|

Autumn 2002 (10.3)

Poetic Justice

Memoirs

of Poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

The rule of society must correspond with the rule

of nature. You can't make people think a certain way if they

don't want to. If they hold certain beliefs, can you really force

them to think differently? - Bakhtiyar Vahabzade The rule of society must correspond with the rule

of nature. You can't make people think a certain way if they

don't want to. If they hold certain beliefs, can you really force

them to think differently? - Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

Even though the Soviet censors were very strict in Azerbaijan,

poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzade (sometimes spelled Vahabzada or Vahabzadeh)

found a clever way to circumvent them. He wrote symbolically

to disguise his hatred for the Soviet system. Vahabzade knew

that his audience would understand the symbolism and read between

the lines.

Even though he was convinced that the collapse of the Soviet

Union was inevitable, Vahabzade, who was born in 1925, says that

he never dreamed that he would live to see the day himself that

Azerbaijan gained its independence. Now, as a Member of Parliament,

he has the opportunity to freely speak out about the issues that

have been troubling him all of his life - in particular, the

demise of the Azeri language.

The day that Azerbaijan declared its independence from the Soviet

Union - November 18, 1991 - was the happiest day of my life.

I cried all day long with joy. This was my greatest dream for

Azerbaijan.

Now that we have our independence, admittedly,

we aren't as happy as we thought we would be. We've come to realize

that even though the Soviet system was extremely repressive,

it had its good points, especially related to medicine and education. Now that we have our independence, admittedly,

we aren't as happy as we thought we would be. We've come to realize

that even though the Soviet system was extremely repressive,

it had its good points, especially related to medicine and education.

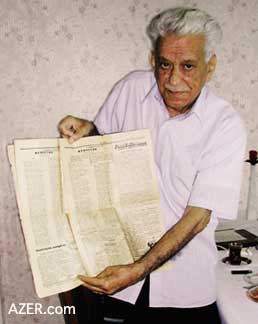

Left: Bakhtiyar Vahabzade, Azeri poet and

Member of Parliament

For instance, up until the Soviet period, an estimated 80 percent

of Azerbaijanis were illiterate. Take my own family as an example:

My grandfather, father, mother and all of my uncles couldn't

read or write, except for one uncle who had studied a few years

at a religious school. My brother Isfandiyar, who's a few years

older than me, was the first person in our family to get an education.

The first thing that the Soviets brought us was education. In

the 1920s, they launched "Eradication of Illiteracy"

[LikBez] courses to teach everyone - men and women. By 1935,

illiteracy had virtually been wiped out. In just 20 years, the

Soviets had begun to educate an entire nation.

Schools of higher education were opened, such as the Academy

of Sciences, the Pedagogical Institute, the Music Conservatory

and the Medical University. A generation later, 90 percent of

the positions were filled by Azerbaijanis. This illustrates tremendous

progress.

Today, education is not free as it was during the Soviet period

and so the situation is not as it used to be. Azerbaijani families

want a decent education for their children, but many of them

can't afford it. I mourn this loss for our country.

Onion

The onion looked at its skin and thought,

And then turned its head to me: "The winter will be severe."

"How do you know?"

I asked.

"From the skin," it

replied. "It's thick,

That means the winter will be harsh."

Nature has been wise from its

very creation,

And is a harmony of rules.

Before creating a mountain,

It chooses a route for it.

To equip the onion for cold winter,

It makes its cloak warm and thick.

Bravo! What mercy!

What generosity,

But, alas! I haven't received it.

Am I not your child, just like the onion, Mother Nature?

I am also cold.

Where was your mercy when you created me?

I'm shivering with cold in the snowstorm of grief and sorrow.

You took care of the onion.

Am I less precious than an onion?

What are these thoughts? What

are these sufferings?

You gave me but one heart, but thousands of torments.

Why do you torture me

More than I can bear?

Pleas for Help Pleas for Help

We are facing so many problems and difficulties now, especially

after losing more than 15 percent of our territory [Nagorno-Karabakh

and neighboring provinces] to Armenia. Unemployment has gone

up, and many Azerbaijanis are emigrating to Europe in search

of jobs.

