|

Winter 2002 (10.4)

Pages

68-69

Alphabet Changes

The Upside

- Down "e" - an Editor's Nightmare

by Betty

Blair

When we first started publishing Azerbaijan

International in January 1993, we soon ran into problems printing

the new Azeri Latin alphabet that had just been adopted in December

1991. The major culprit was that peculiar character that we dubbed

"the upside-down 'e'" (the schwa) which does not exist

on standard Latin-based computer keyboards. In fact, no language

uses such a letter. Consequently, back in those early days, we

soon discovered that if we wanted to publish anything in Azeri,

we had to design our own fonts. When we first started publishing Azerbaijan

International in January 1993, we soon ran into problems printing

the new Azeri Latin alphabet that had just been adopted in December

1991. The major culprit was that peculiar character that we dubbed

"the upside-down 'e'" (the schwa) which does not exist

on standard Latin-based computer keyboards. In fact, no language

uses such a letter. Consequently, back in those early days, we

soon discovered that if we wanted to publish anything in Azeri,

we had to design our own fonts.

Theoretically, the problem has now been solved via fonts created

for UNICODE which enables IBM and Mac computers finally to "talk"

to each other using the upside-down "e". Yet, in essence,

the problems related to file sharing, viewing Web sites, writing

e-mails and doing spell checks won't be resolved until every

computer user has an advanced enough system to accommodate the

necessary fonts. Eleven years have passed and the nightmare has

not really disappeared. Little did we know back in 1993 when

we wrote this article what kind of monster the schwa would turn

out to be.

Actually, I wasn't aware that

any problem existed with the Azeri alphabet until I walked into

one of Baku's highest educational institutions this past June.

One of the top administrators confided, "We really have

a problem with our new alphabet - it's that upside-down 'e' (the

schwa). Do us a favor: in your next issue of Azerbaijan International,

replace it with a combination "ae" or some such letter,

and put a footnote at the bottom of the page explaining what

you've done. The Latin alphabet is capable of handling every

sound in our language. We shouldn't have created a letter that

was outside the standard Latin alphabet."

I listened. This wasn't just some academic who happened to be

disgruntled about a pedantic, esoteric matter. A respected linguist,

he had been a member of the government's advisory board that

had helped make the decision to adopt the new Latin alphabet

when Azerbaijan gained its independence in 1991 and to rid themselves

of Cyrillic which had been imposed on them by Stalin's regime.

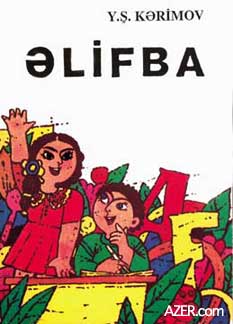

Photos:

(below left) Azerbaijan's

first alphabet primer in the new Azeri Latin script was introduced

in the 1992 school year and prepared by Yahya Karimov. Its bright

and colorful illustrations are delightful, playful and culturally

relevant to Azerbaijan, unlike the primers of the Soviet era.

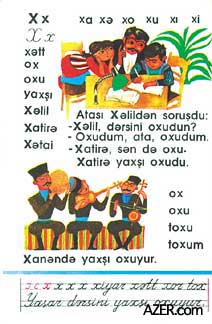

(below right) One of the many attractive and culturally

relevant pages of Y.S. Karimov's "Alifba", the first

alphabet primer published for first graders in the Azeri Latin

script, 1992. Note the nationalistic trends evident in the illustrations,

such as the mugham trio pictured here with khananda singer with

gaval, and the tar and kamancha players.

"We were mostly linguists on that committee who made the

decision to adopt the new Latin alphabet," he said. "We

knew all about language, but we didn't have the technological

computer expertise to anticipate all the complications we were

getting into when we created a few letters of our own."

That troublesome upside-down "e" represents the /æ/

sound in the Azeri language. (In English, it's like the vowel

sound in the words "fat cat.") The difficulty is that

Azeri is the only language in the world that uses this letter.

Curiously enough, this symbol was not included in the original

alphabet that was adopted on December 25, 1991. At that time,

the schwa sound was represented by an "a" with two

dots (umlaut-ä). But since this sound is the most frequent

in the entire language, the dotted "a" became very

cumbersome. Not only was it awkward to write all those dots;

it was slow and tedious and didn't appeal aesthetically, no matter

whether the letter was written by hand or typed.

