|

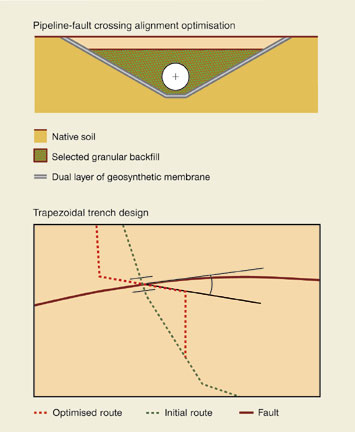

BTC's investment in the community strategy is also generating interest. In its commitment to Georgia, the BTC Company plans to make a number of sustainable environmental and social development investments worth about $6 million. Priority will be given to income-generating activities, renewal of rural infrastructure-such as schools, health clinics and village roads, the provision of fresh water and improved energy supply. These projects will be implemented by eight local non-governmental organizations, working with two international NGOs-Care International and Mercy Corps. An initial phase, designed to create trust, will concentrate on projects that have immediate impact such as refurbishing school buildings and other community-related projects. The second phase will focus on the longer-term sustainable development initiatives.  "BTC is not just about money and jobs," says William Townsend, BTC's Commercial & Reputation Assurance Manager based in Tbilisi. "It's about people. At every stage we have engaged and consulted. The result is a world-class project that factors in the concerns of its relevant stakeholders." Dealing with Earthquakes Earthquakes can happen anywhere, any time. In the last century, there wasn't a single year during which tremors were not recorded somewhere on the planet. At its simplest, an earthquake is the sudden release of strain energy in the earth's crust, resulting in waves of tremors that radiate outward from the source. When stress within the earth's crust exceeds the strength of the rock, a break occurs along the lines of weakness. The point where an earthquake originates is known as the focus or hypocentre, and may be many kilometres deep within the earth. The point at the surface directly above the focus is called the epicentre. Around 75 percent of the world's seismic energy is released along the edge of the Pacific in a 40,000 km band of seismicity extending up the west coasts of North and South America in an arc to northeast Asia. Another 15 percent is released along the Alpine-Himalayan band that stretches westwards from Myanmar to the Himalayas, the Caucasus and the Mediterranean.  The BTC pipeline will cross two distinct seismically active zones-as defined by magnitude and intensity-on its way from the Caspian in Azerbaijan and on through Georgia to Turkey and the Mediterranean. This entire region forms part of the Alpine-Himalayan fault and fold belt-a zone constantly being formed and deformed by the collision of the African, Arabian and Indian tectonic plates. Normally earthquakes are measured in terms of magnitude and intensity. The most common measure is the Richter scale, developed in the 1930s using data from seismograms. In simple terms, a quake with a magnitude of five on the Richter scale is equivalent to the explosion of 1,000 tons of TNT, while a magnitude of six is 30 times greater with the energy equivalent of 30,000 tons of TNT. An average year will see 20 earthquakes around the world measuring seven or more on the Richter scale. Magnitude is one measure of an earthquake's size-and as such remains unchanged with distance from the epicentre of the tremor. However, intensity which defines the degree of tremors caused by an earthquake at a given place decreases with distance from the epicentre. The scale of intensity spans from one (which is so slight that it is not felt) up to 12, which would describe total devastation. Various types of faults also exist, each having a specific type of relative movement between the tectonic plates. Wherever a pipeline crosses such faults, the relative movement between the tectonic plates may impose shear, tensile or compressive strains (or combinations of these) on the buried pipeline. Several active faults criss-cross the BTC link-including three in Azerbaijan, three in Georgia, and seven in Turkey. To design a safe route in these places, the BTC consortia has utilised the specialist skills of companies such as ABS Consulting and DJ Nyman & Associates which concentrate on the assessment of seismic hazards assessment and fault-crossing evaluation. Initially, the pipeline is routed across active fault lines following an alignment optimised from a construction perspective. Both the fault displacements and the initial pipeline alignment are then analysed to assess the strains induced on that line. Where these strains are deemed unacceptable, various mitigation measures are employed to reduce the strains to within acceptable limits.  