|

Winter 2005 (13.4)

Pages

76-77

Mukhtar Avsharov

Beating

the Prison System

A Stone's Throw to Freedom

by

Reza Avshar, his son

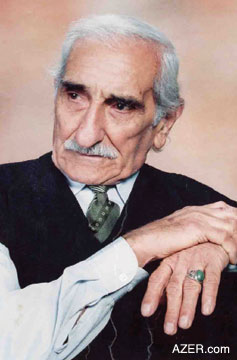

Mukhtar Avsharov (1914-2004), was recognized

as a "People's Artist of Azerbaijan" for his work in

drama. He was extremely active throughout his life and continued

performing on stage until he was 90 years old. Even the pretense

that the government gave for arresting him back in 1937 can be

traced to his love for the theater. Mukhtar Avsharov (1914-2004), was recognized

as a "People's Artist of Azerbaijan" for his work in

drama. He was extremely active throughout his life and continued

performing on stage until he was 90 years old. Even the pretense

that the government gave for arresting him back in 1937 can be

traced to his love for the theater.

As was true for the majority of civilians who were arrested,

Mukhtar was charged with an unbelievably flimsy excuse - in his

case, protesting the renaming of the drama theater in the city

of Ganja where he lived.

Mukhtar saw no relationship with drama and Lavrenty Beria for

whom they wanted to name the theater. Beria was deputy head of

the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) - the ministry,

which oversaw the state security and police forces. In other

words, he was the top official who was in charge of administering

the notorious prison camps.

Of all the 20 or more oral histories that we collected in preparation

for this issue, Mukhtar's story is the only one in which a prisoner

actually managed to gain the attention the highest authorities

and succeed in getting his case dismissed and, subsequently,

released earlier than scheduled. Mukhtar was convinced that if

he could only pass a message to Stalin about the unreasonableness

of his case, he would walk free. After several attempts to reach

Moscow, he succeeded. His is an amazing story, told here nearly

70 years later by his son, Reza, who would never have been born

had his father, who was extremely ill by that time, not succeeded

in getting released early.

It wasn't until father returned from labor camp that he settled

down and started a family. Back in 1939 when he was arrested,

he had only recently married. We weren't born then. Years of

separation between my father and mother followed until he returned

home.

As children, we learned that father had been repressed during

Stalin's era, but we didn't know the details. Back then, most

parents didn't tell such things to their children. They were

frightened that - someday, somehow - such knowledge might jeopardize

the lives of those whom they loved most. Some casual slip of

the tongue - a seemingly innocent remark - could easily endanger

someone's life. And so, parents generally refrained from telling

their own children the deepest secrets and concerns of their

lives.

Besides,

as young children, we wouldn't have understood such things, and

for father, it was very painful to talk about them. Besides,

as young children, we wouldn't have understood such things, and

for father, it was very painful to talk about them.

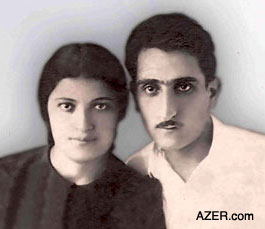

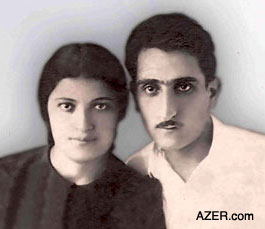

Left: Mukhtar and his wife Fatma in 1946

after he had come back from exile. Photo: Courtesy of the family

of Mukhtar Avsharov.

It seems that he eventually decided to tell me for fear I

might run into problems myself, given that, through no fault

of my own, I could be identified as "a son of an Enemy of

the People." Such things often happened to children whose

parents had been repressed. For example, they often were denied

entrance into the university or overlooked for a job in their

field of expertise.

But my father did open up and tell me about his situation. It

happened in 1971 - 35 years ago. I had just completed my military

service. It was my first night home.

We happened to be watching television about some prisoners, and

my father commented: "That's nothing. I've seen all that,

plus more - with my own eyes."