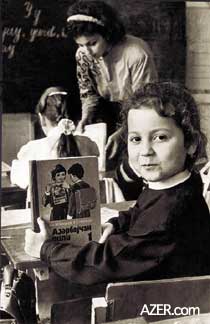

Left: First grader at a Russian-language

school shows off her Azeri-language primer written in the Cyrillic

script. In the early 1990s when this photo was taken, Azeri Cyrillic

was still much more widely used than the modified Latin script

which was officially adopted in December 1991 (Photo: Litvin). Left: First grader at a Russian-language

school shows off her Azeri-language primer written in the Cyrillic

script. In the early 1990s when this photo was taken, Azeri Cyrillic

was still much more widely used than the modified Latin script

which was officially adopted in December 1991 (Photo: Litvin).

For example, the first

name of Azerbaijan's first elected President is Äbülfäz,

which, when written with the new alphabet, needs six dots. Arabic,

a script notorious for its dots, uses only three; Cyrillic, none.

And so it was that on May 16, 1992, the first official change

was introduced into the six-month-old Azeri Latin alphabet; the

upside-down "e" was resurrected, like the eternal phoenix

rising from consuming flames. There was a history to its reappearance.

Actually, it was one of the oldest letters in the non-Arabic

representation of the Azeri language. Created in 1928, when the

Latin script was originally adopted, this letter somehow managed

to escape unscathed during the Cyrillization (1939-1991) of the

Soviet era. For that reason, it's shape, though strange to Westerners,

was very familiar to Azerbaijani readers.

(But back to my story.) Time passed. I returned to California

and had a chance to speak with some of the professors teaching

Azeri classes in universities in the United States.

"What are you doing about the upside-down 'e' in the new

script?" I asked.

One paused, "Well, I don't have it on my computer yet, so

I'm writing out all the instructional material by hand."

Another was managing quite fine, except for "the e"

(as we soon came to call it). "I could work ten times faster

if I could find a typeface with 'the e,'" he told me. At

first he had tried using the symbol known as "partial differential"

() on the standard keyboard. But it really didn't align well.

Like a tall, awkward, gangly kid who is always standing head

and shoulders above his peers, somehow this shape just didn't

fit. Then he managed to find a Cyrillic Azeri typeface, and so

every time he needed "the e", he had to copy and paste

it in-sometimes two or three times in a single word. The last

time I talked with him, he had finally managed to get a customized

typeface - and life was just fine.

I called a U.S. company that has a joint-venture project in Azerbaijan.

"The upside-down 'e'? Well, we don't quite know what to

do," they told me. "I'm sure someone can design it

for us if we need it - but we're still in a dilemma about which

language to use - Russian or Azeri. We're trying so hard to be

appropriate and sensitive. It's really important to us not to

offend anybody."

Shortly afterward, I contacted a good friend of mine who is a

computer programmer. I wanted to explore the implications of

designing a new letter for the computer. "It's no problem,"

he said. "No big deal. You can design any shape you want.

There are plenty of software packages available to design your

own font."

He failed to mention that the cost for these "design-it-yourself"

software packages begins at about $250, and in my own case, where

would I find the hours to sit and plod through some manual to

figure how to make an upside-down "e"?

I asked my friend to do a little research to find out what other

implications there might be for the computer, such as international

copyright regulations and e-mail transmission.

Copyright turned out to be, as he put it, "a can of worms."

Legally, you can't just add a letter or two to an existing font

that somebody else has created and then sell it as your own.

As for e-mail, transmission is possible, though a bit involved,

as "binary file transfer" (which preserves the text

exactly as written) must be used (software packages like UUENCODE

and UUDECODE). Of course, both transmitter and receiver need

identical Azeri fonts.

But my friend soon tired of the subject, and it wasn't long before

he was sending me an e-mail, saying, "Come on, Blair, quit

'e-bashing' (obviously new slang for what he perceived me to

be doing to the Azeri alphabet). Lay off. I told you everything

is possible with computer technology. Don't go making such a

big deal over this 'e.'"

"Hey look, I'm not 'e-bashing,'" I tried to defend

myself. "Sure, computers can do everything if you have the

social and economic infrastructure to support it. But at what

price? No one can afford to buy fonts for $100 in Azerbaijan.

Doctors only make $20-$30 a month (U.S. currency equivalent).

It would take half a year just to earn that amount of money.

And with rampant inflation and the war - it's totally out of

the question. "And," I continued, "if the 'e'

weren't such a big problem, how is it possible that you can walk

into any bookstore in Baku and count on one hand (no exaggeration)

the books that have been published in the new Latin alphabet?

Nearly two years have passed since the alphabet was officially

adopted, and Azerbaijanis are a highly literate society. But

where are the books in the new Latin alphabet? There's a real

problem here.

"If you take a very close look at the Ministry of Education's

first primer (Karimov, 1992), it seems they had to customize

every single upside-down 'e' by first printing an 'o,' then drawing

a line through the center and cutting out a little wedge-an incredibly

painstaking process."

Somehow, my friend still wasn't convinced of the complications

involved, and it wasn't long afterwards that his friends started

calling me.

