|

Autumn 2002 (10.3)

Pages

32-37

Art As Memory

Alakbar

Rezaguliyev's Prints of Azerbaijan

by Jean Patterson

To view other works of Alakbar Rezaguliyev, visit AZgallery.org

The

Prints of Alakbar Rezaguliyev

Life - more precisely, life under the Soviet system - was not

kind to artist Alakbar Rezaguliyev (1903-1974). During the Stalinist

repressions, Rezaguliyev was arrested three times for supposedly

spreading pan-Turkist ideas. Suffering the fate of thousands

of other intellectuals and creative geniuses, he spent the majority

of his adult life in prison and exile, nearly 25 years.

Perhaps the worst aspect of Rezaguliyev's sentence was the fact

that he was not allowed to pursue his dream of becoming an artist.

By the time he was free to return to Azerbaijan in 1956 after

Stalin had died, he was desperately out of practice, psychologically

broken and too weak even to hold a pencil.

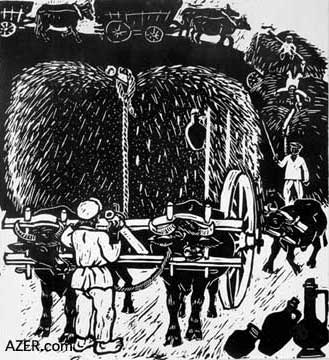

Left: Alakbar Rezaguliyev's linoleum prints,

"Kolkhoz Collects the Wool" (1966).

Right: "Gathering Hay" (1963).

Despite the odds, Rezaguliyev worked tenaciously to develop his

talent and make a name for himself. He became well known for

his art, especially for his remarkable series of black-and-white

linoleum prints depicting scenes from turn-of-the-century Baku.

Living so long inside those prison walls left its mark on Rezaguliyev's

works - but not as one might think. Most of his prints glorify

work, although not in a way that honors this labor for the sake

of production alone. Rather, the artist invites us to appreciate

the mundane, ordinary and sheer physical process of creating

with one's own hands and mind. Many of his prints depict workers

going about their everyday chores - shoeing water buffalo, loading

hay on wagons, making flatbread (lavash) or even slitting the

bellies of sturgeon to harvest caviar.

To gain insight into Rezaguliyev's tragic life and his motivations

for creating such nostalgic images, we turned to Rezaguliyev's

youngest son, artist Aydin Rezaguliyev, and the memories of the

artist's oldest daughter, the late Adila Rezaguliyeva.

______

Left: Alakbar Rezaguliyev's

print "Shoeing a Water Buffalo". Left: Alakbar Rezaguliyev's

print "Shoeing a Water Buffalo".

Alakbar Rezaguliyev

was born in Baku on January 31, 1903, into the large family of

a small businessman-shopkeeper. Although there were no artists

in his family, Rezaguliyev showed artistic talent at an early

age.

"When my father was a child," Rezaguliyev's son Aydin

retells, "his grandfather spoke with the akhund [local religious

authority]: 'Our little Alakbar draws pictures. What do you recommend?'

The akhund warned: 'Don't allow him to draw. It is forbidden

by God to draw pictures of human beings; it's a sin.'"

The akhund's words fell on deaf ears. Rezaguliyev went on to

study art at the Baku Art College just after it was established;

he graduated in 1922. He then pursued his passion for art in

Moscow at the Technical Art Studios School from 1925 to 1928.

Rezaguliyev supported the Communist Party when it was first established

in Azerbaijan in the early 1920s. In fact, he was part of that

first generation of "Komsomols" in Azerbaijan. Komsomols

were high school students who were on the path to becoming full-fledged

members of the Communist Party. Such a process usually started

for children in elementary school, who became "Octobrists";

older children became "Pioneers".

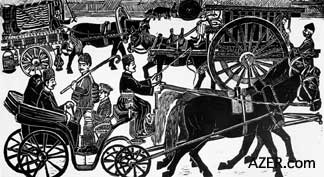

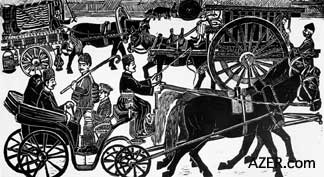

Left: Rezaguliyev's prints: Modes of transportation

in Old Baku at the turn of the 20th century. Below: "Wool

for Sale" (1963). Right: Crushing mulberries to make a thick

syrup. Left: Rezaguliyev's prints: Modes of transportation

in Old Baku at the turn of the 20th century. Below: "Wool

for Sale" (1963). Right: Crushing mulberries to make a thick

syrup.

