|

Winter 2002 (10.4)

Pages

58-63

Black January - Baku 1990

Behind

the Scenes - A Photojournalist's Perspective

by Reza with

Betty Blair

Left: Soviet tanks in Baku during the week

of January 20, 1990. Reza secretly took this photo through a

car windshield because it was too dangerous to openly photograph

the Black January events. Photo: Reza. Left: Soviet tanks in Baku during the week

of January 20, 1990. Reza secretly took this photo through a

car windshield because it was too dangerous to openly photograph

the Black January events. Photo: Reza.

To add to the record [January

15, 2008]: This note from Ramiz Abutalibov, who represented Azerbaijan

at UNESCO during the Soviet period.

"Concerning the trip that

Reza made to investigate the Black January 1990 events. There

were three journalists from Paris: Reza, Ahmed Sel and Ms. Shirin

Malikova. I got them visas in Soviet Consular in Paris to Moscow,

which was very difficult to do at that time. Then Rustam Ibrahimbeyov

[famous filmmaker] organized their trip to Baku by train. My

daughter Nigar Abutalibova met them in Baku and helped with arrangements

for a car and their program in Baku. All these preparations behind

the scenes were a mutual effort and involved several of us."

Azerbaijanis call it "Black January", meaning the massacre

of civilians that occurred on January 19 and 20, 1990, when Soviet

tanks and troops took to the streets of Baku. Operation "Strike"

(Udar) was intended to crush the makings of an independence movement

in Azerbaijan. Officially, 137 people were killed; unofficially,

the figures swell to at least 300 and possibly more. Even to

this day, more than eight years later, the real truth is unknown,

as apparently most of the documents - 200 boxes, according to

some accounts - were confiscated and sent back to Moscow by the

Soviet Army when it became clear that the Soviet Union was on

the verge of collapse.

Black January turned out to be the beginning of the end of Soviet

rule in Azerbaijan. Communist Party members, who had devoted

their lives to serving the interests of the USSR, were appalled

to find the system turning against them. Stories abound of Party

members setting fire to their membership IDs. Azerbaijan's current

President, Heydar Aliyev, a former member of the Politburo, waged

a scathing attack on Gorbachev, accusing him of masterminding

this heinous crime.

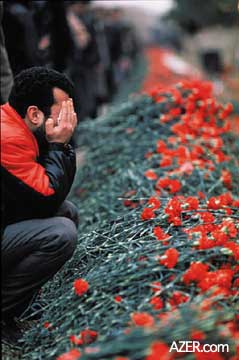

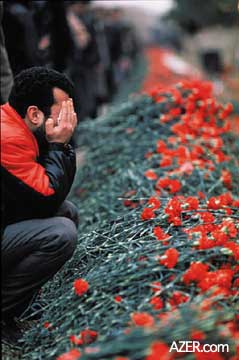

Left: Hundreds of civilians in Baku were

killed by Soviet troops during the Black January massacre. Carnations,

like the ones shown here at Shahidlar Khiyabani (Martyr's Lane)

became the symbol of mourning. Photo: Reza. Left: Hundreds of civilians in Baku were

killed by Soviet troops during the Black January massacre. Carnations,

like the ones shown here at Shahidlar Khiyabani (Martyr's Lane)

became the symbol of mourning. Photo: Reza.

But throughout the confusion

and turmoil, the Soviets managed to suppress nearly all efforts

to disseminate the news to the international community. There

were two notable exceptions: Mirza Khazar and his small team

at Radio Liberty (U.S.-sponsored), who broadcasted daily reports

from Baku, and the efforts of a world-renowned photojournalist

who, for the sake of simplicity, goes by the name Reza.

The following article describes Reza's efforts to smuggle himself

into Baku during those turbulent days and get the story out to

the world. His story reads like a novel or a Hollywood screenplay.

But the scenario is real. Reza lived through all of the tense,

historic moments described below.

