|

Autumn 2004 (12.3)

Pages

48-52

Pre-Soviet Era

Growing Up in Baku's Old City

by

Khadija Aghabeyli

Khadija

Kazimova Aghabeyli [1910-1989] grew up in the Ichari Shahar [pronounced

ee-char-EE sha-HAR], the Old City of Baku. Khadija was the grandmother

of medical historian Dr. Farid Alakbarov who discovered her diaries

when working on some old documents in the family's archives.

Their home was the beautiful three-storied Baroque-style mansion

that was demolished during the Soviet period in the 1970s to

make way to erect what came to be known as the Encyclopedia Building

which many people have since dubbed, "The Ugliest Building

in all of the Old City." Khadija

Kazimova Aghabeyli [1910-1989] grew up in the Ichari Shahar [pronounced

ee-char-EE sha-HAR], the Old City of Baku. Khadija was the grandmother

of medical historian Dr. Farid Alakbarov who discovered her diaries

when working on some old documents in the family's archives.

Their home was the beautiful three-storied Baroque-style mansion

that was demolished during the Soviet period in the 1970s to

make way to erect what came to be known as the Encyclopedia Building

which many people have since dubbed, "The Ugliest Building

in all of the Old City."

Khadija eventually succeeded in getting a medical degree despite

the many difficulties brought on when the Bolsheviks took control

of Baku in 1920 and her father, a businessman, could not return

to Azerbaijan from Germany where he was working.

These reflections

were penned towards the latter part of her life. As her grandson

observes: "Often the autobiography of an individual reflects

the biography of a country." Her diary covers much of the

Soviet period between 1920-1940.

We publish her reminiscences here as they provide a glimpse of

how some of the elite, wealthy members of Ichari Shahar lived

during the early part of the 20th century.

Although Khadija seemed to prefer writing Azeri in the Arabic

script which was the official alphabet until the late 1920s,

her memoirs here were penned in Russian, which by the middle

of the 20th century had become the prestigious language of Azerbaijan

as it was in other Soviet republics as well. She wanted to make

sure that her grandchildren would be able to read her memoirs

since so often grandchildren did not know the alphabet and language

of their grandparents.

During the 20th century, the alphabet had already changed three

times during her lifetime and so often the younger generations

were not able to read what their parents and grandparents had

written. Khadija did not hide her memoirs, but it would have

been dangerous to express such thoughts about the Oil Baron period

so openly during Stalin's regime and impossible to publish most

of the diary during the Soviet era.

The Ice Vendor

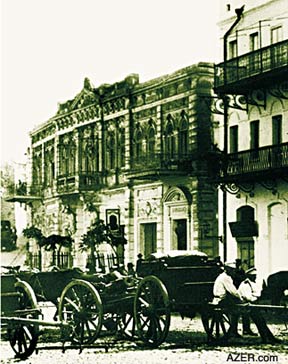

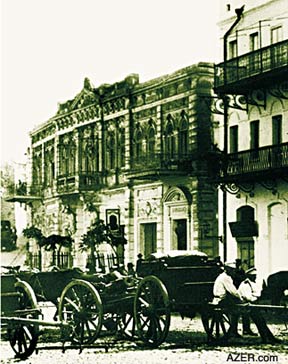

Left: This elegant Baroque style residence,

originally the "Most Beautiful Building in the Old City",

was dynamited and demolished in the 1950s during the Soviet period

only to be replaced by the Encyclopedia building or what the

residents of Baku deem, "The Ugliest Building in the Old

City". The original owner and builder was Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin

Taghiyev. Mammad Hanifa, who was living there at the time, was

the person who organized the residents of the Old City to successfully

resist the Bolshevik and Dashnak attack during the massacre of

March 1918. Note artillery on the carts in the foreground. Photo:

1918 just prior to Bolshevik attack. Courtesy: Farid Alakbarov Left: This elegant Baroque style residence,

originally the "Most Beautiful Building in the Old City",

was dynamited and demolished in the 1950s during the Soviet period

only to be replaced by the Encyclopedia building or what the

residents of Baku deem, "The Ugliest Building in the Old

City". The original owner and builder was Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin

Taghiyev. Mammad Hanifa, who was living there at the time, was

the person who organized the residents of the Old City to successfully

resist the Bolshevik and Dashnak attack during the massacre of

March 1918. Note artillery on the carts in the foreground. Photo:

1918 just prior to Bolshevik attack. Courtesy: Farid Alakbarov

I was born in 1910 in "Ichari Shahar" or the "Inner

City" which is the most ancient part of Baku. Despite the

fact that these lanes and narrow streets are relatively quiet,

we used to wake up in the mornings to hear the ice peddlers calling

out: "Ice! Ice! Buy ice at a cheap price!"

