|

For professional and amateur

archaeologists alike, Azerbaijan is still very much virgin territory.

When you consider the number and scope of ancient artifacts that

could be discovered here, it seems that present-day researchers

have barely begun to scratch the surface. Opportunities abound

to examine early human development, beginning with the Ice Age

and the dawn of civilization, up to the point when humans began

to settle down from nomadic, hunter-gatherer societies into an

agricultural-based lifestyle requiring less moving. Left bottom: Cart ruts on the Absheron Peninsula

are believed to pre-date the wheel.

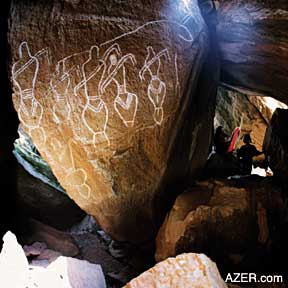

Already, international oil companies have begun carrying out archaeological studies in order to determine the impact that proposed pipelines will have upon the environment. Local and expatriate archaeologists have begun to explore various areas along the new oil BTC (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan) pipeline route, beginning at the Sangachal terminal, which is located within the larger scope of the Gobustan reserve, and running along some 1,700 km of pipeline through Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey. Their findings suggest that Gobustan is really just the tip of the iceberg, and that this entire area has the potential to provide us with a wealth of information about early humans. Pre-Wheel Technology  Our curiosity about early man was sparked by the cart ruts that Abbas Islamov and I discovered on the Absheron Peninsula. What were these strange parallel grooves? How were they used? Was this some kind of ancient roadway? When we first saw the tracks on the surface of the ground, it was difficult to figure out whether they had been manmade or not. Like so many clues about early life, the evidence can easily be overlooked by the untrained eye. But upon studying the cart ruts more carefully, we noticed that they all led from stone quarries directly to the sea. And they were clearly hewn out of rock by hand. Since then, we have learned that similar cart ruts can be found throughout the Mediterranean, along the seacoasts of Malta, Greece, Italy and southern France. Archaeologists hypothesize that cart ruts may date back as far as the Neolithic Age (10,0008,000 BC) or at least from the Bronze Age (5,0004,000 BC). It's quite likely that they predate the invention of the wheel. Some scholars suggest that the cart ruts themselves were lubricated, which would have enabled sledges, laden with heavy limestone blocks, to have been dragged from quarry to distant building sites. Below: left: This stone was probably lying horizontal in the past, but then fell on its side. Some holes are large enough to hold a sufficient amount of water. Other holes cannot yet be explained. Myriad questions remain. Right: Petroglyphs at Gobustan which date back between 5,000 to 10,000 years ago.

What exactly was being built back then, you may ask? Since the water level of the Caspian would have been much lower during certain time periods, we suspect that there are sunken buildings located along the Caspian shoreline that would provide clues if only they could be investigated. At least such construction has been found in other countries. But we have yet to prove our supposition. [For more on cart ruts, see "Cart Ruts and Stone Circles: Key Evidence from the Past is Endangered" in AI 10.3 (Autumn 2002). Search at AZER.com.] Discovering the cart ruts spurred us on to head to the hills during our leisure hours, in search of more evidence of prehistoric man. Even as passionate amateurs, there's so much that we can do to locate, identify and even begin to interpret some of the features at various sites. And most of all, we hope to stimulate scholars to get involved in research projects here in Azerbaijan. Below: five photos: Cupmarks are believed to have been made by man during the Stone Age period. So many questions remain. Why are some cupmarks larger than others? Why are some round, while others are square? Why are some connected wtih channels, while others aren't? Why do some of them always appear with the same design across a vast territory? Why are some of them found on top of mountains? Why...why...why?  Identifying the locations of these sites on a map is critical for their protection and for the heritage of the country. Sadly, in Azerbaijan, as elsewhere in the world, ancient Stone Age monuments can easily be damaged and destroyed - often unwittingly by stone quarry workers or developers. For example, the world-class petroglyphs of Gobustan were discovered quite by accident in the 1950s when quarry workers started to drill into some of the boulders that provided cave shelter for these early inhabitants. Once an ancient site is lost, it can never be replaced. Information about the whereabouts of these landmarks is essential, particularly for planning and development purposes. But this information will only be made available if Azerbaijan's Ministry of Culture - whose responsibility it is to protect national monuments - can provide sufficient resources. The more we discover, the more we see the necessity for developing a national database of archaeological sites and implementing effective protective measures. Education and awareness programs are essential so that the Azerbaijani public can appreciate and value the ancient heritage that is located right in their own backyard. Signs of Ancient History

