|

Autumn 2001 (9.3)

Pages

20-30

Another Wind

Memories

of the Birth of a Nation - Azerbaijan

by

Paolo Lembo

Related Articles:

(1) Lest

We Forget: The UN in Iraq - Sergio Vierira de Mello - Paolo Lembo

(2) Diplomatic

Interview with Paolo Lembo - Interview by Betty Blair

(3) Letter

from Kosovo - Paolo Lembo

(4) Infinitesimally

Short (Why Are We Killing Each Other?) - Paolo Lembo

Azerbaijan holds a special

place in the heart of Paolo Lembo, former United Nations Resident

Coordinator to the country. In 1992, shortly after Azerbaijan

became independent, the Italian-born Lembo became the first UN

staff member posted there. At 34, he became the UN's youngest-ever

UNDP [United Nations Development Program] Head of Mission. After

leaving Baku in 1997, Lembo was assigned to Tajikistan (1997-1999),

then Kosovo (1999-2001). He began writing these vivid memoirs

for us this past summer from an Internet cafe in Paris while

preparing for French language exams in anticipation of his new

responsibilities as UN Resident Coordinator in Algeria. We think

it's a rare glimpse of Azerbaijan in the early years of its nationhood,

written by a diplomat who developed a real passion for the country. Azerbaijan holds a special

place in the heart of Paolo Lembo, former United Nations Resident

Coordinator to the country. In 1992, shortly after Azerbaijan

became independent, the Italian-born Lembo became the first UN

staff member posted there. At 34, he became the UN's youngest-ever

UNDP [United Nations Development Program] Head of Mission. After

leaving Baku in 1997, Lembo was assigned to Tajikistan (1997-1999),

then Kosovo (1999-2001). He began writing these vivid memoirs

for us this past summer from an Internet cafe in Paris while

preparing for French language exams in anticipation of his new

responsibilities as UN Resident Coordinator in Algeria. We think

it's a rare glimpse of Azerbaijan in the early years of its nationhood,

written by a diplomat who developed a real passion for the country.

I have

always believed that the UN should be impartial, but never neutral.

We, the UN, must have the courage to stand up for the losers

and the forgotten. We must take sides when there is just cause.

If the UN doesn't do it, then who will?

"There's a message for you. The boss wants you to go to

New York. It's urgent."

It was a hot evening in July 1992. I was at the Headquarters

of the United Nations office for Afghanistan, in the city of

Termez on the border with the Republic of Uzbekistan. I knew

what the message was about.

Left: Paolo Lembo, UNDP Representative in

Baku, meeting with Azeri journalists on the occasion of the Inauguration

of the Reconstruction Program in Horadiz, in southwest Azerbaijan,

on October 24, 1996. A few refugees have returned to Horadiz

and are currently trying to eke out a living there. Most of Azerbaijan's

hundreds of thousands of refugees have not been able to return

to their villages and towns in Karabakh and the surrounding regions,

which have been occupied by Armenian forces since 1992 and 1993. Left: Paolo Lembo, UNDP Representative in

Baku, meeting with Azeri journalists on the occasion of the Inauguration

of the Reconstruction Program in Horadiz, in southwest Azerbaijan,

on October 24, 1996. A few refugees have returned to Horadiz

and are currently trying to eke out a living there. Most of Azerbaijan's

hundreds of thousands of refugees have not been able to return

to their villages and towns in Karabakh and the surrounding regions,

which have been occupied by Armenian forces since 1992 and 1993.

A few

months earlier (December 1991), the Soviet Union had collapsed,

leaving in its wake 15 independent republics. In a surprise move,

UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali had gained approval

from the UN General Assembly to open 15 new UN offices within

a record time of six months. Given the very tight deadline and

the insufficient resources put at the disposal of the UN for

such a task, it was to become one of the most formidable and

exacting operations ever undertaken by the organization.

As Chief of Mission for Afghanistan for the previous two years,

I was one of the few at the UN who were authorized to travel

in the region and knew the political geography of the republics.

I knew that one day there would be a telephone call for me. A

task force was being set up in New York City to open these new

offices, and I was being tapped as a Special Assignment Officer.

Two days later I was in New York. The Director was particularly

worried about a region that was becoming explosive - the Caucasus.

"I'd like you to leave immediately for that countrywhat

do you call it? I can never pronounce its name right - 'Abistrakhan'"

"Azerbaijan," I added graciously.

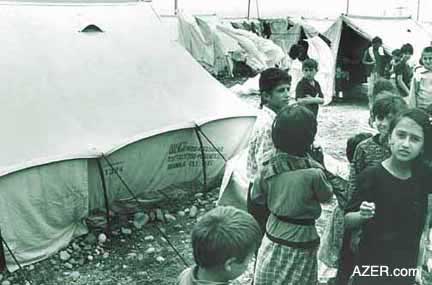

Left: Totally uprooted and exhausted, Azerbaijani

refugees of the Karabakh war fled the advancing Armenian troops.

Nearly 1 million Azerbaijanis were uprooted because of the war.

The lucky ones were able to bring out their belongings. Many

fled for their lives with only a few moments' notice. Photo:

Oleg Litvin, 1993. Left: Totally uprooted and exhausted, Azerbaijani

refugees of the Karabakh war fled the advancing Armenian troops.

Nearly 1 million Azerbaijanis were uprooted because of the war.

The lucky ones were able to bring out their belongings. Many

fled for their lives with only a few moments' notice. Photo:

Oleg Litvin, 1993.

"Right.

The Secretary-General is concerned and wants to open an office

there immediately. We have to move fast. I'd like you to leave

next Monday and try to sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)

with the government, for operations to begin in October at the

latest. You have two weeks."

His tone did not leave much room for discussion, so I started

to organize immediately. On August 2nd, the first UN mission

to Azerbaijan landed in Baku, with the goal of establishing an

operation there.

When we landed on the tarmac, two gentlemen from the Foreign

Office were waiting for us. Shamil was from the Department of

Foreign Office Economic Relations and was there primarily because

he spoke English fluently. He had been working with the UN during

the Soviet period and knew the organization and the international

scene very well. I was impressed with him, especially once I

realized that he was one of the few individuals in the government

who could speak English. Courteous and well read, he soon became

a much-loved and constant presence at the UN.

With him was another individual, a rather funny-looking, round-shaped

young man from protocol. He had an enviable, but incomprehensible,

self-consciousness and a certain flair for incessantly asking

unnecessary questions, mostly related to the possible benefits

and privileges that the Ministry staff could derive from a UN

project.

