|

Spring 2003 (11.1)

Pages

48-53

Medieval Secrets of Health

Farid

Alakbarli: Researching Baku's Medical Manuscripts

by Jean Patterson

Left: Farid

developed an early interest in animal and plant life. Here at

age 11 with his parakeet. Left: Farid

developed an early interest in animal and plant life. Here at

age 11 with his parakeet.

At age 40, Dr. Farid

Alakbarli is already the leading authority on medieval medical

texts from Azerbaijan. In his research at Baku's Institute of

Manuscripts, he has studied hundreds of rare texts - most of

them written in the Arabic script - to learn how medieval doctors

used traditional medicine to treat their patients. Many of these

remedies have long since been forgotten.

Medieval physicians have much to teach us about medicine, Farid

believes. Their traditional approaches have the potential to

be used once again in modern medicine, once they have been properly

investigated and scientifically analyzed. To restore and disseminate

this lost knowledge, Farid has spent the last two decades reading

and translating medieval medical manuscripts. His discoveries

suggest that modern man still has much to re-learn about the

human body and how to enjoy optimal health.

When it comes to Azerbaijan's

Medieval Medical Manuscripts written in Arabic script, Farid

Alakbarli has a lot of "firsts" after his name. He

was the first to undertake serious, in-depth study of all the

medical manuscripts that are housed at Baku's Institute of Manuscripts.

This resulted in his compiling a catalog of 365 manuscripts.

Among his discoveries were the manuscripts of two previously

unknown Azerbaijani physicians: Abulhasan Maraghai (18th century),

Murtuzagulu Shamlu (17th century).

He was the first person in Azerbaijan ever to study the concept

of preventive medicine as it existed in medieval Azerbaijan,

especially as it related to lifestyle, nutrition, sports, control

of emotions, protection of the environment, medicine and pharmacology.

Left: The Institute of Manuscripts in downtown

Baku. One of Oil Baron Taghiyev's buildings constructed at the

turn of the 19th century. Left: The Institute of Manuscripts in downtown

Baku. One of Oil Baron Taghiyev's buildings constructed at the

turn of the 19th century.

Another of his "firsts"

was the study of natural medicines as described in medieval Azerbaijani

manuscripts. Before him, scholars such as I.

Afandiyev and Arif Rustamov had written descriptions about the

ancient history of Azerbaijan's medicine, but none had approached

this complex study by drawing upon both social and natural sciences.

Because one of his doctorates is in Biology, it enabled Farid

to be the first person to study the species of herbs, minerals

and animals as described in medieval Azerbaijani sources and

analyze them from the biological, medical, philological and historical

points of view. As such he has identified 256 species of medicinal

herbs that had been forgotten. Once these natural substances

have been tested experimentally and clinically, many can be included

in the armory of modern medicine.

In addition, he found 866 types of complex medicines (such as

tablets, pills, syrups), identifying their composition and describing

their medical properties. Though found in medieval Azerbaijani

manuscripts, they had never been analyzed scientifically before.

Farid was the first to propose that a new system of health protection

should incorporate both traditional Azerbaijani medicine with

modern scientific medicine. His ideas are summarized in various

books and articles in Azeri, Russian and English. Thanks to his

meticulous research, a new 1,400-term glossary (1992) exists

of medieval Azeri pharmacological terms. Such a glossary had

never been published before.

Below: Farid Alakbarli, 8,

with his grandfather Aghabeyli Aghakhan (1904-1980) in 1971.

Farid credits his grandfather with instilling in him a love of

history by telling him stories about famous kings, writers and

poets. Aghabeyli was a professor of biology, a geneticist, and

a Corresponding Member of the USSR Agricultural Academy Of Sciences,

an honor bestowed on only two Azerbaijanis during the Soviet

period. He created a new breed of buffalos, the Caucasian Buffalo

(now, called the Azerbaijan buffalo). His book "Buffalos"

was published in Baku, Moscow and Vietnam (in Vietnamese language)

Prior to Farid's research, no medieval

Azerbaijani medical books had been investigated, translated and

published. In 1989, he and his colleagues published "Tibbname"

