|

Autumn 2005 (13.3)

Pages

64-69

Hajibeyov

Harsh Realities of Student Life

by

Uzeyir Hajibeyov

In

past issues of Azerbaijan International, we've often published

articles about the musical accomplishments of Uzeyir Hajibeyov

(1885-1948), who is regarded as the Father of Composed Music

in Azerbaijan. Hajibeyov's legacy is enormous. He is remembered

for so many "firsts" in Azerbaijan: first to synthesize

eastern and western music (blending Eastern folk melodies, modal

scales and traditional instruments with Western traditions of

chorus, opera and symphonic music), first to compose an opera

(Leyli and Majnun, 1907) and first to use harmony (1907). In

past issues of Azerbaijan International, we've often published

articles about the musical accomplishments of Uzeyir Hajibeyov

(1885-1948), who is regarded as the Father of Composed Music

in Azerbaijan. Hajibeyov's legacy is enormous. He is remembered

for so many "firsts" in Azerbaijan: first to synthesize

eastern and western music (blending Eastern folk melodies, modal

scales and traditional instruments with Western traditions of

chorus, opera and symphonic music), first to compose an opera

(Leyli and Majnun, 1907) and first to use harmony (1907).

Photo: Uzeyir Hajibeyov.

Hajibeyov was also the first composer to write a musical comedy

(Husband and Wife, 1910), first to introduce a woman on stage

(Shovkat Mammadova, 1912), first to write a national anthem (1918),

first to organize an orchestra for traditional instruments (1931),

first to hire foreign music teachers (1920s-1940s), first to

publish about music theory (The Principles of Azerbaijani Folk

Music, 1945), first in the entire Soviet Union, not just Azerbaijan

to receive honors as a composer (People's Artist of the USSR,

1941).

Back in 2001 when we were preparing the 7CD set of Hajibeyov's

major works, we interviewed many of Hajibeyov's former students.

Over and over again, they told us how this esteemed teacher was

extremely conscious of their economic situations. Often, he would

find an excuse to slip money to them unnoticed. Life was so difficult

during those years, with one national tragedy following the next:

the Bolshevik takeover in Baku (1920), Stalin's Purges (1930s

and 1940s), and World War II (beginning in 1941).

This same sensitivity

to the economic needs of students was mentioned by Ramazan Khalilov

(1901-1998), whom we interviewed in 1997 when he was Director

of the Uzeyir Hajibeyov Home Museum. This same sensitivity

to the economic needs of students was mentioned by Ramazan Khalilov

(1901-1998), whom we interviewed in 1997 when he was Director

of the Uzeyir Hajibeyov Home Museum.

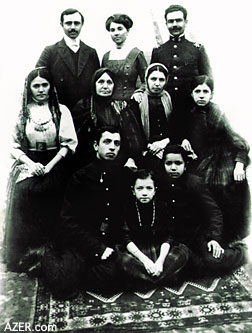

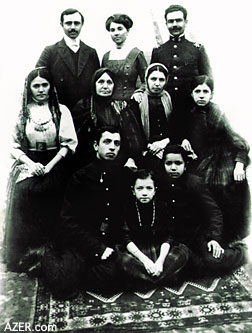

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov with his wife Maleyka

Teregulova. 1924. Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

Ramazan was 16 years younger than Hajibeyov but had known him

all his life since he was related to Maleyka, Uzeyir's wife.

Ramazan emphasized that Hajibeyov had lived very modestly but

was extremely generous, especially with young people studying

music. He recalled one of the trips to Moscow when Hajibeyov

went to attend the sessions of the Supreme Soviet [Hajibeyov

had been appointed a member in the 1940s].

"At that time,"

Ramazan told us, "there were about 15 Azerbaijani students

enrolled in universities there. Many of them came to visit Hajibeyov. "At that time,"

Ramazan told us, "there were about 15 Azerbaijani students

enrolled in universities there. Many of them came to visit Hajibeyov.

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov and his wife. Date

unknown. Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

He would take time to meet with each one privately and then he

would ask me to discretely pass each of them 500 rubles as they

left. On that trip alone, I distributed 7,500 rubles - the equivalent

of about $10,000 today."