It seemed to me that this unique pair represented the two souls

of Azerbaijan. They revealed the contradictory, yet fascinating

culture of the country: the cosmopolitan, open, modern and dynamic

face along with the mercantile, opportunistic face.

The mission went very well. I discovered a wonderful country

and developed an immediate sympathy for it. Other members of

the mission had a different perception, probably because it was

the first time that they had traveled in the former Soviet Union.

They were shocked at how highly dilapidated the infrastructure

was. But this was typical of all Soviet republics. For me, the

Caspian Sea, Baku's bay, the passion, emotion, art, confusion

and, to a degree, the chaos, had a certain Mediterranean flair

and seductive power.

Left: The first Azerbaijan Human Development

Report was sponsored by UNDP (United Nations' Development Program)

in 1995 under the direction of Paolo Lembo. Subsequent reports

have been published in 1996, 1998, 1999 and 2000. Left: The first Azerbaijan Human Development

Report was sponsored by UNDP (United Nations' Development Program)

in 1995 under the direction of Paolo Lembo. Subsequent reports

have been published in 1996, 1998, 1999 and 2000.

Certainly,

the general atmosphere was grim, but what could one expect of

a country in the midst of three major transitions? Azerbaijan

was dealing with a war, a transition to a market economy and,

more specifically, the transition to democratic statehood.

Our team had the impression that we were the only foreigners

in the country. In the rare walking tours that we took around

the city, we felt like people were staring at us as if we were

extraterrestrials. The truth is, to a certain degree, we were.

Traffic was sporadic and very orderly; not a single foreign vehicle

was in the streets. No shops sold foreign goods. The people were

dressed in a rather uniform and gray style, a fashion that can

best be described as "Soviet". It was the same as what

you would find in every other former Soviet republic. But there

was also something different, something that I couldn't define

- a glimmer of

light that the darkness of the time could not completely extinguish.

Our first meeting with government officials confirmed the extreme

difficulty of the young republic's situation. The economy was

in shambles, military hostilities with Armenia were flaring up

in several border zones and the new democratic institutions were

very fragile. After taking into account the external influences,

the overall picture caused us grave concern.

Our meeting confirmed my worries. We discovered Foreign Minister

Tofig Gasimov, a scientist, to be a gentleman, an honest person

and someone truly devoted to his mission.

Above:

The United

Nations and numerous other humanitarian organizations provided

survival essentials of food and shelter for tens of thousands

of Azerbaijani families who fled their homes and villages in

the Karabakh and the neighboring regions when Armenian military

forces invaded Azerbaijan's territory [1992-94],. Azerbaijan's

refugees -

nearly 10 years later - still yearn to return home. Photo: Refugee

camp near Yevlakh. by R. Redmond, UNHCR, 1994.

"Mr. Minister, what are your primary concerns at this point

in time?" I asked.

"Everything," answered the Minister.

"Is there any specific sector you would like us to focus

on immediately?"

"Every sector."

I realized that to get at any answer, I would have to take a

different approach.

"Mr. Minister," I began again, "Do you have any

particular question for us on our future cooperation?"

"Yes, I do. When do you start?"

Left: Paolo Lembo (right) with Abid Sharifov,

who was in charge of organizing the Horadiz Reconstruction project

in 1996. Today Sharifov continues in his position as Deputy Prime

Minister. Photo: Blair, 1996. Left: Paolo Lembo (right) with Abid Sharifov,

who was in charge of organizing the Horadiz Reconstruction project

in 1996. Today Sharifov continues in his position as Deputy Prime

Minister. Photo: Blair, 1996.

decided to meet as many ministers as possible to shape our first

general Memorandum of Understanding. I realized we had a considerable

amount of work to do.

I'll never forget the first day of our arrival when I asked the

hotel to place a telephone call to New York. I was impressed

when the desk officer answered that this would be no problem.

"Not bad," I thought, "at least we have connections."

"I'm not in a hurry," I told him. "After 8 p.m.

will be fine."

"Which day?" the receptionist asked.

The following day, during a discussion with one of the ministers,

I mentioned this episode and stressed the importance of telecommunications.

I asked him if there were any electronic mail system in the Republic.

"We're much more advanced than that," he replied. "Of

course we have mail! We also have Telex, and soon we'll be getting

fax."

We worked day and night to finalize the text of the Memorandum.

I met several young, motivated economists and the staff of the

new administration, and soon realized the Republic's enormous

potential. The human capital was remarkable. The issue was just

how to make my colleagues at the UN in New York understand that

Azerbaijan was not a typical developing country. Its infrastructures,

both social and physical, were very well developed and the labor

force was highly qualified. The primary challenge at the UN would

be to figure out how to promote a process of transformation.

Photo: Interior of Baku's

ornate Opera and Ballet Theater, view from the stage. Courtesy:

UNDP.

In the meantime, the dark clouds of war cast a huge question

mark over any project that we attempted to define.

On August 16th, Foreign Minister Tofig Gasimov and I signed the

first Memorandum of Understanding that would lead to the establishment

of the UN Mission in Azerbaijan and the launching of the first

operations there in October 1992.

The ceremony was very emotional. In front of the cameras and

the press, all the journalists and the notables applauded and

the Minister smiled. But his smile could not hide his deep concern.

On my return to New York, I held a debriefing for a group of

senior UN officials. At the end, they all shared their concerns.

The situation in the Caucasus did not augur well. Of particular

concern was the deteriorating relationship between Azerbaijan

and Armenia. It was suddenly decided that Azerbaijan would be

the first office to open and that I would be assigned as its

first UNDP Representative. I had just turned 34, making me the

youngest Head of Mission in the organization ever.

I was surprised by the sudden turn of affairs. After all, I had

intended to return to Afghanistan after my special assignment.

Naturally, I was also concerned about the daunting challenges

of my new assignment in Baku. I never quite found out how my

appointment had been finalized. Most probably, it was a question

of practicality: there simply weren't that many Western officials

with knowledge about that part of the world or previous conflict

experience. In the end, I concluded that my appointment was a

matter of accidental circumstances.

Arriving in Baku

On October 25, 1992, I left New York for Baku. Inside my suitcase,

I carried the light-blue flag of the United Nations. I arrived

the following day, which is the date that is considered the official

beginning of the UN Mission's activities in Azerbaijan. In its

initial stage, the Mission consisted of a single room at the

Azerbaijan Hotel in Baku.