That's when I started asking questions. It's no wonder, we stayed

up the whole night talking about it. It was so unusual for my

father to talk so intimately like that.

Publicly, he never spoke about those things - not until 20 years

later when Azerbaijan had gained its independence from the USSR

(1991).

My father was born in Yerevan (Armenia). He later moved to Ganja

(northwestern Azerbaijan) where he worked as a metal craftsman

for the railroad. He loved literature, history, art and culture.

In his youth, he had been selected to attend a cultural camp

in Moscow for three months. After returning home, he started

getting involved with the drama theater in Ganja.

As a young person, my father used to talk with his friends about

things that bothered him; for example, when the Soviets changed

the name of his city Ganja. That name could be traced back at

least to the 12th century. The Russians had changed it to Elizavetpol

(1813), and then Stalin went on to rename it Kirovabad (1935),

after Sergey Kirov, the Russian who had been instrumental in

bringing the Red Army to Azerbaijan in 1920 to take over the

newly formed Azerbaijani independent government.

My father also was concerned about the Russification or Sovetization

that was going on throughout the country. People were starting

to use the Russian language in public. Later, many families even

started to use Russian at home, as it had become the prestigious

language all over the Soviet Union. You couldn't advance in your

career without being fluent in it. My father was against this

as well. He felt that people were losing their national identity.

They were forgetting Azeri. And then the Soviets started naming

the streets after Communist "heroes". But the people,

in general, didn't yet identify with those heroes. They didn't

like the new government replacing Azerbaijani names with Russian

or Communist names.

|

|

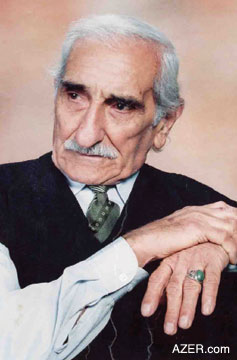

Above Left: Mukhtar, 25, in 1939, the year of

his arrest. Right: Mukhtar in 2002 at age 88. Photos:

Courtesy of the family of Mukhtar Avsharov

My father's troubles began after the officials had announced

that Ganja's Drama Theater would be named after Lavrenty Beria.

This person had no ties to theater or drama. He was the head

of the NKVD (National Committee of Internal Affairs and forerunner

of the KGB) and administered the vast prison system - the Gulag

network that gradually became so widespread that several thousand

camps spanned the breadth of the USSR across 12 time zones. Basically,

Beria became Stalin's executioner.

So my father - the patriotic, young actor that he was - stood

up in a public gathering and voiced his concern. He couldn't

see any relationship between Beria and the drama theater. Of

course, his arguments went unheeded and the theater took on Beria's

name. My father claims that all his troubles started from there.

This all happened in December 1939. My father was 25 years old.

He had a close friend - also an actor [Reza preferred not to

mention his name]. Later on, this "friend" was honored

as a "People's Artist" and became quite famous. He

has since passed away.

My father trusted this guy so they used to talk together a lot.

My father would joke with him and ask how it was that his friend

always dressed better and enjoyed better food, given the fact

that they both were actors, both recently married, and both,

supposedly, earning the same salary.

His friend didn't appreciate the joke. It wouldn't be long before

my father understood why. This "friend" turned out

to be an NKVD agent. It seems there came a time when my father's

friend had not provided enough "news" to the agency.

They demanded information. After all, they were paying him.

So, one day my father, this agent, and another actor, were sitting

around chatting at the "chaykhana" (tea-house), and

father started expressing his concerns, especially in regard

to the Russification that was taking place. He was convinced

that people were forgetting their own culture, their language

and history. He felt Azerbaijan was developing into a Russian

colony; Russia's power was felt everywhere. And, so that day,

my father's "friend", indeed, had something to report.

On a cold day in December 1939 at 2:00 o'clock in the morning,

a "Black Raven" [the type of car that the NKVD used

to arrest people] stopped in front of my father's place. They

took him straight from his bed. That first night in prison, they

beat and tortured him. My father told me how they would make

the prisoners put their hands on a door frame and then some big

guy would lean against it and break their fingers. After that,

my father's fingers were crippled for life. They also broke his

teeth, telling him it was his punishment for speaking against

Stalin, Beria and Soviet authorities.