"That evening we went out to dinner. Hajibeyov asked for

a menu, as he was craving caviar. But when he saw that 100 grams

would cost 3.5 rubles, he refused to order it: 'No, that's too

expensive,' he said."I got angry and told him: 'You've just

given away 7,500 rubles. And yet you won't even spend 3.5 rubles

on yourself! Why not?!'"

"Then he went

on to explain that while studying in Moscow and St. Petersburg,

he had had such a difficult life. 'There were times when I didn't

even have enough money to buy a crust of bread,' he admitted.

'I don't want these students to experience the desperation that

I did.' "Then he went

on to explain that while studying in Moscow and St. Petersburg,

he had had such a difficult life. 'There were times when I didn't

even have enough money to buy a crust of bread,' he admitted.

'I don't want these students to experience the desperation that

I did.'

Left: On holiday in Yessentuki. 1947 (one

year prior to Hajibeyov's death). Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

It is for this reason that we publish these letters here, penned

by the composer himself to his brother Jeyhun (1891-1962)

They provide a glimpse into Uzeyir's personal life and the economic

struggles that he had as a student. They show another important

dimension that shaped his life, and made him the great man who

is still remembered with such fondness nearly 60 years after

his death.

The trauma of those days was something Hajibeyov never forgot.

When he gained a position of authority himself and was economically

secure, he never forgot his own youth by reaching out to students

to shield them from the harsh realities that he had experienced.

These letters were originally published in Adabiyyat va Injasanat

(Literature and Art), November 4, 1988. No. 45 (2336). They were

prepared for publication by Ramazan Khalilov, who at the time

was Director of the Uzeyir Hajibeyov Home Museum. For the Azeri

(Latin script) version, search "money" at HAJIBEYOV.com.

Uzeyir wrote these two letters to his younger brother Jeyhun

(1891-1962) in 1912 while studying music in Moscow. Jeyhun was

in Baku. Uzeyir was 27 years old; Jeyhun, 21.

_____

Light of my eye [Nuri-dida]

Jeyhun!

From now on, I'll be writing every day or so about our situation

here. Don't lose these letters. Give them to Jamal for safekeeping,

in case I need them in the future.

Before we received our December money, we were in a bad situation

because we had not paid money to our landlord. So, every day

our landlord would knock on the door and walk in with his hands

in his pockets, demanding money. We would answer by saying that

probably later that day we would receive our funds. As we were

used to the landlord's regular visits, we didn't feel so pressured.

But one day I returned from the bazaar and went down to my music

class. Maleyka [my wife] was tutoring her cousin Amina and her

friend Zahida (these girls come to our place every day to study).

Suddenly, I saw that the landlord's ill-willed wife was poking

her head in and shouting, "When are you going to pay? You

say 'Tomorrow, tomorrow' to us every day!" Immediately,

I told the woman, "You have no right to demand money from

me in the presence of others."

I spoke harshly to

her and then came back in. I saw that Maleyka was confused about

what had happened in the presence of the girls, and she didn't

know how to change the subject. I was very upset, too, and felt

even worse. I spoke harshly to

her and then came back in. I saw that Maleyka was confused about

what had happened in the presence of the girls, and she didn't

know how to change the subject. I was very upset, too, and felt

even worse.

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov with his young bride

Maleyka Teregulova and other members of her family. 1910s. Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

If we had anyone here in Moscow, I would have borrowed money

from them and paid the landlord. And then we could have sworn

to our hearts' content and moved out. But, unfortunately, there

is no such a person in Moscow. I could count on Khudadad but

he is in Karabakh. There also is an Iranian - Mahammad Sadigh

Aliyev, an acquaintance from Baku. But I realized that he didn't

have any money either because I owed him one manat [Azeris used

to call Russian rubles, "manats" - the term used in

Azerbaijan].

He came to see me a few days ago. He didn't mention money, but

his face was unshaven. I realized he didn't have any money. I

didn't, either. He left in distress.

Anyway, Maleyka finished her class with the girls and said goodbye

to them. And then we sat in the room, looking at each other.

Maleyka wondered: "I don't know if the girls understood

what was going on or not." I would never have wanted our

relatives in Moscow to know our situation.

