|

Autumn 2004 (12.3)

Pages

62-69

Mugham Jazz: Vagif Mustafazade

Musical

Roots in Baku's Old City

by Betty Blair

All photos courtesy

of:

Vagif Mustafazade Humanitarian Fund / Afag Aliyeva

Pianist

and composer Vagif Mustafazade (1940-1979) was the creator of

the jazz mugham movement in Azerbaijan in the 1960s. By merging

two musical genres - Western jazz and Eastern mugham, a type

of traditional improvisational modal music - he created "mugham

jazz", a new sound that was uniquely Azerbaijani. Familiar

Eastern melodies found new expression in Mustafazade's free-spirited

piano stylistics. Pianist

and composer Vagif Mustafazade (1940-1979) was the creator of

the jazz mugham movement in Azerbaijan in the 1960s. By merging

two musical genres - Western jazz and Eastern mugham, a type

of traditional improvisational modal music - he created "mugham

jazz", a new sound that was uniquely Azerbaijani. Familiar

Eastern melodies found new expression in Mustafazade's free-spirited

piano stylistics.

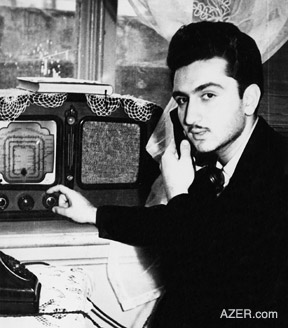

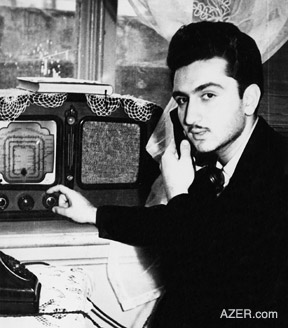

At the end of World War II when Vagif was growing up, jazz had

been banned in the Soviet Union. Stalin had labeled it the "music

of the capitalists". But jazz fans and musicians like Vagif

used to listen secretly on short wave radios so they could know

the latest jazz renditions on BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation)

and VOA (Voice of America).

Despite the Soviet system's antipathy toward jazz, Mustafazade

was able to achieve international recognition for his music even

during his lifetime. In 1978, he won First Prize at the Eighth

International Jazz Festival in Monaco for his composition "Waiting

for Aziza". In 1979, he was named People's Artist of Azerbaijan.

That same year, he suddenly collapsed and died while performing

onstage in Uzbekistan. He was only 39 years old. His legacy as

a pioneer of jazz mugham preceded his own time and still strongly

impacts how jazz is performed in Azerbaijan today.

Covers of the 6 CDs - Vagif Mustafazade Jazz Collection. Order

at:

AI

Store

Search for "Jazz".

Now that Azerbaijan has gained its independence from the Soviet

Union (1991), Mustafazade's brilliant jazz renditions finally

have a chance to become known beyond his native land and the

former Soviet Union. A collection of 6 CDs featuring 80 of his

works - many of them originally produced on vinyl LPs released

during Vagif's lifetime; others are rare, unreleased selections

from the 1960s and 1970s recorded at Baku's Radio and Television

Studios or preserved at Azerbaijan's National Voice Recording

Archives. The idea for the project came from Mike Barnes, President

of UNOCAL Khazar Ltd., which sponsored the project. Pirouz Khanlou,

Publisher of Azerbaijan International produced the 6 CD set.

Javanshir Guliyev was Project Director and did the digital restoration.

Tarlan Gorchu and Ilham T. Aliyev of Tutu Publishing were involved

with the design of the 6 CD Vagif Mustafazade Collection.

Afag Aliyev of the Vagif Mustafazade Humanitarian Fund provided

photos. Alla Bayramova, Director of the State Museum of Azerbaijani

Musical Culture, also assisted with photos.

Betty Blair,

Editor of Azerbaijan International, wrote the biographical article

after interviewing Vagif's contemporaries who include:

1. Poet Vagif Samadoghlu: close friend of Mustafazade and pianist

from youth. Vagif has since been honored as "National Poet

of Azerbaijan". He is the son of the famous poet Samad Vurghun,

Member of Parliament and currently one of Azerbaijan's six Parliament

representatives to the Council of Europe.

2. Rafig Guliyev: classical pianist and "People's Artist

of Azerbaijan", Professor at Baku's most prestigious music

institution, Academy of Music.

3. Javanshir Guliyev: composer who knew Vagif from working at

Azerbaijan's State Television and Radio Company.

4. Vasif Babayev: childhood friend who grew up together with

Vagif in the Old City.

5. Eybat Mammadbeyli: guitarist who performed with Vagif's vocal

group "Sevil" in the 1970s.

Arzu Aghayeva, Ulviyya Mammadova, Aynura Huseinova, Gulnar Aydamirova

and Jala Garibova were involved in the Azeri translation for

this CD project which is available at AZER.com - Store.

Biography - Vagif

Mustafazade

Be

prepared for a barrage of superlatives if you ask jazz musicians

and jazz lovers in Azerbaijan about Vagif Mustafazade (pronounced

vah-GIF mu-stah-fah-zah-DEH) (1940-1979). Be

prepared for a barrage of superlatives if you ask jazz musicians

and jazz lovers in Azerbaijan about Vagif Mustafazade (pronounced

vah-GIF mu-stah-fah-zah-DEH) (1940-1979).

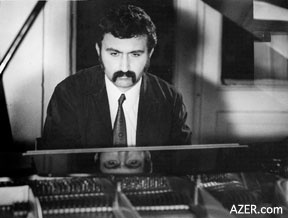

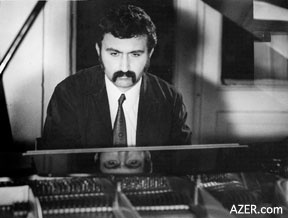

Left: Vagif Mustagazade,

creator of

"mugham jazz" (1940-1979)

Rafig Guliyev, one of Azerbaijan's most famous classical pianists

and one of Vagif's contemporaries, reflects on those days: "Vagif

burst in on the jazz elite like a bright meteor.