For anyone who remembers traveling in the former USSR at that

time, it's not hard to imagine the situation. But I knew what

to expect. There were the tiresome "hunting" expeditions

to find necessities like toilet paper and toothpaste as well

as the many Fellini-esque episodes dealing with the various "matryoshka"

at the hotel, namely the "goddess" of each floor of

the hotel, who turned out to be indispensable for our daily survival.

Requesting a simple bottle of mineral water often meant promptly

receiving a bottle of Soviet champagne. (Admittedly, it tasted

somewhat like Schweppes.) Of course, there was the dubious privilege

of room service delivered by a Marilyn Monroe-style, self-appointed

"waitress". I thought that I had already accumulated

so much Soviet and post-Soviet experience that nothing could

frighten me. Or at least, almost nothing...

I'll never forget the day I entered my 10-square-meter residence

/ office. I opened the terrace window and went out on the balcony

to hang up the flag. The thought of trying to find a flagpole

didn't even cross my mind; it would have been faster to fly to

New York to get one there. And so the noble flag was simply draped

across the balcony railing overlooking the Caspian and Azadlig

Square [Freedom Square, which was called Lenin Square during

the Soviet period].

A passerby on the square looked up with bewilderment at that

blue piece of cloth hanging from the fourth floor of the Intourist.

He seemed puzzled that the hotel had purchased blue bed sheets.

But as he came closer, he realized: "No, it was the blue

flag of the world -

renowned Napoli Soccer Team!" Suddenly, he greeted me with

a smile, waving his hands. "Maradona, Maradona!!!"

he shouted with enthusiasm for the great soccer player.

When I think back on that evening almost ten years ago and consider

the changes that have taken place in Baku since then, it seems

like another world, another era, another people. The atmosphere

at that time was somber. An aura of mild, but pervasive, sadness

had settled over the people, wiping out the initial euphoria

that had followed the collapse of the Soviet Union and the long-awaited

declaration of independence. The economic situation was desperate,

and talk of imminent oil fortunes did not alleviate the harshness

of the period. Above all, the pervasive specter of war engulfed

the country in a suffocating cloud.

Despite all of the hardships, difficulties and uncertainties,

the city maintained its warmth and passion for life. You could

feel it in the streets. Tiny cafes timidly started to open. Azerbaijan

was, above all, an outgoing society with a semi-Mediterranean

mentality. It was as if its tremendous culture and history, which

had been sealed for many years, was starting to emerge, chaotically

at first, but with hope and anticipation. It was a city of pioneers;

at least that's how it appeared to the first internationals who

arrived in the country soon after independence.

Transitions

Hiring national staff proved to be much more difficult than I

had expected. They were to provide the backbone of the office

in Baku, so I needed strong personnel. I was amazed at how highly

educated the applicants were. Many university professors, especially

economics professors, applied for the position of Chief Administrative

Officer. Unfortunately, their knowledge and experience was based

on principles that were not relevant to our program. They were

still part of the academic culture of the former Soviet Union.

In certain sectors, this was very valuable, but in others, completely

outdated.

After several days of hectic and unsuccessful searching, I decided

to look for very young, talented candidates who had virtually

no professional experience but potential for fast growth. I was

taking a risk that this would slow down our operation at the

beginning, but within time, it would promote the development

of a new class of staff entirely shaped by international civil

service standards.

One applicant that drew my attention was very young, but looked

even younger. In fact, he looked so young that one would have

wondered how he had arrived for the interview without being accompanied

by his father. However, I soon found out that he was very bright,

quick thinking and surprisingly well-informed on issues related

to international finance and multilateral organizations.

There was one thing about him that puzzled me. When I asked if

he could start work immediately, he hesitated. He said that it

would be difficult because he was working as Assistant to the

Minister of Finance, and there were issues at the Ministry that

no one but he could handle. I was surprised by his response,

which seemed somewhat arrogant for an applicant who had just

graduated from the university. But he was by far the best candidate,

so I decided to contact the Minister myself.

Sure enough, it turned out that this very shy, 20-something-looking

youth was responsible for relations with international financial

institutions. As such, he was indeed indispensable, not only

for the Minister but for the country itself, especially since

at that moment it was at the embryonic stages of working out

some projects with the World Bank and the IMF [International

Monetary Fund]. He had already been in Washington and participated

in meetings with senior staff of multilateral financial institutions.

After a long talk with the Minister, we finally agreed to "share"

the young Elkhan Aliyev on a part-time basis. He turned out to

be extraordinarily professional. Later he became a full-time

staff member in our office, probably one of the best and most

competent in the entire region.

Later on, while still very young, he won a competition to become

an International Finance Officer at the headquarters of FAO (Food

and Agricultural Organization) in Rome, where he resides today

with his family.

Many other talented Azerbaijani staff of the UN started in the

Baku office and are now serving in international posts in various

institutions. They represent the best of Azerbaijani professional

culture abroad, and we're proud to have recruited them.

Western Attitudes

I'd have to admit that we Westerners were slow to adapt and properly

comprehend the gigantic problems related to transition. It was,

in fact, a threefold process: (1) from former Soviet Republic

to independent, democratic Republic; (2) from command economy

to market economy; and (3) most importantly, from war to peace.

Some international officials believed this transition would be

effected by rapidly introducing economic reforms, but it turned

out to be much more difficult than that.

At the beginning of December 1993, I received a delegation from

an important international organization. I organized a breakfast

briefing to share my impressions about the importance of understanding

the context and culture of Azerbaijan, its peculiarities and

complexities, before undertaking adjustment programs.

Azerbaijan did not fit the definition of a developing country

in the traditional sense of the word. The global environment

was totally different, and I found our organizations slow to

adapt to the real political and economic needs of a region that

was new to us.

Soon after the briefing started, a waiter came to take our breakfast

orders. The official who was sitting to my right announced that

he wanted two fried eggs-sunny-side-up-bacon and porridge. The

hotel waiter looked at him in total confusion. I gently urged

my colleague to simply choose something from the breakfast buffet,

which admittedly wasn't a Sheraton-style selection. "The

concept of breakfast in this part of the world is somewhat different

than it is in Washington," I suggested. "Perhaps it

would be better not to embark on a risky experiment."

But he insisted and kept querying the distressed waiter for ten

minutes. Finally, the waiter said, "OK, OK, I know, I know,"

and left.