Then we decided to

go out - first to have some dinner and then to walk a little

to relax. Then we decided to

go out - first to have some dinner and then to walk a little

to relax.

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov. Courtesty: Hajibeyov

Home Museum.

It was 4 pm by the time

we reached the place where we could have dinner. The doorkeeper

Ivan took us upstairs. If we could have managed not to have to

eat, we would have done so because it has already been such a

long time since we paid Mariya Timofeyevna though she has never

demanded money from us.

But sometimes she would let

us know somehow that she herself was in need of money. That's

why we didn't enjoy our meals. Especially, after we ate, we didn't

know how to stop thinking about the situation.

Anyway, we rang the doorbell. The servant Sasha opened the door.

Mariya Timofeyevna's husband, a young man of 60 years old, was

running up and down the hallway like a kid. Somehow we ate our

dinner. The woman was expecting money from us. But when she realized

that we had none, she left for the bazaar.

We didn't want to go back home after dinner because we knew that

the landlord would demand money from us again. So we decided

to first go and find out from the doorman if the postman had

come. If he hadn't, then we would go to the Aliyevs to ask for

money. We walked towards the house and asked the doorkeeper but

nobody had come. We came back upset. We began to walk through

the city. But it's not good to walk through the city with no

money. Everything that you want is in front of your eyes, but

you have no money in your pocket to buy anything.

And then Moscow's beggars started hanging on us, begging for

money. If I told you that no beggars are more impudent than Moscow

beggars, I would not be exaggerating. They cling to you like

a leech. And, besides, there are so many of them. As luck would

have it, wherever there are beggars, they rush towards us as

soon as they see us. What a pathetic state of poverty and despair

we were in. On the one side were beggars, on the other were the

horse carriage drivers calling out, "Baron, let's go".

And then the flower vendors poked flowers in our faces, urging,

"Buy!" That made us feel even worse.

So, we walked a little and then decided to go find Aliyev and

borrow some money from him so that, at least, we could quiet

the landlord. I told Maleyka, "Let me take you home and

I'll go myself." So I took her home and at the door inquired

about the postman. But the doorkeeper said that nobody had come.

So I walked alone toward the street where Aliyev lived. On my

way I started thinking about how I was going to ask for money.

I felt so embarrassed and ashamed. Besides, I owed him money.

Anyway. My mind was filled with dark thoughts. To top it all

off, we had neither sugar nor bread left for breakfast. At that

moment, a black cat crossed the road. People were dressed in

black. Horses were black. Everything was black. I became a bit

frightened. "This is a bad omen," I told myself and

thought about returning. But then I calmed down.

The life of the great

composer Wagner came to mind. It comforted me to realize that

he - such a great man - suffered from even more poverty. At least

I could expect money from someone, some time. But that poor guy

had no one to help him while he was living in Paris. He and his

wife remained hungry. The life of the great

composer Wagner came to mind. It comforted me to realize that

he - such a great man - suffered from even more poverty. At least

I could expect money from someone, some time. But that poor guy

had no one to help him while he was living in Paris. He and his

wife remained hungry.

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov, 4, with his father.

In Shusha. 1889. Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

I continued my way towards Aliyev's place, but soon discovered

that he was not at home. I returned and sat down at one of the

tram stops to rest before heading home. Again, I asked the doorkeeper

about the postman. Again, nobody had come. I wondered whether

I should go home or not. Maleyka was waiting for the money. But

there was no money.

I thought about continuing to walk a while longer until she fell

asleep, as it was already 10 pm. But then I feared that maybe

the landlord might be fighting with Maleyka and swearing at her.

Just the thought made me rush home. I walked in and saw Maleyka

sitting there, upset. She became even more upset after she found

out what had happened. We quickly locked the door so that landlord

could not walk in on us.

As a result of these dark thoughts,

we both had bad dreams that disturbed our sleep and as a result,

we woke up late at 10 am the next morning. We were very upset

because we still had not received the money. Besides, we had

no sugar, no tea, no bread. It was the 11th. The next day would

be the last day of the month to pay the landlord, and then a

new month would begin. But we hadn't even paid the rent for the

previous month.