(Book of Medicine by Muhammad Yusif Shirvani) which had originally

been written in an old style of Azeri that was in use when it

was first penned in 1712. This volume is now available both in

modern Azeri and in Russian. This publication enabled readers

for the first time to be able to access information about Azerbaijan's

ancient medicine, as a primary source. The book has already been

published twice - 50,000 copies each time - which is considered

a very large print run for Azerbaijan. Prior to Farid's research, no medieval

Azerbaijani medical books had been investigated, translated and

published. In 1989, he and his colleagues published "Tibbname"

(Book of Medicine by Muhammad Yusif Shirvani) which had originally

been written in an old style of Azeri that was in use when it

was first penned in 1712. This volume is now available both in

modern Azeri and in Russian. This publication enabled readers

for the first time to be able to access information about Azerbaijan's

ancient medicine, as a primary source. The book has already been

published twice - 50,000 copies each time - which is considered

a very large print run for Azerbaijan.

Farid's most recent "first" comes this year, 2003,

when he published for the first time a book about ancient Azerbaijani

medicine in Russia (St. Petersburg). Along with his colleague,

Akif Farzaliyev, the medieval treatise, "Tuhfat al-muminin"

is now available. This was the third book that Farid had published

together with his colleague in the Russian language.

The primary question that Farid has been dealing with for the

last 20 years is how human beings, as revealed centuries ago

in medieval manuscripts, learned to take care of their health.

In the process, he has gained the perspective of early medical

specialists to some of the major topics that scientists are interested

in today, such as the secret to longevity. Today's doctors tell

us to eat nutritious foods, exercise regularly and stay away

from unhealthy habits like smoking or eating too many sweets.

Medieval Azerbaijani doctors had their own theories about what

constituted good health; some of their ideas align with the accepted

advice of today, others differ radically. Did they know something

that we don't?

Most definitely they did, says Dr. Farid Alakbarli, a medical

historian who has studied hundreds of medical manuscripts written

between the 9th and 18th centuries. These ancient manuscripts

are housed at the Institute of Manuscripts in Baku.

Medieval doctors prescribed a wide variety of medicines made

from plants, animals and minerals. In his research, Farid has

identified 724 plants, 115 minerals and 150 animals that were

once used for medicinal purposes in Azerbaijan. Of these, 256

species of medicinal herbs had completely been forgotten. Farid

has also identified 866 types of complex medicines, such as tablets,

pills and syrups, and described their medical properties.

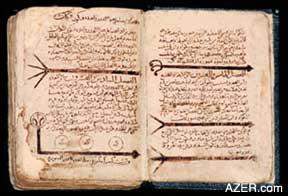

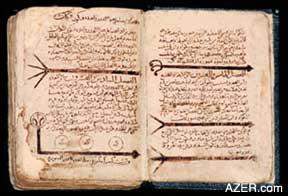

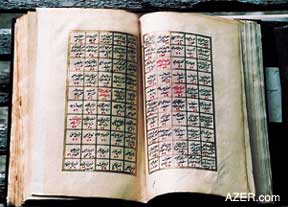

Left: From the 13th century text: "The

Book About Surgery and Surgical Instruments" by Andalusian

(the Arabic name for Spain during Mauritanian rule) Arab scholar

Abulgasim Zakhravi who was known in medieval Europe as Albucasis

and whose books were translated into Latin and taught in medieval

European Universities. Left: From the 13th century text: "The

Book About Surgery and Surgical Instruments" by Andalusian

(the Arabic name for Spain during Mauritanian rule) Arab scholar

Abulgasim Zakhravi who was known in medieval Europe as Albucasis

and whose books were translated into Latin and taught in medieval

European Universities.

What do doctors from

600 or 700 years ago possibly have to tell us that we don't know

already? Traditional medicine holds the key to untold advances

in treating and preventing disease, Farid believes. "If

we combine ancient knowledge with modern medical achievements,

we can arrive at a new concept of preventive medicine.

"People often ask me why ancient medicine is so important,

when we already have such strong modern preparations, like antibiotics

and sulfonamides. First of all, natural medicine, if used correctly,

doesn't have as many side effects as manufactured chemical preparations

do. Secondly, in some cases, herbs may even be more effective

than modern medicine. This is not to say that modern chemical

preparations are weak. On the contrary, they are able to kill

thousands of species of microbes. But an ax is less versatile

than a surgeon's knife. Herbal medicine is like a surgeon's knife:

it can be used precisely and gently because it is sufficiently

sharp and effective at the same time

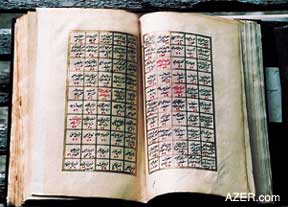

Left: The very informative pharmacology book,

"Karabadin" (Pharmacy Book) by Nuh Afandi written in

Turkish. Left: The very informative pharmacology book,

"Karabadin" (Pharmacy Book) by Nuh Afandi written in

Turkish.

