|

Summer 2001 (9.2)

Petroleum Section

Progress

on the Main Export Pipeline

Interview with David

Woodward

Associate President, BP Azerbaijan

by Betty Blair

It seems like everybody

in Baku is hanging around waiting for the pipeline route to be

decided upon and, of course, ultimately built. What's happening

these days? What stage is the process at right now? It seems like everybody

in Baku is hanging around waiting for the pipeline route to be

decided upon and, of course, ultimately built. What's happening

these days? What stage is the process at right now?

We have made a lot of progress on the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC)

[spelled through Turkish, but pronounced Jeyhan in English] pipeline

this last year. We have now concluded the three HGAs (Host Government

Agreements) with Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan. In 1999, we

had finished the agreement with Turkey. Then it took us quite

a while to carry out extensive negotiations with Georgia covering

the environmental standards, security issues and commercial terms

of the pipeline construction through that country. We signed

with them during the second quarter of 2000. Then we were able

to quickly finalize the HGA with Azerbaijan.

Subsequently, we had to establish a group of companies that were

ready to get involved with the first stage of the project - the

Basic Engineering stage. At that time, we got agreement from

six other AIOC partners (Statoil, Unocal, TPAO, ITOCHU, Delta

Hess and Ramco) to join BP and SOCAR in what we call a "Sponsor

Group" to undertake the initial stages of the project.

Discussions with other companies, including Chevron and Total

Fina Elf, continue to see whether they would be interested in

joining the Sponsor Group, or perhaps be prepared to ship their

oil volumes through the pipeline rather than be investors in

it. We are interested in both types of cooperation - investors

and shippers of oil.

We signed an agreement forming the Sponsor Group with SOCAR (State

Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic) and the HGAs with the host

governments on October 16, 2000.

It was really quite a significant milestone, I must say, after

so many years of discussions. It signified that we were ready

to spend serious sums of money on Basic Engineering, develop

the legal and commercial aspects of the pipeline company that

we expect will be formed, and start looking at how to secure

external financing for the project.

After this work finishes towards the end of May 2001, we have

a month in which to decide whether to proceed to the next stage

- Detailed Engineering - which would take 12 months to complete.

In that stage, we would complete the engineering design of the

pipeline, pump stations, terminals and so on and invite tenders

for the supply of materials and equipment, and construction services.

When will the exact route be determined?

We're selecting the route right now during the Basic Engineering

phase. This process involves looking at the environmental impact

as well as the social impact of the pipeline, to determine how

it might affect communities along the pipeline route. We also

have to consider if the areas where we want to lay the pipeline

are safe and if the facilities can be protected.

Above: Proposed timeline for

the planning and construction of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC)

pipeline.

What's involved when you consider the environmental impact of

the pipeline?

We undertake what we call an Environmental Impact Assessment

(EIA) as well as a Social Impact Assessment (SIA). Clearly we

want to avoid particularly sensitive areas - regions of outstanding

natural beauty or areas where construction activity or any potential

oil leak at any stage of the operation would have an unacceptable

impact on the environment. We are obviously looking at where

there are aquifers of drinking water and making sure that construction

activity is well clear of those areas.

We do a tremendous amount of consulting with government agencies,

non-governmental agencies and the public to learn about their

concerns. Ultimately, we have to gain approval from the government

as to the exact route of the pipeline, and we have to indicate

which criteria we have used to decide upon that specific route.

The government then consults with its own experts for advice

about any sensitivity in particular areas.

And the Social Impact Assessment?

We have to be concerned about the impact of the pipeline, particularly

in populated areas. We want to minimize the need to move people's

houses and we want to avoid disrupting farming activities as

well, not just when we are operating the line, but also when

we are constructing it, especially since we have to move in materials,

all of the pipe and other equipment.

Thousands of truck loads of equipment will need to be brought

in, so we have to consider which roads to use so we don't present

a hazard for any particular community. In situations where we

do anticipate difficulties, we have to ask ourselves if there

is any way we can avoid these by choosing a different route.

Above: Much of the proposed

pipeline will use 42-inch diameter pipes.

At this stage we are looking at a corridor of land 500m wide.