The doorbell rang. I thought maybe it might be the postman, bringing

money. But, instead it was a servant who said that someone wanted

to see us. As soon as I laid eyes on the man, I knew who he was.

He wanted money, too. He brought a note from the piano store.

It read: "Mr. Hajiyev, we are warning you again that the

time to pay for the piano expired last month. You haven't paid

us yet. If you don't pay today, we'll send someone to take the

piano away tomorrow."

I said fine and told the messenger goodbye. I saw that Maleyka

was worried that the landlord might return. This saddened me

because there I was not even able to comfort my wife. As a man,

I could not do anything to alleviate the situation without money.

With this thought, I went to see the landlord. I severely warned

him not to bother us until the 15th. I brought up the subject

of the rude behavior of his wife the day before and reprimanded

him. He saw that I was very angry. He complained for a while

and said that I should at least pay for one month. In the end,

he assured me that he would not bother us for the next five days.

I told Maleyka what happened.

Then we had a problem with tea. There had been times in the past

when we had not found bread for our breakfast tea. In that case,

we would sip our tea with sugar until dinnertime. But now we

didn't even have any sugar. We were finally able to scrape together

nine kopeks. Maleyka designated that half of them should go to

buy sugar and the rest to buy bread.

I thought maybe we should try to pawn some stuff. But then I

remembered that we had already pawned everything that we owned

- all of Maleyka's silver and gold jewelry, my violin, my coat,

Maleyka's summer coat. So, there was nothing left to pawn. At

that moment an idea crossed my mind. But I didn't tell Maleyka,

I simply left.

"You make the tea, I'm leaving," I told her. My idea

was to borrow some money from the doorman. I went and asked him:

"Didn't the postman bring any money?" "No,"

he replied. So then I made him an offer: "Give me three

manats. When I get money, I'll pay you two additional manats.

The doorman didn't say a word and pulled five manats out of his

pocket and said, "Give the change back later." I put

the money in my pocket. My eyes lit up.

With a happy heart, I went to the bazaar and bought sugar, tea,

bread, butter and a few newspapers. I returned home. Maleyka

had already prepared the samovar and was waiting. She was surprised

in seeing all the stuff that I had bought. But when she discovered

where I got the money, she got upset. Anyway, we had tea.

Then I remembered about Mirza, the son of Shamsi Asadullayev.

Mirza had been taking Turk [Azeri] classes from me. After a week

of lessons, he had told me that he wouldn't be able to study

for a few days. I asked him to call me when he needed me again.

Five-six days had passed. Mirza had not called. Today I remembered

and decided: "Why not go and check if Mirza is going to

continue his studies or not."

I walked to their office and asked the doorkeeper if I could

see Mirza. But I was told that Mirza had left for Baku quite

some time ago. I was surprised. I asked, "What about the

manager?" He asked me to wait a little while. Yusif bey

Vazirov came out. He was the manager, the son of Hasan bey from

Karabakh. Yusif greeted me and told me that Mirza had left 15

manats for me. "I didn't know your address to send it to

you."

I was so happy. I talked to Yusif bey for a while and asked him

to let me know if there were any job openings in their office.

He promised to do so. I took the 15 manats and went home so happy.

Maleyka was even happier. I gave the three manats back to the

doorkeeper and told him that I would return the remaining two

manats when my money arrived.

Then Maleyka said that her elder uncle had invited us to dinner

the next day. These days we are so very careful about spending

the money that we have in hand. I'll write more. Say hello and

give our prayers to the whole family.

Uzeyir

Moscow , 1912

__________

Uzeyir continues writing Jeyhun

about his poverty. No specific date is shown but it seems this

letter immediately follows the last one.

So,

we had 10 manats in hand. We had to buy a pair of rubbers (galoshes)

for Maleyka. By the way, speaking about "rubbers" reminds

me of a story. Let me tell you. So,

we had 10 manats in hand. We had to buy a pair of rubbers (galoshes)

for Maleyka. By the way, speaking about "rubbers" reminds

me of a story. Let me tell you.