Moscow - January 22, 1990. I'll

never forget those days. More than 50 international journalists

and photographers, including those representing some of the best-known

names in the business - CNN, ABC, CBS, NBC, Reuters, AP - had

checked into the Moscow Hotel. I was among them. Two other colleagues

and I had just arrived from Paris. Something was happening in

Baku.

We didn't quite know what. We had heard that demonstrations were

taking place in the streets and that Soviet troops had moved

in. Beyond that, we could only speculate.

It seems the Soviets feared an independence movement was afoot

in Azerbaijan. They sought to crush it before it gained momentum.

Don't forget - those were the days of Gorbachev and Perestroika.

Only a few months earlier, the world had watched the domino effect

taking place, as Central Europe gained its freedom - the Berlin

Wall, then Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Don't forget that

the Soviets, with the world's largest military complex, had also

been forced to withdraw in the face of the unrelenting Afghan

guerrillas.

Left: Demonstrators wave a homemade flag

to signify their desire for independence from the Soviet Union.

Protests like this one provoked a severe crackdown by Soviet

troops in January 2000. Photo: Reza. Left: Demonstrators wave a homemade flag

to signify their desire for independence from the Soviet Union.

Protests like this one provoked a severe crackdown by Soviet

troops in January 2000. Photo: Reza.

I had been catching

snatches of news on the wire services in Paris. Being a photographer,

part of my work is to anticipate clashes and upheavals before

they occur. What good is it to arrive when the action is over?

That's what photography is all about. A journalist can follow

on the scene later on and draw upon many analytical sources,

but a photographer has to capture the spontaneity of the moment.

When I began detecting some disturbances in Baku over the news

wires, I called up my friend Ahmad Sel, a Turkish cameraman working

for a French TV company.

"Want to go to Baku?" I asked.

"Are you crazy?" he replied.

But Ahmad finally agreed to undertake shooting the video. I would

handle the stills. We thought it would be invaluable to take

an Azerbaijani along with us, so we invited Mrs. Shirin Malakova

to join us. In those days, you had to fly to Moscow to get to

Baku - there was no other way. The authorities also required

that you get advance permission for any city you wished to visit.

We knew they would never give us approval for Baku so we didn't

bother to ask.

Despite the run-around that we got from the Soviet Embassy in

Paris, we managed to get our visas in hand by January 20th. That

was the day all hell broke lose in Azerbaijan, though we didn't

know it at the time. It seems the Soviet officials didn't make

any connection either, since we had applied for the visas two

days earlier. They knew I was a photojournalist. I told them

I was going to take photos of Moscow. It was the first of many

lies I would have to tell in order to uncover the truth about

the tragedy of Black January.

Inside Connections

Left: Family members pore through photos

of the dead, looking for lost loved ones. Photo: Reza. Left: Family members pore through photos

of the dead, looking for lost loved ones. Photo: Reza.

In 1988, I had visited

Baku on the occasion of the 150th Jubilee of the great playwright,

Mirza Fatali Akhundov. It was there that I met many prominent

artists and writers, one of whom was Rustam Ibrahimbeyov. A prominent

writer, Rustam would go on to write the screenplay for "Burnt

by the Sun," winner of the 1995 Oscar for Best Foreign Film.

[See AI 3.2, Summer 1995]. Rustam would turn out to be a pivotal

person in our quest to smuggle ourselves into Baku.

I had called Rustam in Moscow several days earlier when I wasn't

able to reach Baku. He had confirmed my suspicions that the situation

was serious. "It could turn into a very bad situation,"

he had told me in very cautious, cryptic Azeri. I had to call

him back twice. Another number, another time. Being a journalist,

you pick up on things like this very quickly.

Now, with visas for Moscow in hand, I called Rustam again. "I'm

coming with two friends. I'd love to see you and have dinner

together."

"Yes," he replied, "it's the right time to come

because 'our friends' are already in!" (He meant that the

Soviet troops had already moved into Baku.)