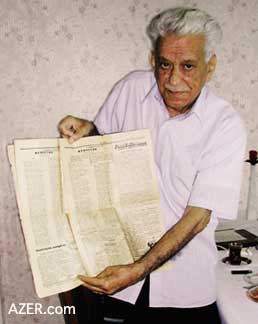

Right: Vahabzade holding up a copy of "Shaki

Worker", the newspaper that published his controversial

"Gulustan" poem in 1959. He lost his job as a professor

after the poem drew the attention of Party officials.

Every day, I receive 10 to 15 letters from people living outside

of Baku who are asking for jobs. They have lost all hope and

are turning to me for help. Azerbaijanis have a great deal of

faith in their poets and aghsaggals. ["Aghsaggal",

literally "white beard," refers to an elder who is

respected for his wisdom and experience.] If people feel injustice,

many of them turn to me.

Sometimes when I read those letters, I can't fall asleep at night.

They burn inside me like a fire. I'm a son of this nation. I'm

a Member of Parliament. I have my salary and can live on that.

But there are so many people out there who have no income. If

you take care of just your family and focus on your own life,

everything may seem to be all right. But if you ponder the fate

of the entire nation, you see that our situation is dire indeed.

Each day, I spend most of the morning on the phone, calling Ministries

or other offices to find a way to help the people who send me

those letters. I have to mention that I'm grateful to the Ministers.

They listen and try to help as much as possible.

Then, twice a week, from 12 to 4 p.m., I attend Parliament sessions.

The most productive time for me to write poetry is in the middle

of the night, from 11 p.m. to 4 a.m. Since I don't have to deal

with any telephone calls at that time, I can concentrate and

work. This is when I can achieve a dialogue with myself.

I just finished writing a new play called "Competition",

which talks about what capitalism has brought us since we gained

our independence. I discuss how it has spoiled our mentality,

especially in terms of our moral values, and how money has started

to dominate our lives. I also touch upon unemployment. Near my

home there is a street corner where unemployed teachers and engineers

go to offer and sell their labor.

Empire of Evil

Don't get me wrong: I have no desire to go back to the Soviet

system. Even while I was growing up in Shaki, I knew firsthand

that the Soviet Union was built on violence. In 1930, there was

an uprising in Shaki against the Soviet government's collectivization

policy. Even though I was only five years old at the time, I

clearly remember the Soviet army's violent crackdown on protesters.

Thousands of people were jailed, and some of them were shot.

President Ronald Reagan called Soviet Union an "Empire of

Evil." That was the expression he always used, and it was

true. Revolution itself means violence. This process went on

right in front of our eyes. Kaganovich, Molotov and then Kalinin

were removed from the government. Even their wives were arrested.

But they couldn't go and visit their wives because they were

afraid. I wrote a poem in 1989 describing the situation:

Kaganovich served the Leader

[meaning Stalin] with loyalty

Said "yes" a hundred times to each of his words.

They arrested his wife,

Then they arrested Molotov's wife,

After that-Kalinin's wife.

The husbands kept silent.

They had to swallow their anguish.

At this moment I recollected

the history of Russia.

Decembrists* stood in front of my eyes.

They were arrested as well,

And convicted unfairly.

Their wives followed them one by one.

I compared that period to this

one

And couldn't figure out:

Who was man, and who was woman?

* A Decembrist was a participant in the unsuccessful conspiracy

to overthrow Czar Nicholas I of Russia in December 1825.

I knew that the Soviet Union

would eventually collapse; it was an illogical, corrupt system.

All poets and writers have this kind of intuition; it's a strong

feeling that enables us to sense the future.

The rule of society must correspond with the rule of nature.

You can't make people think a certain way if they don't want

to. If they hold certain beliefs, can you really force them to

think differently?

During the Soviet period, everyone had a job and everyone had

enough to eat, but we were always living in fear - always.

During Khrushchev's "thaw" (1959-1964), the atmosphere

became milder, but during the Brezhnev period (1964-1982), the

situation again became more severe; in the Andropov period (1982-1984),

it got even worse.