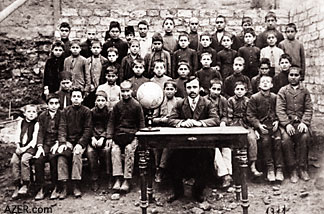

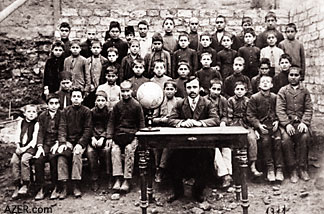

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov with students of Bibi

Heybat School where he taught math, Azeri and Russian. 1911.

Courtesty: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

It happened when Maleyka was still in Baku and I was alone in

Moscow. I was so lonely.

So, after quite a few letters

back and forth with her, I received a telegram saying that she

was leaving Baku.

That telegram made me very happy. I figured that she would arrive

in Moscow in two days. So on Tuesday, I awoke at 8 o'clock in

the morning and rushed out even without having tea. I went to

Kurski Station.

At the station I realized I only had six kopeks. I calmed myself

by saying, "Don't worry, 'Inshallah' [God willing], Maleyka

would be bringing money and then we would have enough for the

return fare." And so I waited in the station awhile and

then headed towards the platform. But the conductor stopped me

at the entrance and asked for a platform ticket. I didn't know

there was such a regulation in Moscow. Looks like there is.

So, what could I do? A platform ticket cost 10 kopeks. But I

had only six kopeks in my pocket. I thought maybe I could slip

through into the Third Class compartments of the train so I went

there and found a way to get onto the platform. A conductor,

standing at the door, said nothing.

That made me very happy. But when I rushed to the place where

train was supposed to arrive, another conductor stopped me and

demanded a ticket. It didn't take long to drop the six kopeks

into his pocket. I asked him to let me go. He did. Finally, the

train arrived, but Maleyka was not on it.

I searched inside

each passenger car but she wasn't there. I returned so upset.

There was another student looking for someone on that train,

too. He looked like an Armenian student from the Caucasus. Anyway,

I went out and asked the conductors whether there was another

station, which might have trains arriving from the Caucasus.

They mentioned Ryazanski Station. I searched inside

each passenger car but she wasn't there. I returned so upset.

There was another student looking for someone on that train,

too. He looked like an Armenian student from the Caucasus. Anyway,

I went out and asked the conductors whether there was another

station, which might have trains arriving from the Caucasus.

They mentioned Ryazanski Station.

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov. Courtesy: Hajibeyov

Home Museum.

I left the station and after asking directions from a policeman,

I found Ryazanski Station. I asked when the train from the Caucasus

would arrive. They said: "In an hour".

The same Armenian student was there. But, again, I needed a ticket

to get onto the platform. What could I do?

By that time, I had absolutely no money at all in my pocket.

Where and from whom could I borrow 10 kopeks to get onto the

platform? I had to do that because Maleyka would arrive and she

wouldn't know what to do. Where would she go if she didn't find

me? So, either I had to get money from somewhere, or somehow

I had to find a way to get on that platform. I headed toward

the platform.

There were two conductors and a policeman standing in front of

me. I stopped. I was looking at them when the policeman came

up and asked me not to block the way. So, I stepped back. I saw

that the Armenian student from the Caucasus had shown his ticket

and gone up on the platform. But I wasn't able to. I thought

for a while and suddenly an idea crossed my mind: I would sell

my galoshes.

Tatars, who for some reason Russians call "knyaz" [meaning

"prince" or "duke" in Russian], are famous

for buying old stuff here in Moscow. Sometimes it so happened

that these Tatars would stop me on the street and say, "If

you have any old stuff, we'll buy it." And so it was that

while living in a hotel there, I had sold some of my old clothes

to one of Tatars for six manats. But later I so much regretted

what I had done. If only I had kept those clothes, I could have

given them to someone to dye black. Then, at least I would have

had a couple of suits, whereas now I wear the same suit everywhere

and that tires everybody's eyes.

It's because I don't have a suit that's good enough that I haven't

been able to attend any theater or concert yet. For example,

when all of Moscow was rushing to a concert by the famous conductor

Artur Shalyapin, police riding horseback were pushing back the

people who wanted to get tickets. I lost my chance to buy a ticket

simply because I didn't have clothes that were good enough to

wear to the theater. If you don't have decent clothes, they won't

let you in.

