|

by Brita Asbrink

Other articles related to the Nobel Brothers: (1) Legacy of the Oil Barons:

The Nobel

Brothers' "Greening" of Baku by Fuad Akhundov (AI

2.3, Autumn 1994) Back in 1996, as I was preparing

for an assignment with the International Federation of the Red

Cross/Red Crescent in the Caucasus, someone mentioned to me:

"Oh, by the way, the Nobel brothers produced oil in Baku,

did you know that?"

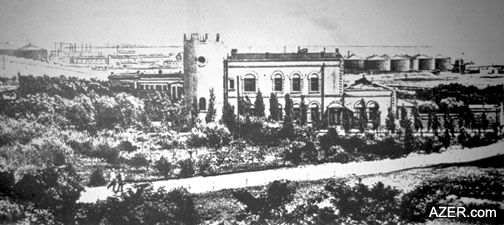

Above, left to right: Logo of Nobel Brothers'Petroleum Company, depicting the Fire-Worshippers' Temple in Surakhani near their oil fields. Nobel Brothers - Alfred, Ludvig and Robert. Early on during my stay in Baku, I made a trip to the Black City district of Baku to see what was left of the Nobel residence - Villa Petrolea. After all these years, the main building is still standing, though derelict and in desperate need of restoration. A residential block building, once used as dormitories, stands neglected. The other buildings on the compound were demolished long ago. The theater and clubhouse have burned down. A park was established in the front expanse of yard that extends down to the sea. It's said that more than 80,000 plants were planted on the grounds, having been brought in on ships from the southern regions of Azerbaijan along with the rich soil and water.  I also walked around the heart of Baku, marveling at the magnificent mansions that had been built during the city's first Oil Boom and learning about how the oil barons cooperated and competed with the Nobels. German Church In March 1999, the German Lutheran Church in Baku celebrated its 100th Jubilee. It was there that I met Carl Tydén, who had flown in from Sweden specifically for the celebration. Tydén was responsible for maintaining the Archives of the Nobel Family Association in Stockholm. It was his first trip to Baku. One photo that I later came across shows members of the Nobel Family laying the foundation stone for Baku's German Lutheran Church. The date was April 21, 1896 (May 3, according to the old calendar). In order to have their own Protestant place of worship in Baku, the Nobels helped finance nearly 50 percent of the construction of this church. The church is still familiarly known around town as the "Kirche". It was one of the few places of worship that was not demolished during Stalin's era. But since the Soviet period, its primary use has been for concerts. The Hall houses one of the city's two pipe organs (the other being at the Academy of Music) and offers excellent acoustics for chamber and symphonic orchestra concerts. Sunday Mass is offered each Sunday for about two hours. About 100 people attend. Below, right: Azerbaijani women walking along Czar Nicolas Street in front of Baku's City Hall, late 1800s. Women wore chadors (veils), traditional Islamic public attire, which was banned in the late 1920s by the Soviet regime. Photo: Asbrink Collection.  As the 100th Jubilee of the first Nobel Prize approached (2001), Swedes started contacting the Nobel Foundation about their private collections of letters, photos and diaries that had once belonged to the grandfathers and fathers who had worked for the Nobel Brothers in Baku or Russia. Carl Tydén generously offered me access to all of this information along with the Nobel family archive. Voices From the Past As I started delving into the material, I tried to imagine what life must have been like for the Nobels in Baku. Although they made their home in St. Petersburg, they occasionally went to Baku for work or pleasure, staying for a few months each time. During their stays, they often went with their employees on excursions throughout Azerbaijan, visiting local farms and villages and sailing on the Caspian. They enjoyed watching the phenomenon of fires seemingly floating on the surface of the water, which could be seen at that time. They visited Azerbaijan's mud volcanoes and ancient fire-worshipping temples.  Impressions and stories of daily life were deposited in Carl Tydén's archives, including the Nobel family's correspondence between Baku and Sweden and Finland. Interspersed among the everyday concerns is some interesting anecdotal material about Azerbaijan. For instance, in one letter, a young woman named Ruth remarked on the beautiful dark eyes of Azerbaijani men. "One may not gaze into them too deeply," she cautions. As may be expected, living abroad created certain dilemmas for the Nobels and expatriates. "What should I bring home as a souvenir? Carpets?" one person wondered. "How can I get through customs without paying extra for my medicine? How do I communicate with the shopkeepers? How do I give directions to the driver?" Other letters mention the trials and difficulties of hiring and managing much-needed domestic help. Sometimes the maids and cook are described as being lovely to have as helping hands in the household; at other times, they are accused of stealing, drinking and mismanaging household affairs. Some wondered why the mail to Europe was so slow. Others were concerned about ill children or a husband fighting diabetes. Research is a fascinating thing - one discovery leads to another. It was thrilling to read those old letters, memoirs and diaries. Before long, I could look at a photo and begin to identify some of the people in it, connecting the photo to a specific event. Unfortunately most photos lack captions and necessary documentation about the people, place or date, so I've had to make a lot of educated guesses. In my book, I've cited complete letters written by members of the Nobel family and added large sections of memories written by staff and their family members as found in diaries and letters. Prior to this, such information was really not available. Though others have written about the oil business, such as the yearly production in numbers of barrels, I have placed my emphasis on personal relations, the thoughts and feelings that reflect the events of personal life and politics. Below: A group of Nobel employees and their wives and children visiting Mr. Ashorbshoff (the man smoking the water pipe) on October 24, 1909. Bottom: Brita Asbrink's book, "Ludvig Nobel: 'Petroleum Has a Bright Future!" Photo: Asbrink Collection.  