|

Spring 2003 (11.1)

Pages

33-39

The Church in Kish

Carbon

Dating Reveals its True Age

by J. Bjornar Storfjell,

Ph.D

Other articles

by or related to Bjornar Storfjell:

Thor

Heyerdahl's Final Projects - Bjornar Storfjel (AI 10.2, Summer

2002)

Voices

of the Ancients: Rare Caucasus Albanian Text - Zaza Alexidze

(AI 10.2, Summer 2002)

The Kish Church:

Digging Up History - Bjornar Storfjell (AI 8.4, Winter 2000)

An interview with J. Bjornar Storfjell

When archaeologists come upon discoveries

hidden in the earth, it often takes time to research and make

comparative studies in order to truly comprehend them. At first

glance, for example, they can identify a piece of pottery, but

it may take months or even years of further research to fully

appreciate its significance. When archaeologists come upon discoveries

hidden in the earth, it often takes time to research and make

comparative studies in order to truly comprehend them. At first

glance, for example, they can identify a piece of pottery, but

it may take months or even years of further research to fully

appreciate its significance.

The same holds true for the Kish Church Project near Shaki in

Northwestern Azerbaijan, a project that was undertaken so that

the architecture could be restored. In the meantime, the archaeological

knowledge gained is helping fill in some of the blanks related

to the development and spread of Christianity via Albanian Caucasian

churches.

The archaeological dig at the Kish church took place in the summer

of 2000. In August, the results of carbon-14 dating on four samples

were made available. Now, nearly three years later, scientists

have had a chance to do some comparative studies. The results

are somewhat different than expected. The church building, as

it turns out, was built more recently than previously thought.

Instead of being erected in the 5th or 6th century, Carbon-14

dating places it very likely in the 12th century (990-1160 A.D).

In addition, the church building itself was discovered to have

undergone architectural alterations that reflect theological

shifts, brought about by the geopolitical realities of the day.

For example, the belief in the nature of Christ (whether he was

fully man and / or fully God) is reflected in the height of the

floor of the area in the church (the chancel) where the priest

officiates in relationship to where the congregation stands.

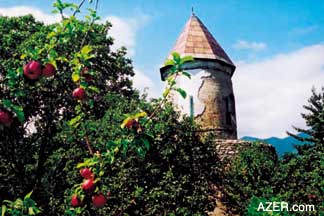

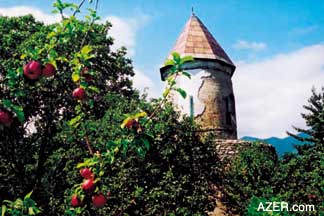

Left: Kish Church near the town of Shaki

in the Caucasus. Archaeological work was done to determine its

age before reconstruction work began. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell) Left: Kish Church near the town of Shaki

in the Caucasus. Archaeological work was done to determine its

age before reconstruction work began. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell)

Also the archaeological

dig at Kish revealed evidence of the Early Bronze Age culture

known as the Kur-Araz culture, which originated in the Caucasus

region about 3500 B.C. This culture is known to have spread both

northward as well as southward across Anatolia as far as Syria,

Israel and Palestine, and possibly even to Egypt.

But more significantly, the site on which the church was built

suggests that prior to Christianity, it was a cult site that

dates back 5,000 years (3,000 years prior to the beginning of

Christianity). The fact that this site was used for earlier belief

systems is not an unusual phenomenon for sacred sites throughout

the world.

We've written about the Kish project before when we interviewed

archaeologist Bjørnar Storfjell in the summer of 2000

and featured him in an article in our winter issue that year,

"The Kish Church, Digging Up History." Search at AZER.com.

Now that the results are back from carbon dating, new interpretations

can be made.

The Kish Church

Actually, you have to go quite a distance out of your way even

to find the place. From Baku, Azerbaijan's capital, on the western

seacoast of the Caspian, you drive about five hours northwest

to the charming, picturesque city of Shaki, located in the foothills

of the Caucasus Mountains. From there, the Kish village is about

five km further north on a poorly marked road with broken pavement.

