|

Spring 2002 (10.1)

Pages

44-49

Khojali

Eyewitness

Account From the Following Day (1992)

by Thomas Goltz

Goltz (same article below)

Eyewitness Khojali

(magazine format) PDF 1.2 MB

See articles about Khojali by

Thomas Goltz:

Khojali: A Decade of Useless

War Remembered (AI 10.1, Spring 2001)

Khojali:

Facts

(AI 13.1, Spring 2005)

Khojali:

13

Years Later: Remember, But Be Sure to Preserve Your Souls

(AI 13.1, Spring 2005)

Khojali: How to Spell

"X-O-J-A-L-I"? (AI 10.1, Spring 2001)

Also:

Khojali: Quotes: Never

Forget Khojali and other Massacres by Photographer Reza (1999)

Khojali: Documenting

the Horrors of Karabakh: Chingiz Mustafayev

in Action

by Vahid Mustafayev (AI 7.3, Autumn 1999)

Khojali: Finally

Documented in U.S. Congressional Record by Dan Burton (AI 13.1, Spring 2005)

Journalist Thomas Goltz was the first

to break the story of the Khojali massacre in the international

press when his February 27, 1992 article appeared in the Washington

Post. The day after the massacre, Goltz had visited the neighboring

city of Aghdam (estimated population 60,000) and witnessed the

Khojali survivors straggling in with tales of the horror that

they had just passed through. It's a tragic memory that will

never leave him, and a story that we think the world deserves

to know. Journalist Thomas Goltz was the first

to break the story of the Khojali massacre in the international

press when his February 27, 1992 article appeared in the Washington

Post. The day after the massacre, Goltz had visited the neighboring

city of Aghdam (estimated population 60,000) and witnessed the

Khojali survivors straggling in with tales of the horror that

they had just passed through. It's a tragic memory that will

never leave him, and a story that we think the world deserves

to know.

The following chapter, entitled "Khojali", is from

Goltz's book "Azerbaijan Diary" (M.E. Sharpe, 1998,

Armonk, NY). It appears here in Azerbaijan International with

the author's permission, in a slightly abridged form.

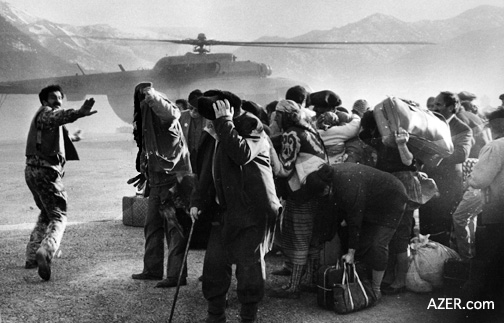

Above: Refugees from the Karabakh War, frantic

to get away from the invading Armenian troops. In their haste,

they had to leave almost all of their possessions behind. Scores,

hundreds, possibly even a thousand had been slaughtered in a

turkey-shoot of civilians and their handful of defenders. Aside

from counting every corpse, there was no way to tell how many

had died. Most of the bodies remained inaccessible, in the no-man's

land between the lines that had become a killing zone and a picnic

for crows.

______

February 26th, 1992 seemed like a regular working day. Iranian

Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati was back in Baku to finally

bestow diplomatic recognition on Azerbaijan, as well as to respond

to the recent comments by U.S. Secretary of State James Baker

III about the growing threat of Iranian influence in the Caucasus

and Central Asia.

The wiry Iranian emissary insisted that

it was not the Islamic Republic of Iran that posed a threat to

the region, but rather the United States of America. In addition

to being the country most responsible for the continued bloodshed

throughout the world, it was America, he proposed, that was actively

fomenting the conflict in Karabakh. By way of contrast, he noted

that the Islamic Republic was interested in peace between nations

and peoples. To that end, Dr. Velayati had brought a peace plan

for the increasingly bloody and senseless conflict in Karabakh

- and one that both Armenia and Azerbaijan had agreed to sign.