Our Paris team arrived in Moscow on January 21st. Rustam was

perplexed. He saw no solution for getting to Baku. Now that the

troops and tanks were in the city, all of the roads would be

blocked, and it would be very dangerous to travel.

Back at the hotel that evening, word spread that Moscow's press

officials had organized to fly all of the journalists to Baku

the next day. We were told to meet in the hotel lobby at 9 o'clock

the next morning (January 23).

"Are you sure they plan to take us to Baku?" I asked

some of the other journalists. They were sure. And I was equally

sure they wouldn't. If there was one thing I had learned after

spending more than five years (1983-1988) on assignment with

Time Magazine covering Afghan guerrilla fighters in the mountains

of Pakistan and Afghanistan, it was this: "Never trust Soviet

officials when they make irresistible offers."

Local Train to

Baku

Left: Shrouded corpses from the Black January

massacre, waiting to be identified. Photo: Reza. Left: Shrouded corpses from the Black January

massacre, waiting to be identified. Photo: Reza.

The next morning, Ahmad,

Shirin and I were as far away from the hotel lobby as we could

get. Instead of accompanying our foreign colleagues on the three-hour

flight to Baku, we decided to take a local train. The trip would

grind on for 48 hours, stopping at every little town and village;

however, unlike the express train, there would be fewer security

checks.

Back at the hotel, while we were gone, Rustam arranged for someone

to mess up our rooms every day and make them look "lived

in." We had to keep up the pretense that we had not checked

out in order not to arouse suspicion. Remember, our visas were

only for Moscow.

Rustam's friend Kamal accompanied us on the train. Our first

task was to learn a few Russian phrases: "Ya pa rusky niz

nayu" (I don't speak Russian) and "Ya Azerbaijani"

(I'm Azerbaijani). I was concerned that I didn't know Russian.

Kamal assured me that many Azerbaijanis in the countryside didn't

know Russian either, so I could get by. But if anyone ever stopped

us for our papers, we knew that would be the end.

We did our best to dress like the locals - to blend in, to appear

so ordinary that we would be overlooked and ignored. Shirin spoke

fluent Russian and Azeri as well as French. Ahmad's Turkish accent

was quite obvious, but Russians didn't know the difference.

It was a long ride. Fortunately, we had our own compartment.

Whenever a controller came along, Kamal would warn us and we

would quickly crawl up into the luggage compartment and hide.

Sometimes, when we were sleeping, he would bribe the officer

and request that we not be bothered.

One of our biggest problems involved the toilets, which were

located in the main section of the train. We didn't want to get

ourselves in a situation where we had to speak to anyone, so

Kamal would wait outside our compartment and signal when it was

clear to head down the corridor.

Baku - At Last!

Left: Many Azerbaijanis hung black flags

and strips of cloth from windows, trees and car antennas as a

protest of the Soviet crackdown on Baku on January 20, 1990.

Photo: Reza. Left: Many Azerbaijanis hung black flags

and strips of cloth from windows, trees and car antennas as a

protest of the Soviet crackdown on Baku on January 20, 1990.

Photo: Reza.

We arrived in Baku on

January 24th, tired but full of anticipation. As we pulled into

the station, I looked out the window anxiously. There, standing

and waiting for everybody to get off the train, was a long row

of soldiers! I'll never forget the scene. It was right out of

a spy movie about the Cold War - the only difference being that

this was real life and I happened to be right in the middle of

it.

Tall, husky Russian soldiers stood there with their big, bulky

overcoats and fur hats, cradling their machine guns, silhouetted

against the darkness of the chilly night. They looked so huge

- so foreboding, so threatening. I remember looking at Ahmad

and Shirin with horror in my eyes, saying, "I think they're

going to catch us. We'll have to pass through that wall!"

It wasn't that I was scared of being arrested. That comes with

the territory when you're a photojournalist. You know it can

happen - getting arrested, or beat up. What I feared most was

not being able to get the story. Especially since I am Azerbaijani

myself, I wanted to be part of telling the world this story.