As there were no electric refrigerators in those days, people

bought ice blocks and stacked them in special wood boxes where

they kept perishable food. Instead of refrigerators, they had

to buy ice on a regular basis. Only rich people could afford

to do this, while the common people preferred to spend their

money buying small portions of meat, fish or milk on a daily

basis. Some fresh products like fresh meat coud be preserved

in refrigerators for a certain time, but such hot dishes as Bozbash

(meatball soup), Piti (lamb stew), Kabab, Dolma (stuffed grape

leaves), Jizbiz (fried liver, kidneys and other inner organs)

and Dushbara (meat dumplings) were traditionally only eaten fresh

while they were still hot.

It was against tradition to save food for the next day. For example,

I never saw my mother or my uncles or any other relatives, for

that matter, eating leftovers that had been prepared the day

before. To do so was considered a shame in our family and circle

of friends.

My grandfather

Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin was rather conservative by nature. He

didn't like tin cans or products stored in the refrigerator.

He was sure that Russians were "cold" and "frozen"

people because they ate frozen meals. For him, meat from tins

was for cats and dogs, not for human beings. My grandfather

Gatir Haji Zeynalabdin was rather conservative by nature. He

didn't like tin cans or products stored in the refrigerator.

He was sure that Russians were "cold" and "frozen"

people because they ate frozen meals. For him, meat from tins

was for cats and dogs, not for human beings.

My grandfather's house was always filled with guests. Sometimes,

hundreds of people were invited and dozens of types of dishes

were prepared. If, after completing a meal, some dishes remained

on the table and became cold, my grandfather usually ordered

them to be given to the servants. Scraps were thrown to the cats

and dogs.

No Leftovers

According to tradition in Ichari Shahar, if you invited guests

and prepared kabab for them, and if some of the best pieces of

kabab were not eaten and were left untouched, you could not store

them in the refrigerator and eat them the next day, you had to

offer them to poor people.

If you could not find any poor people, servants and beggars,

then tradition dictated that you throw the meat to the dogs.

It was not acceptible to throw any food into the garbage as it

was "Gunah"-a sin against God.

My uncle Mammad Hanifa loved to distribute cool dishes between

beggars and poor people who crowded in front of the doors of

his house. He considered offering them food to be his religious

duty.

Cold meat was only for the poor and beggars. You could insult

your guests if you offered them any food left over from the day

before even though you had stored it in the refrigerator and

carefully reheated it on the stove. This was especially true

if your guest were a high-ranking person. The guest would complain,

"I'm not a dog to eat yesterday's meal!" Then he would

leave and never return.

Camel Meat

People in Ichari Shahar loved so much to eat meat. My grandfather,

like many other people in the Inner City, preferred lamb. Veal

was rarely prepared, and pork was never eaten because we are

Muslims.

Selling camel meat in the Ichari Shahar was a traditional practice

though it happened less and less as the years went by. Sometimes,

traders would bring a camel to Ichari Shahar to sell. Usually,

it was decorated with different flowers and fabrics and looked

very beautiful. Sellers led the lone animal along the narrow

streets of the Inner City, calling out: "Hey, who will buy

my camel?"

It seemed the camels themselves were conscious that they were

about to be sold and slaughtered. They cried and you could see

tears in their eyes. It was a very strange and sad scene. In

the end, the camels were slaughtered and sold. The meat of camel

was considered a delicacy. People in Ichari Shahar loved gutabs

made of camel [camel meat wrapped and fried in a thin pastry

like a crepe]. However, in Baku camel meat was rarely eaten and,

thus, it was very expensive. Not many people could afford it.