He himself was planning to visit Karabakh the next day. The wiry Iranian emissary insisted that

it was not the Islamic Republic of Iran that posed a threat to

the region, but rather the United States of America. In addition

to being the country most responsible for the continued bloodshed

throughout the world, it was America, he proposed, that was actively

fomenting the conflict in Karabakh. By way of contrast, he noted

that the Islamic Republic was interested in peace between nations

and peoples. To that end, Dr. Velayati had brought a peace plan

for the increasingly bloody and senseless conflict in Karabakh

- and one that both Armenia and Azerbaijan had agreed to sign.

He himself was planning to visit Karabakh the next day.

Above: Karabakh's mountainous terrain proved

difficult for Azerbaijani troops, shown here in their Soviet

tanks.

That was news. I was getting ready to file a story with the Washington

Post when Hijran, my wife, came rushing in. She had been on the

telephone with the Popular Front and had heard some very distressing

news. Sources in Aghdam were reporting a stream of Azeri refugees

filling the streets of the city, fleeing a massive attack in

Karabakh.

There had been many exaggerated reports about the conflict from

both sides. I wondered if this was just another example, but

I thought it best to start working the phone. Strangely, no one

in the government answered. Perhaps they were all at the Gulistan

Palace having dinner with the Iranian delegation. I waited a

while, and then started trying to contact people at home. Around

midnight, I got through to Vafa Guluzade [an advisor to President

Mutalibov].

"Sorry for calling so late," I apologized. "But

what about this rumor"

"I can't talk about it," said Vafa, cutting me off

and hanging up.

An ominous feeling filled my gut. Vafa was usually polite - to

a fault. Perhaps he had been sleeping? I decided to call back

again anyway, but the number stayed busy for the next half hour.

Maybe he had left the phone off the hook, I thought. I made one

last effort. Finally, the call got through.

"Vafa," I said, again apologizing. "What's going

on?"

"Something terrible has happened," he groaned.

"What?"

"There's been a massacre," he said.

"Where?"

"In Karabakh, a town called Khojali," he said, and

then he hung up the phone again.

Khojali?!

I had been there before. Twice, in fact. The first time was in

September [1991], when a number of reporters and I had staked

out the airport waiting for Russian President Boris Yeltsin to

come through. The last time had been just a month before - in

January 1992. By that time the only way to get to Khojali was

by helicopter because the Armenians had severed the road link

to Aghdam. I remembered that little adventure all too well.

Skeptical of the many reports coming from the Armenian side that

the Azeris were massively armed and that their helicopters were

"buzzing" Armenian villages, I had traveled to Aghdam

with Journalist Hugh Pope, then of the [London] Independent to

chat with refugees about their situation.

Refugees were easy to find in Aghdam. In fact, they were all

over the place. The greatest concentration was at the local airfield

for the simple reason that many of the refugees were tired of

being refugees: they wanted to go back home to Khojali. Pride

had overpowered their common sense. One was a 35-year-old mother

of four by the name of Zumrud Eyvazova. When I asked why she

was returning, she said it was better "to die in Karabakh

than beg in the streets of Aghdam."

"Why can't the government open the road?" shouted Zumrud

in my ear over the roar of the nearby chopper's engines, "Why

are they making us fly in like ducks-easy targets to shoot at?"

I didn't have an answer.

Then someone lurched toward me from across the airfield. It was

Arif Hajiyev, Commander of Airport Security at Khojali and the

gentleman who had saved us from the Aghdam drunks during Yeltsin's

visit three months earlier. He had been pretty chipper then,

but despite the broad smile that he gave me, I could see that

it was no longer fun and games. I asked him how the situation

was in his hometown.

"Come on," said Hajiyev. "Let's go to Khojali

- you'll see for yourself and you can write the truth-if you

dare."

Behind him an MI-8 helicopter waited, its blades slowly turning.

A mass of refugees were clawing their way aboard. The chopper

was already dangerously overloaded with people and foodstuffs.

