|

Spring 2002 (10.1)

Pages

32-35

A Moment's Warmth

In a

Forgotten Land

by Kathy Lally, photography

by Algerina Perna, both of The Baltimore Sun

Reprinted with permission from The Baltimore Sun, December

23, 2001.

Gift From Afar: Caring Shared,

Square by Square - Lisa Pollak

The little crowd presses close to the

man with the list. He calls out the first name and a frisson

of eagerness, of expectation and even hope roils from one to

another, women wearing layers of mismatched castoffs, men in

tattered caps and suits worn long past respectability, children

in anything that fits. The little crowd presses close to the

man with the list. He calls out the first name and a frisson

of eagerness, of expectation and even hope roils from one to

another, women wearing layers of mismatched castoffs, men in

tattered caps and suits worn long past respectability, children

in anything that fits.

They reach up in desperation and yearning.

The long journey is at an end. Some of the quilts stitched in

Perry Hall by the women of St. Michael Lutheran Church have reached

their destination, 7,000 miles away, in the Muslim country of

Azerbaijan. Shipped from Baltimore along with quilts from other

U.S. churches, trucked to a United Nations warehouse in the capital

of Baku, they have been driven to refugee settlements: in Saatli,

where many of the 50,000 refugees who live in drafty railroad

boxcars are encamped, and to Vagazin, where a few hundred others

live in snake-infested underground holes, and to Agjabedi, where

400 more live in an abandoned hostel with sporadic electricity

and no running water.

The refugees clutch piles of three and four quilts as if they

will bring deliverance. Someone has thought of them, has sent

them something to help, a bit of warmth for the spirit as well

as the flesh.

Left: Each family uses three boxcars: one as a kitchen;

one as the foyer; and one as a bedroom/living room. Left: Each family uses three boxcars: one as a kitchen;

one as the foyer; and one as a bedroom/living room.

But then the attention

delivered with the quilts is over. The empty truck pulls away.

And once again these are a forgotten people, a virtual city of

forgotten people, 570,000 of them scattered around the country.

Quilts cannot offer a way out of desperation. They cannot suggest

peace with Armenia, or promise a return to the homes and lives

abandoned eight years ago when the war began. They do not bring

the prospect of jobs, or decent clothing for the children, or

any kind of future at all.

"I don't need aid", says Valida Gasimova, a retired

teacher in Agjabedi. "I need my own land back." The

women gather around her, telling of sick husbands and daughters,

of the shame of surviving on handouts when they could work if

only they had jobs, how their teenagers suffer bitterly for lack

of decent clothes, how their small children go without toys.

But they are a sturdy people, and they are as ashamed of complaining

as they are of their circumstances.

"We are refugees," says Gulchohra Taghiyeva, a 45-year-old

former school librarian, "and we are very grateful for everything

you send us.

"We have stopped complaining," she says. "Just

don't pay any attention to that."

They are country women, favoring long dresses or skirts and brightly

colored kerchiefs on their heads. Taghiyeva wears what has been

given to her despite the incongruity - a tracksuit jacket over

a leopard-print dress. She insists that any visitors here must

come to her home for tea, and if they refuse she will be mortified

forever.

Above:

One day in 1993, the freight

trains stopped running through the Azerbaijan town of Saatli

because their destinations had been captured by Armenia in the

war over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Soon, displaced people

on the run filled up the boxcars that once held animals and grain.

Somehow, they live their lives here, even cooking the large flat

rounds of bread on outdoor fires built between the rails. Children

like Elman Mammadov (left) have no toys and little to do. He

sits as bread is being prepared by (from left) Elmira Guliyeva,

Filyar Mammadguliyeva and Kamala Mammadguliyeva.

Left: The talented hands of 70-year-old Afarin Abdullayeva

have produced rugs and quilts and needlepoint and embroidery.

On this day, they clutch a gift (left), a patchwork quilt from

Maryland, and some of her own work (right). Left: The talented hands of 70-year-old Afarin Abdullayeva

have produced rugs and quilts and needlepoint and embroidery.