Table Manners

Left: Khadija Aghabeyli, the author, as a

child in formal studio photo. Early 1910s. Left: Khadija Aghabeyli, the author, as a

child in formal studio photo. Early 1910s.

Our parents used to carefully instruct us about table manners

and how to be very appropriate when we ate. We adopted both the

Eastern and European ways of eating. Bozbash [meatball soup]

was eaten with spoons, although pilaf [plov] and stuffed grape

leaves [dolma] were eaten with fingers. My grandfather was so

skillful in being able to pick up the grains of rice of the pilaf

with his three fingers without dropping a single grain.

My father and uncles ate their pilaf with spoons, following the

European traditions. According to traditions in the Inner City,

our parents made us refrain from eating too much or too fast

or from reaching across the table for any of the dishes. It was

also forbidden to take the last piece or portion of anything

from any of the main dishes.

If one of us kids broke any of these rules, our parents would

reprimand us: "Are you a Gormamish?" (meaning "someone

who has never seen such a thing in his life"). It was the

most offensive expression that they ever used with us.

Another expression that they used was "Pinti" [sloppy

person]. Once when my little brother Haji-Agha took a piece of

meat from the Bozbash and clumsily spilled some soup on his suit,

my mother hit him on the head and rebuked him angrily: "We

give you the best things, but you still remain 'Gormamish' and

'Pinti'-like a son of a barefooted person from the Outer City.

Get up and leave the table!"

Despite how wealthy our family was, we were brought up with strict

discipline and rather Spartan conditions. The first half of the

day we spent at school where we were obliged to wear a special

uniform just as soldiers do. During the second half of the day,

we did our homework and helped with routine tasks at home or

helped to look after house.

It was considered that a good wife should know everything about

housekeeping: she should be able to sew, weave carpets, cook

food and clean house. In addition, we had teachers for music

(piano) and other tutors, who came to our home to instruct us.

Sometimes, we went to visit friends or to the theater, usually

accompanied by our parents. Normally, they did not allow us to

walk in streets alone. They didn't give us very much pocket money

and we had no right to say anything against the will of our parents.

My father Alakbar Kazimov worked in Mainz (Germany). He was a

businessman and had a factory there. He wanted to take my mother

Sariyya there, too, but she didn't want to go. "I can't

go without my parents," she complained. "I can't leave

the Inner City where I grew up." So father lived and worked

in Mainz all by himself; but prior to the time when the Bolsheviks

took control of Baku [1920], he often returned to see mother

and me.

Grandfather

Above: Examples of European

attire worn by wealthy Azerbaijani women during the Oil

Baron era (1885-1920) prior to the Bolshevik invasion in Baku

in 1920. Ana Khanim Taghiyeva in 1932, daughter of Mammad Hanifa

Taghiyev (Khalida's cousin). Umleyla Ibrahimbeyova (Khadija's

aunt) in 1908.

My grandfather (mother's father), who died at quite an old age

in 1914, was a very famous person in Ichari Shahar. He had been

named after the millionaire and philanthropist Haji Zeynalabdin

Taghiyev (1823-1924) [who, to this day is respected as having

been the most philanthropic of all the Oil Barons]. My grandfather

constructed many buildings in Ichari Shahar. In 1873 he built

the gates in the fortress walls [adjacent to Sabir Garden]. He

was known as a very smart person; people had nicknamed him "Gatir"

Haji Zeynalabdin ["Gatir" means "mule", but

connotes cleverness.]

My grandfather owned many shops and stores in Baku and had some

land in Gala village. He had two large homes in Ichari Shahar-one

nearby the "Chain House" in the Inner City [where the

Encyclopedia Building now stands] and the other in modern Aziz

Aliyev Street [where the Yin-Yang Restaurant stands not far from

the Azerbaijan Cinema and Natavan statue]. Her grandfather's

house was constructed at a place where the fortress wall separated

the Inner City from the Outer City. The front of the house opened

to the Outer City, while the courtyard was located in the Inner

City.

An underground tunnel connected these two homes to each other.