It takes some maneuvering to manage all the ruts. The small village

is located about 1,200 meters (3,600 feet) above sea level on

a small ridge between two branches of the Kishchay (Kish River).

Left: Interior view of the dome of the Kish

Church. Archaeologists date the original construction of the

church to around the11th or 12th century. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell) Left: Interior view of the dome of the Kish

Church. Archaeologists date the original construction of the

church to around the11th or 12th century. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell)

In general, the village

is rather non-descript, with its houses constructed of gray river

stones. The dull color, however, beguiles the nature of the people

who are really quite hospitable and cheerful.

Similar to many small mountain villages, agriculture and animal

husbandry comprise the backbone of the local economy, but many

of the villagers try to supplement their income with work in

Shaki. In the summer of 2000, the only obvious employment in

the village was the construction of a new mosque.

The Kish church sits on a relatively large plot of land, especially

given its own small physical size.

In fact, the building is actually taller than it is wide. No

homes are built close by. The church itself is really small and

spartan in both its architectural design and detail. In North

Syria, there are more than a hundred churches that bear close

resemblance to this one in Kish that were constructed between

the 4th and 7th centuries and that are found in the smallest

of hamlets and villages. You probably can't fit more than 25-50

people inside them - and that's with everybody standing, as was

the custom of the day. Churches didn't have seats or pews back

then. In Azerbaijan, there are a number of Christian churches

much larger and much older than this one in Kish.

The idea for the Kish Project originated with Bjørn Wegge

of Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise of Oslo, who himself had

done graduate work in Early Church History in the Eastern Church.

His cultural interests coincided with those of Olav Berstad,

who was the Norwegian Ambassador to Baku at the time. Berstad

himself had been professionally trained as an archaeologist.

Between the two of them, the concept for the project soon took

on a life of its own. Berstad felt that the more the newly independent

nation of Azerbaijan could establish direct links with its past,

the more Azerbaijan would be able to strengthen its national

identity as a separate entity in the Caucasus.

Below: Left and Right: Storfjell consulting

at excavations at the Kish Church.

The idea was to restore the

Kish church architecturally and convert it into a museum, which

would then be dedicated to the early church history of Caucasus

Albania - the region that now is known as Azerbaijan. The project

developed into a joint Azerbaijani-Norwegian effort under the

direction of Dr. Gulchohra Mammadova, Rector of the University

for Architecture and Construction and a Member of Parliament.

However, before reconstruction was to begin, archaeologists were

consulted to try to establish the date of the church and determine

if there had been any early stages of construction or use. Dr.

Vilayat Karimov of Baku's Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography

served as the Director of Excavations. Archaeologists included

Aliya Garahmadova of the same institute, Suseela C. Y. Storfjell

of the University of Sheffield, England. I served as archaeological

advisor for the project. The actual archaeological dig was carried

out in two sessions: June 5 - July 3, 2000, and then two months

later from September 4-13.

Left: The Georgian priest who came to conduct

a service at the Kish church while the archaeologists were excavating.

It seems this may have been a long-standing tradition, even though

there were no parishioners. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell) Left: The Georgian priest who came to conduct

a service at the Kish church while the archaeologists were excavating.

It seems this may have been a long-standing tradition, even though

there were no parishioners. (Photo by Bjornar Storfjell)

Archaeological excavation

was concentrated mostly inside the church, although a few trenches

were dug outside along the north and east side of the apse (the

rounded end of the church) [see sketch]. Other trenches were

opened in front of the church entrance on the west end and along

the south and southwest sides.

Inside the church, we began our investigation along the north

wall just in front of the chancel steps (the raised platform

area where the priests officiate). We soon discovered, however,

that we were not the first to carry out some excavation there.

