|

Changing Our

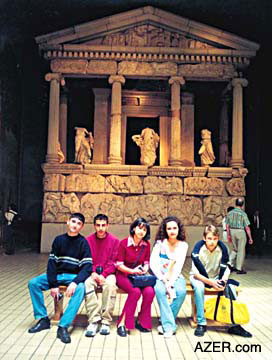

Tune

Left: Bulbul School got a "face lift" this past summer 2001 - sandblasting, paint and new windows. Right: Before refurbishment. Nigar Asgarova became Director of Bulbul Music School in 1992, just after Azerbaijan became independent. With lots of hard work and persuasion, she was able to turn the school around and make dramatic improvements in its appearance. Responding to her call for help, parents and teachers stepped in with donations and hard work to repair the building, fix the roof and make other much-needed repairs in the classrooms and halls. Recently, the windows were replaced through the help of the Ministry of Education, and the exterior was sandblasted and painted. However, Nigar Khanim (Mrs. Nigar, as she is fondly called by faculty and students alike) says that there is still a great deal that needs to be done. Today she is focusing on trying to introduce overdue changes to the school's curriculum and approach in order to give it a theoretical basis that is distinctively Azerbaijani. Here she discusses some of these major changes, particularly how more and more students are studying Azerbaijani music and learning to play traditional instruments like the tar and kamancha in addition to Western instruments such as the piano, violin, viola and cello. I believe that Azerbaijan has a rich deposit of music that has yet to be unearthed. But this won't happen until young Azerbaijanis become more familiar with their own culture. It's really a shame, but today's youth know very little about Azerbaijani traditional music. I would love for my students to know how rich their country's own music is. Famous Azerbaijani composers like Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Gara Garayev, Fikrat Amirov, Jovdat Hajiyev, Arif Malikov, Vasif Adigozalov, Hasan and Azer Rezayev were very familiar with Azerbaijan's music, including the traditional modal form known as mugham. They wrote operas, symphonies and other works incorporating traditional melodies and modes. Just consider Amirov's "Kurd-Afshari" (1949), "Shur" (1946) and "Gulustan Bayati-Shiraz" (1968) - all three symphonies were based on mughams, as was Niyazi's "Rast" symphony.  So many other great pieces like these could be written if our students really understood the roots of Azerbaijani music. Why do you think George Gershwin's works are so popular throughout the world? He based them on American music, the music of his roots. But we've had very few Azerbaijani composers who have used their own roots. Every composer should "drink water from his own land," as we are fond of saying. If he "drinks water" from other lands, then the world won't recognize him as being distinct. Then and Now During the Soviet period, we weren't supposed to "drink water from our own land". Children were encouraged to study music, and very intensely, but only European and Russian music. Instead of studying traditional musical instruments like the tar or kamancha, most children studied Western instruments like the piano, violin or cello. In the past decade, however, many more students have come to our school to study traditional Azerbaijani instruments and music. Many of them have moved here from the regions - some of them from Nagorno-Karabakh, which is now militarily occupied by Armenia. Karabakh is known for its rich reservoir of musical talent. Every family tends to have at least one musician, and the area was known as the center of khananda (traditional) singing.  Today we have a large proportion of tar players, kamancha players and traditional singers. With such a large pool of talent, we've been able to start a folk instrument orchestra, using instruments such as the tar, kamancha, balaban, zurna and tutak. In the entire history of our school, we've never had an orchestra of national musical instruments before. New Curriculum Before Azerbaijan became independent, the school's curriculum was imposed by Moscow. Our school's teachers were not allowed to deviate from this program. Much of the curriculum focused on Russian music literature and Russian music history; very little time was devoted to Azerbaijani music literature. The curriculum that we used was basically identical to that of other music schools across the USSR. Students in Baku, Kazakhstan and Georgia all studied the same composers - such as Beethoven, Bach, Tchaikovsky and Glinka - and performed the same pieces. They didn't learn about composers from their own republic until their final year of school, at age 17. Today we are free to prepare our own curriculum and programs and even to choose our own teaching methods. We have been able to designate more time for Azerbaijani music literature, history and national culture. During the Soviet era, we only taught three Azerbaijani composers: Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Gara Garayev and Fikrat Amirov. But today, we also include the likes of Vasif Adigozalov, Arif Malikov, Musa Mirzayev, Tofig Guliyev, Agshin Alizade, Jovdat Hajiyev and others. However, the time set aside for Azerbaijani music is still far too little - only two hours a week over two years. In the future, I want to begin teaching Azerbaijani music to students in the first grade. Teaching Mugham I consider it a great loss for Azerbaijani culture that our youth do not know about mugham and the modes upon which our traditional music is based. Azerbaijan has seven primary mugham modes, each one divided into at least seven parts. But up until the present, we've only taught students about major and minor keys, the foundation for Western music. Our music would be greatly enriched if we taught them the modes of mugham as well.  Aliyev. In 1945, Uzeyir Hajibeyov wrote a valuable book about the basics of mugham, called "Principles of Azerbaijani Music." Unfortunately, up until recently, we haven't been able to study this book in depth. Right now, we're looking for specialists who are familiar with mugham and will be able to teach it. Our school has seven different departments: piano, string instruments, wind instruments, music theory, chorus conducting, composition and Azerbaijani national instruments. In each department, students are taught about European and Russian music first, before moving on to Azerbaijani music in their last few years of study. This strategy is not always effective, especially for children who come from the regions to study traditional singing. Western music is alien to them. We try to teach them Bach and Beethoven, but they just can't grasp these other styles of music. Even by the 11th grade, they still don't understand these composers. Instead of sticking to the old program, we need to teach these khananda students Azerbaijani music