"You see, Paolo," said the foreign official, "with

these people, it's only a matter of perseverance to bring about

an evolution in their system and culture. In the end," he

added with evident satisfaction, "they're not bad people."

It took nearly half an hour for the waiter to return with the

order. When my colleague saw the dish that was placed in front

of him, he was speechless: it was an enormous, greasy, fried

chicken, with boiled potatoes and rice!

"Talk about evolution of the system," I said quietly.

"Actually, there isn't much difference between what you

ordered -

two eggs -

and what you received - a chicken! Perhaps certain 'systems' are able

to evolve more rapidly than you thought!"

Between the end of 1993 and the beginning of 1994, the United

Nations deployed a full system of UN agencies in Azerbaijan.

The first was UNHCR, which quickly set up an exemplar operation

to support the government in tackling a problem that was to become

the most painful and perplexing issue for the country: how to

care for nearly a million refugees.

UNHCR reacted quickly. In a matter of days, the office was set

up. Relief supplies were flown in almost immediately, bringing

first aid to a growing tide of refugees. The operation, performed

in conjunction with other UN organizations such as UNDP [Development

Program], WFP [World Food Program] and UNICEF [United Nations

Children's Fund], as well as non-governmental organizations,

enabled the refugee population to at least stave off starvation

and epidemics.

It became one of the greatest refugee crises in the world: nearly

a million refugees in a country with a population of barely 7

million. At a certain period, military hostilities became more

and more violent, and Azerbaijan continued to lose considerable

territory. The Azerbaijanis were in retreat when the region of

Fuzuli (near the Iranian border) came under heavy bombardment

[Summer 1993].

In one of the most difficult moments, the Speaker of Parliament,

Isa Gambar, himself a native of the Fuzuli region, decided to

go to the front line and remain with the troops until the end.

I decided to follow in order to assess what our response should

be. The events seemed to foretell an even larger humanitarian

disaster.

When I reached the front line, the residents had already been

evacuated from the zone, as it had been bombarded with continuous

shelling for several days. Troops were changed. New contingents

were being sent from Baku. As we neared the front line, we passed

columns of trucks carrying the troops who were returning from

the front. Our military escort, arranged by the Ministry of Defense,

was driving very quickly. As we approached, the sound of the

bombs became more and more violent. Every time we passed a truck,

I searched the expressions on the young soldiers' faces.

I was amazed at how very young the soldiers were and also by

their composed, impenetrable expressions. It was as if the life

had been knocked out of them. There was a striking difference

between the aged maturity of their expressions and the gentle

features of their adolescent faces. Their faces didn't show fear

or pain; instead they seemed void of all emotion - like the numbness

that sets in when a person lives under the constant threat of

death for a prolonged period of time.

After crossing the last checkpoint, we arrived at a small garrison

that had been almost completely destroyed. It was guarded by

a battalion of heavily armed troops. At that point, the explosive

sounds of the heavy bombardment became more frequent. The ground

shook periodically.

The door was opened very slowly by the Speaker's personal bodyguard.

I entered a small room, full of dust and rubble, where Isa Gambar

was sitting alone at a modest kitchen table. An empty chair in

front of him was the only other piece of furniture in the room.

Gambar was unshaven and rather pale, but his eyes were still

as strong as I had known them to be. His posture inspired a sense

of dignity. He seemed determined to reject the fatalism that

historic circumstances, at that point in time, seemed to have

already foreordained.

He wore a dark, rather dusty, jacket. No tie. An ashtray, the

only object on the table, was full of ashes and cigarette butts.

I shook hands with him, took a seat and waited, saying nothing.

"This used to be one of the most beautiful parts of Azerbaijan,"

he began. "In spring the color of the hills was gold with

wildflowers; at sunset, the hills would fade into the horizon,

depending on the colors of the clouds, and the sky...

"Why did you come?" he suddenly asked after a long

pause, looking me straight in the eye.

We had a one-hour meeting. I came to understand the gravity of

the situation: the troops probably would not be able to hold

onto the territory much longer.

The bombing became heavier and heavier. Gambar continued to smoke,

unperturbed. He spoke quietly and slowly. His voice was firm

and calm. Not once did he show signs of fear or anxiety. But

his tired eyes could not conceal the immense pain and anger he

felt in not being able to save the land of his people, his memories

and his life.

A bomb exploded nearby. The ground shook violently, causing all

the windows to shatter.

"It's time for you to go," Gambar told me. "A

bomb could fall on this place at any moment. It would be much

more heroic for you to persuade the international community to

stop this carnage, than to die with me here in this garrison."

The door opened suddenly, and the same bodyguard who had escorted

me in announced that it was no longer safe for us to continue

to stay there. We were urged to rush back to Baku immediately.

Gambar stood up and came over to me. He stretched out his hand

slowly and shook my hand firmly. There was nothing more to say.

As I was leaving I noticed that when he returned to his table,

he was about to light up his last cigarette, only to realize

that the matchbox was empty.

Baku's "Sharon

Stone"

It was November 1992. A meeting with the Minister of Foreign

Affairs had been scheduled for early the next morning. When the

telephone rang, I thought that I had overslept, so I jumped from

my bed to pick up the receiver. At that time I was still living

in the good old Azerbaijan Intourist Hotel.

"Hello, how are you?" came a woman's voice. I assumed

it was the secretary from the Ministry protocol.

"I'm fine, thank you," I replied, still quite groggy.

"Has the time of the meeting been confirmed?" I inquired.

"I don't know yet," she answered.

"I would appreciate it if you could confirm it at your earliest

convenience, as I still haven't alerted my colleagues."

"No problem, we can have a separate encounter with you first,

and then later with your colleagues," she replied promptly.

"No, sorry, that's not my style. I like being together with

my colleagues. I believe together is better. After that we can

meet individually."

"You're very demanding!"

"It's not a matter of being demanding. This was our agreement:

our first session would be a group meeting, and then I could

prepare for a one-on-one session."

"Won't you be tired by then?"

"Why should I be tired? I've had many similar experiences

with large groups. It's always been fine. Of course, sometimes

things may heat up a bit because everyone wants to participate

in his own way, but I can handle any unpleasant developments."

"Well, recently we had a bad experience with a group of

businessmen..."

"Oh no, please, we're not like that! We're the United Nations,

we have a different attitude. Fundamentally, we have, how shall

I say it...'a humanitarian approach' to our relations. Trust

me, we would never do anything against the will of our Azerbaijani

partner."