After digging down about 1.5 meters, we were surprised to come

upon an artifact of quite modern origin - namely, a size D battery

manufactured in Japan. It was clear evidence of a spent flashlight

of recent date, and the unmistakable traces of treasure hunters

- either robbers or bootleg archaeologists! We asked the villagers

if they knew of anyone who might have been digging around in

the church, but no one seemed to have any knowledge of it. Nor

did anyone at Baku's Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography,

the institution responsible for coordinating all archaeological

activity throughout the country.

Of course, on sunny days, the diggers would not have needed any

artificial light to dig inside the church. However since they

were tunneling under the chancel floor, they obviously needed

light to see what they were doing, as the trench was about four

meters long (12 feet), much of it under the flooring. They had

dug to a considerable depth below the foundation of the church,

well into what archaeologists term "sterile soil,"

meaning soil that has not been modified from its original state.

Left: Architectural

rendering of Kish Church. (Photo by Gulchohra Mammadova) Left: Architectural

rendering of Kish Church. (Photo by Gulchohra Mammadova)

Then the culprits had

refilled the trench. However, when it comes to archaeological

investigation, such cover-up work can easily be detected, even

if the soil has been packed down very hard, which it hadn't been.

During the weeks that followed, our imaginations worked overtime

trying to think who might have intruded. Soon our speculations

became a source of tales and jokes that lightened the grind of

everyday excavation work. In the end, we never did learn who

had been digging there. Oh, if only walls had eyes to see and

tongues to speak!

We were quite eager to begin excavation in the northern half

of the apse. To do so meant that the altar would have to be dismantled.

But then a Georgian priest appeared on the scene, wanting to

perform a liturgy. After all, he was just carrying on the intended

use for the church, despite the fact that there were no parishioners.

He only came once while we were working there. We explained to

him what the duration of the project would be, both in regard

to excavation, as well as to its architectural restoration. If

he had been in the habit of stopping by more frequently at the

church, we were not aware of it. He seemed pleased to learn about

the restoration work.

And so the priest conducted a brief liturgical service while

we stood there in silent reverence of that sacred moment in time.

The darkness inside the church was accentuated only by a few

rays of sun penetrating through the slits in the cupola. There

in the darkness, the clergy's face was illuminated by candle

flame. His voice echoed through the stone vaulted interior of

the old stone structure. It didn't seem to matter that his words

were unintelligible to us; they still had the power to transport

us back to a different era in time.

Soon afterward, we got back to work, excavating the altar to

see what might lie beneath it. Archaeology requires that whenever

any monument is dismantled that it should first be carefully

recorded and photographed as it originally stands. In this case,

the plaster was carefully removed so that the stones could be

numbered, a process that would facilitate its reassembly.

Below: right and left: A coin from the 6th

century, featuring Sasanian King Kavad I was found in the excavation

of the Kish church. (Photos

by Bjornar Storfjell)

Generally, archaeologists can

expect to find a reliquary (a box with a relic that relates closely

to the person or the saint) buried underneath the church altar,

especially if the place of worship has been named or dedicated

after an individual or a saint. We found no such evidence at

Kish. Instead, beneath the altar lay irrefutable evidence of

an Early Bronze cultic sacrificial pit, yielding secrets of ceramic

fragments, charcoal, charred bones and two skulls of sheep or

goats. The carbon dating eventually yielded up the secrets of

the pit, dating the contents to around 3000 B.C.

Kur-Araz Pottery

Left: A sample of Kur-Araz pottery that dates

to the 3rd century B.C. was found underneath the altar of the

church and suggested the site had been used as a cult site 5,000

years ago. (Photo by Bjornar

Storfjell) Left: A sample of Kur-Araz pottery that dates

to the 3rd century B.C. was found underneath the altar of the

church and suggested the site had been used as a cult site 5,000

years ago. (Photo by Bjornar

Storfjell)

Our first clues that

something was buried under the altar came when we realized that

the soil in the pit had a different color and texture. Near the

bottom of the pit, we came across some ceramic fragments buried

in the dark, ash-like soil.