There was even more luggage waiting on the tarmac, including

a rusted 70mm cannon and various boxes of ammunition.

"I'm not going," said Pope, "I've got a wife and

kids."

The blades began spinning faster, and I had to make a quick decision.

"See you later," I said, wondering if I ever would.

I climbed on board, one of more than 50 people on a craft designed

for 24, in addition to the numerous munitions and provisions.

"This is insane," I remember telling myself. "There's

still time to get off."

And then it was too late. With a lurch, we lifted off and my

stomach rushed up to my ears. I could see Pope waving at me as

he walked off the field. Somehow I wished I had stayed behind

with him on "terra firma". The MI-8 wound its way up

to a flight altitude of 3,500 feet-high enough to sail over the

Asgaran Gap to Khojali and avoid Armenian ground fire. Two dozen

helicopters had been hit during the past two months. In November

[1991], one helicopter had crashed, resulting in the deaths of

numerous top officials.

Another "bird" had been hit the week before. Even the

machine we were flying in had picked up a round in the fuel tank

just a week before. That's what the flight engineer told me.

Luckily, the fuel supply had been low and the bullet had come

in high. This was all so very reassuring to learn as we plugged

on through the Asgaran Gap, bucking headwinds and sleet.

Through breaks in the cloud cover I could see trucks and cars

on the roads below. They were Armenian machines, fueled by gas

and diesel brought in via their own air-bridge from Armenia (or,

perhaps, even purchased from Azeri war profiteers). Finally and

I should add, "mercifully", after a journey that seemed

to take hours but really only lasted maybe 20 minutes, we began

our circular descent to the Khojali airfield. Any one who has

ever been aboard such a flight can appreciate the relief I felt

when the wheels touched ground.

"I'm alive!" I wanted to shout, but thought it most

appropriate to stay cool and act like I did such things twice

a day.

"How do you feel?" Arif Hajiyev asked me.

"Normalno," I lied in Russian, cool as cake.

Meanwhile, the chopper was mobbed by residents - some coming

to greet loved ones who had returned, others trying to be the

first aboard for the helicopter's return trip. Everyone had gathered

to hear the most recent news about the rest of Azerbaijan - newspapers,

gossip, rumors.

No phones were working in Khojali. In fact, nothing worked there.

No electricity. No heating oil. No running water. The only link

with the outside world was the helicopter that was under constant

threat with each run. The isolation of the place became all too

apparent as night fell. I joined Hajiyev and some of his men

in the makeshift mess hall of the tiny garrison, and while we

were dining by the light of flickering candlelight on Soviet

army Spam with raw onions and stale bread, he gave me what might

be called a front-line briefing.

The situation was bad and getting worse, a depressed Hajiyev

told me. The Armenians had taken all the outlying villages, one

by one, over the previous three months. Only two towns remained

in Azeri hands: Khojali and Shusha, and the road between them

had already been cut. While I knew the situation had been deteriorating,

I had no idea it was so bad.

"It's because you believe what they say in Baku," Arif

jeered. "We're being sold out. Utterly sold out!

"Baku could open the road to Aghdam in a day if the government

wanted to," he said. He now believed the government actually

wanted the Karabakh business to simmer on in order to distract

public attention while the elite continued to plunder the country.

"If you write that and attribute it to me, I'll deny it,"

he said. "But it's true."

The 60-odd men under his command lacked both the weapons and

training to defend the perimeter. The only Azeri soldiers worth

their salt were four veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan

who had volunteered to try to bring some discipline into the

ranks.

The rest were green horns. If the Armenians shot off a single

round, they answered with a barrage of fire, wasting half of

their precious ammunition. And thus we passed the night. Around

2 a.m., I was awakened by a distant burst of fire coming from

the direction of a neighboring Armenian town called Laraguk,

about 500 yards away from a part of Khojali called, ironically

enough, "Helsinki Houses."