"A humanitarian approach, I like that! I've never heard

of that before!"

"That's because you've never had a UN Office here in Baku.

It's just a new experience. Don't worry. With us, you will change

many of your ways of doing business. We're here for that, no

need to be shy."

"It sounds very interesting - this 'humanitarian approach'. Anyway,

with or without the 'humanitarian approach', the cost will be

quite high, you know."

"Of course! But you see, we shouldn't be discouraged. Every

radical process of change entails high costs. It is unavoidable.

It's only a matter of being strong in the initial phase, and

gradually it gets better and better. I'm very optimistic."

"OK, then it's agreed. But I'll need some cash in advance."

"What cash?"

I must admit that I've never been very quick when it comes to

women. Whether it was the hour of the day, the stress or the

lack of sleep from the previous few days, I'll have to admit

that I was, indeed, particularly slow in catching on. I looked

at my watch and only then realized that it was 2 a.m. The person

on the phone was definitely not a secretary from the Foreign

Affairs protocol.

"You're not from protocol?"

"No, no, I'm not from protocol. I'm from Baku," the

young voice replied cheerily.

"But who are you?"

"Here they tell me that I look like Sharon Stone. And if

you open the door of your room in five minutes, you can see for

yourself..."

I was furious. I had just been awakened in the middle of the

night. I was tired and overworked, and the following day I had

an important meeting with the Minister, a very heavy schedule

and a lot of work to do.

At that time, a mission of senior UN colleagues was visiting

from New York. Why had I been the only one to be awakened and

suffer while my New York guests were sleeping so comfortably?

In the true spirit of UN partnership, I decided to solve this

situation before going back to sleep.

The head of the delegation was a German national-seasoned, respected

and, above all, very austere. He was also known for being very

active on issues concerning religious and humanitarian organizations:

in a word, "perfect" for what I had in mind.

It wasn't long before I passed along his name and number. Then

I went back to bed and slept soundly, without the slightest sense

of guilt.

The following morning the German arrived late for breakfast.

He was fuming.

"You know what happened to me last night? I can't believe

it!!! It's outrageous, simply outrageous. I was awakened by..."

"By what?" I asked.

"By a...you know, one of those girls...in the middle of

the night!!! This is very unpleasant. The most shocking thing

was that the woman knew my name and room number! I just can't

understand how she got it. She gave me a line about Sharon Stone

and who knows what else. I immediately hung up. I was so upset

that I couldn't go back to sleep. How could this have happened?!

It's a serious breach of security...We are all under threat here!

Tomorrow she could even call you, and we don't know what might

be behind all this! I'm going to complain to the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs! This is absolutely unacceptable..."

"I'm shocked," I told him. "A beautiful woman

named Sharon Stone phones you here in Baku, in the middle of

the night, talks to you using your real name and graciously proposes

an unsolicited visit to your room...

"You must have been very tired. It must have been jetlag

or the fatigue of traveling. You've just arrived from New York

and it was a long flight. I'm sure if you get some good, hot

chamomile tea and some sound sleep tonight, tomorrow everything

will be OK and your nights will be more tranquil."

"What, damn chamomile!!! That woman might call me again

and even attempt to force her way into my room. Do you understand

that?!!! At night this place is completely deserted...I need

police protection! Oh my God, this is a nightmare..." he

went on.

I replied, "But if everything you say is true about Sharon

Stone, how could it be a nightmare? Surely it was just a dream,

and a very sweet one"

Needless to say that when I finally admitted to the joke, we

all had a big laugh. The story made its way through the grapevine

of the United Nations.

The New Azerbaijan

In the spring of 1993 the situation became very tense. The tide

of the war turned against the Azerbaijani army, and large areas

of the country's territory were under occupation by the Armenian

military. Seurat Husseinov, an army colonel with a dubious past,

marched on Baku with a handful of troops loyal to him and seized

power, becoming Prime Minister in a bloodless coup.

I had always refused to have any dealings with him. I resisted

his attempts to organize official meetings with me, as I thought

doing so would somehow give him political credibility. I thought

that as representatives of the UN, we needed to send a clear

message. This was the most difficult period since independence,

and at a certain point, we felt that the course of events could

have erupted into civil war. Baku was under a curfew at night,

and several foreign companies were evacuated. We never evacuated,

but we did review and reinforce security measures for all of

the staff stationed in the country.

I became fascinated by the enormous cultural wealth, which has

hardly been known outside the country, as well as the fast pace

of economic and social development. Despite such progress, there

was no publication to document the events and profound changes

that were taking place and their impact on people's lives. We

decided to try to produce a Human Development Report to offer

a true picture of the "New Azerbaijan".

The government was suspicious of the idea. The old Soviet attitude

that every publication was to be used as an instrument of government

propaganda was deeply ingrained. But I knew that a global report

on the state of affairs in the country and its evolution would

promote a more realistic image of the country abroad and stimulate

debate about the country's future. I wanted the process to be

guided entirely by Azerbaijani intellectuals and scientists.

The issue of independence of judgment was of critical importance.

Key to the publication's final success was the selection of one

of the most respected Azerbaijani scientists as coordinator of

the report. When he first came to my office, I didn't know him

at all, but Professor Urkhan Alakbarov already had an international

reputation as a geneticist.

Just like all great men of science, he was a modest person with

gracious, simple manners. He was relatively short, in his early

50s and spoke broken English. Behind his very calm and serious

exterior, I could sense an enormous intellectual passion

- an energy that

his eyes could not hide.

He was the first person I met in Baku who was talking about sustainable

human development. He spoke about the future of Azerbaijan with

vision and realism, knowing full well that vast oil reserves

alone would not necessarily guarantee prosperity for everyone.

Many challenges lay ahead on Azerbaijan's path toward development.

Together we wanted to produce a book that would reveal the complexity

of the historic moment that we ourselves were witnessing. We

also wanted to portray the enormous potential of the nation.

He quickly assembled a team of independent Azerbaijani intellectuals

and scientists and began working on what came to be known as

the Azerbaijan Human Development Report.

It was the first-ever such report produced in the former Soviet

Union and became a milestone in providing a transparent glimpse

at the country's situation, both positive and negative. The report

was written with unprecedented openness and included guidelines

for future development. It included analysis from a broad range

of Azerbaijani representatives as well as international experts.