The train came to a halt. We were hoping that Rustam had succeeded

in arranging for someone to meet us. Suddenly, in the crowd I

spotted Elinora Huseinova (now Ambassador to France) with a couple

of her girlfriends. She jumped up on the train, her arms full

of flowers-roses-not the red carnations that were being used

for mourning those days. She gave me a big hug and whispered

in my ear, "Put your cameras and luggage in the compartment.

Come out with me. Don't carry anything."

And

so we did. She slipped her arm through mine; the other women And

so we did. She slipped her arm through mine; the other women

latched on to Ahmad and Shirin. With

arms full of flowers, acting as if we were lovers reunited, we

walked right past that long line of soldiers. Some gave us knowing

nods, as if to say, "Hey, you guys - you lovers - have a

great time! We won't bother you. Get along! Get on with it!" latched on to Ahmad and Shirin. With

arms full of flowers, acting as if we were lovers reunited, we

walked right past that long line of soldiers. Some gave us knowing

nods, as if to say, "Hey, you guys - you lovers - have a

great time! We won't bother you. Get along! Get on with it!"

Right:

Tanks in the streets outside

the citadel gates of Baku's Old City, January 1990. Photo: Reza.

No matter how nerve-wracking that experience was, even more unsettling

was the realization that a number of plainclothesmen had been

traveling on the train with us. When they got off, they flashed

their IDs to the soldiers and immediately started motioning some

of the passengers over to the side. It was so well organized

and well orchestrated that it was frightening.

A car was waiting for us. We went to dinner at someone's home.

It was a wonderful meal, especially after traveling for two or

three days with little to eat. It was good to be in Baku. Friends

of Ramiz Abutalibov (now with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

and Elinora gathered round that night. Ahmad wanted to film them.

"No way, man!" they replied. "Come on! We'll get

caught.

You can't film us. We're just here to talk about these things

and take you to different places." They knew how important

our mission was and were committed to getting the story out to

the world. They showed us a map of the city, pointing out exactly

where everything was happening and where the troops and tanks

were located.

I remember the TV blasting away in the living room. The chief

commander of curfew, a Russian, droned on, trying to convince

everyone that everything was under control - that nothing was

happening. Everybody ignored his platitudes; we all knew better.

We only got about two or three hours of sleep that night. All

evening we talked and talked, making plans.

I'll never forget how sad everybody was. I've visited more than

85 countries in my lifetime, but I would have to admit that during

those days, Baku was the saddest city I had ever seen in my life.

The people were in a daze, totally shocked and disoriented. It

was incomprehensible to them that the Russians had orchestrated

an attack on them and killed innocent people. After all, they

had been taught for 70 years about the great brotherhood of the

Soviet Union.

Just Like a Divorce

But in the midst of all that sadness, I detected another phenomenon.

It seemed people realized that the Soviet Union was collapsing.

An analogy could be made to living with a spouse and finally

reaching the decision that it is time to divorce. This feeling

of separation and desire for independence somehow seemed to give

the nation dignity in the midst of its despair over the loss

of so many friends and family members. It was like Azerbaijanis

had made up their mind to move on. That they knew what to do.

That the decision had been made.

During the first demonstrations, Azerbaijanis had sought better

relations with the Soviets because they believed in the relationship.

After Black January, they knew the relationship was over.

The Assignment

The next day, two cars came - one for me, the other for Ahmad.

We split up in case one of us got caught. Besides, it was hard

to operate in a small car and still conceal our cameras. Ahmad

had a HI 8 Sony video camera, which was small enough to fit in

his hand. I had two cameras; one smaller, the other larger. I

always left one of them at home in case the other got confiscated,

stolen or broken.