He was a pianist of great talent and brilliant dimensions. There

has never been another pianist from Azerbaijan of such scale,

of such hurricane strength and talent. He made an invaluable

contribution to jazz. He was first when it came to fusing Azerbaijan's

traditional mugham with jazz, and as we say, 'First is always

first!'"

Rafig recalls Vagif's live performances: "Hearing Vagif's

recordings is nothing when compared to seeing him perform live.

It was something indescribable. Even the video footage that exists

today doesn't do justice to his brilliance. It doesn't express

the feelings and impression of his live performances. How can

I describe it? You had to have seen it. It was more than passion.

Vagif was so intense when he played: you could have killed him

and he wouldn't have even felt it."

Today Vagif is most remembered, not for being a jazz pianist

in the classical sense of the word, but for taking traditional

Azerbaijani elements - modal scales from Azerbaijan's own improvisational

mugham music-and blending them with jazz to create his own signature.

This style is sometimes referred to as "mugham jazz".

It was a unique fusion of music of both East and West.

Though the West didn't know Vagif very well, there were a few

outstanding jazz performers and critics who had heard his works.

One was Willis Connover, who directed Jazz Hour on Voice of America

(VOA) and who saw Vagif perform at the 1967 Tallinn Jazz Festival

in Estonia. Connover called Vagif "the most lyrical musician

I have ever heard".

"Dizzy" Gillespie, one of the greatest trumpeters and

bandleaders in jazz history on the American scene, heard Vagif's

works and remarked: "Vagif was a genius but it seems that

he was born before his time. He brought us the music of the future."

By any standard, Vagif as jazz pianist-composer had chalked up

some impressive prizes in his short lifetime despite the fact

that he had grown up in a period "when Azerbaijan did not

wear the smile of jazz on its face," as his contemporary,

poet Vagif Samadoghlu, described the ban on this genre during

the 1950s and 1960s in the Soviet Union.

Awards Awards

In 1978, Vagif Mustafazade won the coveted Grand Prize at the

8th International Monte Carlo Jazz Competition in Monaco.

Left: Vagif

Mustafazade won the Monte Carlo Jazz Competition Festival in

1978 for his work, "Waiting for Aziza".

Musicians

from numerous countries had submitted their written compositions.

The judges listened, not knowing the name of the work, its composer,

or which country it represented. Voting was by secret ballot.

Vagif chose "Waiting for Aziza" which he had written

in anticipation of the birth of his second daughter, born in

1969. No one expected an unknown musician from Azerbaijan to

take the First Prize.

Vagif was extremely proud of the honor and in a radio interview

a few months before his death in 1979, he commented that winning

the Monte Carlo Jazz Festival had given him such confidence that

he had since doubled his intensity and enthusiasm.

At the International

Jazz Festivals in Tallinn (Estonia) in 1966 and 1967, Vagif took

First Prize both years. He also won the Tbilisi International

Jazz Festival (1975) and was named the Best Pianist of Tbilisi

78. He also played in Kyiv, Ukraine (1977) and was a three-time

winner of jazz festivals in Baku. In 1979, he performed at the

All Union Composers' Concert Hall in Moscow, along with some

of the other well-known Soviet jazz musicians.

The hall was packed. Vagif received a standing ovation. Already

by 1979, he had produced six LPs, or "vinyls" as they

were called, with Melodiya, the single record producer in the

Soviet Union. This was a feat in itself, given the government's

enormous overburdened bureaucratic system.

In Azerbaijan, he eventually was recognized with the highest

honor possible - National Artist of Azerbaijan (1978). In 1982,

he was awarded the State Prize of Azerbaijan posthumously.

Jazz Roots in Baku Jazz Roots in Baku

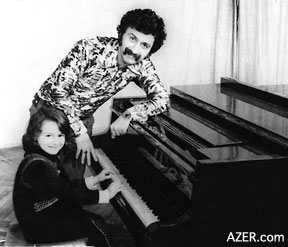

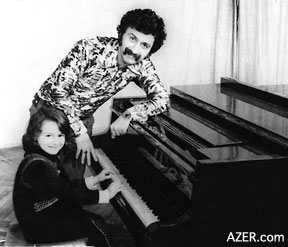

Left: Vagif with his daughter

Aziza in the late 1970s.

Jazz

had deep roots in Baku long before Vagif Mustafazade arrived

on the scene. In the late 1800s, Baku was already known for its

oil and Europeans were gravitating to this city on the western

shores of the Caspian. Together with local entrepreneurs, they

succeeded in producing more than half of the world's supply of

oil in those years.

At about the same time, America was giving birth to a new musical

form - jazz. These mesmerizing melodies and rhythms emanated

from the restaurants and back alleys of cities like New Orleans

and Chicago.

This new musical sound was a synthesis of various cultural traditions,

drawing upon African rhythms, the Asian love for improvisation

and abstract thinking, and European classical music.

Soon afterwards,

this new musical synthesis found its way to other cities in the

world, even to Baku, which because of its oil wealth was not

nearly as isolated in 1900 as it would become during the Soviet

period (1920-1991). Newspaper archives in Baku indicate that

bands were performing jazz in restaurants at that time. There's

even a strong likelihood that the Nobel Brothers - Robert and

Ludwig - who were deeply involved with Baku's oil development

might have listened to jazz, though there are no early recordings

to confirm what the professional quality might have been.

By a tragic twist of fate, the economic oil boom, fueled by its

vigorous entrepreneurial spirit, came to an abrupt halt when

the Bolsheviks took control of Baku in 1920. The Soviet regime

established their authority in the region, and soon Soviet doctrine

penetrated all aspects of life - even attitudes toward art, literature

and emotions. Everything became subject to Communist ideology

and central control. Nothing escaped its scrutiny, not even music,

including what to sing, what to perform and what to listen to.