Rezaguliyev's plan to

become a successful artist and a member of the Party was abruptly

halted in 1928. One of his friends, Ibrahim, was arrested for

spreading "pan-Turkist ideas." At that time, Stalin

and the other Soviet leaders were especially sensitive to the

possibility that Turkey could try to gain control over the Turkic

republics of the USSR. Turkic-speaking peoples lived in a wide

swath of territory along the Soviet southern flank and were united

by similar Turkic languages. These Turkic republics included

Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

Anyone who promoted unity amongst Turkey and the Turkic peoples

was targeted and accused of "pan-Turkism", an indictment

that often resulted in exile and death.

Since Rezaguliyev was associated with Ibrahim, he was arrested,

too, and sentenced to six years of exile in the freezing - cold,

sparsely inhabited region of Arkhangelsk in northwest Russia.

"I suspect that somebody falsely brought accusations against

my father," Aydin says. "After all, he was one of the

first Komsomols in Azerbaijan, he believed in the Communist system.

How could such a person turn around and curse the government?

It just didn't make sense. For sure, he was imprisoned without

any evidence."

During his exile,

Rezaguliyev underwent an arranged marriage. His father, mother

and future During his exile,

Rezaguliyev underwent an arranged marriage. His father, mother

and future mother-in-law somehow managed to bring

his bride, Sona, to him at Arkhangelsk. Sona lived with him there

for a while, then returned to Baku and gave birth to their daughter

Adila (1936-1997). mother-in-law somehow managed to bring

his bride, Sona, to him at Arkhangelsk. Sona lived with him there

for a while, then returned to Baku and gave birth to their daughter

Adila (1936-1997).

Exiled Again

After his release and return to Baku, Rezaguliyev ran into one

of the Bolshevik leaders, Ruhullah Akhundov, who was surprised

to see him out of prison. "Hey, you dumb guy, are you back

here again?" And with those words, he was promptly arrested

again and exiled to Solovki in the icy Arctic.

Right: Women's traditional

apparel, especially in some rural areas in the 19th century (1960).

"I was six months old in November 1937, when Father was

arrested," daughter Adila recalled on a television feature

about Rezaguliyev. "I didn't see him again until 10 years

later, in 1947. At that time when we met again, we didn't recognize

each other. Then he broke down and sobbed, saying that he was

so thankful to his parents for taking care of his keepsake for

all those years."

Between 1947 and 1949, Rezaguliyev and his family lived in the

northwestern regions of Azerbaijan. "The authorities wouldn't

let him live in Baku," Adila said. "We had to live

in Ganja and Shaki. I remember that he used to prepare sketches

for the silk factory in Shaki, where there was a large silk industry

at the time. He also taught school there.

"I remember one day when I was sitting with Father and Grandpa,

a rather handsome man by the name of Bahram dropped by. He was

the producer of the Ganja Theater. He fell to his knees in front

of Father and begged him: 'Forgive me for those years, for those

words.' My father didn't say anything and just turned his head

away. Grandpa said to Father: 'Alakbar, don't you see that he's

asking for your pardon?' Father answered: 'No, Dad, I can never

forgive him. For his lie, I had to spend nearly half of my life

in exile.'"

Left: "Long Live the Soviet Government"

(Azeri language in Arabic script): These three figures played

pivotal roles in the establishment of Soviet power in Azerbaijan:

Sergey Kirov (1886-1934), Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925) and Grigori

Orjonikidze (1886-1937). Ironically, under Stalin's authority,

they all became victims and were annihilated by the system they

helped to create. Left: "Long Live the Soviet Government"

(Azeri language in Arabic script): These three figures played

pivotal roles in the establishment of Soviet power in Azerbaijan:

Sergey Kirov (1886-1934), Nariman Narimanov (1870-1925) and Grigori

Orjonikidze (1886-1937). Ironically, under Stalin's authority,

they all became victims and were annihilated by the system they

helped to create.

In 1949, shortly after

his second daughter, Sevil, was born, Rezaguliyev was arrested

yet again and sent to the frigid Altai Province in northern Russia.

While in exile, he married again, this time to a German girl

named Berta, whose parents and grandparents had been living in

a German settlement in the Saratov Autonomous Region. At the

beginning of World War II, Berta's family had been sent into

exile, just like all of the other Germans who were living in

the USSR.