"People often ask

me why ancient medicine is so important, when we already have

such strong modern preparations, like antibiotics and sulfonamides.

First of all, natural medicine, if used correctly, doesn't have

as many side effects as manufactured chemical preparations do.

Secondly, in some cases, herbs may even be more effective than

modern medicine. This is not to say that modern chemical preparations

are weak. On the contrary, they are able to kill thousands of

species of microbes. But an ax is less versatile than a surgeon's

knife. Herbal medicine is like a surgeon's knife: it can be used

precisely and gently because it is sufficiently sharp and effective

at the same time.

"Traditional medicine can be more effective than modern

medicine, with fewer side effects. For example, some doctors

treat urinary diseases with antibiotics and sulfonamides. However,

almost all antibiotics can result in mycosis [an infection caused

by a fungus] as well as many other diseases. Sulfonamides can

concentrate in the kidneys and lead to the formation of kidney

stones. On the other hand, herbal teas made of cypress cones,

chamomile and other herbs may be used to treat urinary diseases

without any negative side effects."

Left: Farid Alakbarli. The first time a medieval

treatise about ancient Azerbaijani medicine has been published

in Russia. Coauthored with Akif Farzaliyev. St. Petersburg, 2003. Left: Farid Alakbarli. The first time a medieval

treatise about ancient Azerbaijani medicine has been published

in Russia. Coauthored with Akif Farzaliyev. St. Petersburg, 2003.

Traditional medicine

is still very much alive in countries like Iran, Pakistan, India

and China. In some cases, healers treat diseases without the

use of medicine at all. For example, yoga can be used to treat

some nervous disorders through breathing and mental exercises.

For example, standing on one's head improves blood circulation,

enhancing memory and preventing sclerosis. Similarly, Chinese

healers use acupressure and massage to treat nervous diseases.

"But what does modern medicine do?" Farid asks. "Doctors

prescribe a lot of pills and infusions that aren't necessary.

Gradually, the patient loses self-confidence and becomes completely

dependent upon these drugs. He doesn't realize that he can help

himself by pursuing a healthy lifestyle, eating a nutritious

diet and getting regular exercise. Instead, he wakes up with

a capsule and goes to sleep with a tablet. This kind of psychological

dependence is very dangerous for the body and the soul.

"Many of the people who read my books try to use herbs for

self-treatment. For example, a famous historian was recently

complaining that modern medicine wasn't helping him. He asked

my advice about herbal treatment, so I recommended several herbs.

A week later, he called to thank me. His problems had been solved.

As it turns out, the herbs I had recommended were very effective,

whereas the enormous amount of antibiotics that he had taken

before had only worsened his condition.

There are many such examples." Azerbaijanis have a long-standing

tradition of using herbs as medicine. For example, many use chamomile

flowers to treat urinary and intestinal disorders. Valerian root

is well known as a sedative. "Unfortunately, people don't

always know the correct dosage or how to combine these herbs

with other herbs," Farid says. "Nor do they always

know which herb is the most effective in specific situations.

They drink the same herbs out of habit, without taking into account

differences in age, gender, weight or other important factors.

Therefore, the efficacy of the herb varies. In my books, I try

to explain the correct way of using these herbs, as portrayed

by medieval physicians."

Lifestyle for Longevity

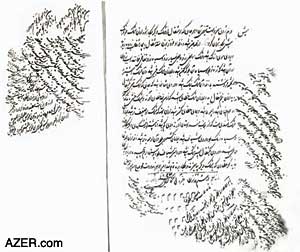

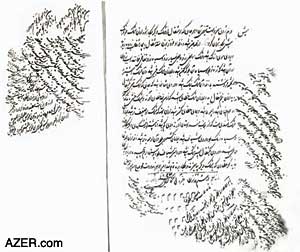

Left: Last page of a medical manuscript where

a copyist or reader added his own opinion or that of others in

related fields. Such practice was quite common in that day. Left: Last page of a medical manuscript where

a copyist or reader added his own opinion or that of others in

related fields. Such practice was quite common in that day.