Major decisions and ideological direction were determined in

the Kremlin in Moscow - not by local artists.

In Soviet Azerbaijan in the late 1930s, the State Jazz Orchestra

was organized by composer and pianist Tofig Guliyev and Maestro

Niyazi. Their ensemble consisted of five saxophones, three trumpets,

a trombone, piano, guitar and various percussion instruments.

The musicians played classical jazz, but they also improvised

on some of the traditional folk songs and mughamstraditional

Azerbaijani modal music.

Enter Vagif Mustafazade. Vagif was born in Baku, Azerbaijan,

on March 16, 1940. World War II was already underway: the Soviet

Union would send troops to fight against Hitler the following

year. Although Azerbaijan never became a combat zone, the Republic

suffered tremendous casualties, as did the entire Soviet Union.

In Azerbaijan alone, of the 700,000 Azerbaijanis who were recruited

for war, an estimated 400,000 never returned. Afterwards, the

Cold War would dog relations between the Soviet Union and the

West and would impact Vagif for the rest of his life, especially

in terms of his ability to become known as a jazz pianist and

composer beyond the territory that the West called "The

Iron Curtain".

Jazz Banned

After World War II ended in 1945, Stalin (1879-1953) as the Supreme

leader of the Soviet Union imposed a prohibition against jazz,

as "music of the capitalists". There wasn't a decree,

per say, that singled out jazz; rather there was a decision by

the Party "Against Formalism in Literary Art". This

included jazz and every other art form that was created and influenced

by the West. These prohibitions were established, despite the

fact that the U.S. and the Soviet Union had fought as allies

against the Germans. Hitler, who always touted the superiority

of the Arian race, had already banned jazz in Germany in 1933

as "inferior music" because this was music of Negroes,

which he deemed to be a lesser race.

According to Azerbaijani composer Javanshir Guliyev, during the

Soviet era, the music that was most esteemed by the highest echelons

of power was what one might call "Monumental Music",

which meant classical music - symphonies, concertos, operas and

ballets. "This was their attempt to express their quest

for the greatness and monumentalism of the State - in this case,

the Soviet Empire." Javanshir feels that this Soviet trend

somehow was influenced by Hitler's fondness of the music by Wagner

with its majestic sound and large orchestras. The Communists

simply emulated Hitler's tastes, Javanshir believes.

Consequently,

between 1945 and Stalin's death (1953), not only was jazz prohibited,

but so were the instruments closely associated with this genre.

Even the saxophone solo in Ravel's famous "Bolero"

was substituted with a bassoon. Jazz performances in the Soviet

Union were entirely banned during these years.

Such restrictions could have been anticipated, given the nature

of jazz itself. Classical pianist Rafig Guliyev describes it

this way: "What is jazz other than freedom, independence

and improvisation? Any kind of freedom or any kind of improvisation

goes beyond the borders of what the Bolsheviks could control.

It's not that they didn't like jazz or didn't understand it.

Simply, they were afraid of it. Jazz is the most progressive

music on earth!" Rafig observes that, in general, totalitarian

regimes are invariably suspicious of artistic forms that are

based on independent, spontaneous and improvisational techniques,

especially at a grass roots level.

My Mom, the Sea, and the Old City My Mom, the Sea, and the Old City

What influenced Vagif to become such a great musician? According

to Rauf Farhadov, Vagif offered a simple explanation, which is

both poetic and profound in its implications.

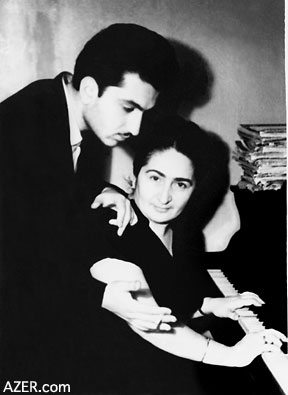

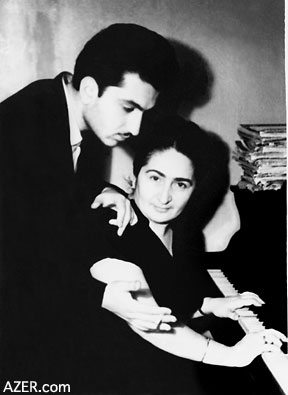

Left: Vagif with his mother

Zivar Khanim (1960s).

He credited his music to three things: "My mom, the sea,

and 'Ichari Shahar'". In other words: Zivar Aliyeva, the

Caspian, and Baku's oldest residential section where Vagif grew

up. He saw these three factors playing the greatest roles in

shaping his character and in providing him with tremendous tenacity,

identity, and vision to cope with the unreasonable authoritarianism

that surrounded him.

Home for Vagif was Baku's "Ichari Shahar" (literally

"Inner City", which often is referred to as "The

Old City" by foreigners). No one is quite sure how early

to date this section of town, surrounded by high citadel walls

- perhaps, to the 12th century. Perhaps earlier.

Not only was "Ichari Shahar" with its narrow winding

streets, the oldest, most picturesque part of the city. Not only

was it adjacent to the sea, but it boasted one of the most closely

knit neighborhoods which had the greatest concentration of Azerbaijanis.

Though many Russians, Armenians, Jews and even some Georgians

and Lesgians lived in other sections of the capital, the Old

City was still populated mostly by Azerbaijanis, who were identified

by their accent, food and character.

"Ichari Shahar", says Rafig Guliyev, "was the

'belly-button of Baku'. Kids who grew up there walked with their

own swagger. They were difficult kids. To tell you the truth,

us city guys were a little afraid of the Inner City guys. They

were known for their stubbornness, their belligerence, their

determination," Rafig recalls. "They had an acute sense

of justice. It was like 'all for one and one for all'. And they

were always 'the life of the party' - the center of attraction

- passionate and free-spirited. They had a sense of identity:

you could even identify Inner City guys by the clothes they wore

- loose pants and white shirts."