When I was a child, I often walked along this way from one house

to the other with my mother. We even had electricity and lamps

along this underground path even though electricity was very

rare and expensive back in those days around 1912.

Left: Typical veiling of Azerbaijani Muslim

women prior to the Bolshevik Revolution. Left: Typical veiling of Azerbaijani Muslim

women prior to the Bolshevik Revolution.

My grandfather

was a traditionalist. He was convinced that Azerbaijanis must

only dress in the national costume. He hated European clothes.

He used to trim his beard and large moustache with meticulous

care, and he always wore the Azerbaijani national dress including

the "papag" [pointed hat]. The expensive highly decorative

dagger that he wore in his belt, which was made of silver and

gold, was also part of his national costume. Even when his sons

and daughters begged him to wear a black European suit to attend

the theater or other official venues, grandfather refused. And

with such a vengeance!

He was a very stubborn man, but people loved him anyway because

he organized charity feasts during the Muslim holidays. During

those days, the doors of his Baroque-style mansion in the Ichari

Shahar were always open. Anyone from the street could enter and

sit at a very long table and eat as much as he wanted. Dishes

were brought in and refilled by servants all day long. It wasn't

only my grandfather who made these feasts; many people in Ichari

Shahar organized such charity tables for the poor.

My grandfather liked horses and horseracing. He had a lot of

horses in his villa in Mardakan near Baku [a summer resort for

the wealthy on the Absheron Peninsula, not far from the sea].

He used to buy expensive Arabian horses and feed them French

chocolate. Once, a veterinarian told him that chocolate was bad

for their teeth, and so he stopped doing that and substituted

straw for the chocolate.

Father

In contrast to my grandfather, my father Alakbar was a modern

man. He graduated from Commercial College in Baku and was quite

educated. He knew several foreign languages including English,

German and French. His own father was a wealthy merchant from

"Bayir Shahar" (Outer City) and owned a number of carpet

shops on Aziz Aliyev Street, directly opposite the mansion belonging

to my grandfather.

Both of my grandfathers were friends, so it was not unusual at

all that their children-Alakbar and Sariyya-would end up marrying

each other. My father's family presented a dowry consisting of

a large gold plate filled with diamonds. Afterwards, my father

left for Germany on a long business trip. He established a factory

that produced Caucasian carpets in Mainz. He was very successful

in selling them to European markets, and they brought substantial

profit for our family. Unfortunately, my father antagonized my

mother's brother-Gochu Mammad Hanifa Taghiyev.

Gochu Mammad Hanifa

Uncle

Mammad Hanifa was a very famous person in the Inner City because

he had done the most to save Ichari Shahar from the Armenian

pogroms in 1918. Uncle had organized the armed resistance of

the local residents in the Inner City. Uncle

Mammad Hanifa was a very famous person in the Inner City because

he had done the most to save Ichari Shahar from the Armenian

pogroms in 1918. Uncle had organized the armed resistance of

the local residents in the Inner City.

Left: Mammad Hanifa Taghiyev

and his two children.Hanifa organized the residents of the Old

City to resist the Bolsheviks and Dashnaks massacre in 1918.

Many credit their lives to him. When Bolsheviks gained control

of Baku in 1920, they executed Hanifa.

People in Ichari Shahar still remember his name with deepest

respect and awe and say, "We're alive today only because

of Mammad Hanifa's efforts".

But Mammad Hanifa had a difficult character and, thus, he created

many enemies for himself. He wanted all the people in Ichari

Shahar to accept his leadership. My father often disagreed with

him. In contrast to my uncle, my father was very patient, well

brought up, calm, and even somewhat melancholic as a person.

My father's cool dignity used to enrage Mammad Hanifa. Once,

he shouted at my father: "I'll kill you!" Then father

took his revolver out of his pocket, offered it to Mammad Hanifa

and calmly said: "Take it and kill me if you dare!"

Uncle Hanifa stared at my father in rage, turned and stomped

out of the room.

In 1914, World War I broke out. Shortly afterwards, grandfather

Haji Zeynalabdin died. His great wealth was divided among his

children. The greatest portion of the wealth, including the steamship

company Volcano, became the property of Uncle Mammad Hanifa.