Farid discusses medieval

conceptions of health in his extensive volume, "A Thousand

and One Secrets of the Orient," which was published in 2000

in Russian. This compendium of his work on traditional medicine

features an exhaustive listing of medieval prescriptions. In

ancient Eastern philosophy, he says, the emphasis was not so

much on treating diseases as it was on preventing them from occurring

in the first place.

One of most important sections of the book relates to diet. "Modern

dietitians tell us not to eat animal fat because it contains

harmful cholesterol," Farid says. "And yet, many Azerbaijanis

who eat meat and animal fat live to be a hundred years old or

more. How is this possible?

"According to ancient traditions, the secret is to eat meat

in moderation along with fresh vegetables, in order to prevent

the assimilation of fat. As a result, the organism gets all of

the necessary elements and is not damaged. This proves that the

recommendations of ancient traditions and medieval medicine are

sometimes wiser than modern judgment."

Childhood Interests

How did Farid become interested in a field that was rarely studied,

yet which holds much potential? He says his passion for scholarly

work began in childhood. Farid grew up in Baku's Ichari Shahar

(Inner City), the medieval walled city that foreigners often

refer to as the "Old City." "I was surrounded

by minarets, ancient fortress walls and towers," Farid says.

"Maybe that's one of the reasons why I became so interested

in history."

Farid's parents are both scientists who work in the field of

genetics. Inspired by their example, Farid spent much of his

childhood reading books from the family's extensive library,

especially books on history and biology.

"I loved reading illustrated books about nature," he

says. "I would spend a lot of time at the zoo and at the

Baku Botanical Gardens, where I was fascinated by the various

kinds of exotic palms, orchids and cacti. I also kept a variety

of pets at home, such as parrots, fish, lizards and tortoises."

At age 11, he owned a parakeet - a little Australian Wavy parakeet,

Farid says. "These birds are small like sparrows, mostly

green, but sometimes blue or yellow. They are very common in

Baku and very cheap. This particular parakeet had obviously flown

away from its former owner and happened to land on my balcony.

I managed to catch him with a colander from my mother's kitchenware.

After a while, I realized that the parakeet seemed to miss the

company of other birds, so I bought a friend for him from the

ZooShop for 3 rubles (about $3). I ended up with a male and a

female. I put them in a cage together and made a little nest,

hoping that they would mate. But it seems they weren't interested,

even though I had diligently read a book on raising parakeets

and followed the instructions."

Farid's grandfather on his mother's side, Aghakhan Aghabeyli

(1904-1980), was also an academic, specifically a biology professor

and one of Azerbaijan's two corresponding members of the USSR

Agricultural Academy of Sciences. "My grandfather inspired

me because he was such a knowledgeable person," Farid recalls.

"He developed a new breed of buffalo, the Caucasian Buffalo

(now called the Azerbaijan buffalo). His book 'Buffalos' was

published in Baku, Moscow and in the Vietnamese language.

"My grandfather was a biologist, but he also knew the Arabic

script, Persian, German, literature, poetry, history and many

other things. Besides, he had artistic ability and could draw

and play the piano and tar. When I was young, he would often

tell me stories about history and the famous kings, writers and

poets of Azerbaijan."

When Farid was growing up, the official alphabet in Azerbaijan

was Azeri Cyrillic, which had been imposed by Stalin in 1940.

(Azerbaijan switched to the Azeri Latin script in December 1991.

See Azerbaijan

International 8.1 (Spring 2000). Search at AZER.com.

At that time, only the older generation knew how to read the

Arabic alphabet, which had been used from the seventh century

up until 1929. When Farid was nine or ten years old, his grandmother

Ruhsara began teaching him how to read in Arabic. Soon he was

able to read the older Azeri books in the family's library. Today,

Farid is one of the few Azerbaijanis in the Republic who is able

to read the Azeri handwritten manuscripts penned in the Arabic

script though, of course, Azerbaijanis who live in Iran, which

number approximately 25-30 million, would not have much difficulty

in reading Azeri in Arabic script.

School and Komsomol

As a student at Baku's No. 134 Secondary Russian School, Farid

excelled in subjects like biology, history and geography. However,

during the Soviet era, good grades were not enough. All young

people in the USSR between the ages of 14 and 29 were expected

to join the Communist Union of Youth, or Komsomol. This was a

prerequisite to joining the Communist Party.