Eventually, we'll narrow this down to a few tens of meters to

determine exactly where to dig the trench. At that point we'll

begin more detailed discussions with the communities on the environmental

and social impact of the project and determine what can be done

to minimize difficulties.

The Social Impact Assessment looks at the micro-level issues,

which involve local communities, as well as the macro-level issues

in countries such as Azerbaijan or Georgia. We try to anticipate

how much the oil economy will impact the country once revenues

start to flow. We are concerned about how these countries are

going to use oil revenues to benefit the people.

Of course, the host governments themselves make the ultimate

decisions about using those revenues. But we need to communicate

with them about these issues and make sure that they understand

the size and timing of oil revenues so they can start thinking

well in advance about how they are going to manage the impact

they will have on the economy.

Let me ask you a few more questions about the pipeline itself.

For example, how are you planning for the security of the pipeline?

Firstly, in each country, there are physical locations within

their territory that the respective governments use for military

manoeuvres and exercises. We will identify those areas and avoid

them.

We also have to consider how to protect our staff and facilities

from any sort of attack. The concern is not so much about bombs,

as that would clearly be an act of war, but rather about terrorist

or criminal activity, especially cases where people might try

to break into some of these facilities. For example, if people

felt they were not receiving the benefits they expected from

oil activity in the area, they might decide to take action against

the pipeline or the companies involved with it.

So we have to consider security arrangements, such as fencing

and other forms of physical protection, and security systems

that detect intruders and prevent illegal tapping of the pipeline.

Many of the lines in the region have been tapped to take off

a stream of oil. So it may not always be a case of sabotage,

but people taking advantage of the situation for financial gain.

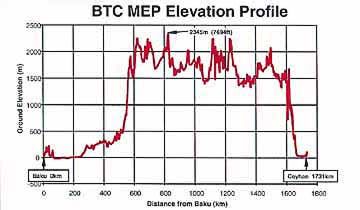

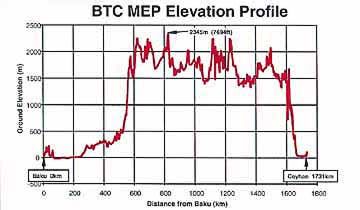

Left:

The proposed

Baku-Tbilisi

-Ceyhan pipeline would vary in elevation from sea level to close

to 2,500 meters. The ascent begins in Georgia and continues through

the mountains of Turkey before its descent near the Mediterranean

seaport of Ceyhan.

What about earthquakes, since the region is known to have them

occasionally?

The pipeline will be designed to withstand the intensity of any

earthquake that one might expect to encounter in this region.

This sounds like a huge project. Have you personally been

involved at this level in assignments that you've held before

in other countries?

I think I've done most of the things that we need to do or will

encounter as part of this project, although perhaps not all at

the same time. I've been responsible for major operations before,

for example, onshore in Abu Dhabi.

It's exciting, isn't it, to be on the cutting edge of the

new oil development in Azerbaijan?

I think it's a tremendous privilege to be able to manage projects

of this magnitude, to live and work in this place at this stage

in its development, where the activities that we're engaged in

mean so much to the country. We contribute to the country's development

in terms of helping establish economic independence and national

identity. I thoroughly enjoy working with the people here and

have very high hopes for their future.

It seemed like when you first came here two years ago, BP

was not so set on this idea of the Ceyhan pipeline. Is that right?

That's probably a fair assessment and probably reflects the attitude

that most companies held. There were still very significant hurdles

to overcome. We had not been able to negotiate agreements with

all the transit countries, and we knew that would require a major

effort.

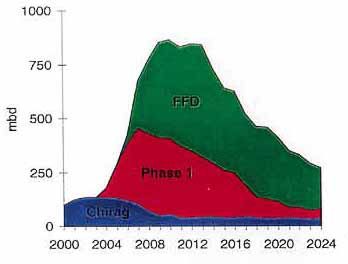

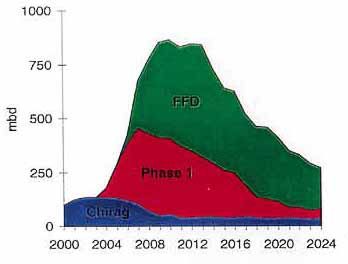

Right: Projections of oil that

will be produced in Azerbaijan in the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli project Right: Projections of oil that

will be produced in Azerbaijan in the Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli project

Many countries that produce oil have the luxury of having direct

access to international ports. Sometimes there is one adjacent

country that they have to pass through, so some bilateral negotiation

has to take place. But having three countries along a route is

quite unusual.