Later they brought his "friend" in as a witness. My

father was shocked when he realized who had betrayed him. Then

they brought in the other guy who had been with them at the tea

- house.

But nobody told my father's family what was going on. Where was

he? Was he alive? Was he well? Was he being tortured? Had there

been a trial? His brother and sister, along with some other relatives,

tried to get answers from the authorities at the NKVD, but they

learned nothing. They were even told not to bother coming back,

unless they wanted to get into trouble themselves.

My father had only been married for three months prior to his

arrest. Like so many other families faced with the same circumstances,

my grandmother (my father's mother) told the new bride that she

could leave and marry someone else because she was still young

and beautiful. After all, no one knew if her husband were still

alive or not. But the woman who would become my mother chose

not to leave and remarry. She had faith that her husband was

still alive, and that one day he would return.

It turned out that father did have a "trial" of sorts

- if you want to call it that. There was no lawyer to defend

him. Just three judges - the typical arrangement that came to

be known as a "troika". In the end, he was sentenced

to 10 years of hard labor - a typical sentence at that time.

Already, he had spent seven months in the basement of NKVD building,

which was notorious for its brutality and torture.

My father was then transferred to Baku. Back in the late 1930s

there was no airport here. It didn't exist. So they used prisoners

as free labor to clear and level the land, and build the runway.

It wasn't long afterwards that World War II began.

My father

used to talk about the conditions, which they endured. My father

used to talk about the conditions, which they endured.

Left: Mukhtar performing in a TV play in

2000. Photo: Courtesy of the family of Mukhtar Avsharov.

It seemed unusual to

him that they would separate political prisoners from the criminals

and even treat such hooligans better. As for the political prisoners,

it was normal for them to work 12 hours a day - intensive, hard

labor, carrying heavy loads all day long.

Then there was the poor food. They mostly were served a kind

of soup, a weak broth despite how hard they labored.

There were thousands of prisoners in his camp. My father used

to tell how every morning they would carry out corpses from the

barracks. They called them "dokhodyaga" ("goners"

- someone dead or about to die).

They couldn't bear the conditions and simply died from starvation.

The authorities would arrange for a big ditch to be dug and the

bodies would be buried there en masse. Probably, if someone were

to carry out excavations at the airport today, they would discover

skeletons from those times.

In the camp with my father was another prisoner called Alexandrov.

They soon became good friends. Alexandrov had worked at the Soviet

Embassy in Tokyo. Something must have happened and they had brought

him back to the Soviet Union as a political prisoner. You see,

people were brought to these camps from all over the Soviet Union-even

foreigners, whom they captured as prisoners of war.

Alexandrov told my father that it was very unfair that he had

been arrested for complaining about a name. He advised him to

try to reach Stalin himself. They worked out a scheme so my father

could send a letter from the camp. It went like this. My father

gathered 30 rubles and found a little scrap of paper on which

he wrote: "Dear person who finds this note: Please send

this letter to Moscow and keep the money. It's yours." Inside

was a letter explaining my father's situation. Then he wrapped

the letter and money around a rock and tossed it over the prison

fence.

Father could have been in serious trouble had anyone seen him

do it. He had to be very secretive. It turned out that he carried

out that identical plan on three occasions. He was determined.

It wasn't easy to collect so much money in the prison camp, but

his friends helped him.

Finally, it seems that someone found the note on the third try

and did send it on to Moscow. That must have happened around

1944. He had already been imprisoned for five years.

Now it turned out that about that time there was another prisoner

who had finished his prison sentence. My father asked him to

go to Ganja, and tell his family that he was still alive and

where he was being kept. Father promised his family would award

him with a gift for bearing such good news. This is an Azerbaijani

tradition.

So the friend went and found my father's family. As a result,

my uncle came and found my father. Fortunately, it happened just

in time.

