|

Winter 2002 (10.4)

Pages

50-51

Literary Transitions

No More

"Russian Language Trampoline"

by Shaig Safarov

Russian, though still widely in use in Azerbaijan, is not

the prestigious language it once was. And when it comes to translations,

Russian is no longer the "trampoline" from which all

works must spring. These days, Azeri is translated directly into

English, French, German and other languages and vice versa. There

is no middle language - Russian - as there used to be. Markets

are changing.

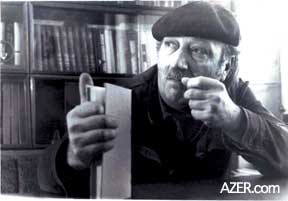

Left: Vladimir Gafarov was famous for his

translations of Azeri literary works into Russian (Courtesy:

Vladimir Gafarov family). Left: Vladimir Gafarov was famous for his

translations of Azeri literary works into Russian (Courtesy:

Vladimir Gafarov family).

A cold room. A man in

his sixties, jacket draped over his shoulders, is sitting at

his desk in the editorial office of the influential Russian newspaper,

"Bakinskiy Rabochiy" ("Baku Worker" in Russian).

It's a new position for him. Vladimir Gafarov became Deputy Editor-in-Chief

of this leading newspaper out of necessity. He'd rather be translating

poetry or writing it himself, just as he did in the past.

Gafarov is one of the grand patriarchs of Russian translation

in Azerbaijan. But language usage is shifting today, and this

literary giant who worked for so many years to refine his language

skills finds himself scrambling for a job. "Translation,"

says Gafarov, "is hard work, but it's generally satisfying.

Translating poetry is much more difficult than fiction. The translator

himself must have poetic inclinations, a sense of rhythm, and

a comprehensive lexical knowledge of both languages."

Translation used to pay well. Gafarov used to live a quiet, secure

life. Today, he makes about 170,000 manats (approximately $40)

per month. His wife's pension is 100,000 ($22). "Is it possible

to live on so little money?" he asks.

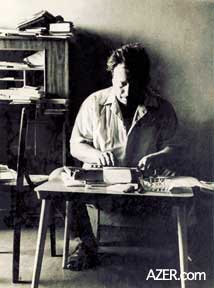

Left: Since Azerbaijan gained its independence

in 1991, there has been less and less demand for translations

of Azeri literary works into Russian. Here Vladimir Gafarov at

work (Courtesy: Vladimir Gafarov family). Left: Since Azerbaijan gained its independence

in 1991, there has been less and less demand for translations

of Azeri literary works into Russian. Here Vladimir Gafarov at

work (Courtesy: Vladimir Gafarov family).

On his desk are eight

books of poetry ready to be published. They're significant works

- some of the best in Azerbaijani literature, such as the epic

of Koroghlu, the works of poetess Mahsati Ganjavi (late 11th

centuryearly 12th century), and those of poets Molla Panah

Vagif (18th century), Vahid (20th century) and Fuzuli (16th century).

Gafarov is especially fond of Fuzuli. He's convinced that there

are not any good translations of Fuzuli's work in Russian. "Reading

some of Fuzuli's poems in translation is like chewing on a boiled

potato. I can't say whether I've succeeded in expressing his

philosophy or not, but at least my translations are readable."

Gafarov has also been busy translating a collection of "bayati",

2,500 lines in total. "Bayati" is a very old poetic

form (perhaps more than a thousand years old) and one of the

most difficult genres to translate. It consists of only four

lines, and as with Japanese verse, this succinct form is very

meaningful and popular amongst Azerbaijanis. According to Gafarov,

few people in the world even know of the existence of this form

in Azerbaijan. He has collected many of the elegiac and sorrowful

"bayati" that reflect the recent events that have befallen

the nation - topics like the war, its victims and martyrs, refugees,

and the struggles of life.

But these days, it's extremely hard to publish any books at all.

Gafarov quotes Anar, the President of the Azerbaijan Writer's

Union, who has often said, "In the past, you became a rich

man after you published a book. Today, you have to be a rich

man to publish a book." Not only is the price of paper extremely

high, but for Gafarov, the number of Russian-language readers

in Azerbaijan has seriously diminished.

He used to work for the "outer market", meaning works

for export outside of Azerbaijan but within the boundaries of

the USSR. In the past, many of his translations were published

in Moscow or Leningrad. But since the collapse of the Soviet

Union, all of the Republics are tending towards using their own

native languages, not Russian. It's a new day for the former

Republics of the Soviet Union. With priorities changing, and

markets changing, too, it's important for them not to completely

discard the past in their rush to embrace the future. A literary

legacy is at stake.