The Armenian sniper fire was returned with at least 100 rounds

from the Azeri side, including bursts of cannon fire from an

old BTR, newly acquired from some Russian deserter. It was the

only mechanized weaponry that I saw in the hands of the Azeris.

The firefight continued sporadically until dawn, making it impossible

to sleep.

No one knew when the Armenians would make their final push to

take the town, but everyone knew that one night they would. Khojali

controlled the Stepanakert [Khankandi] airport and was clearly

a major objective for the Armenians. They had to take it. I remember

thinking to myself: "I would, if I were them." With

that thought came another that made me very uneasy: "What

would the residents do when the Armenians did attack?"

In the morning, people were just standing around - literally.

There was not a single teashop or restaurant in which to idle

away the time. Men stood in small knots along the mud and graveled

streets, waiting. The only person I saw actually doing something

was a rather fat girl who worked as a sales clerk in the one

fabric shop where there was nothing to sell. I spotted her waddling

in to work at nine that morning. She was so intense about what

she was doing that I decided to follow her into the shop. But

the next time I saw her was when I was viewing a video. She was

lying dead on the ground amidst a pile of other corpses - but

that would come later. The rest of the townspeople just hung

around, waiting for the ax to fall. I just prayed that it wouldn't

happen while I was there.

We wiled away the morning, hanging around the airport. A photographer

from an Azeri news agency happened to be around, so the military

boys put on a good show, rolling out of their bunkers and running

behind the old BTR, guns blazing.

"Let's do it again, but this time, let me take pictures

from the front," the cameraman had suggested.

I felt sick and refused to have anything to do with such theatrics.

"These guys are going to die," I told myself. "And

I don't want to die with them just because they're stupid enough

to be shooting at shadows that fire back."

Arif Hajiyev seemed to agree. We sat together in silence, watching

his men pose for the camera, running hither and yon, full of

bravado.

"Let's try that one again!" crowed the photographer.

I felt sick and refused to take a single photo or write a single

note.

Finally, around noon, I heard the telltale whine of the chopper

approaching from over the gap. Thank God! I let out a sigh of

relief while trying to look indifferent. Then I made my way toward

the airfield, just in time to see the overloaded bird disgorge

its cargo of food, weapons and returning refugees. One kid got

off with a canary in a cage, or maybe he was getting on. There

were so many people at the airport, trying to get on and off

that lone bird. I was merely one of them.

It seemed more were trying to get on than off. I desperately

wanted on myself. I didn't care that the chopper was carrying

twice or three times its weight limit, nor that part of the weight

was a corpse - one of Hajiyev's boys picked off by a sniper the

night before. I wondered if we had shared that Soviet-style Spam

dinner together by candlelight the night before, but thought

it too impolite to pull back the death sheet to stare. The engines

gunned and whined, and we lifted with a lurch - but this time

I was not afraid of the flight. I just wanted out. We climbed

and climbed, circling high in the sky and blowing over the Asgaran

Gap at 3,500 feet with tail winds. Maybe we took some ground

fire; I don't know. But I did know one thing: I would never go

back to Khojali again.

There was no need for vows. The last helicopter into Khojali

- that town that had already been surrounded by Armenians - flew

on February 13th.

The last food, except for locally grown potatoes, ran out on

the 21st. The clock was rapidly ticking toward doom. It struck

on the night of February 26th-the date that Armenians commemorate

the attack on Armenians at Sumgayit in 1988.

***

We left Baku by car at seven in the morning and drove as quickly

as we could across the monotonous flats of central Azerbaijan.

Brown cotton fields stretched along the horizon. As we roared

by, hunters standing along the roadside held up ducks that they

had just bagged. We stopped for gas in a town named Tartar and

asked the local mayor what was happening in Aghdam. He said he

didn't know anything. We stopped again in another town called

Barda and again took a moment to inquire about events and rumors.

Clueless looks greeted us.