Our first negotiations were with Turkey. It's understandable

that we would start in that country given that two-thirds of

the pipeline will transit Turkey, and that the export terminal

will be at Turkey's Mediterranean port of Ceyhan.

The full length of the planned pipeline is about 1,750 kilometers

(1,100 miles), and it passes over mountains in Turkey that are

more than 8,000 feet high.

Actually, Azerbaijan is the easy part of the route because it

has flat terrain. The pipeline would then begin the climb up

into the mountains in Georgia. These heights are not too difficult

or challenging. But then as the pipeline approaches the Turkish

border, it begins to climb some serious mountains. Through most

of Turkey, the pipeline is up in the mountains until it nears

the Mediterranean, where it heads down to the coastal plain.

The ascent requires a number of pump stations to push the oil

uphill. Then on the descent you need pressure reduction stations

to make sure that the oil doesn't accelerate too fast downhill.

How large will the pipes be?

Above:

Map of the

proposed pipeline route from Baku, and Tbilisi, Georgia, and

on to the Mediterranean port of Ceyhan, Turkey.

That

has yet to be finalized. A considerable amount of it will be

42-inch diameter, which is what is required to facilitate the

pipeline at the million-barrel-a-day capacity that we're designing

it for. But some sections may have a larger diameter and it's

possible that in the downhill sections, it might be slightly

smaller, to slow the oil down.

We always knew that the Turkish section of the pipeline would

be the most expensive, and the Turks have stated that they can

build this line for a particular cost. As part of the negotiations

with them, we were able to conclude what is termed a "lump

sum turnkey contract". BOTASH, the State Pipeline Company

of Turkey, will construct the Turkish portion of the pipeline

to the agreed specifications for a cost of $1.4 billion. And

the Turkish government has provided guarantees that if the actual

costs were to exceed that amount, they will cover them.

That agreement took a long time to negotiate because we had to

be absolutely clear about what we were going to get for that

$1.4 billion, and that the Turkish section would be built according

to the environmental, safety and technical standards that we

require for the entire pipeline.

How do the transit fees vary from country to country?

In Turkey the transit fee, obviously, is higher than it is for

the Georgian section, which again is different from what it will

be in the Azerbaijan sector. In Turkey, the fee actually covers

both the transit fee and the operating cost, because BOTASH will

operate the pipeline on Turkey's behalf.

In Georgia and Azerbaijan, we - or whoever the participants appoint

as the operator of the pipeline - will have to cover the cost

of that operation ourselves, but still pay a transit fee to the

host government.

The next stage of the project is Detailed Engineering, which

requires us to make arrangements for land acquisition in Georgia

and Azerbaijan. In Turkey, as part of the lump sum arrangement,

BOTASH will buy the land, so we get the land as part of the deal.

In Georgia, the land is privately owned, and we will have to

negotiate with many individual landowners. The Georgian government

has committed to assist us in this process.

In Azerbaijan, much of the land is still public property, so

it's relatively easy for us to make an arrangement with the State.

Hopefully, we can agree to standard terms for costs per square

meter, perhaps with some range depending on the desirability

of the site. If we had to get into individual negotiations with

thousands of landowners, each would see this as an opportunity

to make some money, and we would never be able to finish the

process.

The Detailed Engineering phase will be completed by June 2002,

is that right?

Yes, and by that time we will have received and assessed bids

to determine who should receive each particular contract to supply

the materials, equipment and services. It's only at that point

that we will know exactly how much the pipeline will cost. The

Turkish section we know about, because it is guaranteed.

Is there any chance that you could you complete the Detailed

Engineering phase in 2002 and then abandon this route altogether,

thinking that it was altogether too expensive to take any further?