"When I was in 10th grade, my classmates were all members

in the Komsomol, that is, except me," Farid remembers. "I

avoided it because I didn't want to attend those endless boring

meetings and listen to contrived speeches, verses and songs about

how great the Communist Party was and how wise and kind our 'grandfather'

Lenin was. My teachers used to ask me why I hadn't joined the

Komsomol like other 'good boys.' Usually, I would tell them that

I didn't consider myself to be ready for such a great honor and

responsibility. They would look at me in astonishment, suspecting

that surely I was jesting.

"Finally, they issued a stern warning that I would not be

accepted into the university if I didn't join the Komsomol. Despite

my aversion to things political, I had little choice if I wanted

to pursue an academic career. So I agreed. My acceptance was

granted on the last day before I graduated from high school.

However, I still tried to avoid attending the Komsomol meetings

as much as possible. Eight years later in January 1990 [Black

January], when the Soviet Army entered Baku and killed hundreds

of civilians, I took advantage of the opportunity, as did many

others, to protest the massacre by leaving the Komsomol officially."

Language Study

In 1980, Farid graduated from high school and began studying

biology at Baku State University. In addition to science, Farid

focused on learning foreign languages, especially Persian and

Arabic. He had already studied Russian, Azeri and English and

was studying the Arabic alphabet and the Persian language on

his own.

"I used to open the dictionary and memorize the Persian

words by heart," he says. "I also had an Arabic textbook

by Alasgar Mammadov that I studied step by step. I would bring

the textbook with me to the university so I that could read and

translate during my breaks between biology classes. Unfortunately,

the textbook was filled with Bolshevik propaganda about Revolution

in Arabic countries, Azerbaijan and Russia. So I read additional

books like the Koran. Along with my study at the Biology Department,

I also attended the two-year Persian courses at the Institute

of Foreign Languages. I successfully completed the course and

qualified as a Persian language teacher."

At that time, Azerbaijanis who were interested in religion or

foreign languages were under strict surveillance by the KGB.

"I was no exception," Farid says. "The situation

became even worse when some students and I formed an informal

club to discuss political and cultural issues. One of my classmates

was an informant for the KGB and I soon found myself in trouble.

Our group did hold lively discussions about the possibility of

independence of Azerbaijan from the USSR. [Azerbaijan did succeed

in gaining their freedom from the USSR in December 1991].

"In 1982, I was called in and interrogated. They threatened

me and told me to put an end to my anti-Soviet activity. I realized

that the situation was becoming dangerous not only for me, but

also for my parents and relatives. I felt like I had no right

to put them at such risk, so I immediately went home and burned

my diaries and notebooks in which I had written down my thoughts

about scientific, cultural and political issues. I was 22 at

the time."

Institute of Manuscripts

After graduating from the university, Farid decided to specialize

in the History of Science. Combining his education in Biology

and his knack for reading ancient scripts, he began working at

the Institute of Manuscripts that is under the umbrella of the

Academy of Science. Farid refers to the Institute as a "sacred

temple of science" because of its enormously rich historical

archive of about 40,000 works in Azeri, Turkish, Uzbek, Persian

and Arabic. Many of the manuscripts date back to the Middle Ages.

"I was only 22 years old when I began working at the Institute,

but I knew that I wanted to devote my life to serious research,"

Farid says. "I became the first person there to focus on

studying medieval medical manuscripts."

Farid approaches his research from a multi-disciplinary point

of view, which gives him a broader understanding of the medieval

texts. He has a well-rounded education, with a Candidate of Science

degree in Biology (1992) [equivalent to a doctorate] and a Doctor

of Science in History (1998) [equivalent to a post doctorate

degree]. When he studies manuscripts, he is able to analyze them

from the point of view of a historian, botanist, biologist, physician,

dietitian and linguist. At the Institute, Farid received advice

and guidance from a number of mentors, including Dr. Mohsun Naghiyev,

Nasib Geyishov and Muzafaddin Azizov. "Dr. Mohsun Naghiyev

was head of the Persian department when I first started working

at the Institute," Farid says. "He was such a kind,

rare person. He knew Persian fluently and helped me from a linguistic

point of view by explaining the meanings of words and teaching

me how to read the various styles of cursive Arabic script."

