|

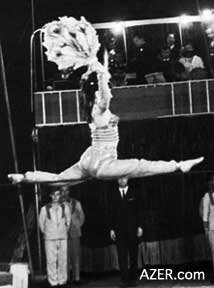

Above: (left) Shafiga performing with the Star Sisters in a show called, "Equilibrium". She was the first and only Azerbaijani (Muslim) woman to perform in the circus . Photo: 1940s. I was Azerbaijan's first and

only high wire dancer. I started out simply balancing on a wire

that was stretched two meters above the ground, but eventually

my act evolved to include performing traditional dances like

the fast-paced Lezginka.

Above left: Shafiga, doing the split on the high wire. Right: Usually Shafiga performed on the high wire, maintaining her balance with feathers, but later she began performing dances on the wire using a gaval (tambourine-like instrument) which because of its weight, she found much harder to balance with. 1950s-60s. The circus was scheduled to perform at the Decade of Azerbaijani Arts in Moscow, which was being organized by the famous composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov. I had a background in dance, so I decided to audition. They liked my performance and offered me the chance to perform with two other girls. We became known as the "Star Sisters" (Ulduz Bajilari), and our show was called "Equilibrium" (Ekvelibristika, in Russian). My mother strongly opposed the idea, but I didn't listen to her. I was going to Moscow, with or without her permission. She used to beat her head with her hands, saying it was impossible for an Azerbaijani girl to perform in the circus. My father wasn't there to stop me; he had died in 1942 while fighting in World War II. [More than 400,000 men from Azerbaijan never returned from the war.] In the end, Mother conceded and asked my teacher Yusif Aghayev to take good care of me. He promised that he would watch over me as if I were his own daughter. Most of the other performers were older circus professionals, so they didn't need to practice as much as we three newcomers did. It was difficult to prepare our act, which involved sitting, lying and standing on the high wire. Plus, we were only able to practice in the arena in the wee hours of the morning. The wrestling practice ended at midnight, then at 7 a.m., the animal trainers needed to use the arena. So we only had the hours between midnight and 7 a.m. to practice, only resting for an hour or two on the mattresses. We had to keep those crazy hours every night, to prepare ourselves. The training was very difficult and, yes, it was painful as well. I remember how the steel wire used to cut and bruise my skin. Even though we had special thick trousers to protect our bodies, I turned black and blue all over. I wore very thin leather slippers, not regular shoes, because I needed to feel the rope. As a result, the soles of my feet became very tough and calloused. Every day when I returned home from practice, I used to try to take away the stinging pain by bathing in salt solutions. Finally, after a great deal of training, I managed to develop quite a good sense of balance on the high wire. It requires incredible concentration. I used to choose a single focal point and then fully concentrate on that point, never letting my eyes wander anywhere else. The fact that the wire was only two meters off of the ground made it difficult, since there were always so many distractions as circus goers moved around in the arena. Sometimes it was extremely difficult to concentrate. We had a good team for our trip to Moscow in 1946. I was surrounded by a number of celebrities, such as producer Sultan Dadashov, ballet dancer Amina Dilbazi, painter Hasan Mustafayev and composers Sultan Hajibeyov, Niyazi and Rauf Hajiyev. When I signed up for the circus, I really had not intended to make a career of it. I figured that I would do it for a year, just to go and see Moscow. After that, I would return and continue my education in music. Little did I know that I would end up staying in the circus for another 30 years! I loved dancing, and I enjoyed traveling with the circus all over the former Soviet Union. I even married another circus performer. My late husband, Fikrat, and I traveled to so many places together. High-Wire Dances At first, my act involved balancing on the wire by holding onto a large feather. Later on, I tried to introduce something new, so I performed traditional dances like the Gulgaz and Gaytaghi. Rauf Hajiyev and Maestro Niyazi composed music for my dances. For one dance, I played a traditional instrument, the tambourine-like gaval. It was very difficult to do this. Holding onto the gaval pulled me down and made me lose my balance. But I managed to perform it. I also danced the Nalbaki, a unique dance that involves wearing thimbles on your fingers and clicking them against tea saucers. That was very difficult, too. Another act that I did involved pantomime, although not on the high wire. One of our stories told about a rebellion in a village. All of the peasants rose up against the local rulers. I was the hero. I was kidnapped and taken to the khan on a horse. So I had to practice riding horseback as well. I miss circus life. I got to visit all of the republics of the former Soviet Union and most of the major cities of Russia. People respected me so much there - they took care of me. When it was time for me to leave, they used to see me off with flowers. I also received honorary decrees from a number of cities in Russia. Now, however, to tell you the truth, I feel a bit forgotten and neglected. The government doesn't give me any special pension, as it does for some of the other performance artists. Still, I am grateful that the historians haven't forgotten me. Elchin Guliyev has made a film of my life. I was featured in the Encyclopedia of Azerbaijani Women, which was compiled by Sabir Ganjali in 2001. There was also a segment about my life on the show "Sabah" (Morning) on Space TV. Best of all, I have my memories of 30 years of experiences in the circus. ____ Back to Index

AI 10.3 (Autumn 2002) |