By the end of Detailed Engineering, we'll have a very firm cost

estimate for the construction project, we'll have firm contractual

commitments for volumes of oil to be transported through the

line and we'll know what external financing is available. There

is such a possibility, especially if we find that the costs have

escalated beyond our original estimates. Or it might be that

we still didn't have the required volumes of oil dedicated to

the line. Or it could happen if the bank said, "Sorry, but

this project doesn't look good enough for us to advance the funds."

The summer of 2002 is actually like a 'D-day' for this project.

At that time we could decide that we need more time to get others

to come on board with us. To complicate matters, many of the

bids for the project have expiration dates on them. For example,

a company might say that it can provide pipe, pumps and other

equipment, but that the bid is only valid for three months.

A company can't keep its bid open indefinitely without a commitment

from us. If they have this major contract just hanging out there,

they won't be able to continue doing business with others. And

if they don't see the whole thing moving ahead, then they're

not going to leave those offers on the table. So at that decisive

point, there is not going to be a lot of time before we have

to make a decision. Otherwise the whole thing starts to unravel.

How many different companies are likely to be involved in

building the pipeline?

It will be organized as a hierarchy, with one or two major contractors

that are responsible for the engineering design. Then we'll probably

have one managing contractor working with us.

Beneath that, there might be dozens of equipment suppliers, but

a lead contractor on the pump stations, for example, that purchases

valves, pumps and electronic equipment from dozens or even hundreds

of suppliers.

When we enter the Construction phase, we will only have one or

two lead construction contractors. They have subcontractors with

particular expertise in installing certain sorts of equipment.

Ultimately there could be hundreds of subcontractors and contractors

involved. But the operating company won't have to deal directly

with them.

As of right now, how much do you expect the pipeline will

cost?

The current estimate is $2.7 billion. That's $1.4 billion for

the Turkish section and $1.3 billion for Georgia and Azerbaijan,

including land purchase, but this is only what we call an order

of magnitude estimate.

The $2.7 billion figure is just for the pipeline. It doesn't

cover the costs of developing the upstream.

I'm referring to the Azeri-Chirag-deepwater Gunashli (ACG) field

that BP operates - the one covered by what is often referred

to as "The Contract of the Century". We expect to spend

another $12 billion or so on developing ACG to produce the oil

that would flow through the pipeline. That is the approximate

total amount needed for the platforms, wells and subsea pipelines

and for the terminal that we will build onshore.

To evaluate the investment before we embark upon a project like

this, we have to assess what the oil price might be over a very

long period, because these projects will span 20 or 30 years.

We have to have confidence that our cost estimate is quite on

target, that we have a fairly accurate estimate of the amount

of oil that can be recovered from the reservoir, and what the

production profile will be.

A lot of technical and commercial assurance work has to be done

before we actually embark upon a project of this magnitude. I

think that is one of the key differences between the way we do

business and the way the Soviet Union used to do business. We

are much more careful in advance of undertaking a major decision

such as this.

So you don't have to abandon it halfway through.

That would be the worst possible outcome - spending considerable

sums of money but getting nothing at all in return.

What other options do you have if the pipeline wouldn't work

out?

If we didn't develop the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan route, then we would

try to go to Supsa on Georgia's Black Sea coast, but that would

result in increasing traffic through the already crowded Turkish

straits. The throughput of CPC (Caspian Pipeline Company), going

through Novorossiysk (Russia), will be increasing over the coming

years. So there will be increasing volumes already routed through

the Black Sea and the Turkish Straits.

It's a "first-come, first-served" situation as to the

available capacity and the ability to use the Turkish Straits.

If we were to add more volumes in addition to that, it might

be the "straw that breaks the camel's back". I think

many people recognize that as CPC and other Russian exports increase,

a bypass around the Turkish Straits will be necessary in the

next decade or so.

What's the earliest the pipeline could be ready?

Early 2005. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan route will take approximately

32 months to construct. But we are saying that we really need

it by 2004. There's a reasonable chance that it could be speeded

up, particularly in the Construction phase. Perhaps it could

be completed by the end of 2004.

Let's talk about the new well that BP is beginning to drill.

What are you expecting to encounter in the Inam well?

We think it has a very good possibility of containing substantial

volumes of good-quality oil.

What makes you think that might be the case?

