|

Summer 2002 (10.2)

Page

53

Water - Not a Drop to Drink

How Baku

Got Its Water-The British Link - William H. Lindley

by Ryszard Zelichowski

Oil was also behind Baku's effort to

develop an infrastructure related to water distribution. By the

late 19th century, Baku's city planners had long been faced with

a dire issue: water shortage. They were desperate to find a reliable,

healthy source of water. The problem reached critical proportions

by the mid-1800s and by the time the Oil Boom began in the 1870s,

Baku had exhausted all known solutions, from channeling water

from nearby rivers to building desalination plants. Finally,

they sought international expertise and, after years of research

and deliberation, the decision was made to bring water from the

faraway foothills of the Caucasus Mountains. Oil was also behind Baku's effort to

develop an infrastructure related to water distribution. By the

late 19th century, Baku's city planners had long been faced with

a dire issue: water shortage. They were desperate to find a reliable,

healthy source of water. The problem reached critical proportions

by the mid-1800s and by the time the Oil Boom began in the 1870s,

Baku had exhausted all known solutions, from channeling water

from nearby rivers to building desalination plants. Finally,

they sought international expertise and, after years of research

and deliberation, the decision was made to bring water from the

faraway foothills of the Caucasus Mountains.

British civil engineer William Heerlein Lindley (1853-1917) coordinated

the project for Baku's water supply system, working from 1899

up until his death in 1917. Having designed many of the water

systems in Europe, he calculated that springs located high up

in the Caucasus would provide a plentiful amount of water for

Baku and its residents. He attempted something that had never

been done before, not even in Europe. He constructed a pipeline,

originating at the water source in the Caucasus mountains and

extending 110 miles (177 km) south to Baku. It was the right

decision. Even today, the Shollar pipeline remains vital to central

Baku's water supply and is considered the most reliable, healthy

source in the entire city.

Above: Vendors selling water in the streets

of Baku. Early 1900s.

Dr. Ryszard Zelichowski, a Polish historian, was researching

the relationship between hygiene and city engineering in 19th-century

Warsaw when he discovered that the major water supply and sewage

systems had been designed by British engineer William Lindley

(1808-1900). Through extensive research, he learned of the eldest

son's connection with waterworks in Baku.

Left: Water vendors in Baku's streets before Shollar

Water system was installed in 1917. Left: Water vendors in Baku's streets before Shollar

Water system was installed in 1917.

Zelichowski's study

is, in fact, part of a growing body of literature referred to

as "Euro-Biography". His research identifies two major

trends in Victorian engineering: (1) the incredible progress

made by Western civilization, thanks to the ingenuity of these

engineers in designing filtration systems for drinking water

and in creating indoor plumbing, and (2) the profound legacy

of these engineers as the first "true" Europeans who

became deeply engaged in multiculturalism for the benefit of

the entire region. In today's lingo, we might have called them

"Engineers Without Borders".

Here Zelichowski describes Baku's struggles to find a reliable,

sufficient water supply, which Lindley himself described as "one

of the most challenging projects he ever undertook in his entire

life."

______

On January 28, 1899, the Baku

Commission for Water Supply informed the provincial Baku Duma

(Russian for "parliament") that it was seeking a project

to provide a sewage and water supply system for the city. This

water supply system would use the vast resources of water from

the Samur and Kur rivers, enough to supply the city with 3 million

buckets of water per day.

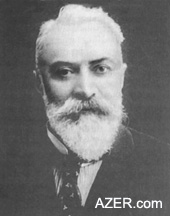

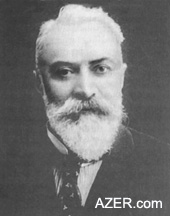

Left: Sir William H. Lindley. Left: Sir William H. Lindley.

With that goal in mind,

the Commission applied to three different European civil engineers;

one of them was William Heerlein Lindley (1853-1917). Lindley

and his family were known throughout Europe for their feats of

civil engineering. After beginning their activities in Germany,

they had expanded to more than 30 cities in Central and Eastern

Europe.

Lindley responded to the Duma's letter on June 3, 1899. Accepting

his conditions, the Duma sent a cable inviting him to come to

Baku as soon as possible. Lindley arrived in October and stayed

there for two months.

During his visit, he went to the countryside to examine the geological

structure of the surroundings of Baku. He found that the Kur

River had the best water resources and was most suitable for

supplying the city. Unfortunately, it was 120 km from Baku, in

land that was densely populated. A project that connected to

the Kur River would require a sophisticated, expensive system

for transporting and filtering the water.

Shollar Springs

When Lindley reported his findings to the Duma on December 18,

1899, he suggested the possibility of getting water from the

Caucasus mountains, especially the area of the Gusar river and

the Gil forest. Assisted by a detachment of Cossacks, he had

visited two springs called Shollar and Fersali. There he had

found a large quantity of pure water that would meet the current,

and, what he thought would be the future, needs of Baku. Since

the springs originated at a high elevation, the water could flow

for 40 km due to the sheer force of gravity.

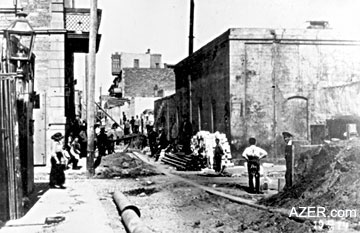

Right: Shollar Water Early 1900s. Above: Laying

of the water pipes through Balakhan (now Fizuli) street. Right: Shollar Water Early 1900s. Above: Laying

of the water pipes through Balakhan (now Fizuli) street.

Lindley's next visit to Baku was in May 1901. After a well-prepared,

professional lecture to the members of Duma, he convinced the

government to let him proceed with the project.

