991.

Left: Armenian host Artyom Erkanian. Left: Armenian host Artyom Erkanian.

In Azerbaijan, the program is broadcast by Azerbaijan News Service

(ANS), the Republic's most respected independent TV station;

in Armenia, it airs on Prometevs. Since its inception in October

2000, the show has aired simultaneously in both countries each

Thursday from 10-10:30 p.m. The program is pre-recorded in Mir

television studios in both Azerbaijan and Armenia. The funding

for the six-month, 24-program series comes from the U.S. government

via USAID, which funds Internews, the producer for the program.

Internews is an international non-profit organization that supports

open media worldwide. The company fosters independent media in

emerging democracies, produces innovative television and radio

programming and Internet content, and uses the media to reduce

conflict within and between countries.

According to a recent public opinion poll, the program had a

rating of 49 percent of ANS' potential viewers. "Personally,

I call the program 'Telebridge'," says Khayal Taghiyev,

Azeri host of the program. "But in my opinion, its official

name 'Firing Line' is exactly on target because at present, there

really is a firing line that is separating Azerbaijan and Armenia."

Even though the program is based upon a fairly simple concept,

it's the first show of its kind there. "As far as I know,

there have never been any TV programs like this in Azerbaijan,"

Khayal says. "There were several earlier attempts but all

were short-lived."

Photo: Azerbaijani Moderator

of Firing Line, Khayal Taghiyev (left), with Azerbaijani guest.

Photo: Arzu Aghayeva.

Khayal says that the public's reaction to the program has been

positive in both countries. You can overhear people discussing

the issues openly in public transport - in buses, taxis, the

Metro. "When we began this program, our goal was simply

to give people a chance to speak - to express their opinions.

As you can imagine, politicians are interested as well. They

want to know the opinions of the opposite side. Azerbaijani politicians

want to know what well-known Armenians are thinking and saying.

I've heard it's the same in Armenia."

Khayal's role is to help choose topics, select guests and moderate

the Azerbaijani side of the program. Guests must be fluent in

Russian and recognized as experts in their fields.

Tense Debate

Since Azerbaijan and Armenia have such a complicated relationship,

it's been difficult to reach a level of dialogue, especially

between the intellectuals and political elite from both sides.

No matter what topic is being discussed on the program, the two

sides usually start blaming and attacking each other. "I

doubt that we could find a single person in all of Azerbaijan

who would not be critical of the Armenian side," notes Khayal.

"How can I not be critical of Armenia?" he admits.

"These are the people who are occupying my country and have

forced hundreds of thousands of my fellow countrymen from their

homes and communities.

"Azerbaijan's viewpoint was shaped long ago," he continues.

"In Azerbaijan, people are convinced that Nagorno-Karabakh

is an integral part of our territory and that Armenia must give

us back the land that they are occupying. Such a position is

supported by four separate resolutions that were passed by the

United Nations in 1993 and 1994, which identify the Armenian

side as the aggressors in this war. The principle of 'territorial

integrity' was also supported by the OSCE (Organization for the

Security and Cooperation in Europe) at its Lisbon Summit in 1997.

The release of occupied territory is provided by international

law."

Photo:

Firing Line

Studio: inside the Armenian studio where Moderator Artyom Erkanian

(right) and guest view screen showing Azerbaijani moderator Khayal

Taghiyev.

Khayal describes how most program sessions develop. "Usually

our guests talk to each other on this level: 'Azerbaijan suffers

from this situation as a result of the war initiated by Armenia.

You are the side that started the war, you are the side that

thrust this war upon us.'

"But the Armenians counter by insisting that the people

living in Karabakh want to determine and rule themselves, and

that Azerbaijanis became aggressive toward them and organized

events like the 'pogroms' in Sumgayit. In my opinion, I think

that historical memory often impedes resolution on both sides."

Khayal admits that the hardest thing about moderating the program

is never knowing what to expect from his Armenian colleague.

"I never know ahead of time what the Armenian side is going

to say," Khayal confesses. "Sometimes they put me in

an awkward position. But I suppose there are times when I do

the same to them as well."

Even if the conversation flares up into an argument, nothing

is edited out. "From the beginning, the program organizers

decided not to cut anything, even though the program is pre-recorded

and aired later. The fact that it runs unedited creates a certain

tension that we like," he admits.