We do what's called Basin-Modeling work. We find out where the

hydrocarbons are generated in the basin and then how they have

subsequently flowed from the source rock into these reservoirs

and traps. As more wells are drilled, we have a better understanding

of what that process was.

As each well is drilled, you can test and refine your model.

There's the possibility that Inam could contain gas because we

have a limited amount of data upon which to base our model, but

we still think it is highly likely that Inam has oil rather than

gas.

But gas would be good for you, too?

Gas is good as well. Of course, it's possible that Inam has nothing

at all. That's why we drill wells. You can never guarantee what

is down there until you actually drill and penetrate the reservoir

horizons. We have very sophisticated techniques for giving us

a good idea of what's there, but we don't know for certain until

we go down and test.

Let's turn to U.S. politics and discuss the new Administration

in relationship to Azerbaijan's oil. U.S. President George W.

Bush and Vice-President Richard Cheney both have oil backgrounds.

Do you anticipate any change in the U.S. government's policy

in response to Azerbaijan?

I think people might have been misled into thinking that the

Ceyhan route was a U.S.-inspired project, that the U.S. has been

putting substantial resources into it and that the oil companies

are supporting it because they have had their arms twisted by

the U.S. This is not the case. We are moving ahead with this

project because we think it is good business. We think it will

provide us with the most commercially competitive means of exporting

oil from the Southern Caspian to international markets, while

avoiding the Turkish Straits and the environmental issues which

that poses. And that is clearly what the host government here

desires as well.

It's good to have the support of the European Union, and particularly

of the United States, but that is not what is driving this project.

If there were to be a change in the level of U.S. interest or

commitment, I don't think that would be critical to this project.

However, we hope the U.S. will continue to support it. I think

that what we are doing will help secure independence and the

development of democracy in the region.

If the U.S. adopted a different policy toward Iran and allowed

U.S. companies to trade with Iran, would that affect your plans

for the direction of the route of the pipeline?

I don't believe it would. I think it will be quite some time

before Iran's relationship with the West changes substantially.

Even if Iran were open for business today, we would still move

ahead with the Ceyhan route because we believe that this is the

most commercially competitive option available to us.

To start the lengthy negotiations process with Iran, which hasn't

actually done business with international organizations for many

years, and to secure the level of confidence that we would need

in order to make multi-billion dollar investments in that country

would clearly take time.

And we don't have that much time. We're moving ahead with our

Phase 1 Development of the ACG, and we have to have a means of

exporting the oil by the end of 2004.

Of course, we do hope that the relationship with Iran will change.

There are still huge oil and gas resources there, and we would

want to do business with Iran once it becomes possible to do

so.

I think that if the BTC were to be built and if the Caspian volumes

justified it, then one could imagine oil and gas being exported

into Iran. Multiple outlets are always more desirable than relying

on just one route.

When you look at what was known as the Silk Route on old maps,

you realize that there were really many silk routes just like

there are many pipeline proposals and routes today. What about

the oil that's coming from Kazakhstan? Is Azerbaijan likely to

be part of that formula?

I think it is certainly one of the possibilities. A significant

part of Kazakhstan's oil will go via CPC to Russian ports, but

with the potential that they see, they will almost certainly

need another means of export. So they are evaluating options.

I think one of them is south through Iran, and then another one

is across the Caspian into BTC. We've been in discussion with

the Kazakhstan government and with oil companies operating in

Kazakhstan, and certainly some of those have expressed real interest

in participating in BTC.

You've been here in Azerbaijan for more than two years now.

I'm wondering how your attitude about working with Azerbaijanis

has changed since you've got to know the people and country better.

It is striking to me how Azerbaijanis maintain a positive attitude,

despite the difficulties that they face. When I was in Russia,

there was much more of an air of gloom and despondency. I can't

help but admire the way that Azerbaijanis have coped with their

difficulties and with the progress that they have made in terms

of change and reform and their optimism for the future.

As far as the people are concerned, I find them very capable

and very pleasant to work with. That's one of the added bonuses

that comes with being assigned here.

David Woodward

was

interviewed in Azerbaijan International on a previous occasion;

see "At

the Turn of the 21st Century with AIOC President David Woodward," Winter 1999 issue (AI

7.4).

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.2) Summer 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.2 (Summer 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|