These mitigation measures could include reducing the pipeline/fault-crossing angle to help promote tension and reduce compression in the pipe. Special material properties can also be designated for pipe that is used in fault-crossing areas. Where the fault / pipeline alignment results in a degree of lateral pipe/soil movement, a trapezoidal trench design will be used to reduce soil resistance either side of the pipe to allow it to move more freely-an essential measure if large ground movements are to be absorbed safely. Another possible mitigation measure is the use of granular material for backfill and, in some cases, the inclusion of a geo-textile membrane to enhance the mobility of the pipe/trench material. A maximum trench depth is usually specified which must not be reduced by vehicular traffic. Other preventative measures include avoiding sharp changes in direction within the fault zone. Fair Treatment for all From the outset, it has been a core principle of the BTC and SCP projects that all affected communities and peoples be treated the same, regardless of ethnicity, language, religion or culture. Ethnicity, nationality and the status of religions have long been complex and sensitive issues in each of the three countries along the route. In addition, recent conflicts and civil unrest in the region have resulted in large flows of refugees and internally-displaced persons (IDPs). Some nine distinct ethnic groups have now been identified by language that live within two kilometres of the pipelines. These include Turks, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Armenians, Greeks, Russians, Belorussyans, Kurds and Circassians. Religious belief varies significantly by district and is mainly Christian (Orthodox) and Muslim (Shia, Sunni and Alevi). While governments have the main responsibility for safeguarding and promoting human rights, the BTC/SCP partners believe they can play an important role by promoting transparency in their operations and encouraging engagement with communities, governments and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Human rights, ethical behaviour and the prevention and resolution of conflict have been recurring themes in many discussions the consortia have held with local groups prior to the start of construction. Outside the region, public attention has been focused on Kurdish-speakers along the pipeline corridor. The BTC route avoids settlements where the majority of Kurds live. Villages within the pipeline corridor tend to be mixed, but a few are entirely Kurdish-speaking. Kurdish is the primary language in 0.6 percent of households and the second language in 7.5 percent. Very few of these households have ever seen Kurdish in written form, which is the major reason why Kurdish representatives express a preference for Turkish in negotiations and documentation of land agreements. Based on surveys of 1,737 households along the route, which BTC undertook as a part of the project's consultation and disclosure process, matters of concern to Kurdish-speakers are not related to ethnicity or language. Their inquiries are generally similar to those expressed by other groups-compensation for land and crops, opportunities for employment, and issues related to security. Although there are problems of poverty, unemployment and infrastructure in communities where the Kurds are living, our surveys indicated that these villages do not suffer disproportionately from these factors. Kurdish-speakers have been, and will continue to be, included in BTC consultation teams. BOTAS, the lead contractor on the Turkish section of the route, is employing Kurdish-speakers from northeast Anatolia as part of its land acquisition and community relations teams. Any demand for legal documents in Kurdish (or other minority language or dialect) will be handled sympathetically. Beyond this, community investment programmes in Turkey are to be targeted at communities most in need-many of which include Kurds. Protecting the Past Cultural heritage, in general, and archaeology, in particular, are issues of concern that unite the three countries along the BTC route. All three have seen the rise and fall of countless societies and civilizations. The first villages were established in Anatolia during the transition phase from hunter-gatherer to food production approximately 9000-5000 B.C. Georgia has sites dating back to periods long before written records began. Azerbaijan is rich in the remains of past societies with all stages of human development represented. All three countries have figured prominently in some of the world's most ancient east-west trade routes. Officials in each country recognize that significant archaeological sites are a non-renewable resource of prime importance. For some authorities, pipelines such as BTC appear to be a threat to such sites, especially in a part of the world where human habitation has such a long, varied and rich record. But pipeline construction also offers a unique opportunity for archaeologists to investigate areas in which little, or no previous work has been done. At first glance, the concerns of archaeologists and the demands of an ambitious industrial project such as a pipeline may seem at odds. Archaeologists normally work in a painstaking, labour-intensive, almost surgical way. Pipeline planners, on the other hand, use modern machinery and management techniques to progress at a fairly rapid pace of one kilometre a day or more under prime conditions. Balancing the requirements of both groups began many months ago. The first priority in route selection was to avoid known archaeological sites or unexplored areas of obvious interest. In Azerbaijan, early studies based on desktop research, interpretation of aerial photographs and physical surveys on the ground, suggested there were about 70 confirmed or potential sites along the corridor. Similar studies in Georgia identified 51 archaeological sites and more than 200 cultural monuments on the initial route, while in Turkey, field