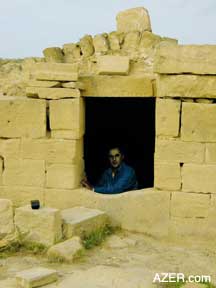

Throughout the months we concentrated on locating likely sites based on location, rock formations and an elevated sea level explorations, we have found abundant evidence of what we believe to be Stone Age and Bronze Age sites and settlements. So far, we've focused on coastal areas from the Absheron Peninsula to Besh Barmag (Five-Fingered Mountain) north of Baku, and then inland to the region of Shamakhi and down to Alyat. Many of these sites, like Gobustan, reflect a time when the level of the Caspian Sea was higher than it is today. At first, when we were hiking through the fields and hills, it was hard for us to discern any evidence of early man. Quite soon however, we began to learn what to look for, and started identifying patterns of settlement. It helped to consider where ancient peoples would have looked for shelter, especially for protection from the prevailing north wind.  It's also quite easy to locate sites and artifacts in areas where the soil is thin. Semi-desert soil conditions are especially helpful. We've found many sites located inland. With thin soil or a rocky landscape, everything is exposed and easy to find. In other areas where the soil has built up, evidence is buried and harder to find. Take the cart ruts, for example. In some areas, these are quite , but we are aware that the ruts continue for several tens of meters due their imprint on the land. Here in-filled channels act as water traps and so support various types of vegetation. Stone Age Artifacts Although the cart ruts are a significant find, we've also discovered various stone circles, megalithic boulders, caves and rock dwellings. There are many structures related to ancient tombs, such as simple stone mounds, more elaborate round barrows, long barrows and chambered cairns - mounds of stones which are erected as a memorial.  Since stone is virtually indestructible, the artifacts that we've come across have probably remained unchanged, and perhaps even untouched, down through the ages. Objects like a discarded flint shard or a stone mallet may have gone untouched by a human hand for several thousand years. It's fascinating to think that some of the sites we've stumbled across are like time capsules, just waiting to reveal their secrets. Stone technology was certainly robust and prevalent for a long period of time. No doubt that's why archaeologists have named this era the "Stone Age." However, this term is a bit of a misnomer, since stone artifacts were still being used well into the Bronze and Iron ages. At the same time, ancient humans obviously did not rely solely on stone. No doubt, early man was also skillful in creating tools out of other materials, such as bone, wood, antlers and leather - all of which would likely have disintegrated long ago. Many of the stone features that we've come across are depressions or holes that have been bored out of boulders and outcrops. These include rock holes for cooking, water channels and pot holes, possible sacrificial holes, site markers, tethering points, and - for want of a better term - holes that are termed "cup marks." Obviously, these features were manmade and served a certain purpose. But many of them mystify us. What were they really used for? Some are easy to understand and interpret; others are more enigmatic and pose riddles that have yet to be solved. In any case, it may be a long time before they are understood - if ever. Water Channels and Pot Holes  Today it's hard to imagine the coastal landscape of Azerbaijan at a time when Gobustan was inhabited, but without a doubt, it was an era when the level of the Caspian was much higher, due to water that melted during the Ice Age. This, in turn, means that the low-lying hills we see today would likely have appeared as small islands. As such, many would have lacked natural flowing streams. Early man had to use his ingenuity to catch and store rare and precious rainwater. By carefully studying the rocks in these areas, we've discovered that he was quite adept at it. However, it should be noted that there were periods of time during the ice ages, when the sea level would have been much lower than it is today. Evidence of human occupation from those periods would be hidden from view today. For instance, we've seen channels that were strategically cut into the limestone surface to capture the water and then direct it to collection holes, or cisterns, or possibly a collection vessel such as a leather or clay pot. These systems were so effective that they continue to function today, benefiting both wildlife and trees. For example, we've seen birds drinking from these same holes, leaving their telltale signs of nutrient enrichment to the benefit of a particular orange lichen that is common to the region. In some locations where a channel sheds off a rock, perhaps aiming at one time for a collection vessel, trees can now be found growing and thriving. Access to the water traps was not always simple. Sometimes the sloped rock that was used for water collection was too high for humans to