"I was the only one in the family who knew about Father's

second marriage," Adila confided. "He wrote me secretly

and asked me not to be angry with him for marrying again, that

he did it only to keep from dying of hunger and cold. He found

a warm home for himself by marrying that woman." Rezaguliyev

and Berta had two sons, Ogtay and Aydin, and a daughter, Sevda.

In 1956, three years after Stalin's death, Rezaguliyev was exonerated

and released from exile. Stalin's repressions were over.

By the early 1960s, Berta and her children were allowed to join

him in Azerbaijan. Aydin remembers the pressures of adjusting

to Baku and blending in with his father's existing family. "I

was in the second grade at the time, and I remember how difficult

it was for us when we came to Baku. We only knew how to speak

German - not Russian or Azeri. Slowly, things got better. We

lived in the Montin settlement, which is in the Narimanov district

of Baku."

Not surprisingly, those 25 years of exile had taken a serious

toll on Rezaguliyev's health. "When Father came back, his

hands were stiff," Adila recalled. "He had trouble

just holding a pencil."

"The exile greatly affected my father's personality,"

Aydin adds. "He became very serious. You can see it in his

photos: in the early ones, he was always smiling, but after he

was exiled - never. Being imprisoned all those years morally

broke him."

Eager to Work

Rezaguliyev threw himself into his art, working day and night

to develop his technique. "I remember my father would leave

the house each day at 7 a.m. and go to work at his studio,"

Aydin says. "He only came home for lunch for 30 minutes

and then went back to work at his studio until evening."

"Whenever I saw him, he was busy with work," Adila

remembered. "I often asked my father why he worked so much.

He would tell me, 'I want to reclaim all that time that I've

lost. Those years took all of my ideas, works and memories away

from me. That's why I have to make the most of the remaining

years of my life.'" Aydin says it was rare for his father

to work with colors after he returned from prison: "He worked

almost exclusively in black and white. Maybe he felt like he

didn't have enough time to master the use of color. Or maybe

being in an environment of stark white snow had affected his

sight, robbing him of his ability to deal with the nuances of

color."

Fellow artist Rasim Babayev (1927- ) encouraged Rezaguliyev to

work with linoleum prints because the technique was less complicated

and didn't require the use of color. Taking Babayev's advice,

Rezaguliyev went on to create numerous prints, including more

than 150 black-and-white prints depicting the Baku of his childhood.

Time and again, until the end of his life, he kept adding works

to what he called his "Old Baku" series.

"All of the ideas and memories from his heart were included

in this series," Aydin says. "Here were the old characters

that he remembered from his childhood: the 'Pomegranate Vendor,'

the 'Oil Seller' and the 'Lamplighter'. He knew them all by heart.

They are among my favorite works of my father's."

Many of Rezaguliyev's prints show people involved with daily

chores, whether it be washing carpets, lighting lamps or selling

water. One wonders if he paid so much attention to the routines

of everyday life because he himself was deprived of the chance

to be involved with such mundane activities during his nearly

25 years of exile.

Due to his hard work, Rezaguliyev managed to gain a reputation

before his death in 1974. In 1963, at age 60, he had his first

solo exhibition. In 1964, he was named Honored Art Worker. His

works were featured in museums throughout the Soviet Union, including

the Pushkin Museum, the Hermitage and the Museum of Eastern People.

Next year marks the 100th anniversary of Alakbar Rezaguliyev's

birth. A Jubilee will celebrate his creative life in the midst

of extreme hardship.

______

This article was based on several

interviews with Aydin Rezaguliyev conducted by Betty Blair, Jala

Garibova and Gulnar Aydamirova, plus the recorded interview with

the late Adila Rezaguliyeva that appeared on the television program

"Yaddash" (Memory) on AzTV.

To read more about Alakbar Rezaguliyev, see the article "Street

Scenes from Yesteryear: The Linoleum Prints of Alakbar Rezaguliyev"

in AI

8.2 (Summer 2000).

To view more than 70 of his prints, visit AZgallery.org.

Originals of his works may be found in various office buildings

throughout Baku, including the Regus offices in the Landmark

Building and the International Bank of Azerbaijan. You may visit

the Baku art studio of his son Aydin, also an artist, and see

prints created by his father by calling

(994-12) 39-44-19.

Back to Index AI 10.3 (Autumn

2002)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

During his exile,

Rezaguliyev underwent an arranged marriage. His father, mother

and future

During his exile,

Rezaguliyev underwent an arranged marriage. His father, mother

and future