We constantly lived in fear of the KGB. For one thing, we had

no freedom of religion. We couldn't worship God as Muslims. At

best, we were only permitted to have one mosque open in Baku

- the Taza Pir mosque. The others barely functioned. True, the

Blue Mosque was functioning, but only old people went there.

Our native language was suppressed, and gradually we started

to forget Azeri in favor of the official language-Russian. I

couldn't accept this idea. Azerbaijani parents pushed their children

to study at prestigious Russian schools, which naturally only

led to the demise of Azeri schools. The children who studied

in Russian schools could barely speak Azeri.

Subjugation-Freedom

Our nation was burned in the fires of slavery,

We were wounded and scorched for the sake of freedom.

But having reached freedom in this temple,

We made our thanksgiving prayer without the Qibilah.*

Now we are free, but free from

the honor we had

That once protected us from evil.

Now that we are free from the fury and anger of the enemy,

Our nation has become the target of its own hatred.

Having freed ourselves from others' subjugation,

We have succumbed to our own slavery.

We are free from benevolence

and mercy,

We must reject the nation's right.

We became the brutal plunderers

Of our own Motherland.

No other nation can replace

us in deception,

This one blames that one, and that one accuses this one.

While we plunder and pillage our Motherland,

We are free from the fear of Allah.

My freedom is my enemy;

Fate itself cannot make heads or tails of this secret game.

The rope that pulled me out of the deep, dry well

Is now wrapped around my neck like a noose.

* Muslims face Mecca when they

pray.

Translated by Aynur Hajiyeva

Secret Symbols

I turned to poetry to protest against the Soviet regime, using

symbols to disguise the true meaning of my writing. For example,

I would reference another period in history or a different country

in order to address the issues that I wanted to write about.

But the astute reader understood that the problems I brought

up actually described Azerbaijan.

For instance, my poem "Latin" (1967) describes the

situation that I came across in Casablanca. Arabs living in Casablanca

could not speak their mother tongue. In the poem, I compared

Latin with the Arabic of the Arabs living in Casablanca. Even

though the Roman Empire no longer existed, the Latin language

was still alive, but for the Arabs living in Casablanca, though

their nation was alive, their language was essentially dead because

they were not using it. In my poem, I described the situation

in Casablanca, but my audience knew to read between the lines

and think about the declining state of the Azeri language right

here in Azerbaijan. I wrote:

If you cannot say, "I am

free, I am independent"

In your mother tongue,

Who can believe that you really are independent?

The KGB got suspicious of me,

but they couldn't prove that the poem was actually about the

Azeri language. But after that, it became much more difficult

for me to publish my poems and get them past the censors.

All of my speeches and actions were under close observation.

The KGB tapped my phone conversations. They kept track of where

I went and who I met and spoke with. I knew someone who worked

for the KGB; he was from Shaki, just like me. He warned me to

be careful during my university lectures. He even told me which

of my students were KGB spies. Every class had them. That was

the most dangerous period of my life.

Eventually, one poem that I wrote cost me my job. I worked as

a professor at Azerbaijan State University from 1951 until 1990.

I lost my job for writing the poem "Gulustan" (1959).

This title referred to the 1813 Gulustan Treaty that divided

Azerbaijan into two parts: Northern Azerbaijan (the modern-day

Republic of Azerbaijan) and Southern Azerbaijan (part of Iran).

I knew I couldn't publish the poem in Baku - it was too controversial.

At that time, there was a newspaper in my hometown called "Shaki

Worker" (Nukha Fahlasi), so I published it there. Even though

the newspaper didn't have a very broad readership, my poem caught

the Party's attention three years later.

In 1962, the Central Committee discussed my poem at a Party meeting.

The members decided that I should not remain at the university.

Their pretext for firing me was that I was "propagating

nationalism". At the time, it was very dangerous to be labeled

as a Nationalist or Pan-Turkist.

I insisted that they show proof of this charge, so they produced

a female student as a witness. Her testimony "proved"

that I was an anti-Russian propagator. Two days later, the girl

came to my place in tears and told me the story. Apparently,

she had failed her political economy exam. They had promised

her that if she became a witness against me, they would give

her an excellent grade on the exam. Otherwise, she wouldn't receive

her student stipend, which was the income she depended upon to

live. That's how they forced her to make accusations against

me. I told her that I didn't hold her responsible for what had

happened.