One of my schoolmates plays bass fiddle at the Bolshoi Imperial

Theater and offered me a free pass. Also my piano teacher gave

me her ticket but I wasn't able to use it simply because I didn't

have a proper suit! But, back to the main point. So, I decided

to sell my galoshes. I walked down another street, back and forth,

to see if there might be a Tatar some place around.

As if God brought me luck, I saw a Tatar coming. As he was passing,

I stopped and asked, "Hey, are you a Tatar?" He replied,

"Thanks be to God, I'm Muslim. Are you Muslim, too?"

I told him, "Yes, I am."

After such a poetic introduction, I told him that I was selling

my galoshes. "Would you like to buy them?" Not the

least bit surprised, he said, "Well, OK, take them off.

Let me see them."

I took off my galoshes right there in the middle of the street.

He asked the price. I said, "One sum", meaning one

manat. He replied, "No, I'll pay half that!" If he

had known how desperate I was for 10 kopeks, he would not have

offered more.

But I hid my situation from him and started bargaining. But since

my galoshes were old ones that I had brought from Baku, I decided

not to argue much and sell them for half a manat. I took the

money and rushed to the station. I bought a platform ticket and

again found the Armenian student there. His Caucasian face caught

my attention. It brought to mind the Motherland. How I miss the

Caucasus. For the first time in my life, here in Moscow, I long

for the Motherland. I not only miss Baku and Karabakh, but I

miss all of the Caucasus.

That's why whenever I see anything here related to the Caucasus,

say, a Caucasian store or whatever, I stop and look at it. When

I see a Caucasian face, I focus on it.

Above: Members of the Commission of the Presidium

of the USSR Academy of Sciences together with the first full

members of the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan SSR (1945).

Courtesy: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

Actually, Moscow is not very

attractive. The streets are full of people, and it's hard to

move because of all the trams and horses and carriages. It's

so noisy here. Plus imagine all the church bells ringing from

the countless cathedrals; you wouldn't be surprised to find yourself

going deaf. A choir of beggars, and horse carriage drivers, street

vendors selling newspapers, apples and so on, shop owners, and

salesmen. They all trail after you, calling out, "Sir, sir,"

and begging you to buy their stuff.

Beggars differ so much from each other. Some are healthy, some

crawl on the ground, some have no legs, some have a bunch of

kids hanging around with them. It surprised me one day when I

heard a beggar speaking our Turkish [Azeri] from the Caucasus.

Also, one day, when I was sitting in my room, I heard a woman

in our courtyard telling some Russian women, "Gadayu, gadayu",

which in Russian means, "I tell fortunes."

But the Russian women didn't pay attention to her. Again she

called out "Gadayu" and then added, "Gadayu, a

jiyarin yansin, gadayu". ["A jiyarin yansin" in

Azeri is a curse that means literally something like, "May

your liver burn."]. I jumped to my feet, looked out the

window and saw that it was a beggar. Later I realized that there

were many beggars in Moscow from the Caucasus.

The only thing I love about Moscow are the crows. Their caws

remind me of valleys of Karabakh and of all the Caucasus. Anyway,

I went up to the student and asked, "Are you from the Caucasus?"

He replied, "Yes, I'm from Baku." And so we introduced

ourselves.

He was an Armenian. His last name was Hagnazaryan. On discovering

that my last name was Hajibeyov, he asked if I were related to

the composer of "Leyli and Majnun" [a mugham opera,

1907] and "O Olmasin, Bu Olsun" [If Not That One This

One", a music comedy written in 1911] who lived in Baku.

I said, "Yes, I am related." He asked, "What is

your relation?" I told him, "It's me." The Armenian

guy got so happy. He immediately started singing one of my melodies.

Anyway, I found out that he had been expecting grapes from the

Caucasus. The train arrived. But Maleyka wasn't on it. Instead

of Maleyka, a conductor by the name of Goldschmit from Jeleznovodsk

approached me. On seeing him, it reminded me of the wonderful

days we had spent in Jeleznovodsk. The grapes for the Armenian

guy didn't arrive either. So we both got on a tram and returned

to the city. I invited him to my place for tea. Anyway, I'll

write you about Maleyka's arrival later.