Years later, my uncle told me what it was like when he first

saw my father in the camp. My uncle had brought a container of

food and other necessities and gone and talked to the director

of camp, who, in turn, ordered the guards to bring my father.

My uncle remembers a long corridor. He saw the door open down

at the end, and a rather obese man came out, escorted between

two men with guns. My uncle didn't pay much attention to them

because he had in mind that his brother would be thin. He had

always been a slim fellow.

But then the prisoner addressed my uncle: "Manaf, don't

you recognize me?"

My uncle looked up and recognized the facial features of his

brother whose body was swollen from hunger. My uncle was stunned.

They cried and hugged each other. The truth is: had my uncle

arrived even a few days later, father would have been dead.

So my uncle passed his gold watch to the director and promised

to return in three or four days with some money (bribes, of course).

He urged the director to take special care of his brother and

not let him die. Because of that, they sent him to a medical

unit for treatment. Although my uncle had brought food for my

father, it was impossible for him to eat; he was so ill.

So, my uncle started visiting my father in the labor camp on

a regular basis and bringing food and medicine. At home, the

family sold everything to buy medicine and food and to bribe

the director. The good news came from Moscow that my father would

be released - obviously, as a result of the letter that he had

tossed over the fence. He was still four years shy of completing

his ten-year sentence. When the order for his release came at

the camp, the officials had him beaten up again, trying to discover

how he could have possibly got that letter out of the camp. But

my father wouldn't tell them.

|

"Are children

guilty of the evil deeds committed by their parents?

Why should children be held responsible for them?

--Reza Avshar whose father

refused to retaliate against the agent

who falsely accused him and caused him be sentenced to 10 years

of hard labor

|

The camp director was a Russian:

Korovin, by name. He was so surprised when he heard about the

letter. He ordered my father to confess how he had done it. Again,

father refused to tell.

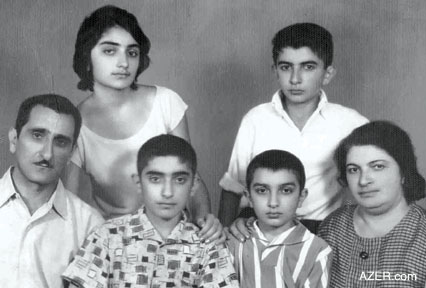

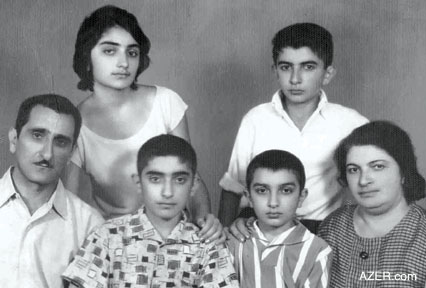

Above: The Mukhtar Avsharov Family. Top

(1960): Sitting (left to right): Mukhtar, Rauf and Nuri, and

wife Fatma. Standing: Sevar and Reza. Photo: Courtesy of the

family of Mukhtar Avsharov.

Then there were more complications. It happened around that time

that two criminals succeeded in escaping from the camp. The director

told my father that until those two criminals were found, he

could not be released. After all, maybe he was the one who had

assisted their escape. One of the escapees was a Russian and

managed somehow to return there. The other was Azeri who made

the blunder of returning home, only to find the NKVD already

waiting for him. So the Azeri was brought back to the camp. But

since the Azeri said my father had nothing to do with his escape,

finally, my father was released.

That was February 1945 - six years after he had been arrested.

Although father was very ill and weak, he returned home to Ganja.

Arriving there alone, by himself, at dawn, he recognized the

broken down fence around their home, and saw his mother inside,

sweeping the courtyard. He decided not to approach her immediately.

He was afraid that she might have a heart attack if the news

came too abruptly. After all, she was quite old and sick herself.

Eventually, he recognized a neighbor passing by and greeted him.

He asked him to take the news to his mother that her son was

alive and that he had seen him in Baku. Again, father promised

that his family would award him with a gift for bringing such

good news.