After the ceramic fragments had been cleaned and reassembled,

we identified it as a small jar that belonged to what archaeologists

call the Kur-Araz culture [Kura-Araxes in Russian]. It was handmade,

not turned on a potter's wheel. Its base was smaller than the

opening of the jar. This term Kur-Araz in archaeology designates

the culture in the watershed region of these two rivers in the

Caucasus that dates back to the 4th and 3rd millennia B.C.

In the Eastern Mediterranean world, these same ceramic forms

that originated in the Caucasus and showed up later in the 3rd

millennium B.C. are known as Khirbet Kerak Ware, having been

named after the archaeological site on the southwestern shore

of the Sea of Galilee in Israel, where they were first discovered

in the 1960s. Such ancient pottery found in countries quite distant

from the Caucasus such as Syria, Lebanon, Israel and (Amiran

1969: 68-69) is recognized as a foreign cultural phenomenon,

with no local roots. Much more research is needed to trace the

stages of this cultural migration of ceramic forms from the Caucasus

southward into Iran and southwesterly through Anatolia and along

the Eastern Mediterranean coastline.

This same Kur-Araz culture also migrated north of the Caucasus

and was found in the Guba (Kuba via the Russian language) region

and also in Dagestan of Southern Russia (Kushnareva 1997:44).

It appears that in the Early Bronze period, in the 4th and 3rd

millennia B.C., the Caucasus (Trans-Caucasus via Russian) was

the cradle of a culture that spread in all directions. More research

is needed to understand the development of this cultural diffusion.

Sixth-Century Coin

We also found other artifacts. For example, a silver coin was

found near the northeast corner of the apse. Unfortunately, it

was not recorded and photographed in situ, that is, in the very

spot where it had been found. Since it had been removed from

its immediate stratigraphic context before being recorded, the

coin provided less archaeological value than might have been

possible otherwise. The coin was quite legible, both on the obverse,

as well as the reverse, side. We sent a photo to Dr. Vesta Sarkhosh

Curtis, Curator of Parthian and Sasanian Coins at the British

Museum, who confirmed that the coin was a silver drachma featuring

Sasanian King Kavad I, who ruled from 488-496 A.D. and again

from 498-531 A.D. She figured out that the coin belonged to the

second period of Kavad's rule because the regnal year on the

left side of the reverse reads 39. The mint legend on the right

side of the Zoroastrian fire altar is Istakhr, a town about 5

km north of Persepolis in southwest Iran. The Pahlavi/Middle

Persian legend on the obverse reads "Kavad Apzud",

literally "Kavad Increase," or meaning "May the

Glory of Kavad Increase."

Below: (two photos)In a burial at the entrance

of Kish church were various artifacts, dating back to the 13th

century, including a small cross made of mother-of-pearl and

numerous strands of gilded thread, possibly from clerical robes

and an embossed gold piece, possibly from a belt or sash used

in clerical attire. (Photos

by Bjornar Storfjell)

If it could be ascertained that the

coin had come from the construction phase of the church, it still

would only have provided us with the earliest possible date for

construction. In reality, coins and their mint dates are not

the best indicators of the age of the soil layer in which they

were found. In a study that I carried out with James Brower in

the early 1980s, we showed that coins are reliable for dating

only about 40 per cent of the time (Storfjell and Brower 1982). If it could be ascertained that the

coin had come from the construction phase of the church, it still

would only have provided us with the earliest possible date for

construction. In reality, coins and their mint dates are not

the best indicators of the age of the soil layer in which they

were found. In a study that I carried out with James Brower in

the early 1980s, we showed that coins are reliable for dating

only about 40 per cent of the time (Storfjell and Brower 1982).