We were starting to think that the whole thing was a colossal

bum steer when we arrived in Aghdam and drove into the middle

of town, looking for a bite to eat. It was there that we ran

into the refugees. There were 10, then 20, then hundreds of screaming,

wailing residents - all from Khojali. Many of them recognized

me because of my previous visits to their town. They clutched

at my clothes, babbling out the names of their dead relatives

and friends, all the while dragging me to the morgue attached

to the main mosque in town to show me their deceased loved ones.

At first we found it hard to believe what the survivors were

saying. The Armenians had surrounded Khojali and delivered an

ultimatum: "Get out or die." Then came a babble of

details about the final days, many concerning Commander Arif

Hajiyev.

Sensing doom, Arif had begged the government to bring in choppers

to save at least a few of the civilians, but Baku had done nothing.

Then, on the night of February 25th, Armenian "fedayeen"

hit the town from three sides. The fourth side had been left

open, creating a funnel through which refugees could escape.

Arif gave the order to evacuate: the soldiers would run interference

along the hillside of the Gorgor River Valley, while the women,

children and "aghsaggals" [gray-bearded ones - wise

elders of the village] escaped. Groping their way through the

night under fire, the refugees had arrived at the outskirts of

a village called Nakhjivanli, on the cusp of Karabakh, by the

morning of February 26th. They crossed the road there and began

working their way downhill toward the forward Azeri lines and

the city Aghdam, now only some six miles away via the Azeri outpost

at Shelli.

It was there in the foothills of the mountains even within sight

of safety, that the greatest horror awaited them - a gauntlet

of lead and fire.

"They just kept shooting and shooting and shooting,"

sobbed a woman named Raisa Aslanova. She said her husband and

son-in-law were killed right in front of her eyes. Her daughter

was still missing.

Scores, hundreds, possibly even a thousand had been slaughtered

in a turkey-shoot of civilians and their handful of defenders.

Aside from counting every corpse, there was no way to tell how

many had died. Most of the bodies remained inaccessible, in the

no-man's land between the lines that had become a killing zone

and a picnic for crows.

One thousand slaughtered in a single night? It seemed impossible.

But when we began cross-referencing, the wild claims about the

extent of the killing began to look all too true. The local religious

leader in Aghdam, Imam Sadigh Sadighov, broke down in tears as

he tallied the names of the registered dead on an abacus. There

were 477 that day, but the number did not include those missing

and presumed dead, nor those victims whose entire families had

been wiped out and thus had no one to register them. The number

477 represented only the number of confirmed dead by the survivors

who had managed to reach Aghdam and were physically able to fulfill,

however imperfectly, the Muslim practice of burying the dead

within 24 hours.

Elif Kaban of Reuters was stunned into giddiness. My wife, Hijran,

was numb. Photographer Oleg Litvin fell into a catatonic state

and would only shoot pictures when I pushed him in front of the

subject: corpses, graves, and the wailing women who were gouging

their cheeks with their nails. The job required stomach. Now

was the time to work - to document and report: a massacre had

occurred, and the world had to know about it.

We scoured the town, stopping repeatedly at the hospital, the

morgue and the ever-growing graveyards. We moved out to the edges

of the defensive perimeter to meet the straggling survivors stumbling

in. Then we would rush back to the hospital to check on those

recently admitted who had been wounded. Then back to the morgue

to witness truckloads of bodies being brought in for identification

and ritual washing before burial.

I searched for familiar faces and thought I saw some but could

not be sure. One corpse was identified as a young veterinarian

who had been shot through the eyes at point-blank range. I tried

to remember if I had ever met him, but could never be sure. Other

bodies, stiffened by rigor mortis, seemed to speak of execution:

with their arms thrown up as if in permanent surrender. A number

of heads lacked hair, as if the corpses had been scalped. It

was not a pretty day.

Toward late afternoon, someone mentioned that a military helicopter

on loan from the Russian garrison at Ganja would be making a

flight over the killing fields, and so we traveled out to the

airport. No flight materialized, but I did find old friends.