After I was dismissed from the university, I was in a desperate

situation. I couldn't find a job. I couldn't publish my poems.

I wasn't allowed to work in radio or television. We were starving,

so we had to sell my wife's jewelry just to buy food. My children

- Gulzar, Isfandiyar and Azer - were very young at the time.

Back then, the KGB used to arrest people in the middle of the

night, usually after 1 a.m. Those infamous black cars would come

and whisk people away, never to be seen again. Everybody knew

about those dreaded cars. I feared that they were going to come

and arrest me, so I used to wait up until past 2 a.m. to go to

bed. That was the period between 1962 to 1964 - three years.

[For more about the mysterious government cars that would take

people away in the middle of the night, see Anar's short story

"The

Morning of That Night" in AI

7.1 (Spring 1999). Search at AZER.com.]

My friends knew about our family's desperate situation, but many

of them couldn't help us for fear that they would be targeted,

too. One person used to send us a basket of food every Sunday.

At the bottom of the basket, some money would be tucked away

in an envelope. I suspected that the actor Hasanagha Salayev

was the one leaving us the basket, but when I asked him about

it, he swore that it wasn't him.

Each week, a child would come to our place, ring the doorbell,

place the basket beside the door and run away. By the time I

managed to get to the door, I could see no one, but I could hear

footsteps. Once I watched and caught the lad when he was bringing

the basket to us. I asked him to tell me who had sent it. He

started crying and said that he had promised never to reveal

the name. This went on for two years: the basket was left on

the doorstep every Sunday. After Hasanagha's death, I found out

that he really was the one who had helped us. He couldn't tell

me simply because he was afraid of being found out.

I was so fearful for my safety that I decided to go live in the

town of Shaki in the northwestern part of the county at the foothills

of the Caucasus. Shaki was my birthplace. The KGB granted permission

for me to move there, probably because they didn't want me to

be in contact with other people. My wife stayed behind in Baku

with our children.

That was a very stressful period for me. I became so nervous.

I used to stay at home all day and not go out. I didn't want

to see anyone. My relatives in Shaki helped me out a lot, but

they were afraid, too. They would wait until 11 or 12 in the

evening to pass me money.

Finally, in 1964, Heydar Aliyev called me and told me that he

wanted to help me out. He was working for the KGB at that time

as a deputy. It was Aliyev who helped me return to my job at

the university.

I eventually found out that Aliyev had protected me the whole

time. A friend at the KGB told me that someone in a very high

position was protecting me, but he didn't tell me who it was.

Years later, I learned that it was Aliyev. Apparently, some of

the Communist officials had wanted to have me arrested, even

though I had committed no crime. Aliyev stood up for me and insisted

that I loved my country. In essence, he was the one who saved

my life. He didn't tell me anything about this. I think he didn't

want to make me feel like I owed him something.

I Must Be Myself

Perceive and understand yourself,

Stop bowing first to this one, then to that one.

By flattering others so much

You're your own worst enemy.

We lost ourselves completely,

Where's the vigor, where's the pride?

The old East that once ruled the world

Is now acting upon the orders of the West.

By God, we got sick and tired

of bowing to strangers,

But we didn't get bored of imitating others.

We lost ourselves, we become unrecognizable

Because of mixing our pure blood with others.

This world doesn't want to recognize us,

We let ourselves get drowned in imitations.

I want to be known by my own

voice,

Enough that I lived like a convict,

I want the eyes of the world to see me

The way I am: with my good and my evil.

I am the way I am, whether black or white,

Why should I imitate others?

I have to be myself, only myself,

If I am not myself, then I am nothing.

July 1996

Translated by Aynur Hajiyeva

Language Reform

In 1982 I was elected a Corresponding Member of Azerbaijan's

Academy of Sciences, and in 1984, I was awarded the highest title

of "People's Writer of Azerbaijan." That same year,

I received the USSR State Award for my book, "We Are All

Passengers on One Ship." When I gave my acceptance speech

in Moscow, I decided to do it in Azeri. I knew Russian, but I

deliberately gave my speech in Azeri, forcing the organizers

to translate my speech. They did, but as you can imagine, they

weren't happy about it.