At first, Mammad Hanifa managed this business very well and even

developed the business by purchasing new German ships like the

Bremen Volcano. But then the business started to fail; he had

to sell a considerable part of grandfather's property, including

some of his mansions in the Inner City as well as some of his

villas.

About that time, Mammad Hanifa met a lovely Georgian woman and

moved in with her in a separate house, even though he had both

a Muslim wife and children in another house. It was a tradition

in those days for wealthy men in the Inner City to have two families-one

family with an Azerbaijani woman, which was his official family

and another wife, who was Russian or Georgian, in an unofficial

relationship.

During this period, my father continued to work in Germany, which

at that time happened to be at war with Russia. As Azerbaijan

was part of the Russian Empire, all routes between Germany and

Azerbaijan were severed. Father often wrote letters to my mother

and she would write him back. However, many of our relatives,

including my mother's brothers hated my father and used to tear

up his letters and trash them.

Under pressure, my mother was forced to divorce my father. In

1916, she remarried with her cousin Alizade, and I had to leave

my father's home and live with my aunt or, sometimes, with my

uncle for a certain period of time. Then mother took me back

home with her again.

When I was six years old, mother sent me to St. Nina's Russian

School for Girls, which was located on Nikolai Street [now Public

Schools No. 132 and 134 on Istiglaliyyat Street across from Baku's

City Hall]. We studied various subjects including foreign languages.

I became fluent in Russian and French.

Later, I went to Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev's Boarding School

for Muslim Girls, which during the Soviet times became known

as the 16th Soviet School named after the writer Husein Javid.

Both of these schools were famous. Daughters of many famous people

from Ichari Shahar and Bayir Shahar studied there. Many of them

were my friends such as Govhar Safaralizade (Safaraliyeva), Khadija

Kalantarli, Giz-Ana Rustamzade (Rustamova), Sara Akhundzade (Akhundova),

Sakina Akhundzade (Akhundova), Nughra Jafarzade (Jafarova) and

others.

In school, not only did girls study various sciences and languages,

but they also learned the art of housekeeping, sewing and drawing.

In 1921, I created an album where my classmates drew various

images, flowers and animals with watercolors and wrote poems

and verses devoted to me.

Left: The author: Khalida Aghabeyli with her

husband Aghakhan Aghabeyli in 1934. Left: The author: Khalida Aghabeyli with her

husband Aghakhan Aghabeyli in 1934.

I had

a very close schoolmate-Sara. We became friends when I was 9

years old (1919). Later, our parents became friends, too. Sara

had a cousin, a boy who studied and worked in Baku, who often

visited her. Once, we met at a Charity Evening organized by the

Oil Baron Haji Zeynalabdin Taghiyev to which our parents had

been invited. Later, this boy often visited us in our home together

with Sara.

He accompanied us when we went out for walks or were invited

by our friends and relatives. His name was Aghakhan. He was six

years older than me. It turned out that he had fallen in love

with me. However, he did not tell me anything about his feelings.

He was thinking: "Let her grow up; then I'll marry her"

(at least, that's what he told me years later when we married).

As you can guess, he became my future husband. When I was 15

years old, I also became very fond of him. I once sent him a

letter telling him that I loved him, too, but he didn't answer

me. Then, he disappeared for many years. We met again only in

the 1930s when we got married.

Bolsheviks in Baku

The Bolsheviks captured Azerbaijan in 1920. That's when they

came to our home in the Inner City and confiscated our furniture

and valuable things. They arrested and shot my mother's brother-Gochu

Mammad Hanifa Taghiyev because he was an Azerbaijani patriot

and had headed up the resistance against the Armenians [and Bolsheviks]

in 1918. We were barely able to escape only because my father's

brother Aghahusein Kazimov was a high-ranking Bolshevik and he

protected us. He was the Commissar (minister) of Health Care

in the Bolshevik government of Azerbaijan.

We were not arrested [unlike so many other wealthy people who

were imprisoned or executed] but our life became miserably poor.