Even more remarkable was the fact that President Heydar Aliyev

himself launched the report, along with the Speaker of Parliament

and the Prime Minister, at a public ceremony. Aliyev understood

that he could benefit from allowing a larger margin of maneuverability

for the UN and its publications.

The ice was broken. From then on, many analytical studies and

essays about Azerbaijan began to be published and disseminated

throughout the country and abroad. As time went by, a new class

of intellectuals began to emerge. Gradually they brought to the

surface topics that up until then had been considered untouchable.

The Opera House

I was always amazed at how the Opera Theater kept operating,

even during the most tragic moments of the war. It had almost

no budget, and I learned later that it had remained open thanks

to the voluntary contributions of theater personnel and artists.

For a long period, during those early months and years, they

worked without any salary.

The first performance I attended was in late 1992. The theater

was nearly empty. There was very little electricity. The singers'

costumes were very old and in some cases, tattered. In fact,

some of the singers performed in their own clothes, instead of

costumes.

It had been a very harsh winter and there was no heating; the

temperature inside the theater was below zero [Celsius]. The

spectators, few that there were, wore their heavy coats, fur

hats and gloves, but were still freezing cold.

I was enchanted by the shining beauty of the representation and

by the spectacle of a nation that even during its most tragic

circumstances had not abandoned its cultural dignity and traditions.

A war was going on. There was little water or electricity. The

country was in a state of economic emergency, but still the opera

refused to close down.

Regrettably, for a long time, I was not able to do anything to

support the Opera Theater. As UN funds were very scarce, and

the humanitarian situation in the country was so disastrous,

no resources could be diverted from much-needed assistance, considering

that bilateral donors had never been particularly generous with

Azerbaijan.

In 1996 we finally succeeded in convincing a group of international

oil companies to finance a UN-sponsored Opera Trust Fund, in

support of the Azerbaijan Opera Theater. After long discussions,

the Fund was established at the very end of my tenure, with a

significant budget that allowed for the long-awaited rehabilitation

of the Opera.

Much credit for the survival of the Opera is due to its director,

Akif Malikov, a tireless and truly devoted cultural promoter.

His admirable and solitary efforts kept the Opera together during

the most difficult times.

For me, the Opera Theater was like a quiet refuge where I felt

at home more than anywhere else in Baku. When the challenges

of the political situation brought me to the edge of anger and

frustration, I would go to the Opera, no matter what was being

performed.

Many times I escaped to the empty theater and sat there alone

in one of the plush red velvet chairs, just for the pleasure

of being surrounded by the theater's beauty and breathing in

the atmosphere of its art and history. All of my battles would

be left outside those huge carved wooden doors, and harmony and

beauty would embrace me for a few brief moments.

Drug Control

"You see, Mr. Lembo, the core of Dostoyevsky's 'Crime and

Punishment' is in its many ambiguous intersections, including

the sense of guilt, collective human ethics, the individual's

code of conduct, public law, personal remorse (or the absence

of it) and divine judgment. When a society displays a harmonious

balance among all those elements, the job of the Prosecutor General

becomes unessential. Although we in Azerbaijan are far from having

found a proper equilibrium in our society, it seems more and

more that my functions in this country are of modest relevance."

Eldar Hassanov, Prosecutor General, was quite a rare character.

In almost every UN Mission around the world, relations with the

Prosecutor General are inevitably complex. That was not the case

in Azerbaijan. In fact, in the office of the Prosecutor General,

the UN had one of the most constructive relationships of all.

It is certainly rare to call on a senior government official

for an official visit and discuss matters of utmost relevance

amidst a quotation from Dostoyevsky, a comment about Michelangelo

and a reference to Mozart. But Eldar Hassanov was a true intellectual,

a cosmopolitan and, most importantly for me, a true believer

in the United Nations. He was always ready to receive me and

discuss the most delicate of subjects with a genuine commitment

to finding a solution. He did not hesitate to intervene personally

in highly controversial issues and assume the responsibility

for making sensitive decisions.

There was nothing I felt I couldn't discuss with him. We frequently

had disagreements, even disputes, but they never affected our

mutual respect for each other. He was a highly qualified man

of law who tried to exercise his authority with wisdom and justice.

He was Prosecutor at a very difficult time, and within the limits

of his mandate and considering the legacy that he had inherited,

he is remembered as someone who did his best to advance the rule

of law in his country.

He was particularly known for his competence in the drug-control

sphere, an area in which he had written several specialized publications

that were valued internationally. He and the Minister of Internal

Affairs, Ramil Usupov, deserve to be commended for their efforts

against drug trafficking.

The UN organized an International Conference on Drug Control

in Baku in 1997. An important agreement was reached there on

an international protocol (still referred to as the Baku Protocol)

to better coordinate international police efforts against narcotics

traffic. Overall, the law-enforcement authority in Baku always

provided excellent cooperation in our efforts to fight drug trafficking

in the region. When it came to drug control at that time, Azerbaijan

was a positive example that stood out among many other countries,

both inside and outside the region.

Rebuilding Horadiz

Horadiz [in the southwestern part of Azerbaijan near the Iranian

border] was one of the zones that were hit the hardest by the

war. The destruction there had been very extensive, and sporadic

shelling still took place even after the cease-fire agreement

[May 1994]. The region had been almost completely evacuated.

My thought was that it could become the starting point of a reconstruction

program that in phases could be extended to other neighboring

regions.

Our idea for reconstruction in the area was not met with much

enthusiasm at first. The word "reconstruction" had

not yet been used in any of the ongoing international programs.

Most of the international institutions feared that a full-scale

war would resume, destroying what was being reconstructed and

hampering future funding for international programs in the country.

On the contrary, I felt that launching a large-scale reconstruction

program in Horadiz, funded by international organizations, would

help restrain the bombardments from the other side of the border.

Any damage to the infrastructure that was being rehabilitated

would be seen as an act of hostility against the UN, not simply

against Azerbaijan. With an international witness on the scene,

it would have been irresponsible and dangerous to resume shelling.

I admit that it was a gamble, but as I think back on my activities

in Azerbaijan, I recognize that half of the decisions that we

made were risky. A seasoned diplomat in New York once told me

that there were two categories of staff in the UN: those who

start a project only when it is "safe", and those who

start a project only when it is just, no matter the risk. When

I began my career, I well understood the importance of good,

safe and traditional programs, but I decided to start implementing

them after I had retired as a consultant. In Baku, I was far

from retirement age.