On June 23, 1901, the contract was ratified. For the entire design

and execution of the waterworks, Lindley was offered the handsome

sum of 35,000 rubles. Of this amount, 25,000 rubles had been

offered by Azerbaijani oil baron and philanthropist Haji Zeynalabdin

Taghiyev (1823-1924).

Lindley's project was scheduled to begin on January 1, 1902.

In the meantime, city mayor A. I. Novikov embarked on a long

journey to Western Europe to visit the water supply enterprise

in Frankfurt, Germany, which had been designed and supervised

by Lindley and his father, William Lindley (1808-1900). After

visiting the water plant, Novikov became a strong admirer of

the spring intake. When he returned to Baku, he insisted that

Lindley include both underground and spring intakes in his water

supply project.

Left: Surakhan (now Dilara Aliyeva) Street. Left: Surakhan (now Dilara Aliyeva) Street.

By the autumn of 1903,

two of Lindley's representatives had arrived in Baku with the

plans for the final project in their hands. The pipeline would

tap the Kur and Samur rivers, with intakes located at a distance

of 125 and 170 km from Baku. Formalities concerning the contract

were completed on October 23 that year. Drilling works were assigned

to a French company, under Lindley's supervision. At last, the

real work began on January 3, 1904.

Revolution Slows

Work

The revolutionary events in Russia (1905-1907) had a negative

impact on the waterworks project in Baku, causing it to be delayed.

This revolution is often recognized as the first revolution of

the industrial era in Europe. It began on the so-called "Bloody

Sunday" in St. Petersburg (January 22, 1905) and resulted

in a wave of solidarity strikes sweeping through the industrial

regions of the Empire. The impact was not felt in Baku until

1906, when the second wave of revolutionary action by soldiers

and sailors took place. These events in June 1907 let to the

dissolution of Russia's Second State Duma.

At the time, the Duma journal "Izvestia Bakinskoy Gorodskoy

Dumy" stated: "The bloody events in Baku entirely paralyzed

the economy, stopping work on the city's water supply."

Only after N. V. Rayevsky was appointed as the new city leader

in 1908 was Lindley able to resume work once again.

In the meantime, Baku's problems grew

more acute. Outbursts of cholera in 1907, 1908, 1909 and 1910

spread fear among the populace. These outbreaks were related

to the poor quality of the water supply and sewage system. Baku

residents had even developed two different words for good water

and bad water. Lindley reported that they called the impure water

"gara su" (literally, black water) and the pure water

"agh su" (white water). In the meantime, Baku's problems grew

more acute. Outbursts of cholera in 1907, 1908, 1909 and 1910

spread fear among the populace. These outbreaks were related

to the poor quality of the water supply and sewage system. Baku

residents had even developed two different words for good water

and bad water. Lindley reported that they called the impure water

"gara su" (literally, black water) and the pure water

"agh su" (white water).

Biggest project

Lindley often spoke about the difficulties of fulfilling such

a major project to supply Baku with water. He is reported as

saying, "In Western Europe alone, I have carried out water-pipe

and sewerage constructions in 35 cities. But I have never had

to deal with a work of such technical grand scale and difficulty

as the construction of this water pipe."

Above:

Pipeline for Shollar Water

brought water from the Caucasus mountains, 170 km from Baku.

Made of porcelain, it was the longest water pipeline for its

time in Europe or Russia. Completed 1917.

The 1912 edition of Illustrated London News praised Lindley's

achievements in an article entitled, "Water for a Great

Oil City: Building the Longest Conduit in Europe": "The

construction of reservoirs and a conduit for the supply of water

to the city of Baku constitutes an engineering feat without parallel

not only in Russia but also in Europe. It is the scheme designed

by and being carried out under the direction of Sir William H.

Lindley, M.Inst.C.E., F.C.S., whose works during the last 40

years have made his name famous throughout almost every country

on the Continent.Construction of the Baku Waterworks will form

an engineering feat, consisting as it does of the making and

laying of a conduit over a distance of 110 miles (the longest

pipeline in Europe) at the hitherto unprecedented rate of one

mile per week. The pipeline will be large enough for a man to

walk through, and is guaranteed to convey 25 tons per meter,

as a minimum load."

Despite the onset of World War I, work on the pipeline continued.

The demand for water in the city grew steadily as well.

According to the Duma journal, Lindley paid his last visit to

Baku in January 1916. On January 18, he delivered a lecture on

the prospect of supplying the industrial regions of Binagadi

and Surakhani with water from the Shollar intake. During that

visit, the city of Baku granted him honorary citizenship. This

was the last document that confirms anything about the journey

of Sir William H. Lindley to what was then a remote part of the

Russian Empire. News from the frontlines, then the Bolshevik

Revolution, meant the end of the world that he knew. Lindley

passed away peacefully in December 1917, of a stroke, in his

home in London, at the age of 64. Today the Shollar water system

is still considered to be the best water source for central Baku

both because of its superior quality and dependability of distribution.

Dr. Ryszard Zelichowski is a

historian with the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish

Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, Poland. He has published a number

of articles and a book (in Polish) on the Lindley family's activities

in Warsaw and other countries. His most recent book is a 450-page

biography of the Lindleys, in Polish, focusing on three geographic

areas: England, Germany and the Russian Empire (including St.

Petersburg and Baku). Contact him via e-mail at rzeli@omega.isppan.waw.pl.

For more information about the Shollar water pipeline, see "Shollar

Water: A Century Later" in AI

7.3 (Autumn 1999). SEARCH at AZER.com.

____

Back to Index

AI 10.2 (Summer 2002)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

Right: Shollar Water Early 1900s. Above: Laying

of the water pipes through Balakhan (now Fizuli) street.

Right: Shollar Water Early 1900s. Above: Laying

of the water pipes through Balakhan (now Fizuli) street.