My mother's attitude towards me got worse. She wanted me to find

a job at such an early age, and I was forced to work in a factory

that Mashadi Rustam owned. This factory continued to operate

even during the first years of the Bolshevik Revolution because

Communists declared New Economic Policy (NEP) allowing restricted

private business activities in Baku.

My father Alakbar wanted to help me, but it wasn't so easy. He

was not able to return to Baku legally as he was considered a

capitalist. The Bolsheviks would have immediately arrested and

shot him. Besides, his brother Aghahusein who still remained

in Baku was a commissar and he would have been discharged from

his post, arrested or exiled if Bolsheviks became suspicious

that he had "a brother who was a Capitalist".

Nevertheless, my father realized how hard my situation was and

sent me a letter from Germany. One of his relatives delivered

it to me. His note mentioned that on a certain date he would

secretly arrive on the shore near the Boulevard in a little motorboat

and would wait for me. I was to come and take a seat in this

boat and escape from Baku together with my father. He wrote me

that he already bought a house in the Anzali [Enzeli] in Iran,

where I would stay for a year studying German language under

the supervision of teachers. Later, he would take me to Germany.

At the appointed time, I gathered some essential private things

in a sack with the intention of walking down to the sea. But,

alas! My mother somehow figured out my plans and locked me in

the house. I beat on the door with all my strength and cried

out, but she would not open the door. My father waited for me

for a long time and then he left. He never tried to return to

Baku again. So, I remained here forever. My life would have been

so different if I had met my father that day.

Mother continued to tell me that I was old enough to earn money.

At first, I went to work in the factory of Mashadi Rustam, the

husband of my mother's sister. Then, in 1913, when I was only

13 years old, Mashadi Rustam took me to my uncle, the Health

Care Commissar and pleaded: "Give her a job. Let the girl

work. It would be so beneficial for her."

However, such

activities were not welcomed in the Soviet government when a

high-ranking person hired close relatives for his office. Therefore,

my uncle sent me to Commissar Samad Aghamalioghlu on the second

floor of the Government House and asked him to help me.

Aghamalioghlu said: "Sit down, my daughter and learn to

type. You will become a good typist in the future." And

so I typed texts all day long after returning from school, and

he gave me a monthly salary. That's how I came to work at the

Ministry of Agriculture.

Thus, I worked and, at the same time, studied at the 16th Soviet

School named after Husein Javid. I graduated in 1926 at age 16.

I wanted to become a physician. Therefore, I enrolled in the

Medical Faculty of Azerbaijan State University. I attended evening

classes at the university and worked as a typist during the day.

This continued for the four years of my university studies. Beginning

in the fifth year, I received a student stipend of 90 rubles

per month and, thus, was able to stop working. In 1930-31, I

graduated from the Curative Prophylactic Department of the University

and started to work as a physician. My first assignment was a

clinic of workers in the Gala district of Baku.

Dr. Khadija

Kazimova Aghabeyli worked there as a doctor in Gala from 1931-1934.

From 1939-1945, she was the head physician of the Children's

and Women's Consultation Clinic in Ganja, in north central Azerbaijan.

Later she was appointed Director of Ganja's Central Children's

Hospital. She gained such a reputation among families that they

called her, "The God of the Children".

During World War II (1941-1945), Khadija organized and supervised

the treatment of many wounded Azerbaijani soldiers and was awarded

the medals: "For Defense of the Caucasus" and "For

Victory Over Germany". She also received the medal, "Excellent

Health Care Worker". Her husband Professor Aghakhan Aghabeyli

(1904-1980) became a distinguished specialist in genetics and

developed two new buffalo cattle breeds-the Caucasian Buffalo

and the Azerbaijan Buffalo.

They had three children-Rena who has a Doctorate in Biological

Sciences and who is a specialist in Molecular Biology and Antioxidants;

Tahir who has Candidate Degree (First Level Doctorate) in Technical

Sciences and who is the inventor of agricultural equipment; Tagor

(died in 2002) who was an Engineer. During the Soviet period,

he was the Director of the Transcaucasian All-Union Institute

Of Tractors.

From Azerbaijan

International

(12.3) Autumn 2004.

© Azerbaijan International 2004. All rights reserved.

Back to Index AI 12.3 (Autumn

2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|