And yet, as long as both sides have the chance to speak to each

other, some form of dialogue is possible. "To tell you the

truth, before getting involved with this program, I thought it

was impossible for both sides to reach an agreement," Khayal

says. "I hope I'm not too courageous to think this way.

But I'm really convinced that it is possible to solve this conflict.

I hope this program will help convince people that the two sides

really can agree on certain principles.

"One thing that has emerged from our discussion is that

so far all of the guests have agreed that this problem must be

solved in a peaceful way," he continues. "It's just

that disagreements arise when we try to figure out how to do

that."

Controversial Topics

Each week "Firing Line" discusses a new topic related

to the war. They've discussed the negotiations process; compromises

that might be necessary to resolve the conflict; whether the

war might be rekindled and, if so, under what conditions; women

and conflict; the effects of the war on ecology; and even war

and cinema; social psychology, military personnel, transportation

and communications, and youth.

|

|

Photos: The conflict between

Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh erupted in war in

1988 with a very tenuous cease-fire signed in 1994. The conflict

has left tens of thousands dead and about 1.2 million refugees

displaced from their homes in both Azerbaijan and Armenia.

The program that aired February 15, 2001, for instance, dealt

with "Economy and Conflict." Heydar Babayev, chairman

of the Azerbaijani State Securities Committee, debated former

Armenian Speaker of Parliament Khosrov Arutyunyan. They discussed

the possible benefits of reestablishing economic ties between

the two countries, and whether such an action would promote a

political settlement to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Babayev stated

that although economic ties could definitely benefit Armenia

- for the present, they were out of the question while nearly

20 percent of Azerbaijan's territory remained under Armenian

occupation. Arutyunyan insisted that Azerbaijani goods were in

high demand among Armenian consumers, and that there was a lively

illegal border trade going on. He tried to show that Azerbaijan

needed Armenia as an economic partner with its more than 3 million

potential consumers.

Another topic that has been explored was the possibility of territory

exchange - an idea fostered by American Paul Goble of Radio Free

Europe in the early years when the conflict broke out. But both

sides flatly refuse such a possibility. Neither side agrees to

the possibility of giving Karabakh to Armenia in exchange for

giving Mehri to Azerbaijan. Mehri is the strip of land that separates

Nakhchivan (the noncontiguous part of Azerbaijan) from mainland

Azerbaijan.

But the major obstacle is that Mehri provides the direct link

between Iran and Armenia. Nor would Moscow, being a strategic

partner with both Armenia and Iran, approve of this idea.

On the other hand, Azerbaijanis associate Karabakh with the town

of Shusha and cultural heritage, homeland of mugham, music, poetry

- so there are immensely deep emotional ties. Such a land swap

or redrawing of borders might look feasible on paper, but it

doesn't work because of moral, economic and political implications.

In fact, according to Khayal this was one of the few topics that

both sides have agreed upon. Neither of them are willing to accept

a land swap as part of a peaceful resolution.

Jazz and War

"Firing Line" has also addressed topics of less political

import, such as the war's effects on jazz in both countries.

"The topic of jazz may seem strange," Khayal explains,

"but in Armenia and especially here in Azerbaijan, there

is a special sensitivity toward jazz. We decided to invite outstanding

jazz musicians from both Azerbaijan and Armenia to learn their

attitudes about the war.

"I appreciated Javan Zeynalli's [Azerbaijani jazz musician]

selflessness and civic courage when he could say: 'We are musicians,

we can't speak in the language of force and violence. Let's speak

in the language of jazz and music, the language that can bring

us closer to each other.'

"It was one of only three programs in which we didn't mention

the conflict at all," recalls Khayal. (The other two topics

were earthquakes and football.) "We only talked about music

and musicians. The Azeris wondered what had happened to some

of the famous Armenian musicians who had previously been living

in Baku. The participants talked about the current financial

crisis that musicians are facing. Nobody blamed the other side,

by saying: 'You occupied' or 'You didn't let us solve this problem

in a peaceful way.'"

On another occasion, the topic of "Rights and the Conflict"

came up with the ensuing discussion about the issues of territorial

integrity (Azerbaijan's position) vs. the right of national self-determination

(Armenia's position) and how these principles contradict each

other.