Back to the original subject that I was writing about. So, the

heels on Maleyka's galoshes were worn out, and one of them had

a hole in it. That's why whenever Maleyka went out some place,

she would hide them in a corner where no one could see them.

When it was time to leave, she would rush to get them and put

them on herself before the servants could bring them and place

them in front of her.

But when the servant in our apartment saw the hole in Maleyka's

galoshes, she suggested that we repair them. She said that there

were many shoe repairmen. But instead of mending the old ones,

we decided to go to "murmurliz" to buy new ones. There,

for two manats, ten kopeks, we bought a pair of galoshes. Then

we decided to reclaim Maleyka's earrings from the pawnshop, where

we had put them in hock for two manats.

Otherwise, without the earrings, the holes in Maleyka's ears

would knit back together. Unfortunately, we decided against it,

fearing that the money wouldn't come. Then we would have nothing

at all to live on. We had known before what it was like not to

have any money. So, we bought the galoshes and went out to eat.

We hardly ate anything and returned back home.

On seeing us, the doorkeeper said that the postman had come twice

to bring the money. I asked how much he had brought. He said,

"150 manats". I can't describe how happy Maleyka and

I were. Now we could be rid of our landlord's unhappy face (Maria

Timofeyevna).

We went to bed. Early in the morning, the servant awakened us.

She said that the postman had brought the money. So I got it.

Then we dressed and had tea. Suddenly, the landlord walked in

and said, "Congratulations." Right away I took the

bill from her and handed her a 100-manat note. I asked her to

take the money that we owed her, and return with the change.

Being a Jew, she took the money and asked if she could borrow

10 manats.

Above: Full members of the Academy of Sciences

of Azerbaijan (1945).

Left to right, seated: Samid Vurghun, I.G.Esman, Hajibeyov, A.A.Alizade,

M.A.Mirgasimov, I.I.Shirokogorov, A.A.Grossgeim, M.A.Topchubashev.

Standing: Y.G.Mammadaliyev, M.A.Ibrahimov, Sh.A.Azizbeyov, G.N.

Husseinov, S.A.Dadashev, M.A.Usseinov.

Courtesy: Hajibeyov Home Museum.

I realized my mistake and regretted

having given her the 100-manat note. I refused to lend her any

money and explained that I needed it myself. She said, "OK"

and replied that she would bring back the change right away.

She left and soon came back, only to tell me that she had "borrowed"

5 manats anyway. She promised to return it to us the next day.

Unwillingly, I consented. She charged us 52 manats for two months'

rent, borrowed five manats, and returned the rest.

I put the money in my pocket. Maleyka and I went to her older

uncle's place. Maleyka has three uncles here: Kheyraddin, Mahammad,

Dovlatyar. They all have wives: Latifa, Marjub and Zuleykha.

I'll write you about them later.

From the money that we received, we paid 57 manats to the landlord,

40 manats to the place where we eat, 12 manats for the piano,

2 manats to our doorkeeper, one manat to the servant, half a

manat to the doorkeeper of the house where we eat, one and a

half manats to the servant there, half a manat to the postman,

10 manats to pay off some debts and buy some small stuff.

So that left us with only 25 manats left. I had to pay 35 manats

to the school, which I attended because up until then I had only

paid 110 manats, whereas you have to pay 75 manats each semester.

I had a conflict with the director of the school. I'll write

you about that later. But I couldn't pay him anything from 25

manats.

That's why I missed a few classes. After that, holidays began.

Maleyka and I decided not to eat at the same place where we had

been eating before, as we couldn't afford it. In spite of the

fact that the meals were good and we were quite satisfied with

them. What could we do? We couldn't afford to pay 40 manats for

meals. So, we let them know that we wouldn't be eating there

any more. Well, now we have to think of where to go to eat.

Uzeyir

Moscow 1912

_______

For more articles about Uzeyir

Hajibeyov, search at AZER.com

or visit HAJIBEYOV.com

- the Web site dedicated to the legacy of Uzeyir Hajibeyov, created

by Azerbaijan International magazine. The librettos of all of

his major works are available in Azeri (Latin script) with translations

in English.

Back to Index AI 13.3 (Autumn

2005)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|