Nasib Geyishov, a specialist in poetry and Sufism, shared his

immense knowledge of how to translate accurately. "Geyishov

was the only person at the Institute who really understood how

to read the medieval medical texts," Farid says. "He

told me which manuscripts were the most important and advised

me on the best medieval and modern dictionaries and catalogues

to use. Despite that medicine was not his field of expertise,

he helped me read and translate many medical manuscripts."

Calligraphy expert Muzafaddin Azizov taught Farid the essentials

of Arabic calligraphy. "Studying the art of calligraphy

helped me learn to appreciate the beauty of medieval Eastern

culture," Farid says. "Calligraphy is an integral part

of Muslim culture, just as it is for the Chinese and Japanese.

In the Middle Ages, any educated person had to know how to read

calligraphy. I didn't set out to be a professional calligrapher;

I simply wanted to learn how to read and write the various Arabic

script styles. Thanks to Azizov's help, I can now read the medieval

texts written in various calligraphy styles more easily."

Political Stirrings

For many scholars, delving into manuscripts that were written

hundreds of years ago can be a welcome distraction from contemporary

political issues. But for Farid, the world outside was rapidly

changing. "It was the era of Gorbachev's Perestroika, and

we felt the fresh air of freedom," he says. "Nearly

all of the scientists from the Institute, including me, participated

in meetings of the Popular Front, which was demanding independence

and a solution to the Karabakh question. In fact, Dr. Abulfaz

Aliyev (Elchibey), the chairman of the Popular Front and the

future president of Azerbaijan, worked at our Institute. His

workspace was right next to my table.

"At the time, some of my friends and elderly relatives warned

me: 'be careful! You're working in a very dangerous place - the

Institute of Manuscripts. This institution is comprised of an

array of anti-Soviet elements, starting with Abulfaz Aliyev himself,

whose desk is next to yours!' But I wasn't afraid. On the contrary,

I was proud to work beside such a courageous person, even though

I often disagreed with the ideas and methods of the Popular Front."

Soviet Censorship

Before Farid started his research, none of the medieval Azeri

medical treatises had been investigated, translated or published.

Then in 1988, Farid translated Muhammad Yusif Shirvani's "Tibbname"

(1712) from old Turkish into both Azeri and Russian. Shirvani

had been a palace physician for the Shirvan Shahs.

Once the translation of "Tibbname" was ready for publication,

Farid encountered a major problem: the Soviet censors were not

giving their approval for publishing it.

"The editor cautioned us: 'this book begins with the words,

"Bismillahi rahmani rahim" (In the name of God, the

Merciful, the Compassionate). Such an invocation is politically

and ideologically incorrect because we live in an atheist Soviet

state. You must delete all references to Allah from the book.

You may retain it in only one or two places, if you agree to

type it, not in upper case, but in lower-case letters.'

"My colleagues Akif Farzaliyev and Mammadagha Sultanov and

I all felt that this kind of censorship was utter nonsense. How

could we possibly modify an historical text? Even though we were

not traditional Muslims ourselves, we were scientists and as

such, we were not willing to accept alteration of the text.

"Then the editor crossed out part of the book and said:

'We can't publish these chapters because they deal with astrology,

alchemy and magic, not about medicine. These are ridiculous superstitious

beliefs. We can't mislead our readers.' He still did not seem

to grasp the idea that as ancient text this was a historical

monument that should not be tampered with.

"The next day, the editor found even more shortcomings with

the book. 'We have to remove all of the offensive, crude words

from the text,' he announced. 'This medieval author was a shameless

person. What terrible words he uses to identify sexual organs!

How could you use retain such expressions in the text? Take all

of them out. Yes, the Russians in Moscow are used to such vulgar

words in their books, but we are still not as "civilized"

as they are.'

"After all these corrections, 'Tibbname' became a much smaller

book. We were still hoping that it would be published, but it

turns out that we were mistaken. Six months later, the editor

called us again and said: 'you must exclude these 10 chapters

from the book. All of them are about sex. We are a Muslim nation,

and we should not read such amoral things. If you want the book

to be published, you'll have to remove them.'