Childhood playmate Vasif Babayev (now a TV producer) recalls

those early years growing up together with Vagif in "Ichari

Shahar". "Those years you could hear mugham music coming

out of nearly every home. When you passed by under the windows

along those narrow streets, you could hear people playing the

tar and kamancha (traditional stringed instruments). 'Ichari

Shahar' was a unique place from this point of view. Vagif grew

up literally surrounded by mugham."

There was another thing about the Inner City: traditionally everybody

who lived there was given a nickname. Vasif remembers: "Vagif's

nickname was 'muzikant' ('musician' in Russian) because he had

the best sense of rhythm and music. We used to gather in the

park below Philharmonic Hall where public dances were held -

ballroom dances in the open air. Vagif was nine or ten years

old at the time. He was the best dancer! And he was good looking.

Everybody loved him - guys and girls alike. Everybody wanted

to attract his attention."

The boys from "Ichari Shahar" played together. Vasif

describes some of their favorite haunts: the small beach (which

no longer exists) in front of Giz Galasi (Maiden's Tower), and

the park below the Philharmonic with its iron bars through which

they would wiggle after 7 p.m. when the park closed so they could

play soccer or swim in Baku's deepest pool (4 meters). "We

used to climb up on the frog statues and jump into the water,"

Vasif recalls. "And when it came to that mysterious famous

landmark, the Maiden's Tower, we used to try to find a way to

go up inside it. At that time, only scholars were allowed inside.

We would beg them to take us up so we could climb the circular

stairs and exit on the roof that opened up to a view of the whole

city."

The Caspian Sea is inextricably linked with the Old City and

Vagif could see it from his window just a few blocks away when

he practiced the piano. No doubt, the rhythm of the waves, characterized

by improvisation and variability shaped his music as well. But

it's likely when Vagif mentions the sea as one of the primary

factors shaping his music that he also means his yearning for

freedom and faraway places. It wasn't just poets who stood at

the edge of the Caspian imagining distant shores and life beyond

the restrictive Soviet rule. This may have been the Caspian's

most compelling feature for Vagif. It was one of his greatest

dreams to be able to perform outside the borders of the Soviet

Union. Unfortunately, it was a dream that never became reality

for him.

And then there was his mom - Zivar Khanim (Mrs. Zivar) - as she

was endearingly and respectfully called. Vagif lived with his

mom on the third floor of what had once been a residence built

during the Oil Baron era on the eve of the 20th century. Like

hundreds of other buildings in the center of Baku, the Soviets

had confiscated the property and furniture of the wealthy and

elite, and divided these luxurious residences into numerous apartments.

That one-room apartment became the repository of an immense musical

knowledge that would shape the movement of jazz in Azerbaijan.

Vagif's father, Aziz Abdul Karim oglu Mustafazade, a major in

the Medical Service, served eight years in the Far East. He was

known to have played the tar, a traditional stringed instrument,

quite well. The tar is one of the primary instruments traditionally

used in performing mugham music. Little is said about Vagif's

father. Vagif's contemporaries today only mention the powerful

influence of his mom.

Zivar Khanim taught piano at School No. 1, a seven-year (elementary)

music school. These days in Azerbaijan, it is not unusual for

a young girl to pursue a music career but in Zivar Khanim's day,

it was quite an achievement. She should be given immense credit

for becoming a professional musician in the 1920s and 1930s.

It wasn't so easy for women to enter professional music at that

time. Despite the fact that the Bolsheviks had established a

new government in 1920 that would lead to the formation of the

Soviet state, Azerbaijan at that time was still basically a traditional

Muslim society that censured women who dared to move outside

the arena of the home, and pursue careers, especially those which

required any performance in public.

For example, it was 1912 before the first woman ever performed

on stage in Azerbaijan. Shovkat Mammadova had just returned from

Milan after professionally studying voice there. Up until then,

it was men who had always performed women's roles in operas.

But Shovkat, who was 15 at the time, appeared on stage in Baku

in European dress without wearing the traditional veil. It was

a disaster. Too much, too soon. She was threatened and run off

stage. Had she not run out the back door and jumped into a carriage,

waiting for her in anticipation of such an emergency, the story

might have ended differently. The driver was instructed to "speed

away so that the sparks would fly from the horses' hooves".

For the next several days, it is said that Shovkat hid in oil

fields on the Absheron peninsula. Shaken, when she finally managed

to return to the city a few days later, she decided to leave

for Tbilisi (Georgia) where attitudes towards women performing

on stage were more tolerant. She would not return to Baku until

eight years later at which time she was able to pursue a musical

career as a professor in the Music Conservatory. It wasn't until

the late 1920s that the Soviets began to succeed in their campaign

of getting Muslim women to shed their veils.

Hajibeyov

It was Uzeyir Hajibeyov (1885-1948), who had arranged for Shovkat

to perform on stage that ill-fated evening. He did not give up

in his determination for women to excel in music and to comprise

much of the pedagogical powerhouse for training youth in music.

Hajibeyov would become Zivar Khanim's mentor and teacher.

Hajibeyov became known as "The Father of Composed Music

in Azerbaijan" because he challenged musicians to write

down Azerbaijan's traditional music. Prior to that time, all

music had been played by ear and based entirely upon improvisation.

In 1945 Hajibeyov published his major work, "Principles

of the Folk Music of Azerbaijan" (The English edition came

out in 1985). It was a topic he spent nearly 20 years to research.

He identified seven main modes [mughams] built on 12-tone scales,

which, according to him, provided 84 variations upon which to

improvise melodies. Zivar Khanim would pass this knowledge and

passion for mugham music on to her son.

Vagif's friends say that mughams based on the modal scales of

"Bayati Shiraz" and "Shur" became his favorites.