Actually, he never fully understood the ups and downs of the oil business. Family members basically wrote to one another in Swedish, but you can find letters written in Russian, English, German and French. Most people think of Alfred as being immersed in his work as it related to dynamite and explosives. But the truth is that he was closely involved with oil production up until his death in 1896. Ludvig's son Emanuel bought Alfred's shares, thus enabling Alfred to establish the Nobel Prize with the proceeds along with his earnings related to dynamite. In the past, Alfred has often been pictured as being lonely, unhappy and isolated. But from reading his letters, I would suggest this is not quite true. Alfred was part of a clan, in constant contact with his mother, his brothers and nephews as well as with intellectuals and inventors, despite extensive traveling and problematic business investments.  It might be interesting to note that Alfred refused to visit Baku; he was convinced the city was dry and dusty. However, Ludvig's second son, Carl, was very comfortable in Baku and praised the country and its people. He wrote that he enjoyed buying bread and grapes from vendors in the streets. Up until the Revolution (1918), the visiting Nobels and their employees lacked for nothing. They enjoyed Azerbaijan's caviar, champagne, tea, meat, fish, fruits and berries. One particular harvest from the garden of Villa Petrolea brought in buckets of peaches. End of an Era The Nobels were pioneers who worked hard to fulfill their ideas and visions for the company. While they worked intently to solve the technical and logistical problems that came up, it seems they were quite oblivious to the region's social and ethnic unrest, which would eventually lead to a revolution. At the beginning of the 20th century, political turbulence among the Caucasus' poor and unskilled laborers manifested itself in political strikes, robberies and murders. As agitators such as Koba [Stalin] held secret meetings in the workshops and oil fields, criminal gangs kidnapped and robbed the rich to "sponsor" these political activities. At the time, Russia was in turmoil, and the war with Japan was having a devastating effect. Ethnic conflict spread throughout the Caucasus. In 1907, four of the Swedes who worked for the Nobel company were murdered. Anders Tauson, Gustaf Adolf Packendorff and two others by the names of Lotberg and Anderson were killed. It's thought that Tauson, head of the Mechanical Workshop in Baku, may have been targeted because he had refused to give the workers piecework, which possibly would have increased their pay. After this incident, some other foreigners opted to leave Baku, fearing for their own safety. By 1918, the Nobel family had partly fled to Stockholm, having lost all of their Russian assets to the Bolsheviks. As they had no more oil for their European partners, they sold the companies that they still owned in Europe. The Red Army entered Baku in April 1920. A few months later, during the Great Depression, half of the Nobel's oil company shares were sold to Standard Oil in New Jersey, a masterstroke negotiated in New York by Gösta Nobel, Ludvig's youngest son. And the family's economic future was secured. Book and Documentary My book about the Nobels was published in Sweden in November 2001, prior to the 100th anniversary of the first Nobel Prize. The book's title is based on a quotation from a letter that Ludvig wrote in 1864 to his brother Robert: "Ludvig Nobel: 'Petroleum Has a Bright Future' - A History of Inflammable Oil and Revolution in Baku." The book covers the Nobel brothers and the oil company they created in the 1870s, with photographs from private collections and public archives. While the main subject is the oil business in Baku and the Nobels' competition with Standard Oil, Rothschilds and Royal Dutch/Shell, I also give a picture of how Russian politics influenced events of the time. In addition, I produced a TV documentary, "Red Sun Over the Nobel Oil Fields," which aired on Swedish TV shortly before the Nobel Prize celebration held on December 10, 2001. The documentary was one of a series of programs about Alfred Nobel, concerning the disciplines he felt would bring peace and prosperity to humankind. Alfred was a true internationalist who kept himself informed about the developments in science and the discussions being held in intellectual circles, especially those related to the preservation of peace. While Alfred himself never visited Azerbaijan, he was very involved with the company's affairs for 16 years, and consulted with his brothers by mail on financial, chemical and technical matters. Up until now, his involvement with the oil-producing company has never really been fully explored. The Nobel Foundation has tended to focus on his various other undertakings, especially his inventions related to dynamite and explosives. There's still a lot to be learned about the Nobel family. For example, I would love to exhibit the collected photos in Baku and show the TV documentary in Azerbaijan. In the meantime, I am part of a group of researchers working to compile the documents of Alfred and his family from 1650 to 1930. Our plan is to make this information available for future research on the Internet. Brita Asbrink is a freelance

writer based in Stockholm, Sweden. Contact: brita.asbrink@chello.se.

To order her book, "Ludvig Nobel: 'Petroleum Has a Bright

Future!'" (Ludvig Nobel: "Petroleum har en lysande

framtid!"), contact her publisher, Wahlström &

Widstrand, Sturegatan 32, s-114 85 Stockholm, Sweden. Tel: (46-8)

696 84-80; Fax: (46-8) 696 83-80; info@wwd.se;

www.wwd.se. The text is written

in Swedish, but there are plans for it to be translated into

Russian for the 300th anniversary of St. Petersburg, to be celebrated

in 2003. It is lavishly illustrated with well-chosen photos. Back to Index

AI 10.2 (Summer 2002) |