reach. Consequently, they built primitive stairs to reach it. Water channels are often found next to rock shelters or caves. Channels and pot holes are simple ideas that - at least in one case - have been adapted by later residents. At a site to the north of a ruined caravanserai in the Gobustan-Gizildash region, we came across a vaulted arched building that turned out to be a modern cistern. Located in front of the cistern is what appears to be a water collecting system from the Bronze Age. Three major water channels lead into the building, which contains a water pit that is about 2m x 5m x 1m. The pit has been cut into the limestone and is accessible via a stairway. We feel it is reasonable to assume that this well-designed building, with its intriguing entrance and overflow pipe, may have been constructed as a watering hole for Silk Road travelers. This cistern - apparently unknown to Azerbaijan's Institute of Archaeology - merits detailed investigation, as it bears witness to an obvious technological link to the distant past. We know that early man used fire to cook and keep warm. This is apparent from the number of hearthstones and ceilings covered with smoke in the rock shelters that we have found. But the question remains: without metal pots, how did early humans heat water? The answer is simple. From the site at Gobustan, we know that they made holes in the rocks, filled them partially with water and then added hot stones from their fires. Such holes are a prime feature of settlement sites. We've also found water holes that were apparently for animals. One example was specifically set up so that a goat or horse could be tethered and thereby prevented from wandering away. The thoughtful owner had had the foresight to provide a nearby supply of drinking water for the animal. Holes for Sacrifices At each settlement site, it's common to see a rock with a depression and two short channels running into it. These holes are typically found on rocks that are quite flat. We've also noticed that such patterns are often located at a slight distance from the settlement and sometimes even overlooking it. As the channels leading into the hole are rather short, it seems unlikely that they were related to water collection. Rather, we think that they may have had some practical use associated with collecting liquids - perhaps for milking animals or collecting the blood of a sacrificed goat or lamb. Perhaps these sacrifices were made as offerings to the gods. Curiously, the design of the channels leading to the holes appears to be consistent, meaning that there is a great likelihood that some ritual was associated with them. In every case, the channel on the right is relatively straight, whereas the one on the left has a distinct bend or angle to it. Wine Presses We've also found evidence that early man had a taste for refined beverages and was actively engaged in winemaking. Simple rectangular - shaped grape presses cut from the bed rock have been found on the Absheron Peninsula at the cart rut site near the town of Turkan. It's difficult to say how old these presses are. They may only date back a few hundred years, but the fact that several of these presses were found suggests a thriving industry, and perhaps an ancient practice. According to Dr. Idris Aliyev of the Institute of Archaeology, the soil on the Absheron Peninsula is ideal for vineyards and, indeed, you find many of them there today. Apparently the Absheron area - and in particular, the site of the old village of Absheron, located in a military area near the town of Dubendi - may well have been a center for winemaking. Burial Sites As in most societies, early humans in Azerbaijan took special care of their dead and built special structures for their burial. At one of these vaults, we saw two holes drilled through the end wall. Dr. Victor Kvachidze of Azerbaijan's History Museum identified these holes as being used to allow the spirits of the deceased to leave the burial chamber and enter the afterlife. This indicates that early inhabitants had a spiritual dimension to their lives and deep - rooted religious beliefs. This comes as no surprise, for in Azerbaijan - a land full of mystery, fire and mud volcanoes - religious practices can be traced back to antiquity. On another expedition, we found a tomb made of limestone slabs, which dated back to the Bronze Age. Originally, it had a capstone and was buried below soil and stone to form a small round hillock or mound, called a barrow. Unfortunately, grave robbers opened the tomb long ago and stole any artifacts that were inside. Grave robbing is a serious concern today. The artifacts found inside could provide invaluable information about the life and habits of early man. But the people who rob and destroy these graves are instead depriving Azerbaijani society of its heritage and history. This is all the more reason why these sites need to be identified and protected. Cup Marks The patterns that we call "cup marks" have been difficult to interpret. Generally, these examples date from the Stone Age and are simple, fairly