"Shur" was one of the most popular mughams since a

great majority of Azerbaijan songs and folk dances were based

on this mode. Some may wish to differ with the analysis, but

Hajibeyov describes "Shur" as "cheerful and lyrical"

while he considered "Bayati-Shiraz" as "melancholic

and sad".

But not only did Vagif's knowledge of folk music shape the music

he would create, it affected his attitude toward traditional

folk musicians. "Unlike many other jazz and classical musicians,

Vagif never looked down on folk musicians," according to

Javanshir. "He got on well with the mugham singers and tar

players. He understood their language and they understood his.

Other jazz musicians snubbed folk musicians and looked upon them

condescendingly, but Vagif took folk music and folk musicians

very seriously."

Early Beginnings

Left: By age nine, Vagif

was playing Left: By age nine, Vagif

was playing

Gershwin's jazz rendition of "The Man I Love". His

mother, Zivar Khanim was his first piano teacher.

Vagif started playing the piano at age three. That was the same

year that Zivar Khanim began to realize that her son had an exceptional

memory. Poet Vagif Samadoghlu recalls the story that Zivar Khanim

told his father, the famous poet Vurghun. "Once Zivar Khanim

was quoting some lines from my father's play, 'Farhad and Shirin'.

Vagif heard her. Though he was little more than a toddler and

too young to comprehend the meaning of the drama, he started

repeating the lines back to her. Zivar Khanim was amazed. And

so was my father," recalled Vagif the poet.

Vasif Babayev, Vagif's childhood friend, remembers how everybody

was afraid and paid attention to Zivar Khanim. "She was

a very strict woman. Whenever Vagif was practicing the piano,

she wouldn't let anybody disturb him. She would say: 'One day

Vagif will become famous, so don't disturb him.' She would even

come and take him away from the park and from the ball dances

if he needed to practice. Vagif was very obedient to his mother.

She was like fire."

Influence of Classical

Music

By the age of nine, Vagif was playing George Gershwin's "The

Man I Love," which he continued to perform throughout his

life. He went on to study the classics - Bach, Mozart, Beethoven,

Chopin, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, Mendelssohn and others. In fact,

so intense was his passion for music that it was impossible to

make him study subjects like algebra, physics, geometry and chemistry.

Vagif thought such studies were a waste of his time. He had little

interest in them. According to Rafig Guliyev, "Vagif didn't

like etudes and exercises. Of course, we were from the classical

school and were convinced that such exercises were absolutely

essential. But now 30 years later as I reflect back on Vagif's

life, I think he was probably right. Why did he need etudes?

He was at the piano all the time; he really didn't need to practice

those things.

Rafig recalls how one of Vagif's early teachers Rebecca Levine

used to complain how difficult some of the classical works were

for Vagif. "She had a hard time with him and told me about

it on several occasions," said Rafig. "He had difficulty

with Rachmaninoff's Concerto No. 2 and Beethoven's Sonata No.

11. But, you know, Vagif compensated for every weakness the minute

he sat down and started improvising jazz."

There's a story that Rauf Farhadov tells in his book about Vagif.

Once his piano teacher Georgi Sharoyev at the Azaf Zeynalli Music

School had assigned Rachmaninoff's Prelude in C-Sharp Minor.

As usual Vagif's mom had accompanied him to the lesson. Vagif

played the work beautifully from memory. But then Sharoyev observed,

"Zivar Khanim, he's playing C-Sharp Minor in the key of

C Minor."

This was something totally unacceptable to Sharoyev. Even though

Vagif had perfect pitch, it seems he hadn't realized that he

was playing it differently. So he played it again, this time

in C-Sharp Minor, amazing his teacher with his ability to transpose

with such ease and speed.

Later on, Vagif would always credit his versatility as a jazz

performer to his strong foundation in classical piano. In an

interview in 1979 with radio journalist (now Parliament member)

Rafael Huseinov, Vagif emphasized the value of classics as basic

preparation for the improvisational genre.

"If you want to go into jazz," Vagif had said, "you

have to enter through symphonic music. You can't become a professional

jazz performer without knowing symphonic music well. It's impossible.

You can't come to jazz without being able to play Tchaikovsky,

Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Mozart and Chopin. And when it comes to

Bach, he's absolutely essential. If a jazzman doesn't know Bach,

it's like 'his eyes have not been opened', as we say."

Vagif went on to describe the main difference between classical

music and jazz: "There are no scores in jazz. Only certain

rhythms, themes and compositions are written down. Then it's

up to the musician to improvise and show what he can do In jazz,

the composition is created and developed during the process of

actual playing. Everything begins from the moment that you sit

down at the piano and start to play."

Unlike classical music, when it came to learning jazz, Vagif

didn't have any specific teachers. He found his way independently,

experimenting and improvising entirely on his own. He learned

traditional jazz by listening to Charlie Parker and Bill Evans.

Vagif told Rafael Huseinov, "I love Bill Evans so much.

He's such a lyrical and unique pianist. Evans eats the keyboard."

Then there was Cecil Taylor, Michael Tyner, Ahmad Jamal and others.

Among the Soviet groups, he was particularly fond of Lukyanov's

Ensemble, Kozlov, and the Nikolai Levinski Ensemble.

Jazz on Short-Wave

Radio

Poet Vagif Samadoghlu recalls fond memories when he and Vagif

spent endless hours together, secretly listening to the short-wave

radio programs on VOA (Voice of America) and the BBC (British

Broadcasting Company), desperate to catch some lines of jazz.

Neither of them knew English. It was forbidden to listen to jazz,

so they would turn the radio down low so that no one could detect

them in adjacent apartments, just a thin wall away.

"After listening, we would try to reproduce the music on

the old piano in Vagif's apartment." Despite the fact that

both youth had studied music all their lives, it wasn't until

the mid-1950s that they ever actually laid eyes on any jazz scores.