I've been a member of Parliament now for more than 20 years.

I think that when I was selected, they were hoping that I wouldn't

stand up for the truth and that I would overlook the injustices

of the system. But I proved them wrong.

These days, because of my age, I don't address Parliament as

much as I used to. However, I recently did make a very strong

statement about language usage, insisting that everything should

be in Azeri, our native language.

Here in Azerbaijan, the Russian language - not our native Azeri

- has been the prestigious language for decades. I remember once

after Independence when seeing my son off at the Baku Airport,

I heard the boarding call for Azal [Azerbaijan Airlines] being

announced in Russian. Soon afterwards, I met with Jahangir Asgarov,

the head of the airline, and strongly recommended that Azeri

be used.

At the time when I made my speech in Parliament advocating the

strong usage of Azeri, some of the Ministries were still using

Russian. Can you imagine! Even some of the ambassadors said that

they received letters in Russian. I am pleased to see that recently

there has been a great deal of progress toward strengthening

Azeri.

In my speech, I also stated that all Azerbaijani children should

be required to finish secondary school in Azeri. It's important

for our children to learn Azeri while they're still young; if

not, they'll never learn it at a professional level. Students

in the Russian track know about Russian czars like Peter the

Great, but they've never heard of Azerbaijani shahs like Shah

Ismayil Khatai. If they know writers like Pushkin and Lermontov,

they should also know about their own literature and writers

such as Nizami, Fuzuli, Mirza Jalil, Sabir and Samad Vurghun.

I'm not saying that Azerbaijanis shouldn't learn Russian. Of

course, they should know Russian. World literature comes to us

through Russian because so little of it has been translated into

Azeri. My grandchildren study in the Azeri track but they also

know Russian and English. I had my grandson read "An American

Tragedy" by Theodore Dreiser. If he had not known Russian,

he would not have been able to read it.

I want all of our children to go to Azeri schools, but at the

same time, not be limited to knowing just their native language.

The educational system should help them become fluent in Azeri,

English and Russian.

Complaining of

Age

When I was 15 and 20,

I was thinking 40 is an old age.

I am reaching 50 now.

Still I have my childhood wishes

Whirling in my brain.

As if it were yesterday

When I was going to school

Munching on sunflower seeds

And carrying my rucksack on my back.

As if it were yesterday

When I was riding my horse made of reeds.

I cannot feel my age-what can

I do?

The heart is the same heart,

The wishes are the same wishes.

My heart flies now to highlands, now to lowlands-

What are these feelings in my heart?

I feel sometimes as if I am

yesterday's kid,

I laugh at these strivings...

But I don't blame myself,

Time was so short,

Time has been flying...

As soon as we lose our youth

We grasp life with four hands.

Like trees, our roots go deeper

As we grow older.

Look! There is a rumpus in the courtyard.

The kids are running and climbing the fence.

I would give anything now to be able to play

Hand in hand with them

And escape into my childhood...

I want to play hide-and-seek,

Along these meadows, across these fields.

I want to hide so that

Old age cannot find me ever...

But age manifests itself sometimes,

There are so many hidden beats in the heart,

When I am short of breath in the street,

I blame the stones or the ascents on my way.

When I lag behind my children,

I cannot blame the stones or the ascents, I know

But when I admire beauty,

I feel the same age as my son.

Translated by Jala Garibova

Alone

I always feel alone even among people,

My days have become longer and nights come later,

When I am alone with my thoughts

Each of my thoughts becomes a friend to me.

Even the leaves of that lone tree would turn yellow,

If it didn't have support.

I wish for the lion not to be alone,

While it is the king, sultan of forests.

If there were no fire, water could not boil in a pot.

A bird cannot fly over a mountain with a single wing.

Translated by Aynura Huseinova

Bakhtiyar Vahabzade was interviewed by AI Editor Betty Blair

and Jala Garibova. See "Profile

of a Dissident: Bakhtiyar Vahabzade" in AI

7.1 (Spring 1999).

____

Back to Index

AI 10.3 (Autumn 2002)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

Pleas for Help

Pleas for Help