So, the neighbor did as he was instructed, adding that Mukhtar

would be coming home soon one of these days. When his mother

heard the news, she dropped her broom. She was so happy.

Above: Muktar (sitting). Standing: Abbas Abbasov

(Deputy Prime Minister), son Reza and his wife Irada, granddaughter

Jamila, daughter Sevar, and Jamila's husband Ulvi. Photo: Courtesy

of the family of Mukhtar Avsharov.

Soon my father himself entered the house and the whole family

gathered around to drink tea together. But two hours had not

even passed before one of those dreaded NKVD cars stopped in

front of their house. Again, they took my father to NKVD office.

There they made him sign papers that he would never seek revenge

against the actor who had betrayed him. Nor would he tell anyone

about the circumstances that led to his arrest. The officials

didn't want anyone to know who their agent was. Father signed

and, in truth, he really did not tell anyone. He was afraid of

the possible repercussions.

They also told him that he could no longer be associated with

the theater any more since it was an ideological center and connected

with culture. He could only get a job as a laborer. Usually,

they didn't even allow political prisoners to return to live

in large cities. They made them move to the countryside and outer

regions. However even though Ganja was a rather large city they

agreed to let him stay there since he was young and his family

was there. So, after agreeing to all of these conditions, they

released father.

As you can imagine, it took quite a while for my father to recover

both physically and emotionally from being imprisoned. Later,

he got a job as a worker in a mill, carrying heavy loads.

After Stalin died in 1953, the political situation throughout

the country became somewhat more relaxed, and my father again

decided to apply to work in the theater. This time they accepted

him. Of course, he had a lot of catching up to do as an actor.

All those years away from the theater had affected his professional

career.

Time passed. And the NKVD agent, who had betrayed my father,

became ill with cancer. It seems he sensed that he would soon

die and he asked my father to come to visit him. That was in

1961 or 1962. My father decided to go. I can't imagine what it

was like for him to come face to face with the person who had

brought him so much suffering. My father says that agent looked

him in the eyes and said, "I'm sorry." It seems he

wanted to try to clear his conscience before he passed away.

When I later learned that my father had gone there, it made me

realize what a great human being he was. I'm sure that I couldn't

have done that. I wouldn't have been able to forgive all those

lost years in prison and labor camps. But never once did I ever

hear my father say anything bad about that man.

Stalin brought misery to hundreds of millions of innocent people.

Tens of millions of them died. When most people think back on

Stalin, they consider him to be a very complex person. They say

he accomplished things both bad and good. In my opinion, the

only positive thing that can be said about Stalin is that he

won the war against Fascism. That's all.

I think my father was right not to name those people who informed

on him. That generation has already passed away. Those times

are gone. In fact, my sister even became close friends with the

children of that agent. My father didn't object to that. They

used to live across the street from us. Are children guilty of

the evil deeds committed by their parents? Children cannot be

held responsible for them. Those horrible deeds were not their

fault.

Of course Stalin used to repress anybody who was in anyway associated

with the person that his regime had branded as an "Enemy

of the People" - sons, daughters, fathers, mothers, husbands,

wives, cousins, uncles, aunts, friends. Anybody. No generation

was immune from his reach. But that didn't make it right. I'm

convinced that children should not carry the stain of their parents'

wrong-doings all of their lives.

You have to consider the situation back then. If, for example,

four people were gathered together, you could be sure that at

least one of them was an agent. So, if Azerbaijan had a population

back then of four or five million, perhaps, one million of them

were turning others in.

Today, I think that if the general public knew which individuals

were responsible for the horrors that their loved ones suffered,

they would take it upon themselves to revenge those wrongs and

those deaths. And society would suffer irreparably. It would

be so deadly.

Somehow, we managed to survive that dreadful era. We shouldn't

go back and cause that evil and death all over again.

Reza Avshar, son of the late

Mukhtar Avsharov, shared the memories of his father. Reza is

an artist. His works can be seen on AZgallery.org.

Back to Index AI 13.4 (Winter

2005)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|