On this day, they clutch a gift (left), a patchwork quilt from

Maryland, and some of her own work (right).

She leads her new American

friends to the five-story hostel, where the hallways are long

and very dark, and children emerge from the apartments like rabbits

bounding out of a cramped hutch. Her family of six lives in two

rooms. Often, they go for three days without water, which they

haul from a tap outside the building when it's running.

Taghiyeva walks to a nearby river to wash clothes; she cooks

on a hotplate and bakes bread in an outdoor oven. A group of

families built an outhouse, their only convenience.

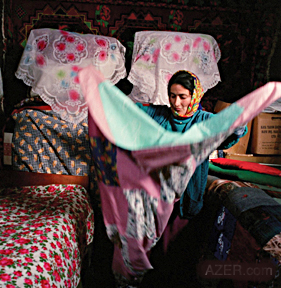

Though Taghiyeva's two rooms are damp and dark, treasures lie

inside. At the expense of medicine for her husband and clothes

for herself, she has sewn a dowry for her 22-year-old daughter:

more than a dozen thick quilts.

"I'm proudest of these," she says, lovingly stroking

two in red velveteen and another in green. "I sew with my

daughters. It's our tradition. All the things we were preparing

for my son, we left behind. We were building him a house, so

he could marry. That's gone. But I have a dowry for my daughter."

Eight more dowry quilts are airing outside,

waving on a clothesline like sunny flags of defiance, testament

to Gulchohra Taghiyeva's refusal to surrender to circumstances. Eight more dowry quilts are airing outside,

waving on a clothesline like sunny flags of defiance, testament

to Gulchohra Taghiyeva's refusal to surrender to circumstances.

These rural people cherish their bedding. When they fled their

homes, it was their quilts they gathered up as they ran.

Right: A refugee woman sits under an abandoned

boxcar, the only place the refugees in Saatli can now call home.

In the countryside of Azerbaijan, a woman's reputation could

stand or fall on the plumpness of her pillows and the elegance

of her quilts, and her handwork provided a rich vein of conversation

for neighbors and relatives to mine.

At night, pallets were put out on the living room floor for sleeping.

Mornings, they were folded up with the colorful quilts, stacked

in the living room under a crown of pillows and covered with

a veil of white lace, a still life ready for any neighbor's appraising

gaze.

Left: Once Filyar Mammadguliyeva, 32, (left) and Kamala

Mammadguliyeva, 25, had little stone houses surrounded by trees.

War destroyed it all. Now they walk along railroad ties instead

of garden paths. They are carrying quilts, made by Lutheran women

in America and distributed here by the United Nations High Commissioner

for Refugees. Though the women all pride themselves on their

own beautifully handmade quilts, the arrival of the gifts connects

them, for a moment, to the wider world, which otherwise ignores

them and their desperate desire to return home. Left: Once Filyar Mammadguliyeva, 32, (left) and Kamala

Mammadguliyeva, 25, had little stone houses surrounded by trees.

War destroyed it all. Now they walk along railroad ties instead

of garden paths. They are carrying quilts, made by Lutheran women

in America and distributed here by the United Nations High Commissioner

for Refugees. Though the women all pride themselves on their

own beautifully handmade quilts, the arrival of the gifts connects

them, for a moment, to the wider world, which otherwise ignores

them and their desperate desire to return home.

The wool in the pallets

and quilts and the down in the pillows came from the sheep and

geese the women tended, and a fat pillow was evidence of her

talent and hard work.

They have clung to their quilts as if even one small thread from

their pasts will bind them together, protect them and preserve

the promise of their return home.

We love beautiful quilts and pillows," Taghiyeva says.

Kind hands in far-off Maryland have sent quilts here. Capable

hands made idle and desperate have received them.

But the hands here remain outstretched, awaiting something more

than hope.

____

Back to Index

AI 10.1 (Spring 2002)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|