"By this time, we were fed up. We told him: 'First of all,

if we really are Muslims, why did you remove the word "Allah"

from the book? Half a year ago, you said that we lived in an

atheist Soviet state. What are you saying now? Secondly, Ibn

Sina, Razi and other medieval authors were also Muslims, and

they wrote about the treatment of sexual diseases. Furthermore,

Prophet Muhammad said many things about sex in his hadiths [collections

of wise sayings attributed to Muhammad by his friends after his

death]. Are we greater than the Prophet and these writers?' However,

the editor did not want to listen to us. Obviously, he was afraid

of pressure from his own bosses, both in Baku and Moscow."

As it turns out, the "Tibbname" translation was eventually

published, more or less intact with its full text. But not until

1990. Since then, the book has become very popular among the

Azerbaijani public, selling more than 50,000 copies in its first

edition. This is considered a very large print run for Azerbaijan

with its population of 7.5 million at the time. But we succeeded

and it marked the first time that Azerbaijanis could read firsthand

about their own ancient traditional medicine.

Discoveries

During his research at the Institute of Manuscripts, Farid has

uncovered several other rare medical manuscripts that had long

been forgotten. These texts were not included in the treasury

of books related to Azerbaijan's history; in fact, Farid was

the first person ever to include them in the scientific literature

of Azerbaijan.

One such text is "Mualijati-munfarida" (Treatment of

Separate Medicines) by 18th-century physician Abulhasan Maraghai.

In his book, Maraghai describes the treatment methods that were

used for all of the commonly known diseases of his time. The

title "Separate Medicines" refers to simple medicines

that are comprised of only use one compound. Similarly, 17th-century

physician Murtuza Gulu Shamlu wrote the book "Khirga"

(Apparel of the Sufi) to describe how to treat reproductive disorders.

A "khirga" is a humble cloak that was worn by traveling

dervishes. Shamlu was the only medieval Azerbaijani author to

devote much discussion to this topic (although such books in

neighboring Muslim countries were quite common).

Farid has also discovered two Persian medical manuscripts that

are not known to exist anywhere else in the world: "Arvah

al-ajsad" (Souls of Bodies) by Kamaladdin Kashani (possibly

14th century) and "Zakhira-i Nizamshahi" by Rustam

Jurjani (13th century). Both texts are very extensive books on

pharmacology, with hundreds of formulas and descriptions of plants.

"Zakhira-i Nizamshai" imitates the well-known Eastern

pharmaceutical book "Zakhira-i Krarazmshahi" (12th

century).

Challenges

Reading these medieval texts is never easy, even for someone

who grew up reading the Arabic script. For one thing, much of

the specific medical terminology can be difficult to translate.

In order to decipher a certain word, Farid may need to consult

a number of different dictionaries, both modern and ancient.

"I must be very responsible and precise," he says,

"because my readers may try to use these ancient recipes

for self-treatment." To help other medical historians decipher

the texts, Farid has compiled and published a dictionary of more

than 1,400 medieval Azeri pharmacological terms.

Any mistranslation could lead to disastrous results. Farid recalls

one colleague who mistakenly translated the phrase "recipe

for a depilatory" (getting rid of unwanted hair) as "recipe

against baldness." "One day when I was working at the

Institute," Farid says, "I heard a scream coming from

the corridor. When I stepped outside, I saw a completely hairless

man grabbing the throat of the translator. As it turns out, he

was someone who did research at the Institute and who had only

a mild case of baldness. He had bought the book, prepared the

formula and applied it to his head before falling asleep. The

next morning, all of his hair had fallen out! He was so enraged

that he came to our Institute with the book in his hands so he

could hit the translator with it."

Right now, one of Farid's goals is to gradually reintroduce the

findings of medieval doctors. "Unfortunately, we have no

laboratory at our Institute to really investigate the potential

of these plants and substances," Farid says. "Medical

institutions in Azerbaijan are still facing an economic crisis

so they are unable to collaborate. So, not all of these herbs

have been tested scientifically yet.

"We can benefit from the wisdom of our ancestors,"

he continues. "The secret is to find out what they were

thinking and then to test it out. Once these substances have

been clinically tested, we can start to include them in the armory

of modern medicine."

To read articles by Farid

Alakbarli in English and Azeri Latin, visit AZERI.org,

which includes more than 20 of his articles plus six "Scientific

Tales for Children". Farid currently has an article,

"Aromatic Baths of the Ancients," published in the

U.S. journal HerbalGram (No. 59). See HerbalGram.com.

Back to Index

AI 11.1 (Spring 2003)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|