We decided to create an Azerbaijani institution responsible for

overseeing the reconstruction activities in the country

- the ARRA (Agency

for Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of Areas damaged by the

war). Within a few months it was operational, and we started

formulating and implementing reconstruction programs. Initially,

it was funded by UNDP alone, but soon many other international

and bilateral donors joined.

We organized an international conference on reconstruction, where,

for the first time, oil companies were invited to get involved

with the program. It was an unqualified success, and we gained

sufficient resources to launch a large-scale plan. As I had hoped,

the military shelling came to a halt, and building activities

were carried out without incident. The Horadiz railway station

was reopened, and trains started traveling to and from the region.

Some of the media from a neighboring country accused me of "having

financed the re-opening of an Azerbaijani military supply line

by railway." There was a lot of noise about it in New York,

also. I answered that, given the speed and technology that the

Azerbaijani railway could afford at that time, it would have

been faster to utilize donkey caravans for a military supply

line.

In 1996 we celebrated United Nations Day [October 24] in Horadiz

with the first families who were returning to resettle the area.

[See "Horadiz:

Finally, Some Refugees are Heading Home," in AI 4.4, Winter

1996.

SEARCH at AZER.com.] We organized a simple celebration in town,

where we shared bread with the families who had moved into the

first houses that we had helped to reconstruct. Many of the Ambassadors

accepted the invitation to come out the four hours' distance

to Horadiz. A number of oil company managers and friends from

the international community joined them in a demonstration of

solidarity that was documented by CNN.

Abid Sharifov, Deputy Prime Minister in charge of construction

activities in the country, was my partner in the initiative.

Certainly, he's the person who deserves the credit for its success.

Sharifov looks like a character right out of a Francis Ford Coppola

film: he has a large build and a strong, deep voice, memorable

features, a prominent nose and brusque manners.

He was certainly not what one might call the quintessential diplomat.

He would only meet with you if he had something very concrete

to discuss. He was not willing to just chat and didn't even seem

to know how to do that. I liked this characteristic about him

and thought that we could work together well in that difficult

and politically charged venture related to the beginning of reconstruction

activities. In fact, he proved to be an excellent manager, surrounded

by people he had chosen who were equally professional. I felt

that my sympathy was reciprocated, although we were, in every

aspect, very different.

I had only one complaint about Sharifov: he was resolved to marry

me off in Azerbaijan. Now nothing is wrong with such an idea.

I was, and still am, a bachelor, and I'm certainly not against

the idea of marriage. Sharifov's thought was that he knew me

well, he knew Azerbaijani women well, and that Italians were

similar to Azerbaijanis, so he somehow felt the necessity to

take it upon himself to identify the right person for me so that

I would settle down.

What scared me most was that he undertook rebuilding Horadiz

and finding me a wife with the same intensity. He didn't earn

the nickname "Bulldozer" for nothing. I feared the

moment would come when I would exhaust my Italian resourcefulness

in escaping the final decision on the long procession of (nevertheless,

very appealing) candidates.

He would typically introduce me to a potential candidate at a

business dinner down at one of the sea resort restaurants, usually

in some romantic location. Just the appearance of Sharifov inculcated

the fear of God in all the restaurant personnel and management.

(Yes, I have to admit that Sharifov was very well known, and

the restaurant service for him and his friends was always solicitous.)

For the occasion, he would appear with a young "interpreter"

- a beautiful woman

from a good family. Of course, her linguistic qualifications

often left something to be desired. Instead of Azeri-English

translation, it was more frequently an Azeri-Azeri translation.

In any event I always had my (real) interpreter beside me, who

would proceed to interpret for me and for Sharifov's interpreter

as well.

When I met Sharifov for the last time at my farewell party [in

1997], he embraced me and said: "I have cracked many walls

in my life, but I didn't succeed in cracking your wall. You managed

to escape me, but you won't be able to escape for your entire

life."

During my final months in Baku, I was named "Man of the

Year" in Azerbaijan. I was given a bronze plaque at a ceremony

at the Respublica Palace. It is simply engraved: "To Paolo

Lembo, Azerbaijansevari." In Azeri, "Azerbaijansevari"

means something like, "The lover of Azerbaijan."

That plaque remains one of my fondest memories of Azerbaijan.

It seemed to symbolize my attachment to a people I identified

passionately with and with whom I had shared the first period

of that country's independence - the most difficult moments of peace and war,

hope and despair, success and failure. Never before had I experienced

that intensity and that fire for a cause that I had felt throughout

my stay in Azerbaijan. Perhaps it was because I was young

- I lived it with

all the unrestrained passion that is only possible during certain

seasons of one's life.

Toward the end of my tenure, I came to realize that I had become

quite a popular figure in Baku. When I walked the streets of

Baku, people recognized me and approached to offer a word of

sympathy, appreciation, or on occasion to complain about what

they thought the UN should have done but did not do (and they

were usually right). Sometimes they simply shook hands and smiled.

At restaurants, it was not unusual for bottles of champagne to

be offered by guests sitting at nearby tables.

On one of my last days in Baku, while I was waiting for my car

in front of one of the ministries, a taxi driver was smoking

a cigarette next to his very old Volga. He didn't recognize me,

so I decided to approach and ask him: "What do you think

of the UN here in Azerbaijan?"

"Ah," he answered, "Paolo Lembo!"

"No," I emphasized, "not 'Paolo Lembo'. 'The UN'."

"Yes, the UN -

Paolo Lembo!" he repeated.

"No, I didn't say anything about 'Paolo Lembo'. I said 'the

UN'!"

He appeared surprised. I was about to lose my patience. "Look,

Lembo is a man, like you and me, the UN is an institution. I'm

not asking about the man, I want to know your opinion about the

institution, the United Nations' organization in Azerbaijan?"

I paused and waited attentively. But my explanation made him

even more confused. The situation was hopeless.

"OK, I understand, so what do you think of the UN / Paolo

Lembo?"

"He's a good man."

"Yes, but why do you think the UN is a good organization?

What has it done here in Azerbaijan?" I continued.

"I do not know, but he is a good man."

"Can you tell me at least one good project that the UN has

done for the people of Azerbaijan in the last five years?"

He suddenly assumed a serious, almost philosophical attitude,

somewhat puzzled by my insistence.

He stopped smoking and looked up at the sky. My persistence seemed

to be paying off.

"He's a good man, a very good man," he said and slowly

left my investigation, which by then must have seemed rather

threatening.