"Thomas," a man in military uniform gasped, and grabbed

me in an embrace, and began weeping, "Nash Nachalnik..."

[Our Commander]

I recognized him as one of Arif Hajiyev's boys, a pimply-faced

boy from Baku who had described himself as a banker before he

had volunteered for duty in Karabakh. He was speaking in Russian,

babbling, but I managed to understand one word above his sobs:

the commander...

A few other survivors from the Khojali garrison stumbled over

to me. Of the men under Arif Hajiyev's command, only 10 had survived.

Dirty, exhausted and overcome with what can only be described

as survivor's guilt, they pieced together what had happened during

that awful night and the following day. Their commander - Arif

Hajiyev - had been killed by a bullet to his brain while defending

the women and children. And about the women and children - most

of them had died, too.

***

Towards evening, we returned to the government guesthouse in

the middle of town searching for a telephone. There we met an

exhausted Tamerlan Garayev. A native of Aghdam, the Deputy Speaker

of Parliament was one of the few government officials of any

sort that I found there. Tamerlan was interrogating two Turkmen

deserters from the Stepanakert-based 366th Motorized Infantry

Brigade of the Russian Interior Ministry forces that had descended

on Khojali the week before. The last missing link of the tragedy

suddenly fit into place: not only had the doomed town been assaulted

by the Armenians, but the Russians had been undeniably involved

as well.

"Talk, talk!" Tamerlan demanded, as the two men stared

at us.

"We ran away because the Armenian and Russian officers were

beating us because we were Muslims," one of the men, named

Agha Mohammad Mutif, explained. "We just wanted to return

home to Turkmenistan."

"Then what happened?" Tamerlan wanted to know.

"Then they attacked the town," the other explained.

"We recognized vehicles from our unit."

The two had tried to flee along with everyone else in town and

were helping a group of women and children escape through the

mountains when they were discovered by the Armenians and the

366th.

"They opened fire and at least twelve men in our group were

killed," Mutif recounted. "After that, we just ran

and ran."

Could such a thing have really happened: a Russian-backed assault

by Armenians on an Azeri town, which resulted in up to 1,000

dead?

This was news. But as we started to file our stories, we became

aware of something very strange. No one seemed interested in

the story. Apparently, the idea that the roles of the good guys

had been reversed was too much: Armenians slaughtering Azeris?

"You're suggesting that more people died in this single

attack in Karabakh than the total number that we have reported

killed over the past four years?" observed BBC's Moscow

correspondent when I tipped him on the bloodbath.

"That's impossible," he replied.

"Take a look at Reuters!"

"There's nothing on the wire."

Indeed, there wasn't. Although Elif Kaban had been churning out

copy on her portable Telex, nothing was appearing on the wires.

Either someone was spiking her copy, or was rolling it into a

larger, anodyne regional report of "conflicting allegations".

To be fair, the government and press in Baku didn't exactly assist

our efforts to get the story out. While we had been off in Aghdam

trying to break the news, the presidential spokesman was claiming

that Khojali's feisty defenders had beaten back an Armenian attack

and that the Azeris had suffered only two casualties. They were

pitching it as just an ordinary night in Mountainous Karabakh.

We knew differently, but it was the three of us against the Azerbaijani

State propaganda machine.

Finally, I managed to get a call through to the Moscow Bureau

of the Washington Post and told them that I wanted to file a

story. The staffers said they were too busy to take a dictation.

When I insisted, they reluctantly patched me through to the Foreign

Desk in Washington. I used the number of 477 people to indicate

how many had died. After all, that was the figure that had been

so carefully determined by Imam Sadighov. Though the figure turned

out to be low, the editors "dragged me over the coals."

Where had I gotten such a figure, since Baku was reporting that

only two people had died? Had I seen all the bodies? They cautioned

balance. Besides, the Armenian press was reporting that there

had been a "massive Azeri offensive."