First we headed off to the hospitals. I'll never forget the horror

that filled those halls. The rooms were so crowded that the wounded

and dying were lying, unattended, in the corridors. We knew it

would be hard to get inside the hospitals undetected, since police

were guarding all of the entrances. I kept telling hospital personnel

that I was looking for a friend who had had surgery a few days

earlier. "He wasn't wounded," I explained. "It

has nothing to do with these latest incidents." Of course,

we didn't dare walk in carrying our camera equipment ourselves.

So one of "our scouts" would go in first, check the

place out and persuade some little old ladies-peasants-to come

out. We would stuff our bags down into their larger bags, and

off they would go walking right through the hospital entrance

for us.

We found it was safest to photograph inside the operating rooms.

Our scout would check if a room was safe. If so, we would slip

in and close the door. One of the surgeons told us that more

than 300 people had been killed and more than 1,000 wounded.

Unfortunately, many of those injured later died of their wounds.

After a few hours, we decided to head out in search of the tanks.

We found them in an open area, but it was impossible to photograph

without being detected. We hit upon the idea of taking photos

from an apartment opposite the parking area. One of our "scouts"

checked out the situation. Soon he was back and we were climbing

up to the eighth floor. Again, no cameras. Someone followed later

with our bags. But even though the view from the top was clear,

we knew it was too risky. The soldiers would have spotted us

too easily.

I decided to suggest that the lady of the house go out on her

balcony and pretend to be washing the windows. From inside, we

could then aim our telephoto lenses at the soldiers and tanks

below as she raised her arms to wipe the glass. Her body would

shield us from view. She agreed. It worked. We got the photos

we wanted.

Actually, our "cleaning lady" quite enjoyed the attention.

She kept saying, "I'm in a movie! I'm in a movie!"

It was all very funny. But her husband feared that the soldiers

would aim their guns at the apartment, or that someone would

come up and arrest him. Innocent people were being shot on their

balconies those days.

Down in the streets again, I knew I had to make every photo count.

I was deliberately traveling very light and had only seven or

eight rolls of film. Soldiers were patrolling the streets. Tanks

rolled by. Looking up at the apartments, we could see black strips

of cloth hanging down, symbolizing solidarity with those who

had died. Black was all over the place. It seemed the Azerbaijanis

were not afraid of making such symbolic protests. To me, it was

another sign that the Soviet Union was disintegrating - nobody

seemed afraid to offend the government anymore. Clearly, it marked

the end of the Soviet era. Everyone sensed that the end was coming.

In my opinion, the day those tanks entered Baku sealed the death

sentence for the Soviet era. Of course, it would take about two

more years before that great colossus would come tumbling down,

but clearly its legs were beginning to collapse.

Next, we went to a morgue. Again, the entrance was blocked. This

time they were checking IDs and writing down the names of everyone

who came in to identify the bodies. But there was one room that

we managed to enter. On a table in the center of the room there

were photographs of the corpses. People came in, picked them

up in their hands, with dread, desperately searching for their

loved ones, but at the same time, hoping not to find them there.

We learned that on the next day there would be a huge gathering

at Shahidlar Khiyabani (Martyr's Lane) as there would be a mass

burial. It would give us the chance to be among the people, to

witness their emotions. We knew we would be able to photograph

freely. It didn't even matter if the guy standing right next

to us was KGB or not. He wouldn't dare cause any trouble for

fear of being attacked by the masses.

But we knew not to take chances. We knew we would have to disappear

before the crowd dispersed so no one could follow us. We even

organized a little escape scenario. After the cemetery scenes,

we felt we had enough photos. We had already spent three days

and two nights in Baku. It was time to leave.

I don't quite know how our friends managed it, but soon we had

fake entrance visas along with tickets for the flight back to

Moscow. Officially, remember, we had not really entered Azerbaijan.

As with everything else that had happened in Baku, we had to

put our total trust in others, even to be able to leave the country.

As before, we didn't dare carry our cameras, videos or film with

us on the plane. We were told someone on the plane would carry

our equipment for us. We didn't know who. Enroute, however, two

Russian girls came up and started talking to us. We were suspicious

since we had heard so many stories about blonde Russian girls.