I eventually realized that there was nothing I could do to separate

myself from the public image of the organization. I also had

the somewhat uncomfortable feeling that perhaps it was not so

good that I had arrived at a point where everyone knew me, but

nobody knew why I was known.

How long did I stay in Baku? Was it five years, fifteen years,

five months or five days? Perhaps the archives of our memory

classify the files of life's milestones according to the intensity

of emotions we have lived. In the end, the statistics of years,

months and days and their actual sequence gradually fades away.

When the moment came to leave, it almost took me by surprise.

I suddenly received a notification that my name was being proposed

for Tajikistan, which ranked as one of the most difficult duty

stations. The UN at that time was struggling to broker a peace

agreement. I have always been attracted by challenges, so I accepted.

I also felt that Azerbaijan had evolved tremendously since independence

and, given my background of working in countries under extremely

difficult circumstances, I could be more useful someplace else.

Still, leaving Baku felt strange to me. I had lived my life so

intensely on the Caspian bay that I wondered how I could live

without it. It turns out that I was mistaken, as the peace process

in Tajikistan proved to be an even more challenging adventure.

But never again would it be the same for me as it was in Baku,

in terms of witnessing the birth of a nation.

After my departure from Baku, some thought that the UN should

be more neutral. I have always believed that the UN should be

impartial, but never neutral. It must have the courage to take

sides with the losers and the forgotten. If the UN doesn't do

it, who will? I have always refused to initiate projects that

would only appease government officials and bind them to the

UN with a few material privileges. I have never been able to

be everyone's friend, and I'm convinced that there are still

people in Baku who do not sleep well when they think of my name.

I would be the first to admit that not every project I promoted

was successful; however, each of them did constitute an effort

to work in an area where no one else had worked before. The important

thing was the aim, not the project.

In the larger picture of Azerbaijan's history during the first

decade of its independence, the UN played a marginal role. Within

that, my personal role was insignificant. In Azerbaijan I only

began a small fraction of the projects I would have liked to

have done. I left the country with the regret of having received

much more from the people than it was possible to give them.

My story is the simple tale of a UN bureaucrat who arrived in

Baku one day in October 1992, as a young dreamer, with a suitcase

and a big blue flag. I left several years later as a man who

had lost some beliefs but gained more faith in values.

On my last ride from Baku to the airport, I sat in the car with

two people who had been close to me throughout my mission in

Azerbaijan: Mahir, my assistant, and Fuad, my security officer.

I looked out at the beautiful architecture of the buildings

- the elegant decorations

of turn-of-the-century palaces that had recently been restored.

I was amazed at the incredible combination of styles, art, fashions

and customs that could be read in the buildings that lined the

city's avenues. What a unique place this was, I thought. And

I realized that I had had that exact same thought while entering

the city for the first time a few years earlier.

At a certain point, the car changed its route and headed toward

the city center.

"Where are we going?" I asked.

"One last appointment, Mr. Lembo," Mahir explained.

We pulled up in front of the Opera Theater, and a guard appeared

to open the main entrance door. I was invited to enter the foyer,

where a valet was waiting, alone. He ushered me into the theater,

to a seat in the center of the music hall. He then smiled and

left, without saying a word.

The theater was completely empty. Never had it looked to me as

beautiful as it did at that moment. In the silence, I felt suspended

between the elegant rows of empty, red velvet seats and the celestial

frescoes of the theater's ceiling.

Only then, for the first time, did I note the graceful golden

cherubs carved on the main balcony. The left cherub seemed to

be looking in my direction. There was something in the expression

of its face that caught my attention. I stood up, slowly moving

toward it. I noted that its expression was not completely happy;

a tiny frown between its eyes revealed a sentiment of apprehension,

something that contrasted with the joyful expression on its face.

It was as if it feared an imminent event that it did not wish

to happen, but was conscious of its inevitability. What did the

cherub fear?

Suddenly, a light appeared on the stage, and to my surprise,

a tenor appeared. The grand silhouette of his body was backlit.

The rest of the stage remained dark, as did the rest of the theater.

He greeted me, the only spectator, with a slight nod of his head

and after a pause, began singing. I immediately recognized his

song as "E Lucevan Le Stelle" [And the Stars Were Shining]

from Puccini's "Tosca" - my favorite aria.

His was a powerful, elegant voice; the notes were strong and

pure. He sang for a few minutes with the great intensity, passion

and talent that made him the most reputed tenor in the Caucasus.

I listened, overwhelmed.

When he finished he came up to the edge of the stage, stopped

and said with a perfect Italian accent: "Grazie, Paolo."

I slowly stood up and looked at him, speechless for what seemed

like an eternity. Then the lights faded and the theater was cast

into darkness.

It was cold at the airport, and for once, the Turkish Airlines

Baku-Istanbul flight was not overbooked. In fact, there were

only a few passengers waiting in the lounge. A fat Turkish tradesman

was smoking, reading a football newspaper with deep concentration;

an Azerbaijani yuppie was restlessly talking on his cellular

phone (a new fashion in Baku at the time); a mother was screaming

and running after her two mischievous sons, who enjoyed kicking

passengers' suitcases; a small group of custom officers, bored

as always, were discussing the prices of a vacation to Anatolia

[Turkey], mechanically following with their eyes the legs of

the stewardesses who were passing by. Every detail of that ordinary

scene was as familiar to me as if it were the last chapter in

a book that I've enjoyed reading over and over again.

I waited for everyone else to embark before I approached the

plane. Mahir and Fuad insisted on following me to the plane.

I embraced them both. They asked if I would ever come back. I

answered that I would. I did not know how or when, but yes, one

day I would come back. They wished me luck in Tajikistan.

I climbed the stairs to the plane, but just before entering,

I heard someone call me. I turned back, but the tarmac was deserted.

I looked out on the horizon and could see the sun slowly disappearing

into the horizon of the silvery blue sea.

"Sir, could you please board; we're already late,"

said the blonde hostess at the plane's door, in her tender Turkish

accent.

"Yes, I'm coming." I had the impression that someone

was calling me, but it must have just been the sound of the wind.

I now live in another beautiful city along the Mediterranean

coast. In the evenings, when I walk along the seaside boulevard,

sometimes I hear the whisper of the wind of Baku calling me and

I feel it gently touching my face. But it's only for a moment.

Soon I recognize that it is not the same wind. It is not the

same wind...

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.3) Autumn 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.3 (Autumn 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|