"The only thing we could do was to listen every chance we

got, and then try to replicate the sounds that we heard,"

Samadoghlu reflects.

Nor did they have any means of copying the music that they heard.

Vinyl records, of course, did exist at the time. But personal

tape recorders and tape players were not widely available. Vagif's

teen years long preceded the age of videos, CDs and MP3 players.

On occasions, samples of some of the greatest Western jazz performers

would find their way into the Soviet Union, as they were very

popular. But mostly, budding musicians had to rely entirely on

memory and ear. According to those who knew Vagif well, he was

especially talented in these two aspects, endowed with a photographic

memory and an incredible ear for music.

Poet Vagif Samadoghlu tells how they used to pick up on jazz

motifs at the movies, too. "When we found a movie that had

jazz motifs, we would go watch that film over and over again,

sometimes 20-30 times. We would wait for the sections that had

jazz, then rush back home to try to reproduce them while they

were still fresh in our minds.

"You could always tell when an American spy was about to

appear in a Soviet movie. A few lines of jazz would signal his

entrance. The song, 'Sad Baby' in the film, 'The Fate of an American

Soldier,' always used to make us cry," Vagif recalls. After

World War II, they even had access to a few American films, some

of which had jazz on their soundtracks.

"Khrushchev's

Thaw"

After Stalin's death in March 1953, there was a backlash against

the harsh dictatorial practices that people had lived under for

the previous 30 years. Historians sometimes dub this period "Khrushchev's

Thaw" to designate how censorship was less severe. Some

of the prohibitions against jazz gradually lifted. But, naturally,

the public was cautious. It wasn't that the pubic didn't like

jazz. Rather, they felt that they needed to test which way the

political winds were blowing so as to be "politically correct".

The consequences of misjudging were too severe and so, the negative

attitude toward jazz lingered on. It was impossible to change

it overnight.

For example, once a Jazz Music Evening was scheduled for Music

School No. 1. Though no formal announcement had been made in

advance, the hall was packed. It was to be the first time that

Vagif would be performing his own compositions in public. But

at the very last minute, the concert was cancelled. The reason:

forbidden genre- jazz. It was one of the first of many disappointments

in his journey to become a jazz pianist.

Vagif graduated from Asaf Zeynalli Music College in 1963. Vasif

Babayev recalls those years: "There used to be parties in

the evenings at the universities where they played and danced

'rock-n-roll'. Vagif would go. When he appeared, everybody would

applaud and ask him to play something on the piano. Those years,

the authorities highly disapproved of 'rock-n-roll'-since it

originated in the West. Police would arrest anyone caught dancing

to it. So when Vagif would play, one student would stand guard

at the door to watch for university officials."

Idiosyncratic Style

When it came to performance technique, Vagif had his own idiosyncrasies.

"From the point of view of classical fingering," says

pianist Rafig Guliyev, "the anatomy of his hands was abnormal.

Everything was incorrect. He shouldn't have even been able to

play. Let me give you an example. When you play the scale of

E major, you have to position your hands a certain way. What

Vagif did is beyond description; it was something monstrous.

Vagif was extremely talented and brilliant; otherwise, it would

have been impossible for him to play like he did. It's impossible

to give a classical explanation to the nature of his playing

and describe his technique.

For example, with intervals of thirds, you're supposed to play

with your first four fingers. That's the classical way, but Vagif

would play them simultaneously with just one finger. I don't

want to give the impression that Vagif always played like a hurricane.

Not at all," Rafig continues. "His lyrical works, compositions

and improvisations were full of such stunning sensitivity and

such delicacy that they would make any classical player jealous.

Nobody taught him this. It was God-given."

In 1967, Vagif performed at the Tallinn Jazz Festival. Famous

world-known jazz players were there in the concert hall. Vagif

told Rafael Huseinov: "Before our trio performed, the Charles

Lloyd Quartet and Zbigniew Namislovski Quartet were on stage.

It was very difficult to impress the audience after their performances."

But Vagif went on to take the First Prize at the festival. "Even

those performers applauded us from their hearts. That concert

turned out to be one of the beautiful days of my life,"

he had recalled.

Javanshir recalls that at the end of each festival, there used

to be jam sessions. "Once Vagif proposed that they improvise

on a theme, for example, in E Miinor, but there was one restriction:

they had to play without touching the main key -"E".

It was an absurd idea to most musicians. Nobody believed it could

be done. But Vagif took up the challenge and started playing.

Others would stop him from time to time to check whether he really

had played the signature note or not. And they confirmed that

he really had not touched that note. It shows what kind of technical

level he had achieved."

Javanshir continues: "Once he was playing one of his pieces

called, 'Watch Out, Don't Make a Mistake' and he asked the rest

of us to guess what meter he was playing in. Nobody could identify

the beat but it turned out to be the simplest of rhythms: 4/4.

It's just that Vagif had just shifted the accent and that's what

had puzzled the audience. In classical music, they had already

started using such techniques. He knew classical music so well,

not just jazz."

One of the biggest disappointments in Vagif's life came when

he was not accepted into Baku's most prestigious music institution-the

Conservatory of Music (now Academy). You won't find it written

anywhere that the Rector rejected Vagif because he was too closely

identified with that troublesome genre, but Vagif's contemporaries

will tell you. And they'll tell you how disappointed he was not

to have been accepted into the Composers' Union, even though

everything he did was related to composing. Soviet bureaucrats

countered that Vagif did not qualify because "he had studied

Performance, not Composition" which was the criteria they

used for admittance.

Despite the fact that Vagif was appointed as pianist for the

Variety Orchestra of Azerbaijan State TV and piano soloist for

the Radio Committee of Azerbaijan following graduation from Azaf

Zeynalli music school, these other disappointments overshadowed

the situation, causing him to decide to leave for Tbilisi, Georgia.