That means you would have a greater chance of being correct by

simply flipping the coin. At least then you would have a 50-50

chance of being right! It is, however, fairly safe to conclude

that someone had been in the Kish area perhaps in the sixth century

or early seventh century and had simply lost the coin. Again

it must be stressed that the very limited scope of our excavations

leaves us with so many unanswered questions as to who that person

might have been and what kind of activities might have been carried

out in Kish at that time.

In all, we organized four specimens

to be tested for Carbon-14 analysis at the Beta Analytic in Miami,

Florida that August 2000. One sample was taken from the charcoal

found in the pit. Since the charcoal came from the ash-like soil

that was found among the charred bones and the broken ceramic

jars, we assumed it might provide a likely date that would identify

the period of the cult sacrifice and the pottery. In all, we organized four specimens

to be tested for Carbon-14 analysis at the Beta Analytic in Miami,

Florida that August 2000. One sample was taken from the charcoal

found in the pit. Since the charcoal came from the ash-like soil

that was found among the charred bones and the broken ceramic

jars, we assumed it might provide a likely date that would identify

the period of the cult sacrifice and the pottery.

When collecting samples for carbon dating, it is necessary to

use extreme caution since false readings can occur in the process

if the specimens are contaminated. For example, since this form

of testing is based on the decay of carbon radioactivity, samples

cannot be wrapped in any type of organic material, such as plastic,

which is an oil derivative, meaning that as it was made of a

petroleum product it contains radiocarbon itself. So we wrapped

the four samples that we wanted to test - bone, charcoal and

two soil samples - in a mineral derivative-aluminum foil - and

placed them in bottles that had caps separating the plastic with

tinfoil.

We organized for the samples to be taken from the site early

one morning when we began excavation. People had been told the

day before that we would be gathering the samples, since no one

would even be permitted to smoke when we extracted them. Nor

did we touch the samples with our hands, but rather coaxed them

into the containers using the metal tip of the trowels.

Left: Dr. Vilayat Karimov of Baku's Institute of Archaeology

and Ethnography served as the Director of Excavations. Here he

points to pottery shards that were identified as Kur-Araz pottery

of the 3rd century B.C. (Photo by Bjornar

Storfjell) Left: Dr. Vilayat Karimov of Baku's Institute of Archaeology

and Ethnography served as the Director of Excavations. Here he

points to pottery shards that were identified as Kur-Araz pottery

of the 3rd century B.C. (Photo by Bjornar

Storfjell)

The radiocarbon analysis

on the charcoal in the pit beneath the altar was 4500±40B.P.

(Beta-157479) with a 13C to 12C ratio of -23.7. The 2s calibrated

result representing historical dates was 3360 to 3030 B.C. with

a 95% probability. This analysis thus corroborates the ceramic

analysis that we would make, lending strong support for the pit

dating back to the Early Bronze Age (circa 3000 B.C.).

This meant that already three millennia before Christianity was

founded, the site upon which the Kish church would be built,

was being used for sacrifices - as a cult site. Actually, it

is quite a common phenomenon that cult sites, where sacred rituals

previously were carried out, often retain their sacredness, even

though religious form and content may change through the ages.

Thus, many churches throughout the world, not just the Kish Church,

have been built on the remains of earlier sacred sites.

Because of the limited scope of our excavation at Kish, we unfortunately

have no further archaeological evidence to understand what might

have been going on there during that era. This intriguing question

awaits further archaeological work in the village.

Floor Level

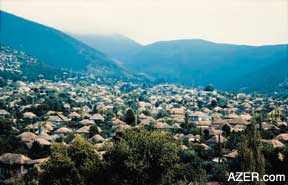

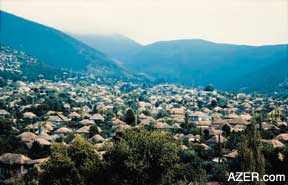

Left: The town of Shaki lies in the foothills

of the Caucasus about five hours northwest of Baku. Kish is a

village about 5 km distance further up in the mountains. (Photo

by Oleg Litvin) Left: The town of Shaki lies in the foothills

of the Caucasus about five hours northwest of Baku. Kish is a

village about 5 km distance further up in the mountains. (Photo

by Oleg Litvin)

We also suspected that

excavating the chancel area might give us a clearer picture of

the various phases that the church might have been used for over

the centuries. This turned out to be the case: alteration of

the level of the flooring, indeed, was evident and indicated

a modification in theological belief.