"Why wasn't that in my report?" The editors wanted

to know.

I was about to defend my position that I had not written such

because it simply had not happened when suddenly the first of

many Kristal missiles started raining down on Aghdam and landing

only about a mile away from the Government Guest House that I

was calling from. Other missiles followed, and when one crashed

into the building next door and blew out all the windows in our

building, we thought it best to get down to the basement before

we were blown to smithereens.

An hour later, crawling out from under the mattresses, we came

up for air and decided we had better get out of Aghdam as fast

as possible. About 60,000 other people had the same idea, and

we suddenly found ourselves in the middle of a mass exodus of

trucks, cars, horses and people on bicycles, all rushing to flee

east in the direction of Baku.

***

I broke the news about the Khojali massacre with a world-exclusive

story on February 27th. It made an inside page of the Washington

Post. London's Sunday Times took the story more seriously - maybe

because they were Europe - and gave it front-page coverage. By

then, the international hack-pack had started parachuting in

to count bodies and confirm that something awful had really happened.

The first Western reporter who managed to arrive in the killing

fields and perform the grisly task of counting the dead was Anatol

Lieven of the London Times. His companion was the late Rory Peck

of Frontline News - another cool professional and dear friend.

[Less than two years later, Rory would be shot to death in front

of Ostankino TV in Moscow on October 3, 1993, when Boris Yeltsin

decided to restore democracy in Russia through the barrels of

guns.]

Others performed less well. One reporter from Agence France-Press,

best left nameless, arrived in Aghdam the night we left and found

the city "quiet," apparently confusing the silence

that followed the missile-induced exodus of 60,000 people with

an aura of peace and tranquility.

The government of Azerbaijan, meanwhile, made a complete about-face

on the issue. The same people who had remained inaccessible during

the early days of the crisis were suddenly asking me to provide

telephone numbers of foreign correspondents in Moscow whom they

could invite down - at government expense - to report on the

massacre.

That didn't set well with me. I almost hauled off and assaulted

the Presidential Press Secretary, accusing him of lying. He,

in turn, started a rumor that I was an Armenian spy sent to Khojali

to ferret out "military secrets" during my January

visit to the doomed town. Consequence: I was temporally detained,

causing me to slide into a very black mood. When I was released,

I went downtown and found myself sitting at a shop with a bunch

of black marketeers, who were vaguely waiting for me to exchange

my dollars for rubles. Then the whole situation hit me and hit

me hard.

The evening streets were still filled with light-hearted shoppers,

apparently oblivious or, perhaps, indifferent to the fate of

the citizens of Khojali. The men seemed to be all look-alikes

in leather jackets, and the women had far too much rouge on their

cheeks. They were all smiling and laughing and parading around.

I have to confess: I hated every one of them. Maybe they didn't

know what I had done. Maybe they did know but didn't care, lest

it drive them insane. It wasn't clear, nor was my brain.

I canceled the dollar deal, walked out of the shop and wandered

the streets. I think it was raining, but I can't remember for

sure. I meandered the streets, unable to stop anywhere or see

or talk to anyone for hours and hours.

"Ha ha," someone cackled, as he leaned toward his sweetheart

and switched on the motor of his car.

"Ho ho," another chortled, as he lurched out of a "Komisyon"

shop, a bottle of Finnish vodka under arm.

I wanted to slash their tires, smash their noses, burn their

houses. I wanted to do something - something violent. Instead,

I ended up wandering the streets in a daze. Finally, I arrived

home and sat down and poured myself a long drink. Hijran asked

me where I'd been.

"Khojali," I answered in a voice that I didn't recognize.

I had been in that dump of a town with ghosts and no food to

speak of, no water to wash with. And all the people from there

that I had known were dead, dead, dead. I broke down and cried

and cried and criedvowing that I would remember Commander Arif

and all the others, whose names I had never known, but whose

faces would be etched forever in my memory.

____

Back to Index

AI 10.1 (Spring 2002)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|