"Why are you making such a big deal about the upside-down

'e'?" they wanted to know.

"Look, Azerbaijan simply can't support it. Economically,

they're a new nation struggling to enter the market economy,

and they should tap into the huge investment (time, money and

intellectual talent) that is awaiting them by using the standard

Latin computer keyboard. They're a small country-only 7-8 million

people. Who's going to manufacture a typewriter for such a small

market? And thousands of typefaces already exist for the computer.

Why should they redo the work that's already been done for them?"

Days passed. More complications with the Azeri script became

evident as we continued to try to put the magazine together.

Our typeface, which obviously had been designed for 12-point

size print, couldn't produce the "hatted g" when sized

larger or smaller. And we had not gotten around to producing

a bold or italic set.

E-mail transmission was out of the question, since none of us

had the required software. In fact, we couldn't even swap disks

with anyone else who had Azeri Latin fonts. Since everybody had

tried to solve the problem on his own, the upside-down "e"

on each customized typeface had been assigned to a different

key. On one, you pressed "option + zero"; on another,

"alternate + comma", and a third required three strokes

"alternate + shift + z."

The ergonomics were dizzying. Ideally, the most frequently used

sounds in an alphabet should be represented by keys that are

on, or, at least close to, what is known as the "home keys"

(a-s-d-f or j-k-l-;) so that the typist can type quickly. But

our font had positioned the upside-down "e" with option

plus the zero key. To type it was like making the little fingers

of each hand pirouette like ballerinas across a stage in opposite

directions.

Moving off the home keys so frequently to the extreme edges of

the keyboard makes it difficult to return to the home keys successfully

and could result in a whole string of misspelled words. Let's

not talk about what happens to one's speed with these customized

letters - when two, three, and sometimes four strokes are required

to produce one character.

Then there was the problem of font style. Among the customized

Azeri fonts that exist in the United States right now, most of

them resemble Times - a font with serifs. Azerbaijan International

magazine uses Helvetica which is not based on serifs. So our

English font doesn't match the Azeri.

When we needed a single letter from the Azeri alphabet (as an

example for this article in English), we had to open up the Azeri

font and "paste" it in every single time. Despite all

that effort, it had to be re-aligned each time, as it was slightly

lower than the other letters. It was also thinner. And it didn't

match font styles. But the telephone calls from "friends"

weren't over. "It looks like you're really saying that the

Azerbaijanis should simply adopt the English alphabet",

one of them kept pounding away at me.

"Not at all," I replied. "I wouldn't wish the

English alphabet on anybody - especially with its incredible

lack of sound-symbol correlation. We have too few symbols to

represent so many sounds, especially the vowels. No, let Azerbaijanis

designate all their vowels. Just let them find a creative way

to do it on the standard keyboard. There are all kinds of diacritical

marks that can be added (¨ ´ ` ) not to mention the

"æ" that already exists as one letter.

"It's obvious that the Azeri alphabet designers were really

thinking with pen and pencil when they added these new characters.

There's no problem to add a little tail or slash to an 's' or

a 'c', or to omit a dot from an 'i' when it's done by hand -

it's only a slight variation. But when it comes to computers,

either the letter exists or it doesn't.

"That's why the new Azeri Latin alphabet, seemingly so close

to the one used in the Western world today, is, in reality, so

far away."

"But, then, you're making the alphabet dictated by technology,"

my friend countered, unwilling to give up. "Azerbaijanis

should be able to choose any symbol they want. Technology should

serve them."

"You're right. Man should not be a slave to technology.

The 'tail shouldn't wag the dog'. But that's idealistic and unreal.

Technology always has its own limitations and parameters. It's

not the first time technology has shaped the alphabet. The same

story has been repeating itself since the origin of the alphabet.

Greek and Latin were clearly determined by the hammer and chisel

against marble - it's easier to carve straight lines in stone

than rounded ones. That's why so many of our capitals are based

on straight lines. The cursive Arabic was influenced by pen;

cuneiform, by clay and sharp stick. Other alphabets were created

by carving on bamboo. Simply today, the determining tools are

fonts, computer keyboards, and satellite transmissions - the

only difference being that they're a bit new and unfamiliar in

the alphabet designers' hands."

In the end, alphabets are really all about communication, not

isolation. They're simply codes to represent speech and provide

a means to express ideas beyond time and space. Azerbaijanis

don't need to 're-invent the wheel'. A whole vast world is out

there ready to propel them into the 21st century if they can

only find creative ways to fit their own unique language and

circumstances into it.

Paul Jordan-Smith of UCLA's

Office of Academic Computing contributed to this article.

____

Back to Index

AI 10.4 (Winter 2002)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|