In the nave, we discovered that the church represented two different

periods of use, with two different corresponding floor levels.

From the apse we know that when the church was first built, the

floor in the chancel was only between 30 and 40 cm above the

level of the floor of the nave. Later it would be raised to about

one meter (100 cm) above the floor of the nave.

What is of interest is the presence of two significantly different

levels for the floor in the chancel. In the Eastern Church, the

theological debate concerning the nature of Christ raged on between

the 4th and 5th centuries and was not officially put to rest

until the Council of Chalcedon in 451 A.D. Later various national

churches aligned themselves with one position or the other. The

question that concerned them dealt with the nature of Christ

- his deity and his humanity: Was Christ only divine, but manifest

in human form, or was He fully divine and fully human at the

same time? In church history, this debate came to be known as

the monophysite vs. diophysite struggle (one nature vs. two natures).

In churches that reflect a belief in Christ as being diophysite

- the floor level between the chancel where the priest officiates

and where the worshippers stand is closer. In other words, the

priest, who is Christ's representative on earth, is in closer

proximity to the worshippers. This idea reflects the belief that

Christ was God but also fully human. In contrast, in churches

holding onto the monophysite belief, the chancel is built at

a higher elevation.

In the Caucasus, three national churches arose during this period,

and in the debate related to the nature of Christ, only the Georgian

Church followed Constantinople [Istanbul] and the Council of

Chalcedon, which settled the Christological debate by pronouncing

in favor of the dual nature of Christ - the diophysite position

(Ferguson 1997:233). There seems to be some evidence that the

Caucasus Albanian Church also remained within the diophysite

tradition but only until early in the eighth century (Alexidze

2002:27). After that time, the monophysite doctrine prevailed

in both the Armenian Church and the Caucasus Albanian Church

(Lerner 1999: 212 and Di Berardino 1992:18).

Since the architecture of the apse of the original church in

Kish suggests a diophysite Christology, and since the Georgian

Church was the only diophysite church existing in the Caucasus

in the late medieval period, it seems reasonable to suggest that

the Kish church was built as a Georgian church and was later

taken over by monophysites. The remaining three radiocarbon dates

also seem to favor such an interpretation.

Charcoal Sample

We chose the second sample for carbon dating from some charcoal

taken from the lowest soil layer in the nave. Since there was

only sterile soil below this sample, it would represent the time

period of the construction of the original church, when the area

would have been cleared for that purpose. The result of the analysis

of the sample was 980±40B.P. (Beta-157480) and the 13C

to 12C ratio was - 25.3. The 2s calibrated result representing

historical dates was 990 to 1160 A.D. with a 95% probability.

Bone Samples

The other two samples were bone fragments from two burials that

relate to the construction of the church. Outside the church

on the eastern side of the building, we found a series of burials.

Curiously, the lowest burial in this sequence had caused the

builders of the church to make a small niche at the very bottom

of the foundation wall for the apse, no more than about 20 cm.

deep, to accommodate the skull of the burial. In digging the

trench for the foundation, the builders had come upon this burial,

and not wanting to disturb it, had made a small indentation in

the base of the foundation so the head in the burial would not

be disturbed.

The burial orientation with the head to the west and the feet

to the east, leads us to assume that the burial was Christian.