"Oh no," we told ourselves. "It's the KGB! They've

finally caught up with us." One girl spoke Azeri and made

reference to film. We totally denied knowing anything that related

to photography. "What film?" we asked. But it turned

out these were the passengers doing us the favor of carrying

our stuff in their suitcases for us. They had really given us

a scare.

Back at the Moscow Hotel, we got the film from the girls and

headed straight for the airport. We also found out what had happened

to the journalists who had taken the flight to Baku.

Just as I had suspected, none of the journalists had succeeded

in reaching Baku. It seems that when the plane was in mid-air,

flying over Caucasus mountain peaks, the pilot announced that,

unfortunately, Baku's airport had been shut down, and he would

have to divert the plane to the nearest airport. How convenient

that this airport just happened to be Yerevan (Armenia), where

the Soviet press had already arranged for newly arriving Armenian

refugees fleeing Azerbaijan to tell the international media their

version of how savage Azerbaijanis were.

Once again, the Soviets had duped the international press. The

only story that the press could take back home was exactly the

one that the Soviets wanted them to tell, which further justified

the need for troops to crush those unruly Azerbaijanis. The realization

gradually dawned upon us that not a single journalist had succeeded

in getting to Baku except us.

Looking back on those days in Baku, I'd have to admit that despite

all of my years of working in difficult places, I was terribly

afraid that something would happen to us in Azerbaijan - that

somehow we would disappear. After all, we were witnessing events

and gathering information that the whole Empire was denying,

and that the whole world was waiting to hear. We were the only

ones who were carrying the story out.

When the plane took off from Moscow, we all looked at each other.

I'll never forget the incredible relief and joy that was in our

eyes. It had been a tough seven days. We were finally taking

off for Paris. I couldn't believe we had made it.

Back in Paris

We landed about 4 or 5 that afternoon. Ahmad and I both sped

off to process our film and edit the videos. The news would air

at 8 pm. I was still afraid that maybe our films had been X-rayed

or the videos demagnetized. The Soviets were notorious for such

things. You think everything is fine, but when you arrive home,

everything is blank. I had heard the horror stories of a French

team who had filmed in Kazakhstan for three weeks. Upon arriving

home, they discovered that all of their tapes had been demagnetized.

They had nothing.

The TV was on at the lab when I started processing the slides.

Then I heard a voice announcing that at 8 o'clock there would

be a very important news broadcast. Tears came to my eyes. It

meant Ahmad's videos were safe. That night, the news opened with

the tragic events that were unfolding in Baku. They gave five

or six minutes of coverage, an incredibly long time by Western

standards, when the usual item runs 30 seconds to a minute.

My slides came out fine, too. I selected about 40 of them to

be duplicated for distribution. I gave them to an agency that

would transmit them to 2,000 magazines and newspapers all over

the world.

And so it was: 24 hours after we returned home, the tragic story

of Azerbaijan's Black January was being distributed around the

world. More than 18 TV channels and dozens of radio stations

were calling us for footage. Mission completed. Black January

was no longer a secret - the world was watching.

______

Note about Author in 1998: For the past 20 years, Reza has covered

every major war and conflict in the Middle East except Chechnya.

His works are published by some of the most reputable news agencies

and magazines in the world, including Newsweek, Time, Paris Match,

Stern and National Geographic.

The day we were going to press with this issue (mid-April 1998),

Reza was on his way to Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

and Thailand on a 10-day tour, accompanying Bill Richardson,

the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. The New York Times

Magazine had commissioned Reza to cover the Richardson's trip.

Footnote December 2002: Reza is currently in Afghanistan involved

with training Afghanis in media. He also has just made a film

with Sebastin Junger about Afghanistan. Contact Reza at reza@webistan.com.

___

Back to Index

AI 10.4 (Winter 2002)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

And

so we did. She slipped her arm through mine; the other women

And

so we did. She slipped her arm through mine; the other women