When it comes to the topic of religion, Khayal is convinced there

are two sides to this issue - propaganda and reality. Armenians

seem to have been able to convince Western media that this is

a religious conflict, pitting Armenian Christians against Azerbaijani

Muslims.

But Khayal insists that the war stems from other motivations.

"The reality is that both of our countries were governed

under the umbrella of the Soviet Union. All Soviet countries

were quite atheistic, as there was hardly any religious practice

being carried out. When the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia

broke out in the late 1980s, the Soviet Union was still in existence

and had not yet collapsed."

In other words, Khayal insists that the conflict has nothing

to do with religion. Instead, it was related to territorial pretensions.

Azerbaijanis believe the problem won't be solved until the true

motivation for the conflict is identified. For them, any propaganda

related to religious explanations does not contribute to solving

this problem.

First in his Field

Khayal Taghiyev has had what seems like a whirlwind career in

journalism. After studying at Baku State University, he began

writing for one of the first independent newspapers in Azerbaijan

in 1991, the year Azerbaijan gained its independence. In 1997,

Khayal was hired by ANS to work as a TV correspondent. The following

year, he started writing and editing for "Khabarchi"

(News) TV program. "ANS has always been close to my spirit,"

Khayal says, "even before I worked there, because it's really

an independent channel."

He never expected to be chosen to host "Firing Line".

It came as a surprise. Khayal has never traveled to Armenia,

though in the near future, he hopes he'll get to. He doesn't

know many Armenians personally, though he served in the Soviet

Army and developed a close friendship with an Armenian from Abhazia.

But when the opportunity presented itself to moderate the program,

he was thrilled. He loves new challenges. "I'm always in

search of something new. Such an assignment meant taking on a

great responsibility. People had to trust me to be able to carry

this off."

Actually, it was a daring experiment. "We didn't know how

people would respond. I think it's because they have so much

confidence in ANS TV that it really worked," says Khayal.

"The founders of ANS - the Mustafayev Brothers - Vahid and

Seyfulla, were very involved in the war. Their brother, Chingiz,

a TV journalist, was killed while on assignment near Agdam. [See

Azerbaijan International (AI 7.3), Autumn 1999].

Both moderators for the program are quite young. Khayal is 34

years old; his Armenian counterpart is only 30. "This is

what is happening all across the former Soviet Union.

Rejuvenation is taking place. It's a new period for us. And young

people are leading the way."

Khayal hosts two more TV shows. The first, called "Otan

Hafta" (Past Week), is an analysis of current events, a

show that he has hosted for the past two years. It airs each

Sunday at 9 p.m, and is followed at 11 p.m. by his talk show,

"Ahata Dairasi" (Field of Coverage).

Since this program appeared in April 2000, talk shows have become

very popular in Azerbaijan. "ANS started this tradition

in Azerbaijan," Khayal says. "Now there are many talk

shows on other channels as well."

In fact, the high ratings of "Ahata Dairasi" helped

Khayal garner the host position for "Firing Line,"

says Ilham Safarov, managing director of the Azerbaijani Representation

of Internews.

"We chose Khayal based on how he looked in front of the

camera, his intellectual prowess and his extensive television

experience." It seems the public endorses their decision.

At the end of 2000, a public opinion poll named Khayal 'Best

TV Journalist of 1999', with 'Ahata Dairasi', the most popular

TV program."

Future Programs

Khayal hopes to transform "Firing Line" into an even

more dynamic and interactive program. "The two moderators

would like to show a broader spectrum of viewpoints," he

says. "Right now we present only the viewpoints of one guest

from each side. We'd like to bring more guests into the studio,

and stimulate more complex discussions."

Another innovation for future programs is that the hosts have

decided not to make any comments of their own. "Before,

we used to interrupt our guests to make comments," Khayal

explains. "Now we see our task as only to ask questions

and guide the discussion, not to express our personal opinions.

We're there to keep the program on track and keep our guests

from deviating or straying from the topic."

The Bigger Picture

When asked about his personal views on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict,

Khayal says it's a problem that essentially must be solved between

the two countries themselves with the international community

providing guarantees for the safety of all peoples.

He sees the war as a legacy left over from the Soviet period.