studies turned up 179 sites within a kilometre of the corridor. Re-drawing the original route resulted in the avoidance of many of these sites. In all, more than 100 archaeological and cultural locations, and eight nationally or internationally designated conservation areas have been avoided. Those sites that could not be skirted because of overriding environmental or engineering factors or those which presented complications because of their size were earmarked for further physical investigation such as the digging of trial pits. One such site was in the Tsalka region of Georgia, where local archaeologists and labourers, funded by BTC and supported by BTC technical advisers and logistics specialists, battled blizzards at the end of last year to ensure that the site was fully excavated before construction began in spring. Normally, such work would have been delayed until the warmer months of the year. The pipeline had already been diverted once to avoid an area of even greater archaeological interest; therefore, time was critical. Even when all known and suspected sites have been avoided or investigated and excavated before construction, archaeology still has a tendency to surprise-and particularly so when a deep trench has to be dug along a 1,760km corridor. Fortunately, professional "pipeliners"-generally a tough, no-nonsense lot-have a reputation for a light touch when it comes to sensing even small changes in the texture and consistency in the earth being uncovered in the trenches that they are digging. This touch, along with tell-tale signs of fossils, pottery shards and bits of bone, will be crucial for the BTC cultural monitors attached to each construction unit whose job it is to evaluate whether further investigation is needed. Should the monitors decide that such work is necessary, the construction teams will "work around" the site until excavations are completed or a minor re-route agreed upon. This is but one element in a five-step strategy designed to ensure that the archaeological benefits of the project outweigh any damage to the archaeological record. At every stage, BTC teams will be working closely with experts from institutions such as Azerbaijan's Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography (IAE). There will also be opportunities for training and technology transfer as well as the sharing of expertise among national and international specialists. Already this approach is bearing fruit. In Azerbaijan, IAE staff members have walked the entire 445 km route to the border with Georgia, registering any archaeological sites they found. "We must give our partners their due. In most cases, we managed to find enough evidence to re-route the pipeline," Gosgar Gosgarli, an IAE department head, told a reporter from Ekho newspaper recently. "It was their (BTC partners) concept to avoid damaging the environment and historical and cultural sites." Since then, excavation of three sites along the route has begun-a barrow field on the edge of the Zeyamchay River, a Bronze Age settlement on the shore of the Gosgarchay River, and a Middle Ages settlement near the village of Giragkasaman. Studies at a fourth site-a Bronze Age barrow near the village of Borsulu that contains ancient burial sites-are virtually complete. As this background suggests, the BTC project has the potential to uncover many new details about past generations who lived along the path of the pipeline. In the process, it may readjust local history and help to develop national identities. Creating a more prosperous future, it appears, can go hand in hand with developing a better understanding of the past. Recording the Projects For the next 30 months, a team led by Mehmet Binay, formerly a television reporter with the Turkish news channel NTV, will be producing regular video updates about the progress of the BTC project. Using local cameramen in each of the three countries, the team he leads will track the pipeline's construction and engineering achievements as well as feature its human interest, cultural, archaeological, and environmental dimensions. "It's my hope that these reports, and the final documentary which emerges, will form a bridge between the people of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey by providing a true and vivid picture of this great project and this wonderful region," says Binay. "The BTC initiative is a first of its kind in this area-a project that is breaking down barriers that are the legacy of the Cold War and building closer political, commercial and social links between three neighbouring countries." Binay began his career as a journalist in the 1990s in Germany. During the past five years, while working for NTV, he produced more than 150 weekly foreign affairs programmes, including dozens of reports about the BTC project. Binay visited Azerbaijan for the first time in 1995-one of about 20 countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia that he has traveled in while gathering material for news and geopolitical stories with a strong focus on energy. Back to Index AI 11.2 (Summer 2003) AI Home | Search | Magazine Choice | Topics | AI Store | Contact us Other Web sites created by Azerbaijan International AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com |