Update - December

2002

Shaig Safarov provides an update on language and alphabet issues:

These days, the Russian language

continues to die a slow death in Azerbaijan. Both Russian and

the Cyrillic alphabet are being used less and less, including

the modified version of Cyrillic, which was used for writing

the Azeri language for much of the Soviet era (1920-1991). The

first evidence of this tendency began in 1990-1991, even before

we had gained our independence when a few of Azerbaijan's newspapers

dared to challenge the Soviet system by printing their mastheads

in Azeri Latin script though the general text remained in Cyrillic.

Azerbaijan's Parliament officially adopted the Azeri Latin alphabet

on December 25, 1991, a few short tumultuous weeks after the

collapse of the Soviet Union. In fact, it was one of the first

items on their legislative agenda to revert to a similar Latin

- modified alphabet that had been in use during the mid-1920s

prior to the time when Stalin imposed the Cyrillic alphabet.

Obviously, the decision had political ramifications.

By 1992, the state TV station [AZ TV] presented its Azeri language

captions and headlines in the Latin script, not Cyrillic. Other

channels, such as the privately-owned ANS-TV, were quick to follow

suit.

Gradually, most Russian TV programming was dropped. Now only

a few Russian music programs on independent channels are aired

targeting teenagers. Nevertheless, one should underestimate their

tremendous appeal and influence.

The next major change came in the mid-1990s when street signs

and nameplates on official government buildings were replaced

with the new Latin script. In place of Russian names and Azeri

written in the Cyrillic alphabet, the Latin script was used for

Azeri and very often English replaced Russian. But old habits

die hard and, in general, Cyrillic continued to dominate, especially

in terms of common usage.

However, the transition to Latin simply did not happen in reality

until President Heydar Aliyev, with the backing of Parliament,

made a decree mandating that all signage and all official documents

had to be written in the Latin script by August 1, 2001. Only

then did Baku get a real face lift. Store owners complied despite

some reluctance.

Most signs in Russian, English or Azeri Cyrillic disappeared.

This is the reality that exists today. No longer do the street

signs and store fronts of Baku look like a Tower of Babel of

languages and alphabets as they did only two short years ago.

Nowadays, Azeri is the only language used at official meetings,

except when VIPs from Russia or other former Soviet republics

attend as officially invited guests. On such occasions Russian

is the lingua franca. It's obvious that Russians are a bit miffed

when they attend our international conferences and discover that

English has superseded Russian for many such occasions.

Likewise, all legal documents must be written in Azeri Latin.

Not long ago, I wanted to get a document printed in Azeri Cyrillic,

but the printing company refused, insisting that it was illegal.

The most recent stage in this tortuous journey of alphabet transition

has been the standardization of an Azeri Latin computer font

in UNICODE, which enables both IBM and Mac computers to communicate

with each other. As idealistic as that may be, unfortunately,

the reality is that many people don't have new - enough computer

systems and programs and so UNICODE is still not widely used

though this is, undoubtedly, the wave of the future.

Another trend is evident these days as well. Azerbaijani writers

who are more fluent in Russian are seeking good translators to

turn their novels into Azeri, an ironic twist from a decade ago.

Many translators have also found another way to make money -

by dubbing movies. Almost all of the TV channels (both state-run

and independent) compete to broadcast Azeri versions of Hollywood

movies. It's a relatively good (and unexpected) source of income

for translators and actors. The going price for dubbing can be

$50-100 a day, a significant sum, considering that many people

can work more than a week or more to earn that amount of money.

Almost all Azerbaijanis acknowledge the necessity of learning

Azeri, although not everyone has done so. I've spoken to several

people who are unemployed who regret not knowing our official

national language. In fact, they're admit that not knowing Azeri

is probably why they are out of work. "Why don't you learn

it then?" I ask. "Too lazy," is the usual reply.

Yet, on the other hand, there are many Russians in Baku, especially

those in business or sales, who speak fluent Azeri. Russian speakers

used to have the advantage in getting hired for the best jobs.

Today, the tables are turned and native Azeri speakers are more

likely to get the choice positions. In many ways, the wider usage

of the Azeri language has come a long way in just a short decade

though, admittedly, not without significant loss of intellectual

knowledge and transfer to future generations.

Vladimir Gafarov, a poet himself

and a renowned translator of literary works from the Azeri language

into Russian passed away in July 2000. Though he produced many

translations into the Russian languages, some volumes remain

to be published such as selections from Koroghlu, Dada Gorgud

along with the poetry of Vagif and Fuzuli.

Shaig Safarov currently heads the Azerbaijan Association of Mountain

Regions Development (ADRIA) and is deeply involved with Azerbaijan's

literary community.

___

Back to Index

AI 10.4 (Winter 2002)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|