"In Azerbaijan, people are convinced that there are geopolitical

forces that have certain interests in not resolving the problem,

especially when it comes to the Russian armed forces that have,

at times, supported one side, and then the other.

"Moreover, the leadership of the Communist Party and the

Politburo also played a certain role in exacerbating the problem.

The Communist ideology was based on the misconception that every

nation has the right of self-determination, but at the same time,

it denied individual human rights to all of its citizens.

"Let's suppose that there is a provisional state of Azerbaijan

within the USSR," he says. "The vast majority of the

population is Azerbaijani, but there is a certain enclave of

Armenians. What should be done? The genuine solution is to guarantee

that this minority be given all of the rights that Azerbaijanis

have, according to the rights granted by the Constitution. There

must be no difference between nationalities.

"But how did the Communists settle this problem? They separated

this enclave and created artificial borders, naming it Nagorno-Karabakh.

But the problem of self-government can't be solved like that,"

he insists. "In democratic countries, self-government is

not solved by creating borders, but rather by the Constitution

and the law. The Communists only created the appearance of self-government.

Then, when everything that the Communists built started to collapse,

Armenia stepped up and said: 'This territory belongs to us.'

"When we asked 'Why?' they replied, 'Because it has borders.'

"'We're sorry, but who created those borders?' we countered.

"And they balked: 'You can't guarantee the safety of our

people.'

"And again we countered: 'We inherited this problem.' Safety

is secured by giving civil rights.

The truth is that to a certain extent, every Azerbaijani in Baku

is also deprived of certain rights. This is a problem that has

carried over from the totalitarian regime.

"In my opinion, Azerbaijan must be one country that is divided

into various provinces, not according to nationality principles,

but territorial ones. Accordingly, relations with the territories

that have a certain status of self-government must be established

on a democratic basis."

Occupied Territories

Armenia must return all of the territories that it is occupying

- Kalbajar, Zangilan, Lachin, Gubadli, Aghdam, Fuzuli and Jabrayil,

along with a portion of the Tartar region - Khayal insists. "Only

after that happens will it be possible to start a dialogue on

the status of Karabakh. Once they give up their claim, we can

agree with those conditional borders, accept their rules and

say: 'This is our compromise.'

"As for a compromise before the release of those territories,

I see no sense in making one when so much of our territory is

still occupied." And as for the status that might be given

to Armenians living in Nagorno-Karbakh, Khayal thinks there are

too many problems to solve before such status is determined.

"If we could alleviate the difficult social conditions under

which our refugees are living, then our psychology would change.

The element of confrontation would be lessened." According

to Khayal, the difficulty is compounded when Armenians insist

that all of these problems must be resolved at the same time

- the refugee problem, the issue of occupied territories, the

status of Karabakh.

"No matter what you call it, the reality is that so many

problems can only be handled gradually - one by one. Nor can

the status be something that can be established in two or three

days. This is how I feel about it." Of course, the Armenians

have counter arguments, he admits.

Khayal believes that international guarantees will be important

in carrying out an eventual solution. "Let's say that we

start conducting negotiations on Karabakh and come to a certain

conclusion within a year. All this must be carried out within

the framework of international guarantees. This will provide

a certain kind of compensation. For example, if the two sides

don't trust each other, the guarantees may help to compensate

for that suspicion and mistrust."

Khayal says that above all, communication between the two sides

is crucial. "People need to communicate, regardless of their

nationality. If people don't speak to each other, then they start

shooting. I'm not a pacifist, I'm a journalist. And I consider

this problem from a professional point of view.

"The main thing is not to give people the grounds for total

disappointment, not to let them think that this problem has no

other solution than waging war. I realize that some of our territory

is occupied, and we must do our best to get it back. If there

is any ray of hope, any chance to remedy this situation, we must

reach out for it.

"We must show people that dialogue is possible, even in

difficult situations. Not everything has to be solved on the

battlefield. And yes, I'm optimistic. I do believe that we will

be able to overcome the difficulties that hinder and impede us

now. But it will take time."

Khayal Taghiyev was

interviewed by Editor Betty Blair and Editorial Assistant

Arzu Aghayeva. Assistant Editor Jean Patterson

also contributed significantly to this article.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.1) Spring 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.1 (Spring 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|