Its relationship to the foundation wall suggests that it was

already there when the church was built. The result of this sample

was 1000±40B.P. (Beta-157482) and the 13C to 12C ratio

was -19.1. The 2s calibrated results representing historical

dates were A.D. 980 to 1060 and A.D. 1080 to 1150 with a 95%

probability. In this situation the first set of dates, A.D. 980

to 1060, represent the better curve, since the 1sigma limits

fall within those dates, while the second set represents a "shadow."

Thus the first set of dates is the one preferred.

That would seem to suggest that the burial could have been nearly

a century earlier than when the church was built, possibly early

in the 12th century. Again, historically this fits very well.

It was during the expansion of Georgia under the rule of King

David the Builder (1089-1125 A.D.), when nearly all of the territory

from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea was under Georgian influence

(Alexidze, October 11, 2001 and Allen 1971:96-100). Thus, the

architectural elements that reflect theology point to a Georgian

church. Chronologically, the radiocarbon dates do the same.

Dr. Zaza Alexidze of the Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts of

the Georgian Academy of Sciences in Tbilisi, Georgia informs

us that the general area of Kish remained under Georgian suzerainty

until the 17th century, when the Persian Shah Abbas wrestled

it from Georgia and established the "Sultanate of Elis"

(Alexidze, October 11, 2001).

Theological Questions

It is probably quite safe to assume that it was the diophysite

theology of the Georgian Church that was followed and reflected

in the architecture in Kish, since the area was under Georgian

political control. It would probably also be safe to assume that

as soon as Georgia no longer controlled the region, the Caucasus

Albanian Church, which since the eighth century, and possibly

earlier, had adopted a monophysite theology like the Armenian

Church, would make its theological position felt in regards to

the height of the chancel in the church.

We can then conclude that the remodeling of the church, elevating

the chancel from between 30 to 40 cm above the floor in the nave

to nearly 1 meter above the floor, took place sometime in the

17th century. Also, after the small enlargement of the chancel

area, the church remained a monophysite place of worship until

it ceased to be an active church in the 19th century. Perhaps,

this even explains the tradition of the visit by the Georgian

priest to conduct services despite the fact that he had no parishioners.

Therefore, the medieval literary tradition concerning the church

in Kish (and earlier oral tradition which cannot be verified),

repeated by several present-day scholars (Mammadova 2002: 34,

35, 38), cannot be given serious consideration. This tradition

suggests that the Kish Church was built at the end of the first

century A.D. If true, that would indeed make this a truly significant

church, since no church structures anywhere in the world are

known to have been constructed earlier than the mid- to late-third

century (Meyers 1997:1). To refer to the Kish church as the "Church

of St. Eliseus" (Mammadova 2002) is to attempt to give scholarly

credence to a medieval literary tradition whose date cannot be

substantiated and supported by archaeological evidence.

The fourth sample for carbon dating was a bone taken from a tomb

under the entrance to the church. The radiocarbon analysis gave

a result of 700±40B.P. (Beta-157481) with a 13C to 12C

ratio of -18.8 . The 2s calibrated results representing historical

dates were 1260 to 1310 A.D. and 1360 to 1390 A.D. with a 95%

probability. This situation is the same as the one encountered

with Beta-157482 and, therefore, the preferred dates are 1260

A.D. to 1310.

A mended glazed ceramic bowl from this tomb also suggests a late

medieval date. Other items in the grave clearly were related

to some high-ranking clergy in the early years after the construction

of the church. These finds consisted of a small cross made of

mother-of-pearl and numerous strands of gilded thread, which

very likely came from his clerical robes. There was also an embossed

gold piece, probably part of a belt or sash for clerical attire.

Cruciform Architecture

Even the shape of the church itself - the cruciform, or cross-in-square

appearance, known as quincunx - also suggests a date in the late

medieval period. Such designs are common in the Caucasus and

may even have originated in the region (Krautheimer 1965:245).

The Kish church only had the appearance of being cross-in-square,

while, in truth, it was really a rectangular building with an

external semi-circular apse at the east end. On each of the long

sides of the building, the architect had placed a small gable,

giving the appearance that the church was built in the shape

of a cross. At first we thought this was a feature added at the

time of a later remodeling or reconstruction phase. It now seems

certain to have been the original design.