There he would work three years, organize a musical group, and

meet Georgian Elsa Bandzeladze, whom he later married and with

whom he had his second daughter Aziza. It was popular songwriter

Rauf Hajiyev who begged Vagif to return to Azerbaijan. Baku beckoned

and Vagif returned.

Bucking the System

Knowing

Vagif's tenacity, Javanshir Guliyev observed: "Even if the

official line against jazz had not softened during the Soviet

times, I believe that Vagif still would never have changed his

position. Knowing

Vagif's tenacity, Javanshir Guliyev observed: "Even if the

official line against jazz had not softened during the Soviet

times, I believe that Vagif still would never have changed his

position.

Left: Desperate to catch

some lines of the jazz being broadcast on shortwave radio BBC

and VOA (Voice of America). During those days, jazz was forbidden

in the Soviet Union.

He was

passionate about jazz. He became consumed with this love and

obsession. It was even a mystery to him why he was so attracted

to it. But this music came from the heart and gave him the chance

to express his feelings."

He became addicted to jazz. He started experimenting with drugs

as well. Everybody knows, though few talk about it much. They

always insist that Vagif must be remembered for his brilliant

music and nothing else. His friends say that the fact that this

brilliant musician couldn't expose his inner world openly, gnawed

away at him. That's when he started drinking and getting involved

with drugs, they say.

Critics didn't help either. They offered contradictory opinions:

some sang his eulogies; others brutalized him. The pressure on

Vagif, both physically and psychologically was immense, according

to Javanshir. "It was difficult to commit yourself to jazz

under such pressure. Many other musicians gave up and took to

other popular forms of popular music-like the genre of Love Song."

Vagif ran into considerable opposition from the authorities.

Once the chairman of the TV Committee called him in and told

him that he would have to shave his big moustache because it

wasn't appropriate for TV. "I won't let you appear on TV

looking like that! We're building socialism. This kind of image

could hurt our reputation," the chairman insisted. And Vagif

shot back: "What about Marx? He had both a moustache and

a long beard, too." The chairman understood the irony of

his request and let it go. But Vagif was extremely upset and

disappointed. According to Javanshir, Vagif shared this story

among friends for years.

The TV people also complained about the big, ostentatious rings

he wore. They felt this showed lack of modesty and contradicted

the ideal image of the Soviet man. But Vagif wouldn't take them

off. "Vagif would never swallow criticism like this,"

observed Rafig. "He was rebellious by nature. He would not

accept their framework and prohibitions. He couldn't have cared

less about Communist rules and morals."

Vasif remembers that Vagif liked to dress like Elvis Presley,

wearing bell-bottom pants. Rafig Guliyev notes: "From outside

appearances, Vagif appeared to be such a peaceful lad. But when

it came to his work, he was a cruel taskmaster. He had such a

highly refined sense of perfection, and he demanded the same

dedication from those who worked with him. He didn't realize

that he was a genius and that others were mere ordinary mortals.

That led to confrontations and nervous breakdowns. Bad music

instruments simply 'killed him' and bad accompanists 'killed

him' too."

Travel Restrictions

There were other obstacles. Many had to do with restricting his

travel. The authorities wouldn't let him go out of the country.

Only once he went to the Soviet satellite state of Poland. Even

in that group, Eybat Mammadbeyli, Vagif's guitarist, recalls

how their group had to meet the other musicians in Moscow first

and present themselves as if they were part of the Moscow group.

Though they were capable of performing alone, they had to accompany

the other singers, too.

Aziza, Vagif's daughter, tells how her father used to receive

invitations to perform in Europe. "Once he was invited to

Finland to participate in a jazz festival. All the preparations

had been made and he had even boarded the plane. But just a few

minutes prior to departure, an official announced, 'Mr. Mustafazade.

Vagif Mustafazade, please return. Someone is waiting for you.'

So Vagif got up to see what was happening, and then they wouldn't

allow him back on the plane. It took off without him. It was

a ploy just to keep him from performing abroad. Simply, he was

a jazz player. There were many occasions like that," Aziza

recalls.

Pressures Pressures

"People like Vagif are heroes," says Javanshir. "They

struggled against their environs-against people who didn't understand

them. They had to be so strong just to keep doing their own work

and not betray their own artistic integrity."

Left: Waiting for a TV shoot.

Javanshir continues: "Censorship was everywhere. Music was

not exempt. Anything that was not in conformity with the Soviet

ideology was disapproved and banned. If, in the opinion of some

high official, a work was not in tune with the Soviet ideology,

the doors were slammed shut.

Alternatively, they would suggest that an artist create something

that would glorify the Soviet system. They would openly say:

'If you do so-and-so, your job will be much easier.' So musicians

and composers had to become very clever to accomplish their own

personal goals."

Eybat Mammadbeyli,

a member of the vocal group called "Sevil" that Vagif

created to perform on TV, recalls such compromises. Vagif was

severely restricted. "They didn't let us play jazz on TV

so we played Vagif's pieces after work. Unfortunately, our audience

was limited. Only after we resigned from the TV post were we

able to spend our time performing concerts and were less restricted."

"It was only because of Vagif's determination that he continued

with jazz," observed Javanshir. "He made the Azerbaijani

people so fortunate but it made his life so difficult. All these

pressures affected his relationships. Consequently, it began

to affect his health. There's no doubt that this immense stress

accelerated his death." Eybat elaborated, "In general,

he was a difficult person to communicate with. People were careful

when they spoke with him. You might say he was a person with

thorns, who demanded 100 percent sincerity and honesty from others,

as he was very honest himself, very sincere and appropriate in

his behavior towards others."

The Last Concert

Just prior to his death when he went to Tashkent (Uzbekistan)

to perform in 1979, Vagif passed Javanshir in the street and

stopped him. "We were experiencing such a cold spell in

Baku at the time," Javanshir recalls, "but Vagif held

me for 40 minutes there in the street, pouring out his heart

and complaining about his problems. He was extremely nervous.