hemispherical depressions 2-10 cm in diameter and 3 cm deep. These kinds of cup marks have been reported throughout Europe in association with megalithic sites. They've been found on large boulders, rocky outcrops and on a number of separate cup-marked stones. We have found them in great abundance here in Azerbaijan. Often they appear in groups. In one case, we found more than 100 indentions appearing in a random pattern on a single stone. Some cup marks even appear on the sides of stones and boulders, which makes it even more difficult for us to figure out exactly what they were used for. Obviously, they could not have been used to hold objects or liquid. Some of the literature about European cup marks associates them with Bronze Age burials or cult practices, but we have not been able to find a definitive answer as to what they were really used for. Perhaps they served a variety of purposes. It is equally possible that they may date to later eras than the time when the megalithic site was first used. Still, the multitude of cup marks at Azerbaijan sites leave us intrigued and baffled. Border Markers Some cup marks can be found on rather remote, yet prominent stones in the settlement. Perhaps these indentations served as border markers. In this category, we have grouped holes into two distinct types: those found on the tops of hills and others found on outlying rocks in open areas. There is clearly some logic in marking such prominent spots. Unlike a stone mound or cairn, which can easily be damaged or destroyed, a cup mark is permanent and, if searched for, can easily be found. These cup marks may have served as a signal that the territory was occupied. Link to Spirit World Another interpretation of the cup marks is that they were associated with burials. According to Dr. Farid Alakbarov, medieval medical texts indicate that pulverized material from ancient stone was believed to cure disease. Similarly, a small bag filled with stone fragments or powder taken from the grave of an ancestor or another holy place may have served as a talisman. Perhaps individuals carried the stone dust with them at all times, as a reminder of their heritage and of the community to which they belonged. According to Alakbarov, the "Tibbname" (Book of Medicine), which was written in 1712, documents centuries - old cures, including the belief that consuming powdered stone from a grave marker served as a remedy against falling in love. Being "too much in love" was perceived as a form of madness, as depicted in the legend of "Leyli and Majnun", a story similar to "Romeo and Juliet" but which preceded it in oral tradition by at least 1,000 years. According to Alakbarov, the very fact that this superstition was recorded in the "Tibbname," a medieval book written in an Islamic environment that rejected beliefs in spirits, powers, fetishes and idols, tells us how widespread the tradition was. To comprehend the "cup mark" phenomena, we have to understand one thing very clearly: the "Other World" - the world of spirits, "deceased", "powers" and "ghosts" - was perceived as being absolutely real for ancient people. In turn, these cup marks are markedly concentrated at or around burial places, whether they be mounds, stone circles, cairns or dolmens. These are the sacred places where the "powers" or "energies" were believed to be the most concentrated. Cup marks also seem to be associated with places that were not related to burials, but served religious or ritualistic purposes. These include standing stones, temples and other places that had sacred meaning. Untapped Riches Much has yet to be learned about Stone Age, Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeology in Azerbaijan. Clearly, these untapped archaeological riches need to be identified, protected and studied. For us, as amateurs, getting out into the countryside to make observations and take photographs is proving to be a very worthwhile, enjoyable and fascinating pastime. We do feel, however, that with the right level of protection, and the wealth of techniques available to modern archaeologists, the history, ancient lifestyles and development of man in this region will become demystified. This is a challenge that cannot be undertaken by Azerbaijan alone. It will require considerable involvement and resources, not only from the Azerbaijan government, but also the international community. We are sure the Institute of Archaeology would welcome such offers of support. We think there's a story here to be told. How significant it is to our understanding of early man, only time will tell. Ronnie Gallagher has been working

in Baku for the past several years as BP's Environmental Manager

in Baku. Abbas Islamov has been Safety Advisor at BP for the

past four years. They both have been involved with BP's Archaeological

Baseline Survey in relationship to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline

currently under construction. Contact Ronnie Gallagher at: gallagher_ronnie@yahoo.co.uk;

contact Abbas Islamov at: abbasislam@msn.com. Back to Index

AI 11.1 (Spring 2003) |