Even with the rather limited scope of this archaeological project

related to the Kish church, significant finds and implications

for early history, including some of the ecclesiastical history

of the region, have come to light. It seems we have just been

served an appetizer and can only dream of the kind of archaeological

feast that awaits if more extensive excavations can be organized

in the village of Kish. That feast will have to come with future

projects.

Bibliography

Alexidze, Zaza, Tbilisi, Georgia to J. Bjørnar Storfjell,

Aylesbury, England, October 11, 2001. Personal communication.

___ "Voices of the Ancients: Rare Caucasus Albanian Text."

Azerbaijan International 10:2 (Summer 2002): 26-27, Sherman Oaks,

CA.

Allen, W. E. D. A History of

the Georgian People from the Beginning down to the Russian Conquest

in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul,

1932 and 1971.

Amiran, Ruth. Ancient Pottery of the Holy Land: From its Beginning

in the Neolithic Period to the End of the Iron Age. Jerusalem:

Massada Press, 1969.

Di Berardino, Angelo, ed. Encyclopedia

of the Early Church. Translated from the Italian by Adrian Walford.

Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1992. S.v. "Albania of

Caucasus," by M. Falla Castelfranchi.

___, ed. Encyclopedia of the

Early Church. Translated from the Italian by Adrian Walford.

Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1992. S.v. "Georgia,"

by M. Falla Castelfranchi.

Krautheimer, Richard. Early

Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Harmondsworth, Middlesex:

Penguin Books, 1965.

Kushnareva, K. Kh. The Southern

Caucasus in Prehistory: Stages of Cultural and Socioeconomic

Development from the Eighth to the Second Millennium B.C. Translated

by H. N. Michael. University Museum Monograph 99.

Philadelphia: The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania,

1997.

Lerner, Konstantin. "Georgia,

Christian history of." In The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern

Christianity, eds. Ken Parry, et al., 210-214. Oxford: Blackwell

Publishers, 1999.

Mammadova, Gulchohra (Mamedova).

"The Azerbaijan-Norwegian Kish Project: Progress Report."

The History of Caucasus: Scientific Public Almanac 2 (June 2002):

33-40.

Meyers, Eric M., ed. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in

the Near East. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press,

1997. S.v. "Churches," by Paul Corby Finney.

Ferguson, Everett, Michael P.

McHugh, and Frederick W. Norris, eds. Encyclopedia of Early Christianity.

Second edition. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc.,

1997. S.v. "Chalcedon, Chalcedonian Creed," by Frederick

W. Norris.

Sarkhosh Curtis, Vesta, London

to J. Bjørnar Storfjell, Tromsø, Norway, July 6,

2000. Personal communication.

Storfjell, J. Bjornar. "The

Kish Church: Digging Up History. Norwegians Help Restore Ancient

Church." Azerbaijan International (AI 8.4), Winter 2000,

pp. 18-21, Sherman Oaks, CA.

___, and James K. Brower. "The

Use of Coins for Findspot Dating." Paper Presented at Annual

Meeting of the American Schools of Oriental Research, New York,

New York. December 20, 1982.

J. Bjørnar Storfjell,

Ph.D., formerly professor of archaeology at Andrews University

in Michigan (1980-1999) and head archaeologist in the summers

of 2001 and 2002 of Thor Heyerdahl's final project to see if

there were any links between Scandanavia and Azov, Russia.

More recently, he has been appointed Chief Executive and Archaeologist

of the recently created Thor Heyerdahl Research Centre in Aylesbury,

England, created by Thor Heyerdahl to carry on his vision. Visit

THORHEYERDAHL.org. Contact Dr. Storfjell: jbs@thorheyerdahl.org.

n

___

Back to Index

AI 11.1 (Spring 2003)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|