first; only after that should we be teaching them foreign composers. International Relations Another development is that now we can make relationships with foreigners and foreign countries. In the past, it would have been impossible to have even invited a foreigner to our school. I would not have had the right to invite a foreign journalist to my office without informing the Minister of Education. He, in turn, would have had to confer with others. Decisions were made in Moscow regarding who to meet with, who not to meet with. Now if we receive invitations from other countries, we don't have to ask anyone about it - not even the Ministry of Education. I think this is one of the greatest benefits of our independence - that we can forge our own friendships and relationships. Pressing Needs In order for us to teach Azerbaijani music and continue to teach Western music, we need to meet many pressing needs. Music literature books are in very short supply at our school, especially books related to Azerbaijani music. Without these books, it's very, very difficult for our teachers to teach.  We don't have modern equipment like TV sets or CD players. When our teachers want to play certain pieces for students, they have to make do with Soviet-era equipment and very old records. We need to have rooms that are equipped with modern sound equipment for our music literature classes. We need to have a center where recordings can be kept so that teachers in a classroom can request a song to be played; then a person from that center would play it so that it could be heard in the classroom. But it's not enough just to listen to a piece once during class time; the students should be able to go to a decent music library where they can listen to pieces over and over again. Unfortunately, students don't have this opportunity because we don't have enough money to provide equipment. It's very challenging to find printed or recorded music for 20th-century Azerbaijani composers. Many of their works have never been published. Arif Malikov has presented us with his records, so we can play them for students. But since we don't material from the other composers, we can only give our students information about their lives and the names of their works.  Left: Bulbul School students who received the President's Golden Book of Young Talents award in 1999: Ayyub Guliyev (tarist), Amil Hasanov (singer). Slow Process We're happy that Azerbaijan is independent now, but we still feel bogged down by the legacy of our Soviet past. We're moving forward, but with baby steps. I believe it will take several generations for Azerbaijani music to return to the high level that it reached in the early 20th century, when giants like Hajibeyov were at the head of our music development. We still haven't compiled the new programs that we want to have. We still don't have the resources to offer our students more opportunities for learning. Besides these obstacles, we also need to change our mentality. We need to find qualified teachers who are able to teach Azerbaijani music according to the new program. And this process will take a long time. But I think that finally we are on the right track. Our independence has already made a significant impact on the development of our education in music. Bulbul quintet visits London This past June a group of five students from one of Baku's most prestigious music schools got the chance to visit some of England's finest music schools. The highly qualified musicians who were chosen to represent the school included three violinists: Rovshan Amrahov, Sabina Guliyeva and Anar Aliyev; cellist Denis Utkin; and pianist Saida Taghizade. The idea for the trip came from Linda Lawrence, wife of BP's then head of Media and Public Relations in Baku. Lawrence, a former chemistry teacher from St. Paul's Girls' School in London, had lived in Baku for the past two years and enjoyed the superb quality of music. "I decided to see if we could develop a relationship between the music schools here in Azerbaijan and the well-known music schools of London. I hope there will be an ongoing partnership." The Azerbaijani youth visited two music schools: the exclusive Yehudi Menuhin School in Surrey (named after the famous violinist) and the St. Paul's Boys School and Girls School in London. But the highlight of the trip came when BBC asked them to perform a 15-minute concert, which was broadcast back home live to Azerbaijan. Violinist Rovshan Amrahov played "Caprice No. 9" by Paganini, violinist Sabina Guliyeva played "Carmen" by Pablo de Sarasate and pianist Saida Taghizade played Rachmaninov's "Musical Moment". The quartet, which included Rovshan, Sabina, cellist Denis Utkin and violinist Anar Aliyev, played "Scherzo" by Sultan Hajibeyov, "Dalilo" by Khayyam Mirzazade and "Quartet No. 2", first part, by Mozart. While in England, the students gained exposure to new ideas that they hope they'll be able to implement back home. "We watched an improvisation played by a trio of violin, cello and piano. The instructor suggested a main theme, and then a trio of students had to improvise and continue it. We'd love to try this out with a quintet of piano and stringed instruments." Sight-reading also fascinated them. Rovshan commented, "It takes a very professional musician to be able to play something right away if they've never seen the piece before. There are competitions for sight-reading in Moscow, Berlin and London, but we have never had that kind of training in Baku." Another difference they found was that British students had access to labs where they could listen to recordings and computers where they could compose music. "It also impressed us that the students at the Menuhin School often take part in international competitions," Rovshan added. "For instance, their violin players participate in the Pablo Sarasate International Violin Competition in Spain. We would love to be able to do that." The students' itinerary included concerts and a workshop about composer Benjamin Britten as well as sightseeing. "They saw a great deal of London," Lawrence said. "I tried to show them as much as possible in that one week including the Buckingham Palace, Downing Street, the Houses of Parliament, the New Tate and the Covent Garden." Behind the scenes, helping to make such a dream possible for these youth were two Azerbaijani families and a British family that they stayed with in London. British Airways that provided the flights between the two capitals. For more information about Bulbul Music School, contact Nigar Asgarova at Tel: (994-12) 92-61-69 or 32-78-19. ____ From Azerbaijan International (9.4) Winter 2001. © Azerbaijan International 2002. All rights reserved. Back to Index

AI 9.4 (Winter 2001) |