You could even see the veins bulging in his neck. He complained

that his direction was fixed towards the West, but that the authorities

were sending him to the East. 'They never send me to Europe.

That's where they should send me, but instead they're sending

me to Tashkent. What am I supposed to do there?' Vagif had lamented."

Poet Vagif Samadoghlu, like other close friends, was not really

surprised when he learned that Vagif had collapsed and died from

heart complications after the performance in Tashkent on December

16th. "Somehow the tragedy came as no surprise to me. I

had somehow anticipated it," Samadoghlu admits. "Every

time I used to see him at the piano, I realized that he was taut

as a string. I knew that he would not be able to survive music

for very long."

Aziza recalls the last time she talked with her daddy-the day

before his death. It was four days prior to her 10th birthday

(December 19). "I had pleaded with him: 'When will you come

home? I want to see you tomorrow.' But he reminded me that he

had a concert the following day. 'But my darling, don't worry,

I'll be back, and we'll be together for Momma's Birthday (December

17)'. But it never happened."

Aziza talked more about the circumstances surrounding his death.

"It seems he had not been feeling well and the doctors had

cautioned him against playing. But he insisted. He gave a superb

concert despite the fact that not many people attended. The concert

had been scheduled to coincide with the annual Muslim religious

commemoration of Ashura-the day each year when traditionally

religious zealots fill the streets and flagellate themselves

to mark the commemoration of the death of Hussein, the third

Shiite Imam.

"Why?" asks Aziza, "Why did they schedule his

concert on that day? Clearly, the Soviet system wanted to antagonize

him. They were always doing things completely wrong. I can't

understand this old system. It broke the lives and hearts and

careers of so many people. In the end, my father died because

he was under so much stress. It really wasn't fair to him. They

had organized a concert for him on a day when they knew very

few people would come. They wanted to embarrass and shame him.

Music is not traditionally performed on that day in Muslim communities."

Three months later, on March 16, 1980, Vagif Samadoghlu helped

to organize a Memorial Night for Vagif at the Actors' House.

So many people came to pay tribute that they had to set up loudspeakers

in the lobby and the street. There just wasn't enough room in

the hall. A few days later VOA's Willis Connover devoted his

45-minute radio jazz program entirely to Vagif. Vasif Babayev,

one of his childhood playmates in the "Ichari Shahar"

notes: "Vagif lived 39 years under the Soviet regime. I

think he achieved more than was possible to have achieved at

that time."

"If Vagif were alive now, the whole world would know him.

Simply, he was born too soon," his friends insist. "So

many who had resisted Vagif during his life, embraced him after

his death. Only after he died did people understand what they

had lost," observes Javanshir.

According to Rauf Farhadov, Vagif seemed to sense that he was

going to die at an early age. He once told his wife Elsa, "I'll

go very soon. I don't have much time left." And she had

countered, "I won't let you. You can't do that." And

he had replied, "Well, when Death comes, He won't ask me

or my wife." On another occasion, Vagif had told her that

he sensed he would die while his hair was still thick and black,

not yet gray.

Heart trouble was not new to Vagif. He had had his first heart

attack in July 1969 at the incredibly early age of 29. It made

him always apprehensive about another attack. He had stopped

smoking and had tried to pay more attention to his diet.

Rafig Guliyev reflected, "Seeing that the people around

him wouldn't let him develop, wouldn't give him freedom-all these

things affected him. But the fact is: he loved life, he loved

his wife and his kids-Lala and Aziza, and he loved his friends.

And he infinitely loved this amazing jazz that he created-and

just that fact alone earns him the right to be idolized and not

just by Azerbaijanis."

Broken Dreams Broken Dreams

So many things were left undone; so many dreams unrealized.

Left: Accompanying a vocal

group.

Tours to Samarkand

(Uzbekistan) and Frunze (Kyrgyzstan) had to be canceled. He had

intended to produce another LP based on new arrangements of some

of the Love Songs composed by Tofig Guliyev (1918-2000) [See

earlier arrangements of Tofig's work on Volume 3].

Also in an interview with Rafael Huseinov shortly before that

last concert, Vagif mentioned that he wanted to work together

with his daughter Aziza and put together a concert. She was so

young at the time-not yet 10-but he had already realized her

potential in jazz.

In the radio interview, he shared his dreams with Rafael Huseinov

about creating a school in world jazz based on mugham. "I

have so many ideas. I have some compositions that I haven't finished.

All of them are based on the synthesis of jazz and mugham. Next

year, I'll work harder. I'll concentrate only on these pieces

and work seriously".

It never happened. And Vagif never lived to see the walls of

the Soviet Union come tumbling down. He would only have been

51 years old when Azerbaijan gained its independence in 1991

when so many doors would have opened to him.

His mother Zivar Khanim spent the last years of her life seeking

official permission to convert their apartment in the Old City

of Baku into a Home Museum to honor her son. She finally was

able to acquire two additional rooms to add to the space where

they had once lived. The Vagif Mustafazade Home Museum opened

on March 1, 1988, eight years after Vagif's death. Zivar Khanim

passed away eight years later in January 1996.

The Vagif Mustafazade Home Museum is a simple museum with photos

on the walls. Naturally, the piano draws the most attention,

as does the old wooden short-wave radio from which he and close

friends used to listen to that forbidden genre of jazz, coming

over the airwaves of BBC and VOA.

"It's amazing," said his poet friend Vagif, "that

the music that we strained to hear those 30-40 years ago was

able to penetrate the thick stubborn walls of totalitarianism

and that it still impacts how jazz is played in Azerbaijan today."

The Vagif Mustafazade Home Museum in Baku is open to the public.

It is located in Ichari Shahar on the street that has been named

after him: Vagif Mustafazade at Corner 4.

_____

Back to Index

AI 12.3

(Autumn 2004)

AI

Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics | AI Store | Contact

us

Other

Web sites created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|